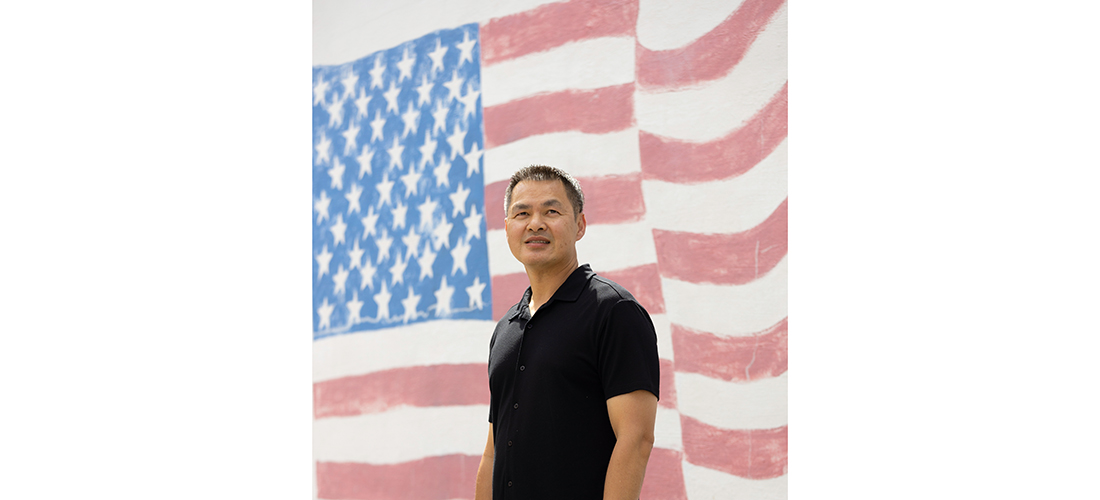

Vinh Luu and the American Dream

By Amberly Glitz Weber

Photograph by Tim Sayer

One early morning in 1979, Vinh Luu’s parents dressed him and his six siblings as if for school, before leading them cautiously out into the dark city streets of Saigon. Beneath those outfits, they wore as much clothing as they could put on, walking away from their family home with little more than the clothes on their backs. They were headed to an unnamed location to meet the smugglers they’d paid to arrange their escape. There they waited to be ferried in smaller, less conspicuous groups to board the rickety fishing boat they hoped would carry them to a new life.

The Luus had lived in Saigon since Vinh’s grandparents immigrated from China. His father worked as a dentist with the South Vietnamese Army, and his mother’s grocery business was the breadwinner for their large family. Vinh remembers her as a hard worker, and successful. Living in the capital city, the family did not see much bloodshed during the war years. “I remember after the fall of Saigon, you hear a lot of these celebrations by the Communists, shooting guns up in the air,” he says. “I remember seeing tanks tearing up the streets when they came in.”

After the fall of Saigon, the family stayed, hoping things would be better — they weren’t. In mid-1975 the Communist Army confiscated his mother’s grocery business, shutting down the entire supermarket with the promise that they would eventually return it to the local owners. His parents decided to flee soon after.

“You know, I think about it all the time,” Vinh says. “I can’t imagine bringing seven children, risking everyone’s lives for this trip. You take a chance at life; you have to make a decision. I can’t imagine just putting one life at risk, so for them to do that, it was desperate.” And not just their seven children — the Luus brought along extended family, loaning three uncles and numerous extended family the funds necessary for escape.

They paid extra — all in gold, as the currency was by then worthless — to ensure everyone was on the upper deck. Simple inland boats used mostly on the Saigon River, the holds were barely suitable for carrying any cargo, much less the human kind. During the escape, Vinh and his older sisters were separated from their parents and placed below deck. “This is a rickety old fishing boat,” Vinh remembers. “The smell of engine oil and saltwater down there — I passed out. When I woke up, I was completely naked. Literally, I was marinated in that engine oil, saltwater mixture.”

Eventually reunited with his parents on deck, his mother’s first concern was, “Where are your clothes?” Vinh’s infectious smile lights up his face as he gestures comically. “I’m like, ‘Mom, how am I!’ Come to find out later she had sewn gold necklaces and bracelets into our clothes to live off of at the refugee camp.”

Their ship floated in the South China Sea for nine terrifying days, struggling with broken engines, faulty navigation, seasickness, crowded conditions and little food. The passengers worked to stabilize the craft during storms, moving from port to starboard in an effort to avoid capsizing on the rough seas. Vinh remembers being so weak, he doubts he would have lived had they not made landfall when they did. One of his 2-year-old cousins died on the boat, as did his paternal grandfather. Their bodies were thrown overboard.

