Out of the Blue

Jeopardy!

My daily dose of after-dinner angst

By Deborah Salomon

When people of a certain age finish comparing aches and pains, medications and grandchildren, the conversation turns to Jeopardy! — hereafter known as J!. Odd, since few seniors appear as contestants. I mean, they don’t compare notes on 2 Broke Girls after eating the local diner’s Early Bird Special.

That’s because this backward quiz show, which debuted in 1964 (! indeed), serves as a barometer. Make that thermometer, since nobody’s sure what a barometer measures. And if they are, they can’t define barometric pressure.

Can you?

Anyway . . . I have learned much about myself and others from J!, things unrelated to the answers. First, deal with suave Alex Trebeck, who wears great suits and looks amazing for 77. His only fault seems to be a language affectation, mostly French, where he exaggerates pronunciation, meaning “See, I know what I’m talking about and you don’t.”

He does, actually, since his mother was French-Canadian. I won’t excoriate his know-it-all attitude. Not hard, Alex, when answers are on the card you’re holding, with the foreign words spelled phonetically.

As for the exclamation mark, the producers offer no explanation except emphasis — and to raise the question among people who notice, because all don’t.

Then, “It’s the category, stupid!” Well-rounded, I’m not. Gimme food, literature, vocabulary, body parts, famous people dead or over 50, architecture, art, nursery rhymes and I’ll pop out answers, right or wrong, abetted by three stupefying (except for the toga party) years of high school Latin, since Latin is the root of everything.

Do kids take Latin anymore?

But pop culture, pop music, movies and TV shows I thought nobody watched, American history, science (chemistry and biology didn’t stick), geography, math (got As, don’t remember a thing) put me under a dunce cap, in the corner, now considered child abuse. The occasional miracle happens: The answer to an obscure clue just bursts from my mouth. I can’t place where I heard or learned it. I call it “stray matter,” instead of gray matter. Right now, I can’t even remember an example — not a good sign.

In fact, I’m much more likely to score in Final Jeopardy because I know, after years of watching, to seek the clue within the clue. Hello, Captain Obvious!

Now, the real fun. Or, what happens when you watch alongside someone from a similar memory pool. The air crackles with unfriendly competition. Your reputation is on the line. And then a particle floating through the parietal lobe short-circuits the synapses, causing you to freeze with the answer just beyond tongue tip. This erodes confidence, may ruin a friendship.

During these sessions I hear, “I do much better when I watch alone.” (Don’t we all?)

How about, “I’d get ’em all on multiple choice.” (Better than nothing.)

Remember, contestants study, practice with coaches. These hot shots know Indonesian inland waterways and English kings’ Roman numerals like I know, well, enough stuff to get the occasional thrill, especially during the junior championships.

Last, I’ll confess a wicked pleasure: Spectrum airs the same episode of “Jeopardy!” at 7 and 7:30 p.m., on different channels. Watch the first, round up regulars for the repeat and show ’em who’s boss. (!!)

Otherwise, don’t sweat the results. Win or lose, brain games keep mature minds sharp. And, eventually the big-money answer to Final Jeopardy will be Arthur Godfrey, ipso facto, Happy Rockefeller, carpe diem, vox populi, ad hoc, Daisy Mae or moratorium. PS

Deborah Salomon is a staff writer for PineStraw and The Pilot. She may be reached at debsalomon@nc.rr.com.

Mom, Inc.

Look Out Below!

A day of schussing and moguls

By Renee Phile

We’d talked about going the past few winters. It’s one of those activities that seems fun but overwhelming. In theory, appealing, but the logistics are scary. Well, we decided this was the year. We were visiting my grandparents in the mountains — Boone, North Carolina. He woke me up early.

“How much longer? When can we go?”

“David, we can’t go till one.”

“Can we go early?”

“It doesn’t even open until one.”

The time ticked slowly (for David) and around 1 p.m., David and I — in our three layers of clothing, armed with gloves and hats and those knitted ski masks bank robbers wear in the movies — piled into my car. Up the mountain we drove. My grandparents drove their car, too, to get us checked in. This was their idea, after all.

We peered over the houses on the mountain. It was snowy, steep, and gorgeous. Like in a jigsaw puzzle or calendar. Scary, too. The wind was ferocious. Halfway up the mountain, the traffic stopped, a foreshadowing of what was to come. We inched our way to the lodge. To say it was packed would be. . . let’s just say it looked like an Uber convention. It was 1/2 off lift tickets day, and the world loves a bargain. The whole world. All the times I spent at Walmart nearly having a panic attack from too many people dimmed by comparison. There were three lines that wrapped around halls and swirled around walls. Finding the end of one was the goal. Anxiety built.

Some people were filling out forms, and my grandpa left the line to find some for us. These are the forms where you absolve the entire world of responsibility in the event you crush every bone in your body. When Grandpa stepped into the madness, I wondered if I would ever see him again. He returned with paperwork for David and me, with an extra set for the red-haired kid in front of us, who already had his skis. It was at this point my grandma said, “We are going to go home. Call me before you leave here.” Part of me envied them as they left. It was the part that screamed, “For godsakes, don’t leave me here!” on the inside. We chatted with our line mates. It turned out the red-headed kid was from a town close to Southern Pines.

“Have you skied before?” I asked, already knowing the answer.

“Yes, a lot, but this is the first time I have been here. You?”

“I skied when I was his age,” I said, pointing to David. “This is his first time. We are going to need a lesson.”

“Nahhh, we don’t need a lesson,” David chimed in, his phone out as he YouTubed How to Ski. “It’s easy, Mom.” I could remember nothing of the basics of skiing besides gravity. The red-haired kid said, “I can show you a few things; you probably don’t need a lesson.” I was unconvinced but agreed.

Time passed. Another 30 minutes, then another. David became grouchy, and I reminded him over and over that he was the one who really wanted to come. We helped each other out of our coats as sweat dripped down our faces. Finally, it was time to step up to the counter. A rush filled me. Almost two hours of waiting had ended.

