Fiction by John Bingham

Illustration by Mariano Santillan

The mystery story that follows was written by John Michael Ward Bingham, the seventh Baron Clanmorris, appearing first in The Illustrated London News around Christmas 1954. Bingham was the author of 17 thrillers, both detective and spy novels. During World War II, and for roughly two decades after, Bingham worked for MI5, the British secret service. He was the inspiration for the master spy George Smiley in John le Carré’s fiction. “He had been one of two men who had gone into the making of George Smiley,” wrote le Carré. “Nobody who knew John and the work he was doing could have missed the description of Smiley in my first novel.”

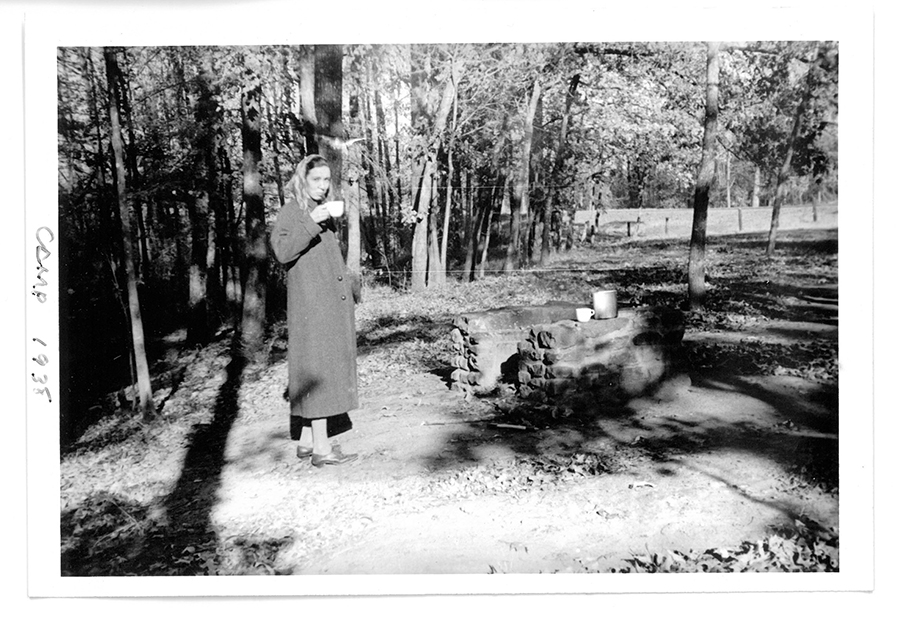

The weather was foul. It had been snowing, off and on, for some days, but during the last few hours the temperature had suddenly risen, and with the departure of the cold had come the rain, pitting the smooth snow, causing it to fall with soft rustles and sighs from the branches in the coppice which surrounded the cottage on three sides.

Bradley switched off his engine in the black-velvet shadows of the trees opposite the little gate; and went up to the gate, and saw that it bore the name “Lark Cottage,” saw, too, the soft lamplight gleaming through the chinks in the curtains of the front room.

It had been dark for two hours now. A blustery little wind had arisen, sweeping in chilly rushes across the moors, driving the rain before it, and plunging into the little hollow in which the cottage lay.

There was no other habitation in sight.

Bradley unlatched the gate and walked up a narrow path and knocked on the door. For a few seconds he heard nothing. Then came the sound of footsteps, but they did not come to the door. He heard them pass in front of the door, then begin to ascend uncarpeted stairs.

For a few seconds he stood listening, hearing the water drip from the eaves. A sudden gust of wind and rain, stronger than usual, caused him to turn up the collar of his raincoat.

Suddenly, somewhere above him, a window was opened, and the gust of wind died away, and in the silence that followed a woman’s voice said:

“Who is there? What do you want?”

“You don’t know me,” he replied. “I am sorry to trouble you.”

“Who are you?”

“You don’t know me,” he repeated. “My name is John Bradley. It will mean nothing to you, I’m afraid. I got lost, and now I’ve developed car trouble. The clutch is slipping badly. I see there is a telephone line to your cottage. I would be most grateful if I could use it. I’ll naturally pay you for the call.”