“After I reunited with my parents on the boat, I sat next to my dad. I don’t know when my grandfather died on the trip, but my dad, he was just bawling. I didn’t know why, and I cried with him. But now, looking back, I know why — either his father passed away, or he didn’t think that we were gonna make it.”

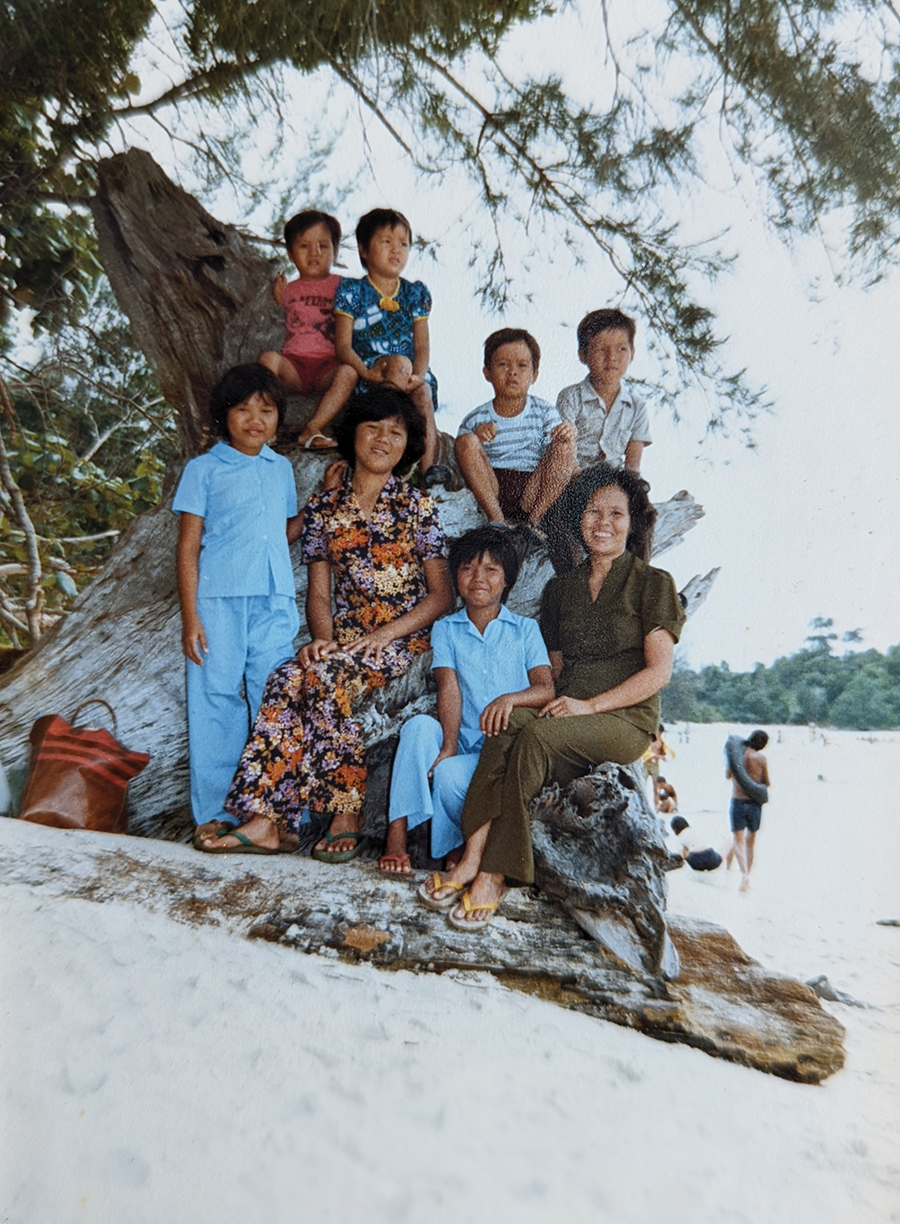

The boat landed on an isolated Indonesian island, where they remained for almost three months. Their boat disintegrated the day after landfall. Discovered by the island’s inhabitants, they were eventually moved to a more official camp.

“The first island we were on, it was like what you pay to go to now. It was like paradise. The men built huts out of coconut leaves,” Vinh says. They spent the next three months in the second, larger camp before being moved to Galang Refugee Camp, where they would be processed for relocation. The latter two camps were rife with disease. Vinh remembers being sick throughout, the family living in what amounted to a cardboard box.