We paid for our lift tickets, skis, helmets and a locker, and the adventure began.

The actual ski part could be summed up like. . . well, how about I share with you some texts that I found, yes found, on my phone later that night. Caren is my best friend from high school, and I had sent her a picture of David and me standing in the forever line. I must have left my phone somewhere and forgotten about it for a while.

Caren: How was your Christmas?

David: Good, this is David (smiley face)

Caren: Hey David! Looks like y’all went skiing. Did you have fun?

David: Yes we did, my mom fell every few feet though.

Caren: Haha! That’s always fun (smiley face)

David: Not for the people in her path.

Caren: (2 smiley faces)

David: She just about killed this one guy and took out about 6 others.

Caren: (smiley face) Maybe she’d be better on a snowboard. I did awful on skis.

David: Maybe you should go with us next time.

So, I read through these messages that had been exchanged on my phone. While there is some truth in these texts, they are exaggerated, of course, and David failed to mention that he, too, nearly “killed one guy and took out about 6 others.” At one point he was just lying in the middle of the slope while others, trying not to use his body as a ski jump, zoomed by. (Don’t tell him I told you . . . )

Neither of us learned how to stop without falling or even move around without going straight down the hill. Both of us came home with bruises, hurt pride, but lots of laughter.

Next time — and there will be a next time — we won’t pay attention to any red-haired kids. PS

Renee Phile loves being a mom, even if it doesn’t show at certain moments.

Story Of A House

Starting Over

Living the “love thy neighbors” life

By Deborah Salomon

Photographs by John Gessner

Fresh. Stylish. Practical. Now.

Fresh. Stylish. Practical. Now.

When newlyweds Jennifer and Eric Ritchie renovated and furnished a charmingly unremarkable home on a Pinehurst No. 6 cul-de-sac, they brought absolutely nothing from their previous marriages or homes: no furniture, no memorabilia.

“Not a dish, not even a towel,” Jennifer says. “We know where everything came from and it’s ours.”

They did bring plenty of ideas and the experience Jennifer gained as a Realtor specializing in military relocations. They weren’t planning to occupy the house for long; it would be a buy-and-flip investment. But as the project progressed they fell in love not only with the house but also the neighbors.

“That’s why we stayed,” she explains. Socializing began the day they moved in, when two children arrived bearing cake. Since then, life is a never-ending block party, with holidays celebrated communally. “We visit our families beforehand so we can be here.” Gates were inserted into fences enabling rescue pups Max and Molly to romp with next-door dogs. Their yard became activity central when, to an in-ground pool (raised to 4 1/2 feet uniform depth, for safety) the Ritchies added a stone fireplace beyond the spacious deck. “It’s cinder block and stone, not a kit,” Eric announces proudly. If a ball game is on, no problem. Each outdoor area has a TV. Professional mosquito spraying and two patio heaters encourage year-round comfort.

“We love to entertain,” Jennifer says. More likely 30 friends and colleagues for a barbecue than intimate dinners although with this  couple’s enthusiasm, anything goes.

couple’s enthusiasm, anything goes.

Both Jenn and Eric have military connections. Her father was Army, Eric is a Navy veteran who served in Desert Storm. Neither brings a homestead imprint. She grew up on several bases, including Fort Bragg, and in Ohio. Eric describes his boyhood home in Albemarle as a plain N.C. ranch with dark paneling and a pool. Eric works with tactical communications equipment for the military. Jenn’s experience in real estate honed her eye. This house was on the market for only a day before they grabbed it for over asking price. She could see beyond pink and gold bathrooms and a wet bar in the living room. This house, built in 1996 was in good shape, well-located and priced attractively. The layout suited them: a master bedroom wing with a second bedroom for a joint office, since they both work from home. A guest bedroom on the opposite side for visiting family, including Eric’s 23-year-old son. They removed a Jacuzzi tub from the master bathroom to make room for an oversize shower and installed a floor resembling distressed planks. White paneled kitchen cabinets were retained, granite countertops and a tile backsplash added. Now the room pops, even without the customary Wolf stove and SubZero refrigerator.

A breakfast nook overlooking the pool became a sitting room. Jenn chose pale neutrals — dusty sea green and sandy beige for the walls, to set off darker brown furnishings.

Crown moldings? Jenn shakes her head.

Crown moldings? Jenn shakes her head.

At just under 2,000 square feet spaciousness is created by light streaming through tall paned windows with eyebrow arches.

“Our (previous) house was much bigger but we didn’t need all that space,” Jenn says.

An hour after the closing, workmen were pulling up carpet to install a charcoal grayish engineered wood flooring that not only sets the contemporary tone but is practical with dogs and a pool.

The entire renovation took only 28 days.

So far, so good. Now add personality from a couple unfettered by convention: After planning a wedding at the Fair Barn Jenn and Eric decided to run away to Hawaii and marry on the beach, minus family and friends — which explains the string of numbers and symbols painted on a narrow board hanging from the dining room wall.

“We collect co-ordinates from everywhere we go; these are from Hawaii, where we got married,” Jenn explains. Another strip represents their Pinehurst home.

As for overall motif, the Ritchies chose farmhouse — a popular genre promoted by online furnishing sites — which means angular lines, simple materials, peeling paint and rough, distressed woods. Over the dining room table hangs a light fixture resembling a weathered tulip-shaped metal bucket of mysterious origin.

“I didn’t want it to look like anyone else’s” Eric says.The kitchen pantry door — once half of a French pair — was cut down to fit, with defects left intact. Their king-sized bed

employs a larger door as headboard. Jennifer painted the living room coffee table turquoise and Eric fashioned office shelf supports from plumbing pipe.

“I show Eric what I see on Pinterest and he does it.”

