By Jim Dodson

After two years of being sidelined from a severe injury, I recently underwent knee surgery and began walking to work in the mornings again and with our dogs in the evenings.

Frankly I’d forgotten how good it feels — how walking through a busy world at a neighborly pace provides useful time to think and helps one notice important small things right in front of your nose.

“I tell people that I walk for sanity, not vanity,” says my friend Dennis Quaintance, the Greensboro hotelier who has been a dedicated daily walker in historic Green Hill Cemetery for years. “A walk helps me make sense of the world.”

The health benefits of a daily walk are also amply documented, and I’ve even managed to drop a dozen pounds since I resumed my regular walks three or four weeks ago. Soon I hope to be up to walking a complete golf course again, just in time for my wife and me to slip away to Scotland later this month.

In some ways my involuntary removal from golf prompted a true awakening. I probably took the ability to walk for granted and am both relieved and resolved to be back cruising the world on two feet.

Ditto my new friend and fellow golfer Kevin Reinert.

We met last Father’s Day at a family golf event I host annually for the Pinehurst Resort, a gathering of like-minded souls created around a surprise best-selling book of mine called Final Rounds, a story about taking my father back to England and Scotland, where he learned to play golf during the Second World War.

On the first night of the event I typically welcome 125 or so folks from around the country and give a little talk aimed at setting a lighthearted tone for golf and fellowship.

After this year’s opening dinner, a fit-looking fellow about my age came up to say hello with his wife, Jean.

“This is my first year here,” explained Reinert, offering me his hand. “I just want to say thank you for saving my life.”

I smiled, waiting for the punch line.

But there wasn’t one.

“No, seriously,” he said, “your book on Ben Hogan inspired me to get up and teach myself to walk again.”

And with that, he told me an absolutely extraordinary story of courage and one man’s resolve to put his shattered world — and legs — back together.

It was a beautiful evening a year ago this October when Kevin Reinert put his golf bag on a trolley at Greensboro’s Starmount Forest Country Club, hoping to get in a quick 18 before meeting Jean at a special fundraiser at the club. “It had been raining for days,” he remembers, “but the weather had suddenly cleared. It was a beautiful evening.”

Reinert, 62, is a retired Air Force colonel who spent almost 30 years working in recruiting and public affairs for the Air Force and Air Force Reserve. He was the administrator responsible for overseeing public affairs for 35 different Reserve units around the United States and the men who helped transform the Reserve’s recruiting profile.

Eleven years ago, Kevin and Jean, who met and married while both were captains on active duty in 1985, relocated from Georgia to Greensboro, where Kevin went to work for The Brooks Group, a leading sales management consulting firm. Before being deployed to Ramstein Air Base in Germany, Jean Reinert taught nursing at UNCG and returned from active duty to become nursing administrator for Cone Health.

“Greensboro was a place we fell for in an instant,” Reinert explained. “It has everything, great restaurants, theaters, wonderful people and a location that was perfect for us — the mountains in one direction, the coast in another. Our kids were grown and doing their thing, and North Carolina really felt like home.”

But all of that changed in an instant as Reinert pushed his golf trolley toward Starmount’s beautiful finishing tee.

“There was a group ahead of me, just out in the fairway, when my phone went off alerting me to incoming messages. I looked down, thinking it might be Jean, as I walked toward the tee. That’s when I heard this ferocious sound. I looked up but I didn’t quite register what I was seeing.”

What he saw was a Kia Rio with smashed side mirrors barreling directly toward him over the course’s cart path.

“I had just enough time to try and jump out of its way. So I jumped, hoping — I don’t know — that maybe I’d land on the hood and roll over the top like you see guys do in the movies. I didn’t get high enough,” he notes with a laugh.

The car struck him at the knees and knocked him over the hood and roof before barreling on. Reinert was tossed 30 feet from the site of impact, landing on the tee. The car was estimated to have been traveling anywhere from 35 to 45 mph, driven by a man who was on a violent robbery and mugging spree, trying to outrun the police. He managed to get one hole farther before the car went out of control and wound up in one of Starmount’s meandering creeks. The driver set off on foot, commandeered another car and was later apprehended.

“My first thought, as I lay there, was a kind of stunned disbelief. I saw that one leg was lying at a 90 degree angle from my body, and when I tried to lift myself up, my arm wouldn’t function.”

Workmen from a nearby residence hurried over, calling 911. The group ahead also rushed back. Reinert asked one of the golfers, a fellow member named Mike Corbett, to find his phone and call his wife. “Jean was over at UNCG and thought I said I’d been hit by a golf cart. She hurried over and actually got there before the ambulance did.”

Owing to heavy rains, the EMS unit couldn’t reach the spot on the course where Reinert lay, but head professional Bill Hall hurried out with a flatbed cart just as a fire unit arrived with a rescue board.

“They got me on the board and Bill drove me back to the parking lot, where the ambulance was waiting. It was a bumpy ride and he kept apologizing. I was probably close to being in shock but joked to him that he’d better not charge me for a cart because I’d walked the course. He thought that was funny. I also told him that if I’d parred the hole, I probably would have shot 87. He couldn’t believe I was conscious and making jokes. But I knew I was in pretty bad shape.”