He has a reminder of the camps preserved on one of the few family heirlooms to have survived the escape, a black leather tote bag. Marked on the bag and still visible is the family’s official refugee case number, which was used for everything in the camps, from housing to meals. It’s engraved in Vinh’s mind as well, a five-digit number he’ll never forget. He says it twice, first in Vietnamese and then in English — 62291.

Their stay in the camps was prolonged, since the Luus were determined to wait until space restrictions allowed for two conditions: that they go to America, and that they go together. Ultimately a church in Gastonia, North Carolina, sponsored the family. Vinh doesn’t remember much from his first sight of America, but he does remember his first days in Gastonia.

“We had a beautiful snowstorm. I ran outside barefoot — and came right back in,” he says and laughs at the thought of his cold-footed scamper.

That contagious grin is as etched on Vinh’s face as his family’s case number is on the leather bag. Starting school in Gastonia, he couldn’t speak the language. “I was pretty fortunate. We had a teacher’s assistant and she devoted a lot of time helping me. I was fortunate to have wonderful teachers growing up. They had an incredible, long-lasting impact on my life,” he says, his eyes beaming with gratitude.

Left: Vinh and his friends, Jason Jones and Dennis Muldowney.

Right: Vinh with his American mom and dad, Kathy and Jim Muldowney.

It didn’t hurt that he’s incredibly smart. It’s the first thing his close friend, Jason Jones, noticed about him. “The first time I heard his name was in algebra. Every time we had a test, our algebra teacher would announce who got a 100. She’d call out, ‘John Smith and Vinh Luu made a hundred.’ And then the next test, ‘Amy made a hundred and Vinh Luu made a hundred.’ And I was thinking, ‘Who is this Vinh Luu guy?’”

Despite having been in the country only a few years and still learning a new language, Vinh tried his hand at anything and everything. Jones produces their 1989 high school yearbook as proof. While keeping excellent grades and working as a grocery bagger at Food Lion, Vinh’s smiling face appears throughout the volume. Jones laughs and taps the Quiz Bowl Team image lightly. “Even though his English was bad, every week he would come and we would ask questions. And even though that was not his strength, he still wanted to learn; he still wanted to participate; he still wanted to just do it. That’s Vinh,” he says.

The two friends take trips together every few years. One took them to Las Vegas, where they elected to try something other than gambling on the strip. They rented bikes to ride the Red River Canyon, a challenging 30-mile trip. As the experienced cyclist, Jones could tell Vinh was struggling on the uphill, hot desert route. Every time he checked on him, Vinh’s reply was a quavering, “I’m O-O-O-K,” right up to the moment he dismounted and heaved his morning’s breakfast at the side of the road.

Jones wanted to call “a paddy wagon, or 911,” but Vinh wouldn’t hear of it. “And we finished that 30-mile ride. I couldn’t believe it — but that’s just the kind of guy Vinh is.”

Vinh’s older sister married and headed to San Francisco at the end of his junior year. His family decided to move with the newlyweds. Vinh went out that summer but found himself homesick for North Carolina. “There’s a big Asian community out there” he says, “and this is pretty funny, but I started school there, and I couldn’t find American kids. It was all Asian kids. And I was homesick. ‘Where are my American kids to hang out with?’” He laughs. His parents agreed to let him move home to Gastonia, where he stayed with his friend Dennis Muldowney’s family for senior year before enrolling at N.C. State.

His “American mom and dad,” Kathy and Jim Muldowney, say he’s been part of the family ever since. Jim gestures to a large photograph on the living room wall of their Raleigh home — a beautiful family portrait of children and grandchildren at the beach for a Thanksgiving reunion. Jim points to Vinh in the center of the frame. “That’s our family.”

“I joke he gets adopted by about 20 people a year,” Jones says of Vinh’s ability to make friends and create family. When an elderly neighbor mentions their worries about the long drive to a family wedding in Florida, Vinh volunteers to chauffeur them. A 90-year-old neighbor’s son visits regularly from out of state, and Vinh delivers him to and from the airport, refusing payment. A neighbor posts on the NextDoor app looking for assistance and Vinh answers the ad, generating another close bond.

Left: Vinh and his family.