Because everything is new or freshly rejuvenated — and purchased in a swoop — the appearance could be a Crate & Barrel, Wayfair or Pottery Barn layout. Heavens, no. “Everything’s local,” Jennifer says — some new, some repurposed, many unique pieces from décor shops in Aberdeen where they shopped together on weekends. Growlers (“our ‘thing’”) collected from North Carolina breweries and travels march across a kitchen soffit shelf.

Which leaves the couple’s final stamp — framed signage, slogans, sayings and messages hanging from walls, embroidered on pillows, everywhere. Some are large, in bold print, like ANTIQUES over the guest room sleigh bed. Others are site-appropriate: Happiness is Homemade, in the kitchen. Laundry, over the utility room. Flea Market, Best Day Ever, Eric and Jenn 9-2-16 (wedding) and, sweetly, All You Need is Love. American flag representations appear more than once. Photos of pottery and elephants remind them of a recent trip to Thailand. A giant “R” stands by the front door.

Might this be the only home in Pinehurst fielding but one antique — a plain oak sideboard in the dining room, from Eric’s great-aunt?

Might this be the only home in Pinehurst fielding but one antique — a plain oak sideboard in the dining room, from Eric’s great-aunt?

This summer they will tackle the exterior . . . maybe a new front door. Jenn wants to paint the brick and put up cedar shutters. She will add shrubs to the crape myrtle and white birch on the half-acre lot.

Obviously, the Tufts family did not build enough Old Town “cottages” to satisfy today’s affluent retiree/renovators. Neither did architect Aymar Embry design sufficient pied-à®-terre in Weymouth to accommodate history buffs. Therefore the great majority of people, many military-connected, who settle in the area need something else. Eric and Jennifer Ritchie found it on a tiny cul-de-sac in a large development of houses priced moderate to more. Their finished product, perfectly “staged,” would sell in a flash, at a substantial profit. Nothing doing.

“If it weren’t for the friendship with neighbors, we wouldn’t still be here,” Eric says.

“We all help each other,” Jenn adds. “You can’t replace that.” PS

Golftown Journal

The Homecoming

Putting guru David Orr brings his fantastic fundamentals back to Pine Needles

By Lee Pace

On a December afternoon, David Orr peers around the building and the wall space at the Pine Needles Golf Learning Center at the far end of the resort’s practice range. There is an enlarged version of a vintage American Golfer magazine cover featuring Peggy Kirk Bell, who owned the resort for some 60 years prior to her death in 2016. There is a 1920s photo of the par-3 third hole at Pine Needles. There are assorted other charts and images tied to the business of golf instruction.

Finally, Orr finds an uncluttered spot with no decorations or adornments.

“Here,” he says. “They can sign their names right here.”

Over a decade of teaching putting and the short game to more than 60 Tour professionals from his previous headquarters at Campbell University in Buies Creek, Orr established a tradition of having his clients sign and date a wall in his putting studio.

Justin Rose has been there. So have Hunter Mahan, Cheyenne Woods, Suzanne Pettersen, Edoardo Molinari and Trevor Immelman.

“It started when I was working with some guys who were pretty much unknown, were trying to get established on the Web.com Tour or European and Asian tours,” Orr says. “I told them, ‘I want your autograph before you become famous.’ Then I started working with guys further up the World Rankings — Justin and Hunter, guys like that. The wall kind of represents my development as a coach. It’s pretty cool.”

Orr’s career as a swing coach and putting guru has essentially came full circle in the fall of 2017 as he relocated his Flatstick Academy teaching and coaching business back to Pine Needles, where he was on the instruction staff from 2000-04 and learned the business under the tutelage of Mrs. Bell and a staff that included Pat McGowan, a PGA Tour regular from 1978-91, and Chip King, who’s gone on to become director of golf at Grandfather Golf & Country Club.

“This is a homecoming for me,” Orr says. “I think of Peggy every day. Every day. I stand on the range and look around and say, ‘Wow, every brick, every blade of grass — they’re here because of her.’ She built the dream. You cannot replace her. But it’s an honor to be back.”

Kelly Miller, the CEO of the company that owns and operates Pine Needles and its sister resort, Mid Pines, plays frequently in top amateur tournaments and last summer needed some help with his golf swing. He invited Orr to drive down from Buies Creek and look at his swing — and talk a little business. Miller had been following Orr on Facebook and on Orr’s Flatstick Academy website and saw references to golfers traveling to Buies Creek for a lesson.

“I thought, why not have those people come to Pine Needles if David is operating from here?” Miller says.

He took a 15-minute full-swing lesson from Orr, who got Miller’s swing plane adjusted from laid-off to on-line, and threw out the idea. Miller proposed that Orr could still have the freedom to teach at Campbell, work with his professional clients and travel as he does around the world to speak at instruction conferences.

But the rest of the time, he would use Pine Needles’ facilities for his individual and group lessons focusing on putting, chipping, pitching and bunker play. He would also operate multi-day short-game schools and consult with the Pine Needles staff in running the resort’s well-known golf instruction programs.

“This is a unique opportunity to get someone of David’s skill and reputation to come here,” Miller says. “David is certainly one of the top two or three putting instructors in the United States. He’ll bring some energy and an exciting niche to what we’re already doing.”

Orr says his experience working at the top level of the PGA Tour has given him a sense of accomplishment that makes the move back to Pine Needles a comfortable one at this juncture of his career. He helped Rose with his putting and short game, and then watched as Rose won the 2013 U.S. Open. A year later, he followed as Rose went head-to-head against another of his clients, Mahan, in the Ryder Cup.

“I don’t have to prove myself any longer,” Orr says. “Early on, I was like a salmon swimming upstream. Now it’s cool to step on a practice tee on tour and think, ‘I don’t have to prove anything.’ I have so much fun working with amateur golfers and juniors. I can help some younger guys and borrow from my experiences the last 10 years.”