Both Reinert’s knees were crushed. He’d suffered a shattered femur, a broken tibia, a broken right ankle and a fractured right humerus bone, the upper bone of the arm. “There was a deep cut on my face but, amazingly, no head injuries,” he said. “I was conscious the whole way, already wondering if I would be able to walk again.”

The next morning he underwent six hours of surgery. This was followed by four more surgeries over the ensuing weeks. “The doctors couldn’t give me a clear prognosis or even tell me if I would ever be able to walk or referee or even play golf again.” Besides golf, one of Kevin Reinert’s other pleasures was a budding avocation as a college-level lacrosse official.

After 18 days in the hospital, he was sent home.

He began therapy three days a week that continues to this day.

“The hardest part was just not knowing what was ahead. I sat and tried to watch TV, but the news was so discouraging I decided to turn it off and read books instead.”

An old pal from Long Island who taught him to play golf during their college years together at Adelphi University sent him a box of books, one of which was Ben Hogan: An American Life, my biography of professional golf’s most elusive superstar.

At the height of his success, while returning home from a golf tournament in Arizona, Hogan and his wife, Valerie, were struck head-on by a Greyhound bus that shattered Hogan’s legs and nearly killed the star golfer. His obituary, in fact, went out over the Associated Press wires before it was learned that he was actually hanging on in a rural Texas hospital. Doctors advised Hogan he would likely never walk again, much less play championship golf.

“Frankly I was really down before those books arrived, worried that I might not even be able to walk and play golf,” Reinert admits. “There were real similarities in our stories. I was so moved by his determination to somehow get back to the game — to simply walking — I vowed to myself that I would do the same.”

In 1950, at Merion Golf Club outside Philadelphia, Ben Hogan did indeed come back, capturing the U.S Open on a pair of legs that had little circulation — widely regarded as one of the most heroic comebacks in sports history.

Kevin Reinert made his own big comeback, too. One evening last May, family and 60 or so friends turned out to watch him finish playing Starmount’s 18th hole. “I was blown away so many folk came out to watch,” he said. “Everyone had been so encouraging. I’d made so many new good friends. The support I got from complete strangers was incredible. I simply wouldn’t have made it without them — especially my wife and children. My daughter LeeAnne, who is also a nurse, really pushed me at times.”

Son Phillip, an Air Force flight engineer working at the Boeing factory in Seattle, was also present to play that final hole with his father. He’d flown home the day after the accident on air miles donated by Mike Corbett.

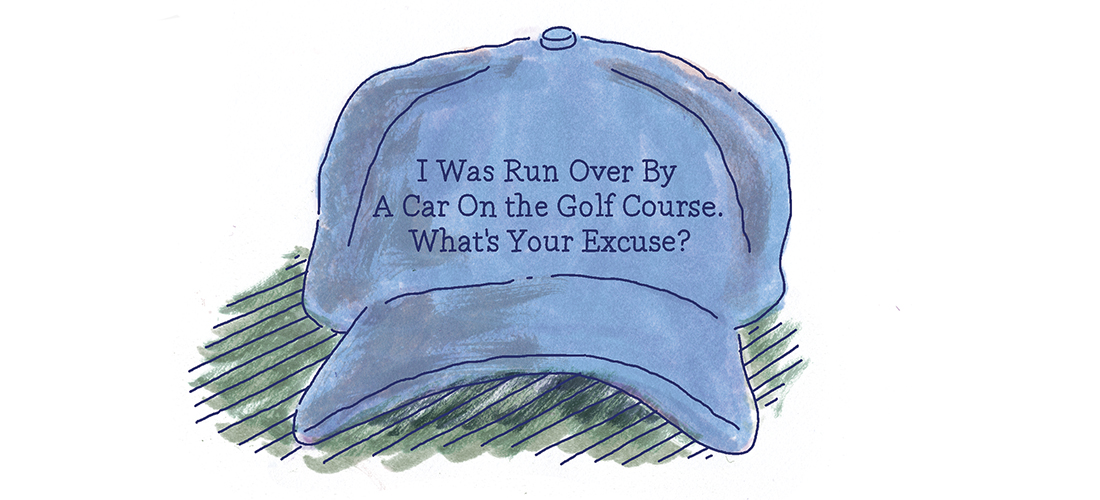

Reinert was wearing a cap given to him by a friend that cleverly read: I Was Run Over By A Car On The Golf Course. What’s Your Excuse?

Another gifted cap read Starmount 18: The Toughest Hole in Golf.

“It was very emotional for us all,” he says. “Made even more amazing by what happened before we teed off.”

On the facing hill, a Scottish bagpiper strolled out in full ceremonial regalia and began playing “Amazing Grace.” Another new friend offered to be Reinert’s caddie.

“Somehow I made bogey on the hole, which allowing for my handicap let me write a par on the card,” he explained to me as we played Pinehurst No. 4 on the first day of the Father’s Day golf fest.

It was his first full round of golf since the accident and he did very well indeed, shooting in the low 90s with both legs wrapped in athletic supports, just like Hogan.

The next day, he even walked mighty Pinehurst No. 2 with a caddie.

“This was one of the greatest weekends of my life,” he told me later. “It feels good to be back.” PS

Contact editor Jim Dodson at jim@thepilot.com.