An encyclopedia of adventure

By Bill Fields

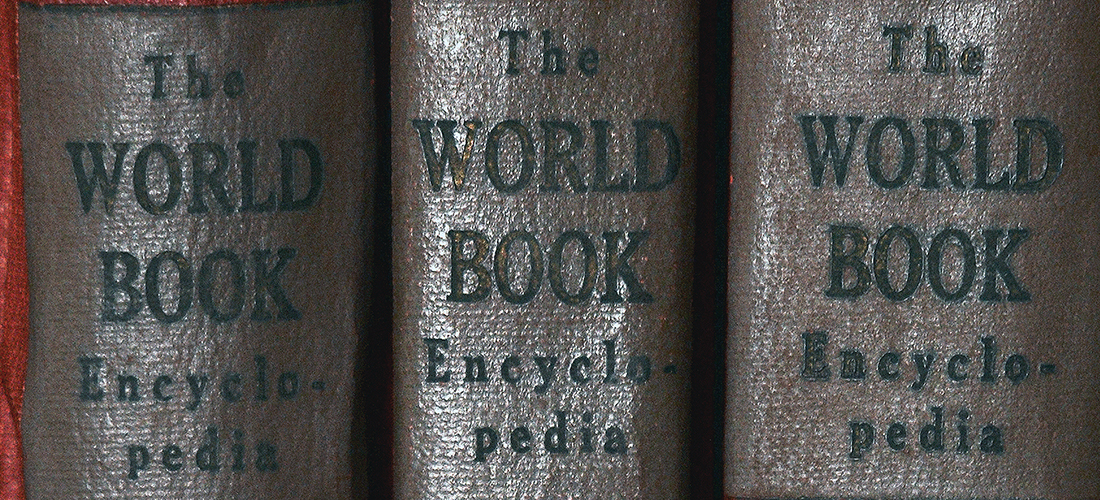

I pulled a volume off a shelf in a spare room and placed it on a table in front of my mother. Red with blue, gold and gray accents and fraying corners, it is seven years older than I am.

The World Book Encyclopedia, 1952 edition. I didn’t go to kindergarten, but I had our World Books, 18 volumes of information and entertainment, early childhood education without realizing it.

“They were a good investment,” said Mom, who couldn’t remember how much they cost on an installment plan those many years ago.

Whatever my parents paid for them, it was a fair price, and I think my mother has long forgiven me for the stray crayon marks and torn pages in the “Farm” and “Fire” entries.

For my older sisters and me, the World Books were a window to the world far beyond our neighborhood, our school, our community, our state — although once I could read and not just look at the pictures, I did get a charge out of the “North Carolina” entry and seeing Southern Pines, population 4,772, among the rundown of the Old North State’s cities and towns.

But the real joy was in discovering things I didn’t know — that would have been almost everything in elementary school and earlier — and there was something on nearly every page. Thanks to the World Books, a housefly wasn’t just a pest to swat but a creature whose body parts were diagrammed. “Thorax” remains one of my favorite words. Before I saw a live tadpole, I’d seen “Life Story Of The Frog” in the encyclopedia.

Much of the set was in black and white, which made the bright four-color maps of American states and foreign countries stand out and seem special. When I flew to Great Britain for the first time, in 1988, it was to a country I initially had seen in Volume 7 of our World Books, when the longest trip was in a car for a couple of hours to the beach. The encyclopedia’s maps triggered an early interest in geography. At filling stations in the days when they gave away highway maps, if one was on a shelf I could reach, I took it for my collection.

Some of the World Book maps look silly more than six decades later, freeze-dried coffee in a Keurig Cup era. There is no Soviet Union, and many countries in Africa have different names. To see the “French Indochina” entry that was published years before the Vietnam War is a jarring reminder of history.

Being fascinated by balls and games from the time I was a toddler, I pored over the sporting entries. The football helmets shown were leather and without facemasks in 1952, which had drastically changed by the early 1960s when I first started poking through the World Books. A football field, however, was 100 yards long then and now.

The same can’t be said for the “Golf” entry. The diagram showing “distances a very good player should get with various iron clubs” indicates a 5-iron going 150 yards, something that hasn’t been so for decades, thanks mostly to the construction of balls and clubs.

That golf chart was only one example of how the World Books presented information. A country would be superimposed on a map of the United States to show its relative size. A pie chart displayed the food elements in a grape. The leading tobacco states were denoted by illustrated rankings, North Carolina at the top of the heap! There was a two-page spread highlighting “French Literature” from the 1400s to the 1900s, something I bet my sisters looked at more than I did.

Along with school texts and library books, The Pilot and The Greensboro Daily News, the 1952 World Books were what I read until I was in the fourth grade and it was decided our encyclopedias needed to be updated. There was debate over whether we would stick with World Books or switch to Encyclopedia Britannica, sort of a Ford or Chevy thing.

I remember a saleslady coming to the house one night extolling the virtues of the 1968 World Books, handsomely covered in white and green. She was a good closer, and before long the original set had been retired. But never forgotten. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved North in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.