Two Thousand Miles I Roam

Just to make this dock my home

By Bill Fields

I have a modest stash of record albums, LPs that spark memories of people, places and parties. The number of scratches pretty much tells where each ranked on my personal charts, but no visual cues are required to identify the vinyl that meant the most to me.

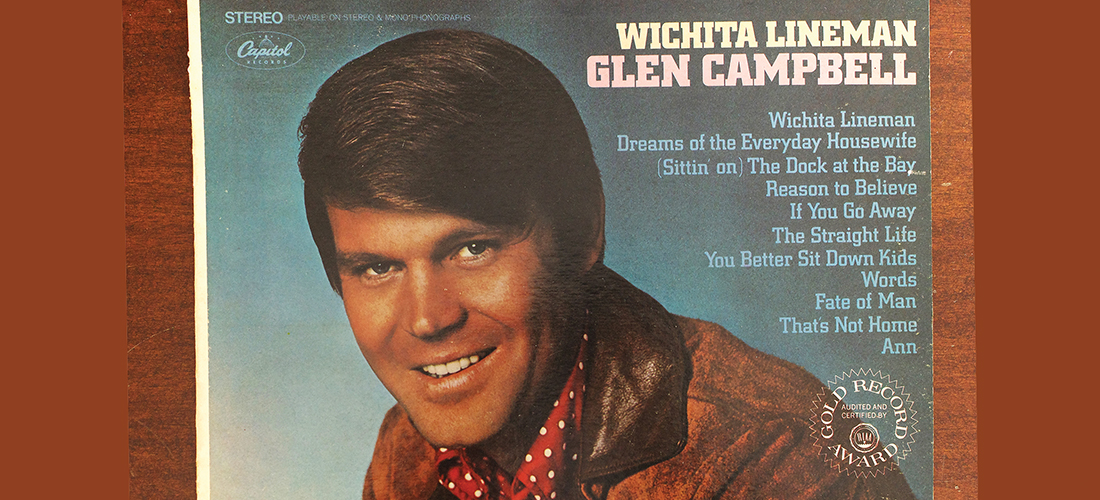

Glen Campbell’s Wichita Lineman was the first album I owned, and I thought it was 29 minutes of gold. It was released in November 1968, when I was 9 years old. Given that pop culture took the slow train to Southern Pines in those days, I obtained it a bit later.

The love of my first album coincided with my loathing of fourth-grade music and having to learn how to play the recorder. I didn’t like the teacher and couldn’t get the hang of the instrument. The combination caused me to loathe that class to a degree unmatched until calculus came along.

Amid the unpleasantness created by a one-dollar piece of plastic with holes in it, putting Wichita Lineman on the record player was bliss even though there was a lot of melancholy within the lyrics of those 11 songs. Campbell had a beautiful, pure voice and was, as I would learn, a world-class guitarist.

As I listened over and over to the album, Campbell became an obsession, my first outside of sports. If, in the summer of ’69, you’d told me I could meet either Brooks Robinson or Glen Campbell, I might well have chosen the famous Arkansan who didn’t play third base.

My mother and sisters could sing, and the Campbell record convinced me to see if I could, too, although there wasn’t a boys’ choir in America that would have signed me. I made up for the talent deficit with enthusiasm. Santa Claus brought me a TrueTone reel-to-reel tape recorder, affording me a make-believe opportunity to be a sports announcer or, after Campbell’s music became part of my life, recording artist.

I sang the title track plenty of times, but the second song on side one, “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay,” became my favorite. It was written by soul singer Otis Redding with Steve Cropper and recorded not long before Redding died in a plane crash in December 1967, when he was only 26 years old.

I must have heard Redding’s song played on the radio after it was released in early ’68, but Campbell’s cover was what I tried to mimic. I recorded it on the TrueTone and forced my parents to listen to me perform it live in the living room. I was far from being a lonely child, but Redding’s song of loneliness, sung by Campbell, fascinated me.

When Campbell came to town to play golf in the pro-am preceding the U.S. Professional Match Play Championship at the Country Club of North Carolina in 1971, he was the celebrity I was most eager to see, even though Mickey Mantle and astronaut Gene Cernan also were in the field. Campbell was dressed in yellow and offered a wide smile when I called out from behind a gallery rope before snapping a picture with my Instamatic camera. After the round, he signed my program. I collected many golfers’ autographs that day — Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Julius Boros and Ray Floyd among them — but at home that evening I lingered over the signature of the man whose music had meant so much.

About 20 years or so later, when karaoke had become a thing, I was in an airport hotel in Orlando, having arrived to photograph a story with well-known golf instructor David Leadbetter the next morning. I hadn’t sung outside the shower or alone in my car in years. But it was karaoke night at the Marriott, I knew no one in the crowded bar, and I wanted to sing. There was no doubt about the song.

I was waiting for my turn when I heard a familiar voice. It was my colleague John Huggan, a Scot with standards and opinions. Suddenly, I did know someone in the crowded bar. My plan for off-key anonymity was gone. Huggan and I chatted over a beer as a handful of karaoke performers grabbed the microphone. My name was called. The lyrics scrolled on a monitor but having sung “The Dock of the Bay” over and over as a kid, I could have done it without assistance.

I sang the song. A few people clapped. I warily returned to my barstool.

“You weren’t the worst,” Huggan said.

I considered it high praise PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.