He looked up as he spoke. He could see the pale blob of her face in the darkness, peering down at him through the half-opened lattice window. For a second or two she said nothing. Then she said:

“Wait a minute. I’ll come down.”

He heard her close the window, and the sound of her footsteps on the stairs again, and the noise of the door being unbolted.

He followed her into the little hall, and then into the living room. The room was a curious mixture of dark oak furniture, solid and enduring, and cheap modern bric-à-brac.

In a far corner a small Christmas tree, obviously dug from the garden, stood in a red pot. A little girl, aged about 10, was decorating it with bits of silver tinsel. As he came in she held in her hand a small Fairy Queen, made of cardboard, and painted with some silvery, glittering substance.

She was fair-haired and pale, and looked at him gravely, uncertainly; poised, as though prepared to drop everything and run at the first harsh word.

Unhappy, thought Bradley; thin and unhappy, and none too fit. Aloud he said: “That’s a pretty tree you have.”

For a second, warmth crept into the child’s face and lit up the grey eyes, and she seemed about to speak. Then, as the woman spoke, the child thought better of it, and the face assumed again its former cautious expression.

“The phone’s on the windowsill.”

Bradley swung around and looked at the woman. She was about 35, tall and sallow, with dark hair and eyes, the hair brushed back severely from the forehead. Her features were regular and, but for the fact that she was thin, and that her face wore a harsh, embittered expression, he would have considered her handsome for her age.

Bradley said: “I suppose Skandale is the nearest town? Can you recommend a garage there?”

She shook her head. “You won’t get a garage to come out at this time of night.” She paused and added: “I doubt if there’s even a garage open, now, in that dump.”

“You are not from these parts?”

She shook her head again and said: “I come from Brighton.”

Bradley said: “You must find it a bit different up here.” But she was not listening to him. She was standing rigid, her head slightly on one side, as though she were listening. Her neck, her arms, her legs, her whole body was stiff. Bradley, glancing at her hands, saw that they were clenched and pressed to her sides.

But the child was different.

The child’s face was suddenly flushed and eager. She had stopped trying to fix the Fairy Queen to the top of the Christmas tree, and had turned her head towards the window, towards the front of the house and the garden path, and the gate through which a man would normally approach the cottage. She said:

“Did you hear anything, Mummy?”

The question seemed to break the tension. The woman said sharply:

“Julia! Either get on with your tree or go to bed — one or the other.”

The child turned back to her tree, but almost at once turned her head quickly to the window.

Bradley heard the click of the gate, too. So did the woman. The noise came during a momentary lull in the wind, so when the woman said it was the storm blowing the gate nobody believed her, and the child ran to the window and looked out, thrusting the curtains aside, and peering into the night, kneeling on the window seat, nose pressed against the pane. Bradley said:

“You are expecting somebody, perhaps? Well, I won’t bother you any longer. I’ll be on my way. Maybe the clutch will last a mile or two, and I’ll do the last stretch on foot. I take it this road leads to the main road to Skandale?”

The woman was staring towards the window, towards the child. Bradley thought: The child is eager, expectant, but the mother is afraid. At last she said: “It is at least 10 miles to Skandale. You would do better to stay here, Mr. Bradley, and catch the early-morning bus from the end of the lane. I can give you a bed.”

“But if you are expecting somebody — “

“Nobody is coming.”

There was a flurry of movement on the window seat, as the child Julia swung around and cried: “But, Mummy, it said on the wireless — “

“Julia! Come, it’s time for your bed.”

She went to the window and took the child by the hand and jerked her off the window seat and towards the door. At the door she paused a moment and said: “You are quite welcome to stay the night. Julia and I share the same room, and I will make up the bed in the small room for you.”

Bradley caught the strained, almost eager undertone in her voice, and knew that she wanted him to stay; knew that she was afraid and wished for his company in the house; afraid, even though as yet she had not said what she feared — or whom.

“Very well,” he said mildly. “I will gladly stay. It is very kind of you.”

