Intrepid and fearless, the widow of James Boyd became the unflinching voice of the Sandhills

By Bill Case

In the depths of the Vietnam War, Washington Post owner-publisher Katharine Graham agonized over her decision in 1971 to print the Pentagon Papers. The top-secret Department of Defense study leaked to both the Post and The New York Times established that multiple administrations had misled Congress and the American people regarding the government’s conduct of that war. The Post and Mrs. Graham were threatened with potentially dire consequences if they elected to publish the damning document. Mindful of the threat government retribution could pose to a free press, Graham persisted. Steven Spielberg’s movie about that decision, The Post, starring Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks, will be shown at the Sunrise Theater in February, sponsored by The Pilot.

In the depths of the Vietnam War, Washington Post owner-publisher Katharine Graham agonized over her decision in 1971 to print the Pentagon Papers. The top-secret Department of Defense study leaked to both the Post and The New York Times established that multiple administrations had misled Congress and the American people regarding the government’s conduct of that war. The Post and Mrs. Graham were threatened with potentially dire consequences if they elected to publish the damning document. Mindful of the threat government retribution could pose to a free press, Graham persisted. Steven Spielberg’s movie about that decision, The Post, starring Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks, will be shown at the Sunrise Theater in February, sponsored by The Pilot.

At the time she made her fateful Pentagon Papers decision, Katharine Graham was in her eighth year as the Post’s publisher, having succeeded her talented but troubled husband, Phil Graham, who took his own life in 1963. Though management of the Post was a role Katharine Graham never imagined she would fill, she served that paper with distinction for 29 years and presided over its growth into a media giant.

