GOLFTOWN JOURNAL

Talk the Talk

And put on the headphones

By Lee Pace

By April 2020, Matt Ginella had spent seven years on a dream assignment collecting and producing golf travel content for the Golf Channel. But that spring the world ground to a halt in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak. Ginella, for years a print journalist before moving to television, was at his heart a storyteller, and found himself with oodles of time and a vault of interesting tales gathered from pursuing the sport around the globe.

Prior to the pandemic, he’d been reluctant to jump on the podcast bandwagon. Here a podcast, there a podcast, everywhere a podcast — one of these newfangled instruments to deliver what was essentially a radio show. But a new venture he conceived with fellow journalist Alan Shipnuck called The Fire Pit Collective was the perfect venue for Ginella to begin generating hour-long conversations with the fascinating people he’d met in the game. The Fire Pit Podcast was born.

“One might say I had an epiphany,” Ginella says. “The world was grounded. We were quarantined. Yet people were still interested in a quality narrative. It was the perfect launchpad, an outlet for my passion for telling stories.

“Over the years, I’d had access to incredibly interesting and inspiring people. We always left some of the best stuff on the cutting room floor. We turned that upside down, put those out in podcast form. We are hyperfocused on the best story, the type of story told in a fire pit atmosphere after a full day of golf. Pour a drink and sit by the fire. We’re letting people stretch, letting them go and giving them time to tell their best stories.”

The result five years later is a library of nearly 200 podcasts encompassing personalities, travel, equipment, the greats of the game and major championships.

One of the most entertaining shows was a two-parter from August 2022, about the “Manning Brothers Buddies Trip,” when Eli, Peyton and Cooper Manning travel to Scotland with buddies like Eric Church, Jim Nantz and Taylor Zarzour, navigating — in intricate color and hilarious detail — the golf courses, bars and cemetery walls next to the Old Course. It took 14 interviews and eight hours of tape to get the story pat.

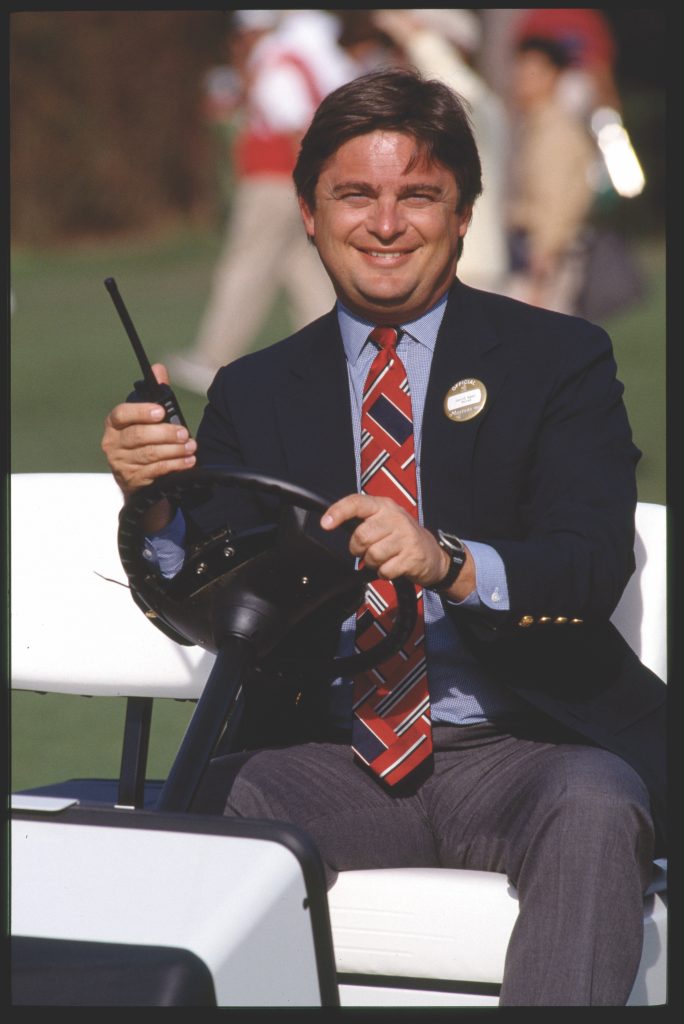

“For this old soul, to have buddies on the ultimate buddy trip allows you to experience it vicariously, by connecting me via Facetime worlds apart, to have me there live and in person, is a very nice gift,” Nantz says. “A gift of friendship. Golf does that to you.”

