The day chocolate rings hollow

By Bill Fields

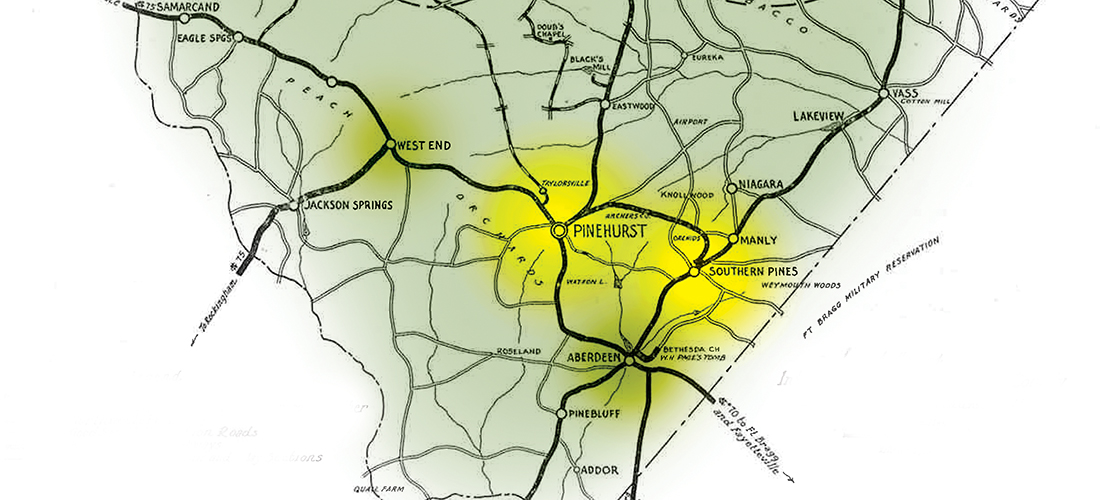

Growing up in North Carolina at a time when holidays weren’t hyped in stores nearly as much — certainly not as soon — as they are these days, there still were a few things to count on as Easter approached.

There would be a trip to the barber, even if a forensic expert might be required to discern the difference between a crew cut before and after. You were expected to look sharp.

And looking sharp didn’t mean just how you were groomed but how you would be dressed on this particular Sunday in spring. This could mean a shopping trip to Belk or Collins in Aberdeen or the Style-Mart on the corner of Broad and Pennsylvania.

It never ceased to amaze my mother how the same boy who would play for hours without a pause and be mad when it was supper time would complain about being tired, or having sore feet, within minutes of setting foot in a clothing store and before a single pair of pants, seersucker suit, clip-on bow tie or shoes other than sneakers had been considered for purchase. My unease on these excursions didn’t make logical sense, because they didn’t last too long. But all I knew was that I would rather be back at home doing something — anything, even listening to one of my older sisters’ Johnny Mathis 45s — than loitering in Boys’ Clothes.

The Saturday before Easter, there would be the hard-boiling and dyeing of the eggs. This ritual fascinated, in part because I’d seen the women in our house change the color of garments with Rit in a bathroom sink more than a few times. They were smart and didn’t let me assist with the sweaters because they were trying to get more use out of them, not have them come to an unfortunate end thanks to a careless child. I was happily encouraged to help out with the eggs, probably for two reasons: Seeing a chicken’s work go from white to a pastel shade wasn’t very exciting, and eggs were only about 60 cents a dozen.

On Easter, before church and a delicious lunch of baked ham with the appropriate side dishes — a meal whose predictable ingredients year after year made it that much better — the Easter bunny would make a delivery, the basket lined with fake grass a color green not found in nature. There would be jelly beans, of course, but the main event was a hollow milk chocolate rabbit enclosed in a box with clear plastic sides.

I loved chocolate, but it would have been a blessing for humanity if these candy mammals had come in a box that couldn’t be opened. There are only a couple of tastes from childhood that still make me frown. A stuffed pepper is one. As for those rabbits, their taste was like that of the material on which they sat — not of the natural world. They had a sickly, chemical-like flavor, making a Hershey bar seem like a treat for royalty. And once part of a chocolate rabbit had been consumed, what was left wouldn’t get any better. Unlike sweets that were good and within reach, the rabbit would linger until being thrown away only to reappear a year later. I always thought they would taste better next time, but they never did.

The Easter egg hunt, usually occurring after our big meal, was a distraction from rabbit redux. Since we hid real eggs, though, and not plastic ones filled with trinkets that have become so popular, this practice had its drawbacks too. If a couple of eggs were hidden too well, the smell would let you know a few days later.

There was a point where I got too old for a traditional Easter basket, but there was a transition period. I had taken up golf by then, and Mom gave me a sleeve of balls from the dime store. They had the compression of a marshmallow and would cut if you looked at them wrong, but that was just fine because they had replaced the hollow rabbits. If I had sampled them, they might have tasted better too. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.