Orr is a native of upstate New York, played college golf at Bridgewater in Virginia, and then graduated in 1991 from Oswego State in New York with a degree in political science. That summer he was working at a club in Syracuse and was impressed by the wad of hundred-dollar bills the head pro was making on the lesson tee. The idea of becoming a golf instructor lingered in the back of his mind the next several years as he played the mini-tours, and Orr eventually moved to Raleigh and worked at Cheviot Hills and North Ridge Country Club.

“I was still playing some on the mini-tour in the mid-90s when I was giving lessons at Cheviot Hills,” he says. “I won one mini-tour event but was making more teaching than playing.”

Orr joined Mrs. Bell’s teaching staff at Pine Needles in 2000 and learned over four years that there was more to teaching than simply applying the highly technical dictums from two of the enduring influences on his own swing — PGA Tour player Mac O’Grady and Homer Kelley’s book, The Golfing Machine.

“I got to Pine Needles with a lot of science in my head and learned from Peggy the art of teaching,” Orr says. “‘How-to’ instruction doesn’t work all that well. The brilliant ‘ah-ha moment’ with Peg was her drumming it into my head that you need to get students to do something in order to learn it. I can remember, David, get them out there doing it. That was a huge turning point. I learned to make instruction palatable so that people could understand it and improve.”

Orr left in 2004 to take classes in the Professional Golf Management program at Campbell and obtain his Class A-6 PGA status, which he did in 2007. He joined the Campbell faculty and became director of instruction for the PGM program, and during the late 2000s began doing extensive research into putting — from technique to equipment to green reading.

One of his motivations to crack the putting code was the fact that his own putting ability had been, in his word, “terrible” over his competitive career.

“I was terrible for many of the same reasons everyone else is,” he says. “You miss a couple short ones and you get down on yourself and all of a sudden you’re afraid. I used to avoid practicing putting. I changed putters and grips and changed my stroke. I’d go take lessons. The more I tried, the worse I got. That’s how I came to a turning point. I did the research and started teaching putting.”

One of the significant developments for him was learning the SAM PuttLab system, which uses 3-D technology to analyze some 28 parameters of the putting stroke and displays the results in easy to understand graphic reports. He and Dr. Rob Neal of Golf BioDynamics pioneered research on the working of the hands, wrists, forearms and upper arms in the putting stroke. That research became the basis for Neal’s GDB 3-D System, which in the last decade has taken putting stroke and full-swing analysis to new technical levels.

“My teaching method is based on research, not on theory,” Orr says. “I offer very little ‘how-to’ information. One of the things I learned from using SAM was, ‘Never guess what you can measure.’ That’s one of my policies: I don’t guess.”

Orr evaluates each golfer and offers suggestions and direction based on analysis of three key skills to holing a putt: Can a player read a green? How good are they adjusting to speeds of greens? And are they able to start the ball on-line?

“Those are the three skills — read, speed and line,” says Orr. “With each element, we take the guesswork out. We measure it. Then we take what you have and make it the best it can be. There is no perfect putting technique — except your own.”

Orr turns 50 in 2018 and says he’s at the perfect place at Pine Needles to write the next chapter of his teaching career. Indeed, there’s a blank space of wall in his new putting lab just awaiting some signatures. PS

Chapel Hill-based golf writer Lee Pace has been writing “Golftown Journal” since 2008.

The Omnivorous Reader

The Last Ballad

Wiley Cash creates a model for other writers

By D.G. Martin

Readers of this magazine have come to know and admire Wiley Cash as a regular contributor of poignant essays about his family, his work, and his writing.

In the October issue, he gave us a very personal report about the origins of his latest novel, The Last Ballad. He told us that for the past five years he had been “living in a 1929 world of cotton mill shacks, country clubs, segregated railroad cars, and labor organizers with communist sympathies. Everything I know about the craft of writing and the history, culture and politics of America, especially the American South, has gone into this novel.”

Now that the book is out and Cash’s promotional book tour is drawing to an end, it is a good time to take another look at this remarkable story of blended fiction and important history.

When Cash takes us back to 1929 Gaston County’s textile mill country, he forces us to confront real and uncomfortable facts about the brutal conditions workers faced. All the while Cash uses his storytelling gifts to create a moving tale about a real person, textile worker and activist, Ella May Wiggins.

On the frame of this real character, Cash builds a moving story that puts readers in Wiggins’ shoes as she walks the 2 miles every evening from her hovel in Stumptown to American Textile Mill No. 2 in Gaston County’s Bessemer City, works all night in the dirt and dust and clacking noise, and then walks back to tend to the children she has left alone the entire night.

Cash follows her decision to support the strike at Loray Mills, where her ballad singing at worker rallies mobilized audiences more than the speeches of union leaders. He relates how her actions also provoked negative responses from union opponents that led to her death.

In the book’s powerful fourth chapter, Cash compresses the conversion of Ella May from oppressed textile worker to inspirational union hero into one evening. As she rides in the back of a truck from Bessemer City to a pro-strike rally at the Loray Mill in Gastonia, she tells Sophia, a union organizer, about her family’s struggles, the death of her beloved son, and “the weight of her children and their lives upon her heart.”

“Hot damn,” Sophia says. “And you sing too?

“Hell, girl, we hit the jackpot with you. You might be the one we’ve been looking for.”

That evening in Gastonia, in the shadow of the “colossus of the Loray Mill . . . its six stories of red brick illuminated by what seemed to be hundreds of enormous windows that cast an otherworldly pall over the night,” Ella May tells her story to the rally’s crowd and sings a song from her mountain youth that she adapted on the spot.

She began,

“We leave our home in the morning,

We kiss our children good-bye.

While we slave for the bosses,

Our children scream and cry.”

And after several more verses of struggle and woe, she concluded,

“But understand, dear workers,

Our union they do fear,

Let’s stand together, workers

And have a union here.”

When it was over, “people cheered, whistled and pointed, called her name and chanted union slogans. Flashbulbs popped and illuminated ghostly white faces as if lightning had threaded itself through the audience.”

By the end of the evening and the conclusion of the fourth chapter, Ella May has the makings of a legend and a target of the anti-union forces that will bring about her early death.

