Golftown Journal

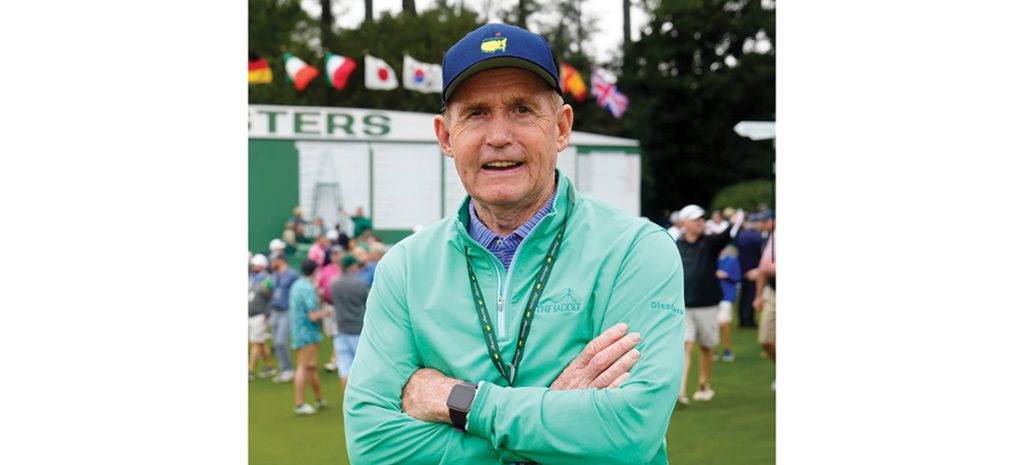

A Masterful Gift

The memories of Augusta in April

By Lee Pace

This month, for the 65th time, Lou Miller will enter the gates off Washington Road in Augusta, Georgia, buy a ham and cheese on rye sandwich for $3, and begin his annual treks up the hills and through the dogwoods of Augusta National Golf Club, sometimes clocking as many as 27,000 steps in a day. The grass will tweak his nostrils, the sun warm his face as he remembers jostling to watch Arnold Palmer back in the day, and seeing a limping Ben Hogan make birdie on his final hole in the 1967 Masters.

“There’s nothing like smelling Augusta National on Monday morning,” he says. “From there it’s a very special week. There’s nothing like it.”

The 79-year-old Miller attended his first Masters in 1958 at the age of 14 and has been to every one since (even wrangling access on the Saturday of the 2020 tournament held in November, when public attendance was suspended in wake of COVID-19). He grew up in Augusta, so to a golf-minded youngster the rite of spring known as the Masters was a big deal.

“I first played the golf course when I was still in high school,” Miller says. “The superintendent at Augusta National at the time was from our county, so he got us on. We played with no pins, but we still felt like we were playing in the Masters.”

What a first Masters experience that was, following a young Palmer around the course as he won the first of his four Masters, edging Doug Ford and Fred Hawkins by a shot.

“I like to say I was a ‘private’ in Arnie’s Army my first year,” Miller says. “By the time he won his second Masters in 1964, I was a ‘lieutenant colonel.’ I saw most every shot he hit those two weeks. Then you had Jack Nicklaus come along and challenge him. They fought it out for years, and Jack took the throne.”

Tickets weren’t difficult to come by in those days. He found various avenues into his early Masters and in 1965 started buying them himself — and he’s been on the list ever since.

“I had no money and couldn’t afford it, but I bought those Masters tickets anyway,” he says. “They were like $25 a ticket, and that was for the whole week. Shortly after, they announced they were oversubscribed and closed ticket sales. I was lucky.”

Miller in the early 1990s was moved by the awe and wonder on the faces of some guests he brought to their first Masters. He began a tradition of using his tickets on at least one tournament day to introduce first-timers to Augusta National. This month, he’ll escort two of his grandchildren onto the grounds. Over the years, he’s invited employees at clubs where he’s worked (today he’s president of Old Edwards Club in Cashiers, North Carolina), various friends and family members, and a few hard-luck stories of people whose lives would be brightened by a venture to the Masters.

“There’s nothing like taking somebody and seeing the awe and excitement and thrill of that person getting there the first time,” Miller says. “It’s seeing the excitement of the first thousand people on Monday morning. Every single time, it exceeds their expectations — whatever those were.

“I just love watching these first-timers smile. That thrill never grows old.”

By now some of you Pinehurst old-timers are going, “Lou Miller . . . where do I know that name?”

Miller was vice president and director of golf at Pinehurst from 1976-81. This was five years into the ill-fated Diamondhead era of Pinehurst’s history (the founding Tufts family sold the club and resort to Diamondhead on the last day of 1970), and one of Miller’s first jobs was figuring out why there were never enough tee times on Pinehurst No. 2 when the hotel was rarely at full capacity.

“The previous spring they were sending 150 people a day to other courses in the area,” Miller says. “The first people we fired were the starter on No. 2 and the guy working the starter tower over the clubhouse. We figured out they had direct phone lines and were selling tee times to golfers and pocketing the greens fees. We also had guests and members double-booking times. They would make one for first thing in the morning and another for later in the day. If they were too hung over, they’d show up for the second one.

“It was a mess.”

Miller was the first in an official capacity at Pinehurst to begin dreaming of a U.S. Open contested on No. 2 and actively courting USGA officials about the idea. He traveled to Baltusrol Golf Club for the 1980 U.S. Open to press flesh, and visited with USGA officers P.J. Boatwright and Frank Hannigan when the association conducted the World Amateur Team Championship on No. 2 and the U.S. Amateur at the Country Club of North Carolina later in the summer.

He even arranged a meal function with the USGA brass and Pinehurst’s new general manager.

“This guy was new to the job and said, ‘Oh, we don’t want outside events,’” Miller remembers. “‘We don’t need them.’ You talk about taking a nice warm shower and having cold water dumped on you. I wanted to throw him through the window.”

Miller left Pinehurst just as the banks were taking control of the distressed resort (later to be resurrected by the Dedman family and elevated gradually to its current status with three Opens already in the books, five more to come, and the USGA less than a year away from opening Golf House Pinehurst). Today he’s busy in Highlands overseeing a luxury inn and spa, a Tom Jackson-designed golf course, and a new 12-hole short course called The Saddle. He attended the Carolinas PGA annual meeting and trade show in Greensboro in February, then drove to Pinehurst the next day.

He played The Cradle short course, which was in part the impetus for building a similar venue at Old Edwards. “We wanted an amenity where three generations could play golf together, where you could be serious or play hit-and-giggle,” Miller says.

He sought out guys he’d hired nearly half a century ago, like Larry Goins at the resort clubhouse bag drop, and David Stancil downstairs working the carts and storage. He inspected the recently refurbished lobby and public area of the Carolina Hotel — quite the contrast from when Miller left in 1981 and the hotel was decorated with the greens and golds and shag carpet of the era.

“I love to hug the guys I know, smell the place, check everything out,” Miller says. “That hotel is gorgeous. They did an unbelievable job.”

Lou Miller’s a lucky man indeed. Seventy-nine and still going strong with memory banks full of Augusta and Pinehurst. PS

Lee Pace’s first book on the history of golf in the Sandhills, Pinehurst Stories, was published in 1991. Follow him @LeePaceTweet and write him at leepace7@gmail.com.