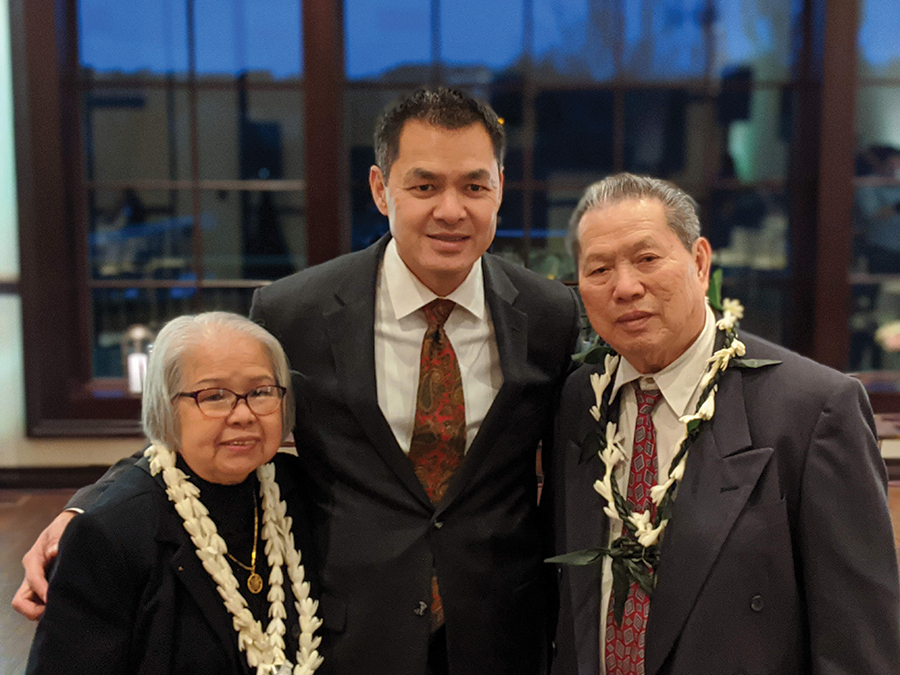

Right:Vinh and his parents.

As the oldest son, Vinh still maintains his family role as patriarch despite the nearly 3,000 miles separating him from his West Coast family. For him, there are no passing acquaintances — every relationship sparks a long and meaningful connection. Jones remarks fondly that although “Vinh’s never married, I don’t know anybody that has as big a family as he does.”

After graduating from N.C. State, Vinh began a long career at Ericsson Telecommunications, working in the Research Triangle. During the ’90s a new co-worker arrived from Iran, a political refugee who relied on Vinh for his advice and guidance. Years and a few out of state relocations later, the two stay in touch. Vinh’s a good mentor for anyone, but particularly for those seeking to build a new life.

“Assimilate,” he says, passing along his best advice. “Your roots and everything, it’s very important to carry on. But the faster you assimilate, the better off you are. And there’s nothing wrong with that, because this is your new life. And work hard. There are so many opportunities here, people don’t realize.”

While the family was blessed to find a welcoming community in Gastonia, they met with their share of challenges. Vinh still remembers the time a group threw rocks at their home, shattering windows before beating a hasty retreat. The experiences of his early years — a house fire in Vietnam that claimed the life of an older sister and his family’s terrifying escape from Saigon — could have been a struggle to overcome, the stuff of mental anguish.Vinh mentions that at one time he suffered from sleep paralysis, a sensation of being conscious but unable to move before waking, evoking terror and a sense of powerlessness. But Vinh has a superpower of his own, a buoyant nature and deep connection to others through simple, genuine kindness.

“It’s much different now than in the ’80s when we came here. People are more knowledgeable about things outside the U.S. and Americans are very — they care,” he says. “So, these refugees that end up here, I think they’re gonna be well taken care of. There’s hope.”

After Ericsson closed its R&D section in the Triangle, Vinh Luu’s expertise brought him to the Sandhills in 2016 to work as a contractor on mobile wireless technology for U.S. Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg. He feels as though he’s come full circle.

“You know, you have the Americans who went into Vietnam and fought for the South Vietnamese, us. And now, I’m doing work that protects the troops — keeps them safe, and America too, in that respect. It’s neat when I think about it. It’s more than a job, you’re actually protecting America.”

Service may be his profession, but his hobby is people. “I do a lot of stuff for some older folks that need help. I don’t have an exciting life,” he says with characteristic humor.

His friend Jason Jones goes to the heart of the matter. “Vinh is a good example of what America should be about — and has been about. This is why we are a country of immigrants, and this is why it is a dream.” The dream expressed by Martin Luther King Jr., “that every man is heir to a legacy of dignity and worth.”

It is an inheritance Vinh Luu earns every day. PS

Aberdeen resident Amberly Glitz Weber is an Army veteran and freelance writer. She’s proud to live in a country where there are Vinh Luus.