Hometown

The Best Laid Plans

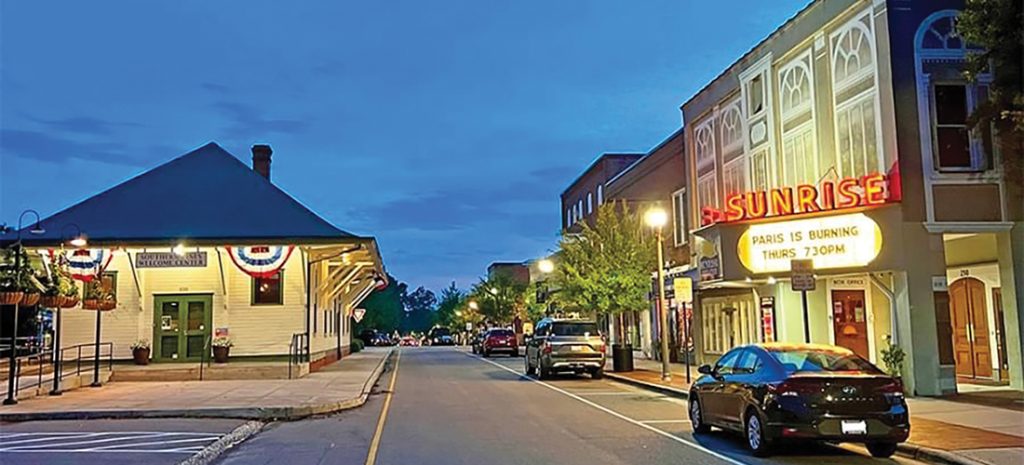

The resort that almost was

By Bill Fields

On childhood visits to sleepy Jackson Springs, where my parents grew up and my maternal grandmother still lived — across the street from the Presbyterian church — the stories told of the community’s bustling days were hard to believe.

As I tried to catch minnows in Jackson Creek or filled jars of mineral water from a spigot for Ma-Ma’s kitchen, few cars drove by on Highway 73. Inside the gas station once owned by my grandfather, B.L. Henderson, there was never a line to get to the penny candy or hoop cheese.

It was hard to imagine tourists in the 1890s and early 20th century having flocked to Jackson Springs, most traveling by train on the 4-mile spur line from West End, to take the water and take a load off, lodging at the 100-room hotel on a bluff above the springs. The guests went swimming and boating in a nearby lake. They played tennis, bowled and went quail hunting. Where I spent those solitary Sunday afternoons dangling a tiny hook baited with a morsel of bread, there had been a pavilion with music and dancing.

Why didn’t Jackson Springs endure as a resort, the way Pinehurst did?

There wasn’t any golf, for one thing, although in perhaps Jackson Springs’s most intriguing chapter, in the mid-1920s, there was talk of a course — designed by Donald Ross — among other big plans that never came to fruition.

News broke in 1925 that a “Northern syndicate” was purchasing the Jackson Springs Hotel from a local owner with intentions to invest $1 million in upgrades and expansion. The New Yorkers talked about building a new, larger hotel, converting the existing structure into a sanitarium and maternity hospital, and aggressively marketing the mineral water, lauded for its curative power.

The organization incorporated in early 1926. Its president was Dr. Joseph Darwin Nagel, a physician. Born in Hungary in 1867, Nagel immigrated to the United States in the 1880s and attended the Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. An author of medical textbooks, Nagel was affiliated with the Hotel Pennsylvania, then the world’s largest hotel, as medical director.

“A man of sterling worth and whose name carries confidence and assurance wherever it is known,” The Sandhill Citizen noted of Dr. Nagel.

The corporation’s general manager, Henry Stockbridge, told The Pilot in February 1926: “As soon as Donald Ross can get to it, we intend to have him establish an eighteen-hole golf course. We will enlarge the dam and raise the height of it to supply ample water power as well as to the advantages of the lake. We have other plans in view which will be unfolded when the time is ripe and which will make Jackson Springs a more prominent influence in Moore County than it is at present.”

Stockbridge’s boast turned out to be a fiction. In the late summer of 1928, Nagel wrote to Pinehurst owner Leonard Tufts, explaining that he hadn’t been able to devote the necessary time to make development in Jackson Springs a reality. “The thought occurred to me,” Nagel wrote, “that possibly you or some of your friends, might be interested in the property . . . ”

Richard Tufts, responding for his father, told Nagel that the family had operated the Jackson Springs Hotel “for several seasons” and knew full well what it would take “to put the place on a paying basis.”

The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 was a hammer to the Jackson Springs Hotel’s by-now tenuous existence. The resort chapter came to an end in April 1932, when a fire destroyed the hotel weeks before a new owner, Frank Welch of Southern Pines, planned to open it for the late spring and summer seasons. By the following summer, instead of tourists, Jackson Springs was filled with young men working at a Civilian Conservation Corps camp, one of dozens of CCC installations in North Carolina.

In 1961, by which time the heyday of my parents’ hometown was a distant memory, Dr. Nagel died at age 93 in Winter Haven, Florida, where he had long wintered and later retired. His brief and ultimately aborted involvement with Jackson Springs didn’t make his obituary. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.