A young man gone too soon

By Bill Fields

Even without the stories in the morning paper and the footage on the evening news, if you lived on the east side of town during the late 1960s, it wasn’t hard to figure out that America was at war.

Periodically our house rattled, and not from one of my father’s major league sneezes. It was artillery practice at nearby Fort Bragg, lots of it, particularly after a good rain. The shelling happened so often it almost ceased to startle, but the vibrations left cracked plaster on our ceilings and walls.

If only the real scars of the Vietnam War could be handled with a fresh coat of paint.

That point was driven home in September as I watched The Vietnam War, the 10-part documentary by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick on PBS. I was mad and sad well before the end of those powerful 18 hours of television. And I wished, more than anything, that Gary Nelson Frye could have watched too.

Born as World War II was ending, Frye also grew up in a house on the east side of town. He was a neighbor, a teenager when I was born. His mother, Mary O’Callaghan, was a family friend who for years sent me a birthday card and a couple of dollars. Gary went to East Southern Pines High School with my sisters. He was in the Class of 1964. For a time after graduating, he worked at the Proctor-Silex plant, where my father also had a job.

A little more than a year after he got his high school diploma, Frye enlisted in the Army on his 20th birthday. A year after that, as he turned 21 on August. 20, 1966, he was sent to Vietnam.

Frye hadn’t been there three months when he showed what kind of soldier — what kind of man — he was. On a search and destroy mission near Bong Son on Oct. 28, 1966, his unit was attacked. A radio-telephone operator with an artillery party, Frye called in accurate supressive fire.

According to his Silver Star citation, this is what happened next.

“… with complete disregard for his own safety, [Frye] raced forward under intense enemy fire to aid a wounded comrade. Finding the man mortally wounded, Private First Class Frye moved under fire to another casualty, carried the soldier to a covered position, then helped the company Aidman administer first aid …”

He earned another Silver Star for bravery, this time for running through enemy fire to direct supporting artillery and helping defend his platoon when it was trapped for nearly a full day.

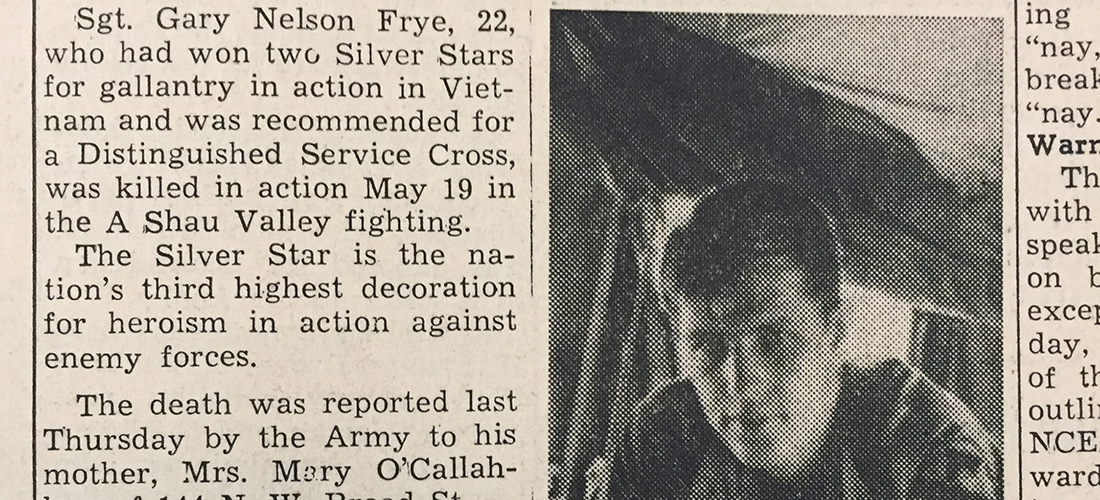

Frye volunteered to extend his time serving in Vietnam after a year. In May 1968, he had been in Southeast Asia 20 months and was due to come home to Southern Pines in a month. On May 19, in the A Shau Valley — scene of some of the worst fighting during the conflict and described in Part 6 of the Burns-Novick documentary — Frye was killed in action by an explosion.

Sgt. Frye was 22. I was a week from turning 9, and I went with Mom and Dad to see his mother after his death. She had moved out of the neighborhood and was living in an apartment downtown above Pope’s. It was a small place, full of folks paying their respects. Some of the male callers, like my dad, were veterans of a war that had a clearer purpose.

I wasn’t old enough to understand it all, but that space overflowed with grief exacerbated by the fact Gary was so close to returning to the U.S. when he was killed. I was old enough to understand some heroes don’t get the gift of years. Until my father became terminally ill a decade later, it was the most sobering event in my life.

As I grew up and began to read books on Vietnam — works by Graham Greene, Michael Herr, David Halberstam, Tim O’Brien, Neil Sheehan and others — Frye was in my mind, long after some of his fellow soldiers knocked on his mother’s door with the worst news, long after the rumblings of the war that claimed him stopped reverberating in the neighborhood.

Sgt. Gary Frye is buried in Mount Hope Cemetery, and his name is one of nearly 60,000 American names on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall. Thirty years ago or so on a visit to Washington, I located him on that wall. I stood there for a good long while, crying in the fresh air the way people were crying in that stuffy apartment two decades before, tears that did not come with answers. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.