Indeed, it does. Golf has always been revered for its rich literary heritage, and now the spoken word through the podcast has a significant place at the table.

The podcast format has been around for about 20 years, the “pod” coming from the Apple iPod that was introduced in the early 2000s. Podcasts are best described as on-demand radio — audio content like you would find on the radio but available in episodes that listeners can stream from the internet anytime, anywhere, on venues like Apple Podcasts or Spotify. In time, video was introduced, and now podcasts are streamed on YouTube and other social media. There are some 600 golf podcasts on Spotify.

January marked the third year of the Pinehurst area Convention and Visitors Bureau “Paradise in the Pines” podcast. The podcasts are hosted by CEO Phil Werz, run about 30 minutes in length, and are posted (in general) every other Tuesday. The theme of the podcast is to share conversations with the people who make the Sandhills the “Home of American Golf,” with guests having a direct tie to the Sandhills whether it be for golf, business or other interests. Guests have included Mike Hicks, the caddie for the late Payne Stewart; Angela Moser, the lead designer on Tom Doak’s staff for Pinehurst No. 10; and Jamie Ledford, president of Pinehurst-based Golf Pride Grips.

“Social media content is one of the most important things we do as a destination marketing organization,” Werz says. “The podcast was simply another way to produce content via a popular mechanism.”

Chris Finn launched a golf fitness and rehabilitation practice named Par 4 Success in Durham in 2013, and the company has grown substantially over a dozen years into ever-bigger headquarters facilities in the Research Triangle Park. He launched a podcast in July 2023 called “The Golf Fitness Bomb Squad,” installed production capabilities in a new company headquarters, and now consistently produces an average of two podcasts a week. One of them features a guest — someone from the golf equipment, instruction, fitness or other disciplines — and the second is a shorter subject addressing topics like off-season conditioning, injury rehab or improving mobility.

“No one in the fitness or rehab space was doing anything research- and science-based,” Finn says. “We talk to top instructors, equipment guys, fitness experts and bring it back to golf fitness. We’ve had PGA Tour and LPGA pros, and long-drive champions. Fitness is the underlying thread. We take a casual approach to introducing people to the fitness world in an unintimidating way. We meet them where they’re at instead of talking over their heads.”

The “No Laying Up Podcast” will hit its 1,000th episode in 2025 in more than a decade of production. What started as a group text among college friends in 2014 has grown into one of the most popular podcasts in the game as it strives to provide fresh, funny and informative conversation on all things golf. In early February, the No Laying Up gang was at the AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am — won by Rory McIlroy — just weeks after doing a deep dive on “The Lost Decade of Rory in the Majors.” It generates significant content on the pro tours but also ventures into topics such as gaining clubhead speed with Dr. Sasho McKenzie, co-founder of The Stack System. And they have had good access to top-level guests like Tommy Fleetwood, Jim Furyk and Mike Whan.

In 2015 Andy Johnson, frustrated by traditional golf media, set out to generate his own newsletter. He found an audience, and in time it evolved into The Fried Egg website, which has a decided bent toward golf architecture. Often on “The Fried Egg Podcast,” he and co-host Garrett Morrison delve into intricate detail on the design, personality and playability of the world’s top courses. You’ll learn of courses you’ve never heard of but want to immediately put on a buddies trip list.

The Golfer’s Journal was launched in 2018 as a hefty print book being released quarterly. Its motto is “Golf in its purest form,” and the magazine and accompanying podcast are not interested in the newest driver or golf ball design or swing technique. They find the most interesting people, venues and stories to write and talk about. Author Tom Coyne hosts many of the podcasts along with editor Travis Hill. Wide-ranging subjects have included a multi-podcast history of the Masters and Augusta National; interviewing Bill Coore about his golf design travels and a personal trip to Antarctica; and how Padraig Harrington is one of the most interesting people in golf.

There are podcasts for all interests and tastes — humor, travel, the mental game, swing technique and history. Like courses in the Sandhills, there are plenty of options for golf junkies to get their fix.