In the book’s other chapters, Cash introduces us to people who shaped Ella May’s life: her no-good husband John, her no-good boyfriend Charlie, the Goldberg brothers who ran the mill where she worked, her African-American co-worker and neighbor Violet, the union strike leaders, a 12-year-old worker who loses half his hand when it gets caught in the mill’s machinery, and Wiggin’s children as they struggle through hunger and illness.

We also meet an African-American railroad porter, Hampton Haywood, a communist union organizer. Ella May makes an unlikely friendship with Katherine, the wife of mill owner Richard McAdams. Katherine persuades her husband to sneak Hampton out of town to save him from a racist and anti-union lynch mob, risking Richard’s place in the elite social order — and his life.

The picture Cash paints is an ugly one, showing conditions of Wiggins and her fellow workers to be only a step or two away from serfdom and slavery.

Education for the workers or their children was a pipe dream, as Wiggins explained to U.S. Senator Lee Overman, when the union sent her to Washington to tell the union story. Overman had told a striker she should be in school.

“Let me tell you something,” Wiggins shouted at Overman. “I can’t even send my own children to school. They ain’t got decent enough clothes to wear and I can’t afford to buy them none. I make nine dollars a week, and I work all night and leave them shut up in the house all by themselves. I had one of them sick this winter and I had to leave her there just coughing and crying.”

In his first two best-selling novels, A Land More Kind Than Home and This Dark Road to Mercy, Cash had wide freedom to develop compelling stories and fashion endings that would surprise and satisfy his readers. But he lost this freedom with The Last Ballad. Historical fiction binds its authors to certain facts. There can be no surprise ending. Cash’s readers know from the first page that Ella May is going to be killed.

In Cash’s case, however, the genre does not restrict his great gifts in character development or in developing rich subplots that give his readers a satisfying literary experience. As a bonus they come away with a deeper comprehension of Ella May’s experiences and those of the people on all sides of the Loray labor conflict.

In his October article for this magazine, Cash, who grew up in Gastonia, explained what made writing about Wiggins a difficult task. “How could I possibly put words to the tragedies in her life and compress them on the page in a way that allowed readers to glean some semblance of her struggle?”

Recently he told me, “I wanted to write a novel that was not only true to the facts, but I wanted almost more importantly to write a novel that felt true to the experience as I understood it. When I was writing this novel I was perfectly aware that these are real events. And the facts are all there. The facts in this novel, are indisputable. And I felt like, by getting the facts right, it allowed me a scaffolding to let the characters come alive.”

So how did Cash do?

I agree with Charlotte Observer writer Dannye Romine Powell, who called The Last Ballad Cash’s “finest” novel, one that she suspects “will serve as a model for any writer who wants to transform fact into fiction.”

In creating this model for other writers of historical fiction, Cash met his challenge of putting into words Wiggins’ tragic life and the oppressive times in which she lived.

And those words and the story they tell confirm Cash’s place in the pantheon of North Carolina’s great writers. PS

D.G. Martin hosts North Carolina Bookwatch, which airs Sundays at noon and Thursdays at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV.

Hometown

A Policeman’s Life

Duty and kindness serving the citizens of a small town

By Bill Fields

At a gathering of my Pinecrest classmates a few months ago, men and women closing in on 60 like a restless Corvette, one of them pulled me aside early in the evening to tell me a story. During a stressful year that included some challenges, listening to his recollection turned out to be a highlight of 2017.

In the late 1970s, not long after we had graduated from high school, my friend had gotten in his car after a few too many drinks at a work party. Realizing his condition, he parked in an empty lot in West End. As my friend tried to sleep it off, my father, then a deputy sheriff working the second shift, came upon the car to check it out. Startled and scared, the driver roared away quickly. Blue lights on, Dad soon followed, and my friend was pulled over, more anxious than he had been a couple of minutes earlier.

As my friend, an African-American, was recalling the encounter, it seemed like a scenario that these days all too often unfolds into disaster. But his tale didn’t have a bad ending. When my father walked up to the offending vehicle and pointed his flashlight at the driver, he recognized who was behind the wheel and let him explain what had taken place. There was no overreaction, no show of force, no ticket, no crisis. After a warning from my father and a promise from my friend to go straight home, that was it.

An anecdote isn’t everything, but hearing it sure made my night.

Dad came to law enforcement late, when he was in his late 40s, and it became a belated career after a series of jobs following World War II — farmer, gas station operator, clerk and factory foreman. He worked as a third-shift radio dispatcher in Southern Pines, then was hired as a patrolman in Aberdeen. He also had two stints as a Moore County deputy and, during the latter, when he was a warrant server, he got to drive the squad car home.

Whether wearing Aberdeen blue or Moore County khaki, Dad looked sharp in his uniform, probably cocking his hat a few degrees more toward jaunty than specified. Some of his fellow officers went for low-maintenance plastic-exterior work shoes, but my father’s black ankle boots were leather that he kept beautifully shined with a sturdy brush that seemed older than he was.

I was fascinated by the shorthand of the radio communications, the 10 codes. On the occasional snow-day morning when I was riding shotgun, there was nothing better than driving into the Town and Country shopping center and hearing Dad 10-20 at Cecil’s Steak House for breakfast. A few years later, riding through Aberdeen in my girlfriend’s orange MG en route from Chapel Hill on a sneaky trip to the beach, I knew Dad was on duty and got to the town limits hoping he was out of service having a meal.

Being a cop — although Dad hated that word — in Moore County back then was a lot more Mayberry than Manhattan. Directing traffic after July 4th fireworks at Aberdeen Lake could have been as dicey as things got. I am not aware that he ever had to draw his .38 caliber service revolver. (He let me fire it once, at a tin can out in the country north of Southern Pines, and that was enough.)

