Roses are Red, Violets are Blue

Here’s a cheesy Valentine just for you

By Bill Fields

Best guess, they’re from third grade, half a century ago, when my loves were basketball, hamburgers and lightning bugs.

The envelope of Valentine’s cards wasn’t dated, but the greetings contain clues. Most telling is that a few of my classmates wrote their names or mine in cursive. It was a skill we were just learning. And you can sense the effort — intent look, pursed lips, tilted head at the kitchen table the night before — that went into every loop whether the writing was in pencil, pen or felt tip.

In some cases the penmanship, however labored, was better than the spelling. “To Bill Fills,” wrote one friend. Because I was someone who for the longest time thought people were saying “up and atom” when it was really “up and at ’em,” I should cast no stones. (But we were still ducking and covering, and there was an ominous bomb shelter sign at the cafeteria entrance.)

It was a very good time for puns, as indicated by my couple of dozen surviving cards, on which various creatures were utilized in the messaging.

“Valentine, you’re a Honey. Please BEE Mine.”

“I’d really Hoot and H’Owl if you’d be MY VALENTINE.”

“Ostrich your heart — to Include Me!”

“BeCows I Like You, Be Mine!”

Even if animals weren’t part of a pun they often were part of a card.

“You’re my Candidate for a perfect Valentine!” proclaimed a mouse.

“Wanted: Your Heart!” shouted a skunk.

“VALENTINE, I’m NUTS about you!” pledged a squirrel.

A number of the cards weren’t signed but others were. I received greetings from Becky, Bess, Billy, Bobby, Christine, Don, Eddie, Jeff, Jo, Katy, Lynn, Mark, Pat and Randy.

Some, I see on Facebook. Some, I know have passed away. Some, I have no idea.

Their names make me think of water fountains and blackboards, tetherball and teeter-totter, milk cartons and lunch boxes. I wonder if the unsigned cards were from other classmates or my leftovers.

We were very young, 9 years old or soon to be, on Valentine’s Day 1968, doing our best to absorb the lessons from our teacher, Peggy Blue, in reading, arithmetic, spelling and social studies.

For me, it’s possible it has been all downhill since the third grading period of third grade, when Miss Blue commented on my report card, “A fine student in all areas. Good thinker. Splendid manners.” Or, perhaps I merely threw no spitballs and banged the erasers against a pine tree at the end of the day when Miss Blue asked me. I will take credit for showing up regularly — only one day absent and no tardies.

Back then, there weren’t many burdens on a third-grader. Whatever happened in the classroom, there was ball to play after school and television to watch after homework: Family Affair, Bewitched, Lost in Space and Batman.

Not that Valentine’s Day wasn’t without pressure or consequences, because there were clearly choices to be made about the bag of cards each of us had bought at the dime store to distribute to our classmates.

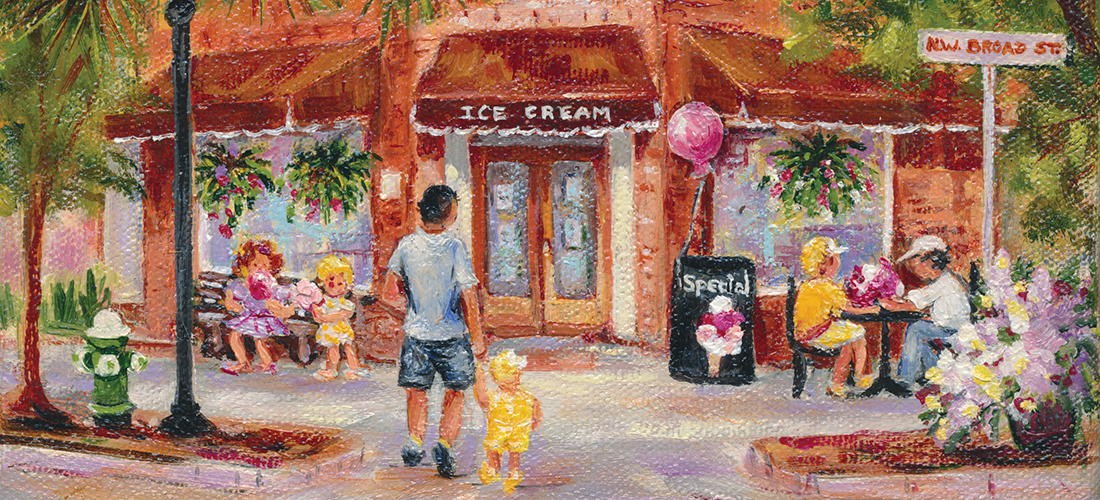

There simply was no way that a tiny cat-head card that said “You’re Nice!” ranked with a larger card of a scuba diver and two inscribed hearts, the top saying “Deep in My Heart I Want You,” the bottom reading “To Be My Valentine!” amid a backdrop of blue water and sea life — plus another tiny heart stuck by his air tank.

Likewise, receiving a 6-inch-tall, violin-playing clown saying “You Play on the Strings of my heart Valentine! Be Mine” pretty much meant that kid liked you. And can there be any doubt about the affection expressed in this card: a skydiver floating to Earth on a heart-shaped parachute asking, “May I Land on Your Heart?”

Jo won the day if not the boy. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.