He watched her lead the child out of the room, and heard them mount the stairs, and the sound of voices in an upper room, the woman’s sharp and scolding, the child’s plaintive. Then he went quickly to the window and looked out.

The light from the room was reflected by the snow, so that he could dimly see the garden and path and the gate. But there was no sign of anybody.

He had not expected to see anybody.

He lit a cigarette and wandered slowly round the room, glancing at the books in the bookshelf near the fireplace, at the cheap watercolors on the whitewashed walls.

On a table near the window stood a small silver tray. He picked it up and read the inscription in the middle, written in the impeccable copybook handwriting peculiar to such things:

to fred shaw on his marriage — from his pals at the mill

He replaced the tray and moved to the fireplace, noting the inexpensive china ornaments, the walnut-wood clock. In a light oak frame was a picture of a plump-faced man with fair, receding hair. In the bottom right-hand corner were the words: “To Lucy with love from Leslie.”

He wandered on, looking for something which he somehow knew he would not find; looking for the usual wedding picture, the wedding picture of Fred and Lucy Shaw.

He was not the least surprised not to find it; not in the least surprised to find no trace of Fred Shaw at all, except for the silver tray and that, after all, was worth money.

No trace, that is, until he came to the newspaper lying on the dark oak sideboard, and saw the double-column headlines, and read the text about Frederick Shaw, and how warders and police were scouring the countryside for him.

Frederick Shaw, aged 42. Escaped from Larnforth Prison.

Shaw, the murderer, reprieved because of what Home Secretaries call “just an element of doubt,” and serving a life sentence, with nine-tenths of it still to run.

Shaw, the former overseer, respected in all Skandale, who once or twice a year got a little befuddled with beer; who was known to be on bad terms with his uncle, the Skandale jeweler.

Good-natured old Fred Shaw, who never could explain how his cap and heavy blackthorn stick were found beside the battered body of the jeweler — or even what became of the money they alleged he had stolen.

Bradley put the paper down quickly when he heard the footsteps on the stairs. Too quickly. As he turned away, the big pages slipped over the side of the polished sideboard so that when Lucy Shaw came into the room she saw it lying on the floor and said: “So now you know, I suppose?”

“Yes,” said Bradley, “I know all right.”

Now that the need for acting was past, she stood in front of the fireplace, massaging one hand with the other, staring at him with frightened eyes. A tall, gaunt woman, with a wide, sensual mouth. The harsh expression had left her face. He saw her lips quiver.

“What are you scared of, Mrs. Shaw?” asked Bradley.

“I’m not scared, I’m not at all scared. What should I be frightened of?”

“That’s what I was asking,” said Bradley. He moved to the door and said: “I’ll go and get my suitcase out of the car.”

He went into the hall and out of the front door and down the garden path to the car. She heard the sound of the car door being slammed. On the way back, he paused by the front door. Then he came into the hall and put down his suitcase.

When he came into the living room he said: “Come outside a minute, will you?”

She swung round and stared at him.

“Why?”

“Did your husband — did Mr. Shaw use a walking stick much?”

“He always used one — almost always. He was a bit lame from a mill accident. Why?” And when he did not answer, when he only looked at her without saying anything, she repeated loudly, almost shrilly: “Why?”

“Well, come outside a minute,” repeated Bradley, and groped in his trench coat pocket for his torch. She walked into the hall, and when she hesitated by the front door he said: “Come on, it’s all right. I’m with you and I’m six foot tall and quite strong.”

The wind had dropped now, but the rain still fell; but softly, soundlessly, more in the nature of a moorland mist.

The snow was becoming soft on the surface but was still deep, so that the footprints round the house showed up very distinctly in the light of the torch; so did the small ferrule-holes in the snow on the left-hand side of the prints.

“I suppose he was left-handed,” said Bradley, more to himself than to Lucy Shaw, and saw her nod almost imperceptibly. He raised the torch beam a trifle and said: “See how he turned aside to look into the room? I suppose he saw me in there with you and Julia. I suppose he is waiting for me to go. Then he will come in and spend a few short hours with you, and perhaps take some clothes and money and go.”