Dad was involved in one high-speed pursuit, when a car raced north at 100 miles per hour on Highway 1 until it took the Morganton Road exit and crashed at Memorial Field. Investigating bad car wrecks was the toughest part of the job. Once, on a day when Dad got home after dealing with a serious accident, he quickly corrected me when I mentioned that I wished I had been able to see it.

He was an imperfect man, but being a policeman brought out his best. On a cool, dreary day in 1980, through a rain-dappled rear window of a Powell town car on the way to Pinelawn Memorial Park, I was reminded that others thought so too. Many officers from multiple area departments lined our route and blocked intersections, traffic not the reason for their presence. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.

Bookshelf

February Books

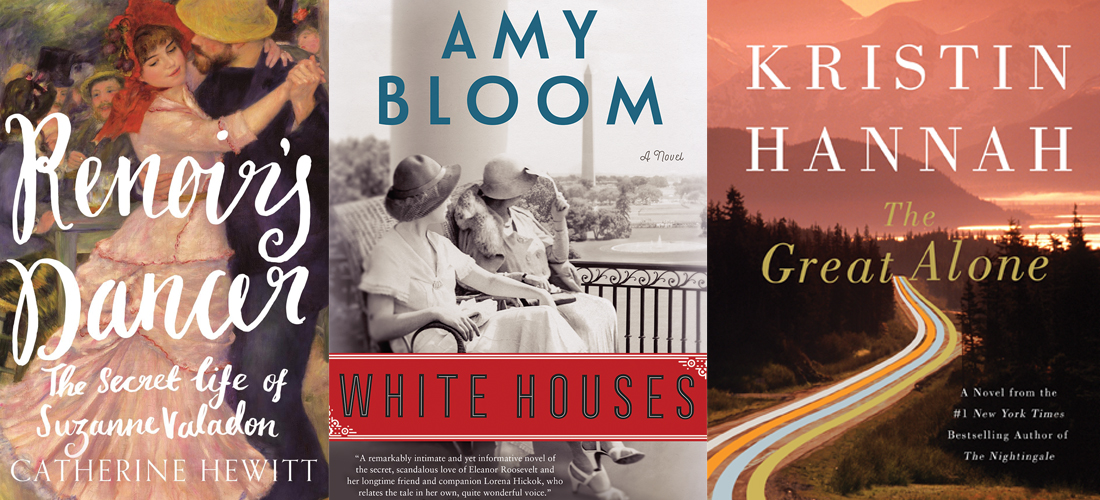

FICTION

The Great Alone, by Kristin Hannah

The author of The Nightingale returns with a story of a family of three, Ernt, Cora and Leni, who move to the remote Alaskan wilderness in the 1970s. After years as a prisoner of war, Ernt is restless, tormented and given to rages. Leni is precocious and befriends a young, sweet boy whose family is on a collision course with her own.

Only Child, by Rhiannon Navin

Hiding in a coat closet, Zach Taylor hears gunshots echoing through his school as a gunman takes 19 lives, irrevocably changing the close-knit community. While Zach’s mother goes on a quest for justice against the young gunman’s parents, Zach loses himself in a world of books and art, becoming determined to help the adults around him rediscover the love and healing compassion in their lives.

White Houses, by Amy Bloom

Beginning with Lorena Hickok’s childhood and following her through Eleanor Roosevelt’s death, Bloom’s fiction brings a slice of history to life in this lively and heartbreaking biographical novel about the long-term relationship of the two women.

The Hush, by John Hart

Returning to the world of Hart’s The Last Child, it’s been 10 years since the events that changed Johnny Merrimon’s life and rocked his hometown to the core. Though Johnny has fought to maintain his privacy, books have been written of his exploits. Living alone in the wilderness outside town, Johnny’s only connection to normal life is his boyhood friend, Jack. The Hush is more than an exploration of friendship, persistence and forgotten power. It takes the reader to unexpected places, and reminds us why Hart, after five consecutive New York Times best-sellers, warrants comparison to luminaries like Pat Conroy, Cormac McCarthy and Scott Turow.

An American Marriage, by Tayari Jones

A masterpiece of storytelling, An American Marriage is a stirring love story and a profoundly insightful look into the souls of three people who must reckon with the past while moving forward — with hope and pain — into the future. Jones, the author of Silver Sparrow, writes a brilliant book that is both a joy to read and thought-provoking.

Promise, by Minrose Gwin

In the aftermath of a tornado that rips through Tupelo, Mississippi, at the height of the Great Depression, two women — one black, one white; one a great-grandmother, the other a teenager — fight for their families’ survival in this powerful novel. A story of loss, hope, despair, grit, courage and race, Promise reminds us of the transformative power of confronting our most troubled relations with one another.

NONFICTION

The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South, by John T. Edge

The director of the Southern Foodways Alliance writes a people’s history that reveals how the region came to be at the forefront of American culinary culture, and the way issues of race shaped Southern cuisine over the last six decades.

Everything You Love Will Burn: Inside the Rebirth of White Nationalism in America, by Vegas Tenold

Embedded among three of America’s most ideologically extreme white nationalist groups for the last six years, journalist Vegas Tenold has watched these groups move from a disorganized counterculture into the mainstream. Tenold offers a terrifying, sobering look inside these newly empowered movements, taking readers to the dark, paranoid underbelly of America.

The Leading Brain: Neuroscience Hacks to Work Smarter, Better, Happier, by Friederike Fabritius and Hans W. Hagemann

Now in paperback, this book by a neuropsychologist and a leadership expert applies science-based strategies to achieve peak performance. Examples such as how to learn and retain information more efficiently, improving complex decision-making and cultivating trust and building strong teams are highlighted.

Berlin 1936: Sixteen Days in August, by Oliver Hilmes

From an award-winning historian and biographer, the 1936 Olympics told in the present tense, through the voices and stories of those who witnessed it. Berlin 1936 takes the reader through the XI Olympiad in 16 chapters, each opening with the day’s weather and, with the help of translator Jefferson Chase, describing the events in the German capital through the eyes of a select cast of characters — Nazi leaders, foreign diplomats, sportsmen, journalists, writers, socialites, nightclub owners and jazz musicians.