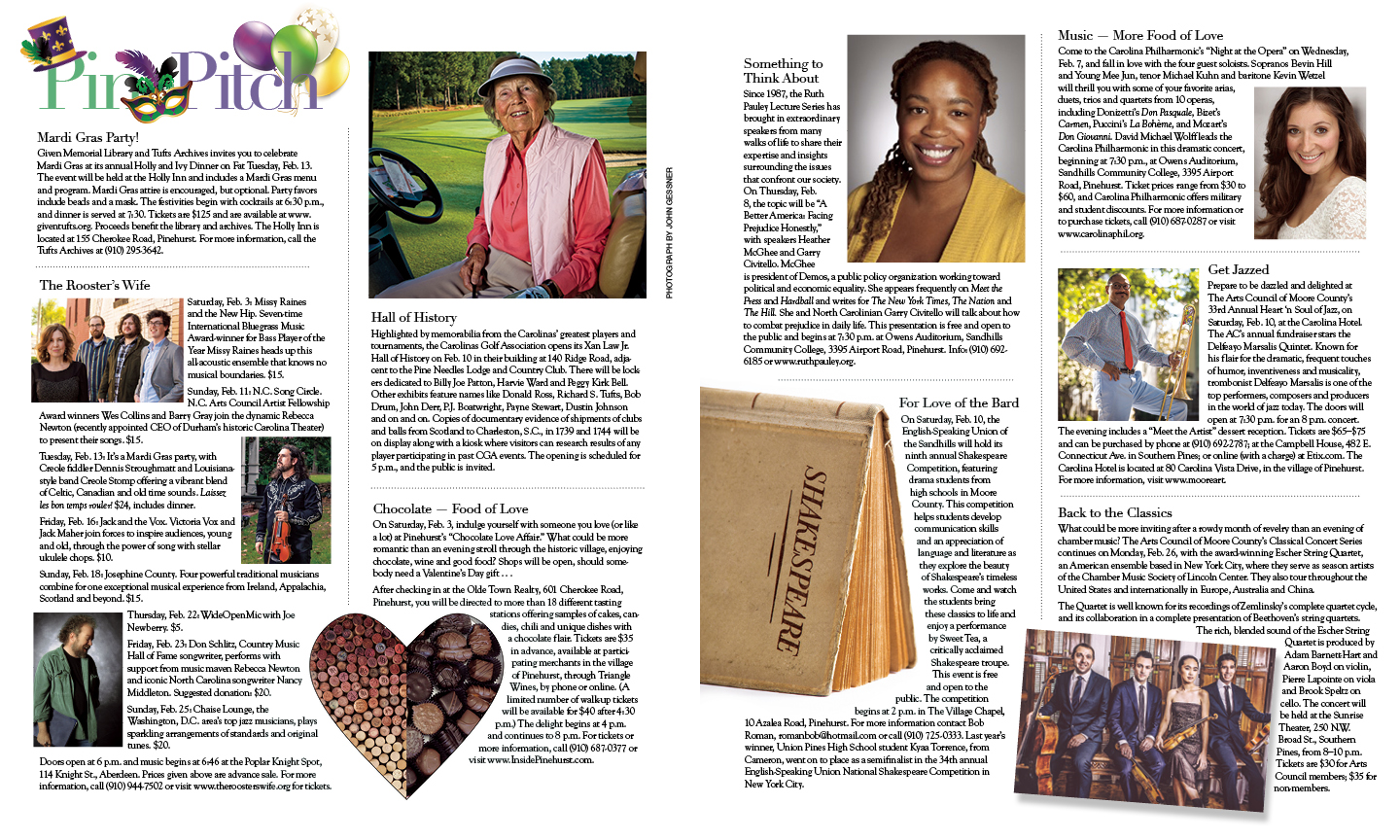

Graham’s ascendancy to the Post’s leadership due to her husband’s demise mirrors, writ large, the experience of another Katharine — Southern Pines’ own Katharine Boyd. In February 1944, her husband of 27 years, 55-year-old James Boyd, The Pilot’s editor and publisher, suffered a fatal cerebral hemorrhage. His death presented a daunting challenge for the patrician daughter of New York tycoon (and Grover Cleveland’s secretary of war) Daniel Lamont.

Prior to James Boyd’s death, Katharine’s primary activities in Southern Pines had involved raising the couple’s three children, riding to the hounds, gardening, and entertaining James’ literary friends like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sherwood Anderson, Thomas Wolfe, Paul Green and Maxwell Perkins at the couple’s home, Weymouth, built by the Boyds in 1922. Her previous writing experience had “consisted of doing editorials one year for the Sandhills Daily News, a small sheet whose fiercely Republican subscribers eventually got fed up with my writing and I was politely fired,” as she later put it. She did, however, have one advantage. Since her husband suffered from writer’s cramp, Katharine often took down his dictation of novels, stories and poems. “My real training in writing was gained through the experience of watching my husband work; learning something of his respect for words and feeling for style. Any facility I . . . acquired is due to him.”

And James Boyd’s style was a first-rate exemplar. During his heyday of 1925 until his death, few could better him, having practically invented the historical novel. His first book, Drums, published when Boyd was 37, became a best-seller and was lauded by reviewers at the time as perhaps the finest novel written about the American Revolution. Boyd authored four other historical novels and numerous short stories for literary magazines. After acquiring The Pilot in 1940, he wrote prodigiously for the paper.

In one respect at least, Katharine Boyd’s new responsibilities at her small-town newspaper were more all-encompassing than those of Katharine Graham at the Washington Post. Boyd now served in the dual roles of publisher and editor, personally contributing columns and editorials to the weekly. She took over writing her deceased husband’s popular “Grains of Sand” column. At first, Katharine could not bear to remove James’ identification as the paper’s publisher from the masthead. Only after the passage of several months did she start listing “Mrs. James Boyd” as publisher. It took another year before the masthead was changed to identify the publisher as “Katharine Boyd.”

New to newspaper work, Katharine adjusted to its unceasing deadlines and the unfamiliar jargon. In her “Grains of Sand” column in 1968 she wrote that the paper’s business manager, Dan Ray, would periodically come to her office with questions that would “send scaredy-cat shivers” down her back. One such inquiry during her first days at The Pilot occurred when Ray asked her, “We’re all set; you got the jumps?”

Katharine indignantly and furiously shouted back, “Of course I’ve got the jumps! I’ve had them ever since I took this job. Talk about jumps — I do nothing but shake.”