He heard a movement by his side, and looked round, and found she had gone back into the house.

When he joined her in the living room she was sitting crouched in a chair by the fire. Her sallow face had turned white. She was trembling violently.

Bradley said: “I think I had better go, after all. I’m keeping him out in the night rain. It’s the police job to catch escaped convicts, not mine. I was a prisoner of war once. I’ve got a sneaking sympathy for them. Poor devil!” he added softly.

But she jumped to her feet, and clutched him by both arms, and said shrilly: “You mustn’t go! Please don’t go!” A thought struck her, and she added, almost in a whisper: “Before the gate clicked — you remember? — the child and I heard a sound. I think it was his hand, perhaps his fingernail on the windowpane, as he looked in through a chink in the curtains.”

Bradley said: “I’m going, unless you tell me why you are afraid.”

He pushed her from him, and she went and stood by the fireplace. After a while she said: “He thought I should have done more for him when he had his trial. He said he was with me at the time of the murder, and I should have said so too.

“But he wasn’t, so I couldn’t say it, could I? After all, you’re on oath, aren’t you, Mr. Bradley?”

“You’re on oath all right.”

“So I couldn’t go and perjure myself, could I? I mean, could I?”

“Men don’t kill women for not doing something, Mrs. Shaw.” He glanced at the gate. “The fire is dying, and there is no more wood. Where is it kept?”

She looked up at him fear in her eyes, and said:

“In the shed near the back door. I can’t go out there and fetch it. I’m not going out there alone.”

“I’ll fetch it. Just come with me and show me where it is. Just come to the kitchen door with me.”

He opened the kitchen door, and she stood with him, and pointed to the shed, a few yards away. The rain still fell, still soundlessly. Somewhere some water was running, gurgling down a drain. Otherwise there was no noise, either in the trees which pressed down upon the cottage or in the glistening bushes which edged their way to within a few feet of the back door.

He shone his torch, first on the shed then on the bushes, and took a step forward, and suddenly stopped as the bushes shook violently and snow cascaded from them.

Behind him he heard Lucy Shaw gasp and sob twice.

“It’s probably only a rabbit,” said Bradley, and walked towards the bushes. For a second he shown his torch at them, then made his way to the shed and gathered a trugful of sawn logs and came back towards the kitchen.

Lucy Shaw stood watching him, afraid to go back into the house alone, afraid to go out into the night with him. She kept passing her hand over her smooth hair, nervously, restlessly, staring out into the night at him with her black, dilated eyes.

The crash of the broken window, the broken living-room window, made her turn and scream; caused Bradley to break into a run; and woke up the child. Bradley heard her calling: “Mummy! Mummy! What’s that?”

Bradley carried the trug with one hand and with the other pushed Lucy Shaw into the house and whispered fiercely:

“Tell her I dropped a vase! Go on, tell her that!”

When the woman had done so, they went into the living-room and saw the stone with the piece of paper wrapped around it lying among the shattered fragments of windowpane. Bradley picked it up and smoothed out the paper, and saw, in capital letters, the word, ADULTRESS. He handed it to Lucy Shaw and said: “He doesn’t seem to think an awful lot of you, does he?”

The curtains were stirring in front of the jagged hole in the window. Bradley flung the logs down by the side of the fire and said abruptly: “I’ve had enough of this! I’m going. You can sort it out yourself with your husband. It’s no affair of mine.”

She flung herself at the door, ashen-faced, and stood in front of it, barring his way. “You can’t leave me here — alone!”

“Who can’t?” asked Bradley tonelessly and watched the curtains billowing into the room as a sudden gust of wind struck them.

“Where are the police?” gasped Lucy Shaw. “Surely the first thing they do is to send men to watch an escaped convict’s home?”

Bradley point to the telephone. “Ring ’em up and tell ’em so. Ask them where they are,” he said. “Go on — ring them up.”

She ran to the telephone and lifted the receiver and listened. When a few seconds had gone by, Bradley said:

“Perhaps the wire is down with the snow. Perhaps he’s cut it — you never know. They do it in books.”

