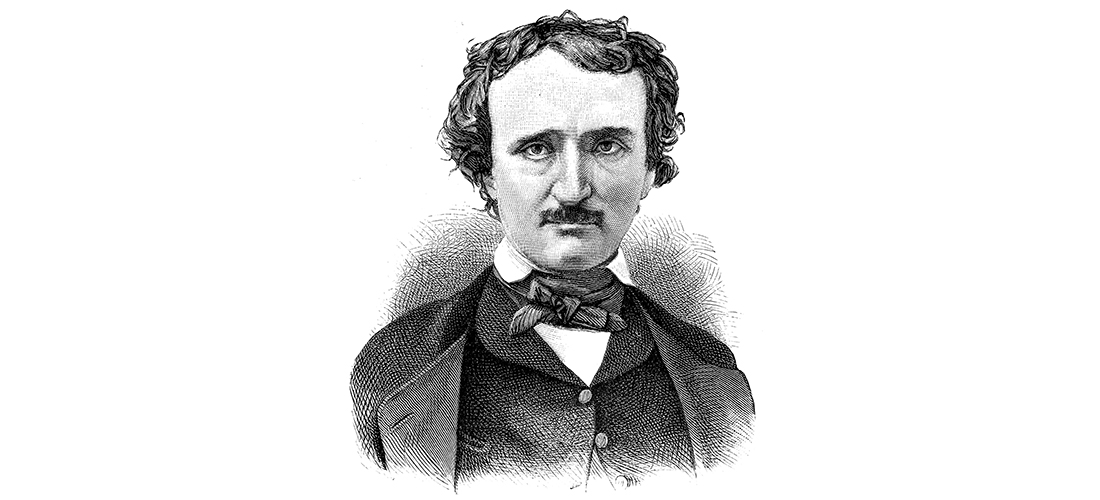

Edgar Allan Poe

Overcoming the misfortune of being born in Boston

By Nan Graham

One truth about the South can be found in Truman Capote’s famous quote: “All Southerners go home sooner or later . . . even if it’s in a box.” So too, I believe, it is true that once in the South, Northerners — or those from someplace else, as I call them (to avoid the Y word) — become “Accidental Southerners.” Even if here temporarily, they are profoundly and sometimes unconsciously affected by the haunting strangeness of our part of the world.

One such person is Edgar Allan Poe. Though born in Boston in 1809, Poe traveled the Southern theater circuit with his actress mother, Elizabeth, down the Eastern Seaboard from Norfolk to Charleston. She may have even played at Thalian Hall in Wilmington. I like to imagine toddler Edgar and his siblings in tow backstage. Later, the orphaned Edgar grew up in Richmond, Virginia, with foster parents, the Allans. Though New England born, Poe always considered himself a Southern gentleman.

A student in the first class at the newly opened University of Virginia under its founder and president, Thomas Jefferson, Poe was a good student but a wretched gambler. His foster father’s refusal to pay off his gentleman’s debt (a serious violation of a gentleman’s code of honor) resulted in the young Poe being ousted from the university. He eventually joined the Army, served in South Carolina as a private, then returned to college at West Point.

His career at West Point was as brief as that at UVA. First semester he received 44 offenses and 106 demerits. His second term shows a lack of improvement: In only a month he managed to accumulate 66 offenses. And the final straw? The story goes that Edgar Allan Poe showed up for “a dress parade wearing only his cartridge belt . . . and a smile.” The incident remains undocumented, but persists to this day, perhaps because it’s a great and hilarious anecdote.

Mr. Allan left the impoverished Edgar out of his will despite having left a sizeable inheritance to his illegitimate son . . . a son he never met.

Poe’s contribution to American literature cannot be discounted as a mere writer of horror stories. His impact on American letters is major. His is the first authentic American voice among the young country’s other writers whose works were, for the most part, pale imitations of Europe’s literature. He is the first original American author and the first widely famous Southern author.

Among his accomplishments, Poe wrote the first detective story (and detective, Inspector Dupin) in “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” inventing the genre we are addicted to even today. His ratiocination (what a word!), a method of solving a mystery by logical deduction and reason, cleared the path for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple.

Poe was the very first American literary critic. He was also an early developer of the short story form. “The Pit and the Pendulum” and “The Tell-Tale Heart” remain classics.

Why his claim (and mine) that he is a Southerner, despite his Boston birth? Mother Elizabeth had the good sense to die in Richmond and thus sealed Poe’s fate to be brought up a Southerner. Reared by his foster family in Richmond, he always considered himself a Virginian.

Women have been long idealized in the South, and few writers have been more obsessed with women than Poe. He lost his mother, wife and foster mother to tuberculosis. According to Poe, the death and loss of a beautiful woman was the most elevated of all subjects for poetry and literature. We see this theme repeatedly in his works: “Annabel Lee,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “Berenice” and “The Raven.” The writer’s focus on lyricism and language usage is also very Southern.

Much has been written on Poe’s sense of place, famous in Southern literature. His setting for “The Fall of the House of Usher,” in the phantasmagorical and swampy tarn, could be the low country South at its creepiest. Poe knew the Carolina low country. His short story “The Gold Bug” is set in Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, where he was stationed as a soldier — an island which today sports names like Raven Drive and Goldbug Avenue to honor the poet.

My last reason that Mr. Poe is really a Southerner? He married his first cousin when she was 14. I won’t even touch that one! PS

After 25 years of broadcasting commentaries for Wilmington’s PBS station, 40-plus years of teaching, and authoring two books, storytelling is still a passion for Nan Graham.