A Dangerous Woman: American Beauty, Noted Philanthropist, Nazi Collaborator — The Life of Florence Gould, by Susan Ronald

From the author of Hitler’s Art Thief comes a revealing biography about a fabulously wealthy socialite and patron of the arts. In Paris, Gould entertained the Fitzgeralds, Hemingway, Picasso, Joseph Kennedy and Charlie Chaplin, with whom she had an affair. During the Nazi occupation she had affairs with Germans and became enmeshed in a money-laundering scheme for fleeing high-ranking officers. In New York after the war, her money bought her respectability as an important contributor to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wallis in Love: The Untold Life of the Duchess of Windsor, the Woman Who Changed the Monarchy, by Andrew Morton

Using never before seen records along with letters and diary entries, Morton’s biographical portrait of Wallis takes us through the cacophonous Jazz Age; her romantic adventures in Washington and friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt; her exploits in China and beyond; and her entrance into the strange wonderland of London society. During her journey, we meet an extraordinary array of characters, many who smoothed the way for Wallis’ dalliance with the King of England, Edward VIII.

Renoir’s Dancer: The Secret Life of Suzanne Valadon, by Catherine Hewitt

Hewitt delivers a fantastic biography of the daughter of a provincial maid who found her way to Paris and became a part of the Impressionist art movement. Having affairs with many painters and a model for Renoir and others, Valadon was an ambitious, headstrong woman fighting to find a professional voice in a male dominated world.

The Seabird’s Cry: The Lives and Loves of the Planet’s Great Ocean Voyagers, by Adam Nicolson

Seabirds have always entranced the human imagination and New York Times best-selling author Adam Nicolson has been in love with them all his life: for their mastery of wind and ocean, their aerial beauty and the unmatched wildness of the coasts and islands where every summer they return to breed. Over the last couple of decades, modern science has begun to understand their epic voyages, their astonishing abilities to navigate for tens of thousands of miles on featureless seas, their ability to smell their way toward fish and home. The Seabird’s Cry examines the science and the stories of seabirds and the current crisis of seabird decline.

Full Battle Rattle: My Story as the Longest-Serving Special Forces A-Team Soldier in American History, by Changiz Lahidji and Ralph Pezzullo

Recognized as one of the finest noncommissioned officers to ever serve in Special Forces, Changiz’s story after more than 100 combat missions in Afghanistan and 24 years as a Green Beret is an amazing tale of perseverance and courage, combat and a man’s love for America. The memoir is a first by a Muslim member of Special Forces.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

The Word Collector, by Peter H. Reynolds

Vociferous, effervescent, torrential, guacamole, dream. Jerome collected words. Short and sweet words, two syllable treats and multi-syllable words that sound like little songs. The more words he knew, the more clearly he could share with the world what he was thinking, feeling and dreaming. What happens when Jerome decides to share his collection changes not only him, but everyone around him. (Ages 4-8)

If I Had a Horse, by Gianna Marino

Horses are the world’s best teachers as seen in this stunning, simple yet profound little book. They teach patience, gentleness, bravery, kindness, friendship, persistence, tolerance and cooperation. Perfect for horse fans, art lovers and anyone in need of a little encouragement. (Ages 4-8)

Tiny and the Big Dig, by Sherri Duskey Rinker

From the author of the beloved Goodnight, Goodnight, Construction Site comes this plucky little picture book that proves even little folks can do great things when they just dig in and stick to it. Tiny the pup proves his determination to everyone in this cute story in the vein of The Little Engine That Could. (Ages 3-6) PS

Compiled by Kimberly Daniels Taws and Angie Tally.

In The Spirit

The Face of Alley Twenty Six

Rob Mariani makes an impression with his delicious tonic made from scratch

By Tony Cross

If you’ve kept up with some of my columns, you’re starting to see that in the world of spirits and cocktails, quality ingredients make for a better drink, from having a quality spirit (remember, quality doesn’t always mean pricier), all the way down to making a simple syrup from scratch. The market for small-batch ingredients is huge right now. I jumped on the train when I started bottling my own tonic syrup. Although I have one of the few local tonics on the market, there is a nearby company that started retailing their tonic syrup before me. I’m talking about Alley Twenty Six Tonic, created and packaged by the boys over at their bar in Durham.

The first time I tried Alley Twenty Six Tonic, I was at a meeting with the distribution company that carries my tonic syrup. One of their concerns was having similar syrups with the tonic from Durham. Luckily for me, our syrups are as delicious as they are contrasting. While my syrup has a more pronounced bitterness with baking spices, Alley Twenty Six Tonic has more of a sweet cola flavor with a touch of bitterness. The other major difference between the tonics is the fact that Rob Mariani, one half of Behind the Stick Provisions, has his syrup in way more places than I do. That’s an understatement.

Rob is the kind of person who makes a big first impression. Tall and lanky, with an imperial, handlebar-style mustache and his signature flat/newsboy cap, he always has a smile on his face. I first met him a year and a half ago at a local distillery party, and most recently sat down with him in Durham over a few of his tonic drinks.

Originally from Estonia, and raised in New York City, Rob didn’t find his passion for bartending until after moving to New Zealand in the beginning of the millennium. “I landed in Wellington and stayed there for a year. A friend hooked me up with some guys building a nightclub. I was doing construction, and at the end of the build decided that I wanted to learn to bartend there. My shift was from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. It was a blast. I was hooked.”

