Art of the State

Triumph in a Bridge

Matthew Steele celebrates the beauty of the manufactured world through sculpture

By Liza Roberts

Left: Gallery view of Mirrored Turbine, 2022, walnut, copper rod, 23-gauge nails, 84 x 84 x 4 inches. Commission through Hodges Taylor.

Right: Telophase no.1, 2022, oak and 23-gauge nails, 24 x 24 x 72 inches.

Infrastructure inspires Charlotte artist Matthew Steele. Bridges, highways, architecture and other physical manifestations of technology demonstrate to him the lengths human beings will go to “transcend the greatest obstacles we know.”

With honed precision, Steele’s work explores the elegance, complexity and rigor of such industrial and manmade structures, the labor that made them, and the life they each contain. The still rotors of a turbine become a thrumming work of abstract beauty when Steele makes them of wood and copper. He allows them to hang alone, the promise of movement in every blade. Steele’s scaffold-like towers of walnut merge to create a geometric, jagged skyline, but with an irregular, tendriled base: Are they putting down roots? Are these structures not built, but alive?

“There is desire in a highway,” Steele says. “There is triumph in a bridge.”

Steele moved to Charlotte in 2012 for a McColl Center residency and has made the city his home. “I’ve always been interested in the manufactured world,” he says. “I came from a super small town in Indiana. I knew the feeling I had when I would go to a city or a large industrial space, and just how alien it felt. I think I’m still narrowing in on that feeling.”

In 2015, Steele became an artist-in-residence at Goodyear Arts, a nonprofit arts program in Charlotte. This allowed him to further explore that feeling and its embodiment in his work, which has been exhibited and collected internationally. Steele and his wife, Susan Jedrzejewski, associate at Charlotte’s Hodges Taylor Gallery and a former codirector of Goodyear Arts, live in a 2,000-square-foot house with a walk-out basement that serves as Steele’s studio. This is where he makes the work that fuels his creativity. “There’s something incredible about waking up and making something,” Steele says, “of walking downstairs and turning on the table saw.” At the end of the day, Steele says, nothing can compare to the satisfaction of that kind of work: “Something can exist that didn’t exist that morning.”

Left: Sundowning, 2021, machine drawing / pen on black Stonehenge, 50 x 92 inches.

Right: Noir no. 2, 2023, walnut, 23-gauge nails, 47 x 73 x 4 inches. Right: Telophase no. 1, 2022, oak and 23-gauge nails, 72 x 24 x 24 inches. Commissions through Hodges Taylor.

Most of the time, that something is made of wood, and usually, that wood is walnut. It’s the wood he first learned to use many years ago when his father brought home a huge supply, and still, no other wood compares. “It’s pretty forgiving,” Steele says. “It has a quality that feels special. I’ve created the deepest relationship with walnut.”

It’s this richly colored, earthy-scented material that forms the work inspired by steel buttresses, by engine components, by industrial infrastructure. To Steele, that paradox points to a larger message. “I remember a thought I had in college about people in the world that we build,” he says. “It’s so easy for us to think of us as separate from nature, but we make our beehives, and we make our own beaver dams. We’re just animals.”

In Charlotte, Steele is making his mark. Last year, he received an Emerging Creators Fellowship from the Arts & Science Council, and he is currently at work on a major piece of City of Charlotte-funded public art that will anchor a streetscape project on J.W. Clay Boulevard in the University City area.

Making public art — which has kept him busy in recent years — is the realization of a long-held goal. In 2019, after a series of rejections for proposals he’d submitted for public art commissions, Steele decided to make a work of art to please himself: “I just thought, Nothing is working. I’m just going to make whatever I want.” He took the form of Greek statue The Winged Victory of Samothrace as inspiration and “depicted that idealized sculpture as this sort of grim, dark oil-covered mess.” The resulting (Nothing is Working) Victory is a metal form that recalls the iconic sculpture’s shape, but is built using intersecting pieces of metal, held up on a wooden trestle. The process taught him to make organic, volumetric shapes he hadn’t been able to create before. A few weeks later, Steele got his first call to make a piece of public art — one that called on his newfound skill.

Left: Basalt Pillars, 2021, walnut, 23-gauge nails, 16 x 48 x 4 inches.

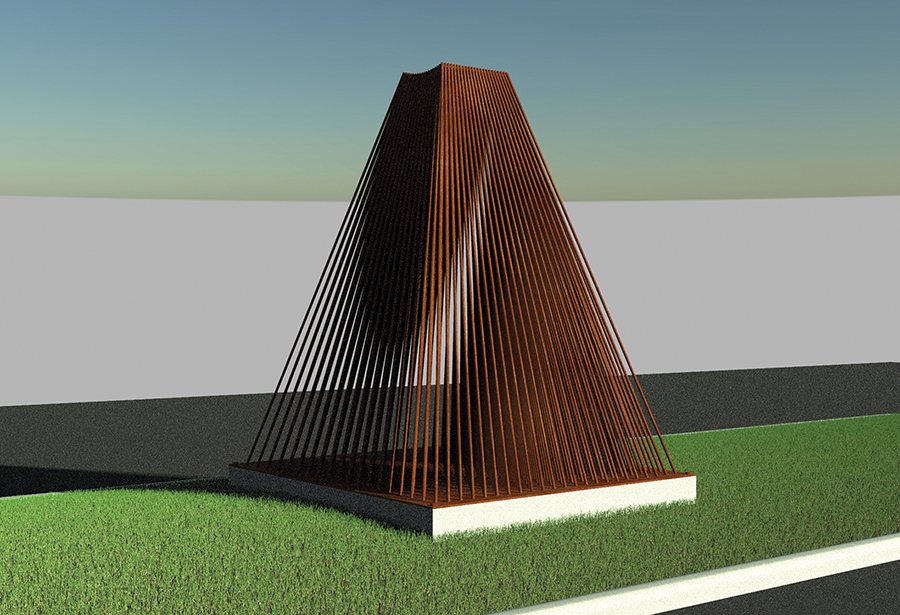

Right: Rendering of Fabric, a city-funded work slated for installation in University City in 2026. Rendering courtesy of Matthew Steele.

Guaranteed funding, a larger scale, a public audience and a sense of permanence make these commissions particularly prized. But the making of a piece of public art can become weighed down in procedure — paperwork and correspondence and engineering — that can remove an artist from the creative process. “It’s a tricky transition,” Steele says. “You’re using new materials, on a completely different scale.”

Schematic depictions of Fabric, the piece he’s currently working on for the City of Charlotte, clearly share the elegance, energy and story of his studio work. Before submitting his proposal for the commission, Steele researched the industrial history of the area and became inspired by the early-1900s textile mills of the NoDa area. “I found old photos from the archives, images of factory rooms with thousands of spools of thread,” he says. “I just couldn’t get over the visual, all of these threads coming through.”

He began to experiment with steel rods and developed the design for what will become a 10-foot-tall, 6-ton piece of steel rods. Slated to be installed in 2026 on a median in J.W. Clay Boulevard, the piece will be a sort of pyramid of rebar, where slivers of daylight will shift with the movement of a viewer.

“Public art is really, really exciting,” he says. “You get to do something you wouldn’t do any other way.” PS

This is an excerpt from Art of the State: Celebrating the Art of North Carolina, published by UNC Press.