Ray guffawed in response, “Are you crazy? Why the ‘jumps’ are the continuations onto other pages.”

Katharine had been on the job for only a few months when she intrepidly waded into turbulent waters with a controversial editorial castigating the Republican Party’s bigwigs after its 1944 convention. The staunch Democrat railed against the GOP’s leaders. “They want to swing America into the role of big business which they themselves personify,” she wrote, thundering on that their leaders’ “imperialistic tendencies, coupled with the propaganda constantly fed our people by the Republican-supported press, are straws in an evil wind.”

There followed a blizzard of protests from readers who were aghast that their local paper was dipping its toes into the thicket of national politics. It was pointedly noted by one reader that the previous editor had confined his political editorials mostly to local issues. Another letter writer argued, “We can get all the politics we need from the BIG CITY DAILIES. Can’t we have our nice home paper free at least from the partisan brand?”

But Katharine Boyd refused to back down. “The policy of The Pilot has not changed,” she responded. “It has always stood for what it considered best in the community and in the nation. It has supported no political party over another except as one or another stood for things, which The Pilot believed. It has tried to represent fairly the great issues of the times and to take a stand on what it considered the right side of those issues. It is the hope of the present editorial board that it may always continue to do so.”

That early brouhaha aside, Boyd learned to love the daily hum of newspaper life. One of the paper’s longtime staffers, Mary Evelyn de Nissoff, reflected that “(I)t was a familiar sight to find her (Katharine) seated on a high stool or standing hunched over the proof-reading desk, her nose pressed against the galleys she held in hands badly crippled by arthritis, proofs of editorials she had written or stories someone else had written. She wanted to know, even though she had another editor or two or three, what was going into her paper.”

Katharine later recalled her biggest thrill on the job came when the newsboys got their papers and rushed to hawk them. “The number of boys — 12 to 20 — stand ready to go as the big moment approaches,” she wrote. “ First the shop people do a football charge, plunging through the crowd with enormous piles of papers in their arms, each pile to go to one of the various stands around town. Then the great moment is here and each boy picks up his pile and off they go, on the run! They swarm out the big high door at the back, run like antelopes around the corner, whooping. They take a deep breath and start to shout ‘PILOT!’”

She also reveled in expressing herself journalistically. Katharine’s first-person accounts of her tours to Scotland and Egypt graced the paper’s pages. Her musings in “Grains of Sand” won awards. She leaped at the chance to travel by train with fellow Democrat Adlai Stevenson during the final swing of his ill-fated 1952 presidential campaign. She filed daily reports of the campaign’s doings with The Pilot. Coincidentally, Katharine Graham later dated Stevenson after her husband’s death. Graham revealed in her autobiography Personal History that Stevenson collapsed and died in 1965 shortly after spending “at least an hour” in her London bedroom, and leaving behind his tie and glasses.

Like Mrs. Graham, Katharine Boyd could not, or would not, sidestep the major controversies of her day. After Southern legislators crafted a document known as the “Southern Manifesto,” urging defiance of the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation decision in 1954, Boyd unhesitatingly condemned the Manifesto, believing that adherence to it would only lead to lack of respect for the rule of law. She applauded the brave decision of local congressman Harold Cooley not to sign it. The Pilot’s editorial page stated, “The sooner the South accepts the fact that the Supreme Court’s decision is lawful under our Constitutional system of long standing, the sooner we will see the current rising tide of emotionalism subside and the sooner we can get on with the work of finding peaceful and reasonable ways of meeting the problems presented by the segregation ruling.”

She became incensed when Birmingham’s police chief turned the hoses and dogs on civil rights marchers. An angry Katharine excoriated Alabama’s governor with this invective: “In refusing to treat the marchers as human beings and as citizens, in encouraging the brutality of the police and the mob spirit of that mountain area, Governor Wallace and those behind him are playing with a fire whose fuel is from the same source that fed the fires of Dachau.”