Rob left New Zealand and found himself bartending at high-end restaurants in Washington D.C., including Agraria (now called Farmers Fishers Bakers) with D.C. celebrity Derek Brown. Mariani relocated to Durham afterward and helped open Alley Twenty Six in the fall of 2012. Alley was launched by owner Shannon Healy, formerly of Crook’s Corner in Chapel Hill. Healy and Mariani started making their own mixers and syrups from scratch. Healy’s recipe for their tonic syrup was a hit; that’s when the light bulb went on. Healy and Mariani launched Behind the Stick Provisions and started bottling their tonic syrup for retail. “The market for cocktail syrups was growing, and we wanted in,” says Rob. “We decided to launch our retail brand with tonic syrup because there were only a few on the market, and frankly, we liked ours better.” Rob took the original recipe, and slightly tweaked it for larger scale production.

As tonic sales blossomed, Rob realized he would need to transition from behind the bar to Behind the Stick. “After 15 years of bartending, I saw this as a great opportunity to shift jobs in my industry career. I didn’t want to leave, I just didn’t want to work till 3 a.m. anymore,” he says. “This was the logical next step for me. Now I get to work with bartenders, distillers, home cocktail enthusiasts, and an amazing cross section of the industry.” And that he has. Just follow him on Instagram (behindthestickprovisions) and you’ll see the myriad places he pops up.

As we sat down to talk, Rob had one of the barmen make me a daiquiri with his tonic syrup in place of simple syrup. As I finished it in four sips (absolutely delicious), he explained that his tonic will soon be in Moore County, hopefully by the time this column hits the street. He said he usually likes to substitute his tonic syrup in place of a traditional sugar syrup to give certain classics a spin. He also explained why he loves using his tonic in rum (and his love for rum).

I found a new bestie. I’d lie if I said I didn’t sit there at least a little jealous while he told me of his adventures to Trinidad and Martinique to visit rum distilleries. He has an upcoming trip to Barbados in February, where he plans on learning more from different distilleries, such as Foursquare and Mount Gay. I know why rum is my favorite spirit, so I asked him why it’s his.

“Rum is a versatile and misunderstood spirit,” he says. “It can be made from various forms of sugar — molasses being the most common — but pressed sugar juice for rhum agricoles has amazing earthy, grassy and funky notes that really bring the term ‘terroir’ to rum.” His recent “rum adventures” include scouting trips for places to live in the distant future. I can’t wait to visit my new bestie wherever the island may be. PS

Tony Cross is a bartender who runs cocktail catering company Reverie Cocktails in Southern Pines.

southwords

Bill and Me

Just another day in February

By Jim Moriarty

The film Groundhog Day was selected for inclusion in the National Film Registry in 2006. Under the auspices of the Library of Congress, the Registry aims to ensure that America’s film heritage doesn’t disappear into the ether like so many of Hollywood’s earliest films did. Blazing Saddles, Fargo and Rocky were in the same graduating class.

Five years after his film was soaked in STP, or whatever it is they do to make sure it lasts longer than the pyramids, I ran into Bill Murray on the 18th green at Pebble Beach. It was just myself and about a hundred other people who surrounded him after he and some guy named D.A. Points won the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am, which also happens in February.

Murray had been the tournament’s big celebrity for decades, bigger even than one of Pebble’s owners, Clint Eastwood. His on-course antics were panned early on by the golf-is-a-religion crowd, but most people came to enjoy the show. Between shots Murray routinely scanned the gallery, looking for just the right person to become his foil, for good or ill. One year along Pebble’s fourth hole I watched him approach a mom and dad and their adorably dressed daughter, who was in the 4-year-old range. Ignoring the parents, he wagged his finger impishly at the little girl and said, “You look very put together today.” The smile on her face ran all the way from the tee to the green.

Like my own Groundhog Day, I’d been after him for a sit-down interview for years. Finally, one February, he looked at me, exhaled deeply, and said, “You know, interviews are, like, my least favorite thing to do in the whole world.” Murray doesn’t do a lot of things on his least favorite list — unless he has a new movie coming out and you’re The New Yorker — and I was clearly one of them. But now I had him cornered between the Lodge and the Pacific Ocean. Just making the cut in Pebble’s pro-am is, as the current resident of the White House would say, YUGE. But winning it? That’s priceless. Hey, you get your name on a rock by the first tee.

So, there I was. Just Bill and me. And suddenly I realized, I had to think of something to ask him. So, I went deep. “What did you get a bigger kick out of,” says I, “having a film in the National Registry or winning this?”

He stopped for a moment, then looked at me kinda the way he looked at that poor schmuck who was taking the mental telepathy tests next to the pretty blonde coed at the beginning of Ghostbusters. “The National Registry is pretty cool. That’s going to last a long, long time. But,” and he paused to put his hand on the electric shock button, “I wanted this. And I don’t want very much.”

Because there’s a website for everything, there’s one dedicated to listing most of the things February’s days commemorate, including Groundhog Day. For a month with so few days, little February seems to pack a lot of distinction into them, some more serious than others. A couple of pretty good presidents have birthdays in February. And, of course, there’s Valentine’s Day which, appropriately, is also National Organ Donor Day. National Freedom Day is the 15th. That celebrates Lincoln’s signing of the joint resolution that would become the 13th Amendment, abolishing slavery. And Feb. 3 is The Day the Music Died Day, remembering the plane crash that claimed the lives of Buddy Holly, Richie Valens and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson.

Other days are slightly less poignant. There’s Don’t Cry Over Spilt Milk Day on the 11th and National Drink Wine Day on the 18th, which is followed, I presume not coincidentally, by National Handcuffs Day on the 20th. Animals, both domestic and wild, are not forgotten. International Dog Biscuit Appreciation Day is the 23rd, and International Polar Bear Day is the 27th. The month ends with one of my personal favorites, Public Sleeping Day. In leap years it must surely be followed by Little Bit of Drool at the Corner of Your Mouth Day.

But, whatever day it is, in February my mind inevitably returns to Murray. As Phil Connors says, “It’s the same things your whole life: ‘Clean up your room. Stand up straight. Pick up your feet. Take it like a man. Be nice to your sister. Don’t mix beer and wine, ever.’ Oh, yeah. ‘Don’t drive on the railroad track.’” PS

Jim Moriarty is senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.