After a minute, the operator answered. Lucy Shaw held her breath for a few seconds to control her voice, to try to restrain the tremor. Then she said: “I want the police! Tell the police to come! This is Mrs. Shaw, Lark Cottage, Oak Lane, off the Skandale-Tollbrook road. Tell them it’s — it’s very urgent! My life is in danger! My — there’s an escaped convict — a murderer — trying to get in!”

She replaced the receiver and stared at Bradley. He glanced at his watch and said:

“They’ll probably be here in half an hour. Three-quarters, at the most. You’ll be all right till then, I expect.”

He moved towards the door.

She did not move, unable to believe that he was really going.

“It’s no business of mine,” he pointed out for the second time. And when she clung to him and began to whimper, he said: “Don’t be daft. He won’t kill you for not perjuring yourself at his trial. He won’t even kill you for carrying on with this podgy-faced blonde brute.” He waved towards the picture on the chimney piece. “Once he’s in the house, you can appeal to him.”

But she clung to the doorhandle, gaunt and unlovely, her black hair now in disarray, and when he tried to move her hands she suddenly flung herself against him, temporarily forcing him away from the door, and said:

“It’s worse than that. He knew Leslie and I were in love, long before his uncle was killed.”

“So what?” said Bradley and moved again towards the door.

“You fool!” gasped Lucy Shaw. “Don’t you understand what I’m trying to tell you? Leslie — Leslie Bond — traveler for Fred’s firm, killed the old man, and stole the money, and planted the evidence against my husband, Fred Shaw — and I knew he had done it!”

“Did you now?” said Bradley mildly. “What’s that to me?”

“And I let Fred go on trial for it, and I’d have let him die for it, too — and he knows it, and that’s why he’ll kill me if you go before the police arrive!”

“Fancy!” said Bradley staring at her. “And your friend, where is he?”

“He left the country, saying he would come back when the case had blown over.”

“And will he?”

“No!” said Lucy Shaw bitterly.

“Not voluntarily!”

As she spoke, her voice rose almost to a scream, and Bradley, watching the hatred flush her sallow face and stretch her mouth into a thin, straight line, knew that the end was at hand.

“Where is he?” he asked abruptly.

“In Melbourne, Australia, and I’ll damn well tell the police when they arrive!”

“You may be charged as an accomplice after the fact.”

“What the hell do I care!” shouted Lucy Shaw. “I’m not going to be done-in tonight, nor 20 years hence, to save Leslie Bond, and I don’t care who knows it!”

Bradley said, woodenly: “If that’s the way you feel, and since you wish to make a statement, I don’t mind telling you now that the police are here already.”

Lucy Shaw looked round. “Where?”

“Here,” said Bradley, and put his hand in his raincoat pocket and produced his warrant card. Almost automatically his voice reverted to a routine drone as he continued: “I am Superintendent Bradley, of Scotland Yard. Sergeant Wood, I believe, has been listening outside that broken window. If you wish to make a written statement, I have some foolscap sheets of paper and a pen.

“I must, however, warn you that you are not obliged to do so, and that anything you say, or any written statement you make from now onwards, may be used in evidence against you. I should perhaps add that your husband was recaptured some three hours ago within a few miles of the prison.”

“What with you skylarking around, trespassing, making footprints, and breaking windows,” said Superintendent Bradley later to Sergeant Wood, “and me extorting confessions through fear and subterfuge, there’s been enough crime committed at Lark Cottage tonight to fill a sheaf of charge sheets.

“Funny, how I always had an uneasy feeling about that case, even though I did collect the evidence which put Frederick Shaw in the dock. Lucky she didn’t attend the trial and know my face.”

He filled his pipe and added: “The kid’ll be glad to be back with her father for Christmas. I reckon she hated her mother. So did I, if it comes to that,” he said, striking a match.

“And so did I,” said Sergeant Wood. “I was frozen stiff.” PS

Crime at Lark Cottage by John Bingham reprinted by permission of Peters Fraser & Dunlop (www.petersfraserdunlop.com) on behalf of the Estate of John Bingham. Lightly edited for space and style.