Mrs. Boyd even criticized North Carolina’s legendary senator Sam Ervin, whom she felt had not done enough to afford access to the ballot for African-American voters. “Senator Ervin knows as well as anyone else that thousands of American citizens are being denied the right to register and vote by unfair, so-called literacy tests, intimidation and subterfuge of one sort or another. Yet here he is using every stratagem to defeat a simple, workable, and fair law to eliminate a situation that is nothing less than a national disgrace.”

Similarly, in expressing her contempt for legislators’ claims that they were simply complying with the wishes of their constituents by opposing federal intervention in the registration of voters, Boyd remarked that these representatives “never seem to consider that Negroes are their constituents too.”

Katharine exhorted local businesses to hire African-Americans and pay them well. She combined practical and moral arguments to make her pitch. “Aside from the economic benefits certain to accrue to any community or area or state which uses its full human potential well, there is a moral issue which can no longer be denied: ‘to give men and women their best chance in life.’ Can any goal be more American than that?”

While the paper flourished during Katharine Boyd’s tenure declining health would force her to sell The Pilot in 1968 to veteran newspaperman Sam Ragan, although she did stay on for a time as a contributor. Ragan, who came to know and admire Mrs. Boyd, later summed her up this way: “Katharine Boyd was both tender and tough-minded in her views and outlook. She was gentle, generous, and gracious, but she could be equally strong against sham and hypocrisy.” Mary Evelyn de Nissoff remembered Boyd as being shy but nonetheless gregarious. “She liked her friends around her, sometimes in masses, as they gathered for her Christmas ‘sings’ in her big, hospitable home, Weymouth, and sometimes, one or two at a time.”

While Katharine Boyd enjoyed an outstanding career at The Pilot, her achievements as its editor and publisher are dwarfed by her acts of philanthropy that continue to enrich the lives of residents of Southern Pines, Moore County and North Carolina. Her unflagging contributions of time and treasure to charitable institutions such as Moore Memorial Hospital, St. Andrews Presbyterian College, Sandhills Community College, the Southern Pines Library, the North Carolina School of the Arts, the North Carolina Symphony, Penick Village and the American Ballet Theatre are unparalleled. Her deeding of 400 acres of wooded land to the State of North Carolina in 1963 for establishment of the Weymouth Woods-Sandhills Nature Preserve provided a permanent refuge for wildlife and a lasting benefit for our environment.

Katharine died in 1974. Her bequest of Weymouth and its surrounding 200 acres for charitable purposes led to the establishment of the Weymouth Center, which supports North Carolina’s writers and recognizes their literary achievements, thereby serving as a lasting tribute to the legacy of both James and Katharine Boyd.

Her friend Jane McPhaul remembers her as a person who provided “advanced leadership” to civic causes despite never having held elective office. Noting her qualities of fearless independence and leadership, McPhaul has always considered Boyd a wonderful role model for women. She recalls her as a person who “stood on her own two feet” in a time when society often expected women to take a backseat.

While their times in charge of their respective newspapers did overlap from 1963 to 1968, it is doubtful that Katharine Boyd and Katharine Graham ever met, though they had much in common. Borne of prominent families, they each leaned in the direction of the Democratic Party, Katherine Boyd more emphatically so. Both relished entertaining friends, including numerous national figures. And despite the enormous disparity in circulation of the two newspapers for which they labored, the two Katharines shared a similar philosophy regarding how papers, of all sizes, should be run. It is a philosophy celebrated in Spielberg’s upcoming movie and captured in the pithy Sam Ragan quote still carried on the editorial page of every edition of The Pilot:

A long time ago, a wise old editor said,

the function of a newspaper

Is “to print the news and raise hell.”

I haven’t been able to improve upon that definition.

-Sam Ragan, Editor and Publisher, 1968-1996 PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.

F

F couple’s enthusiasm, anything goes.

couple’s enthusiasm, anything goes.  Crown moldings? Jenn shakes her head.

Crown moldings? Jenn shakes her head.

Might this be the only home in Pinehurst fielding but one antique — a plain oak sideboard in the dining room, from Eric’s great-aunt?

Might this be the only home in Pinehurst fielding but one antique — a plain oak sideboard in the dining room, from Eric’s great-aunt?