By Bland Simpson

Illustration by Harry Blair

On a green field of order, where I wait

for this game’s random shifts to bring you back,

high and low, striped and solid balls rotate.

I chalk my cue and call for one more rack . . .

— Henry Taylor, from An Afternoon of Pocket Billiards

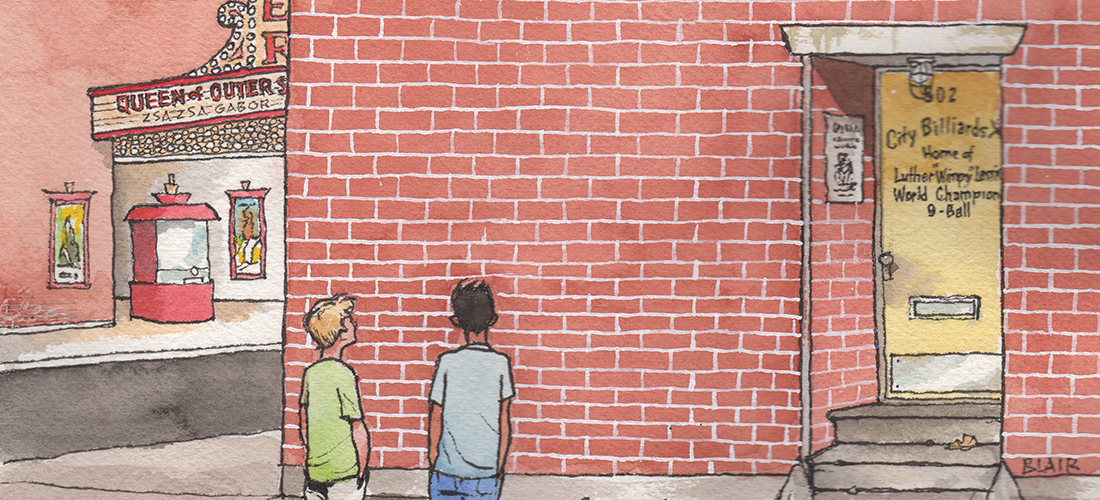

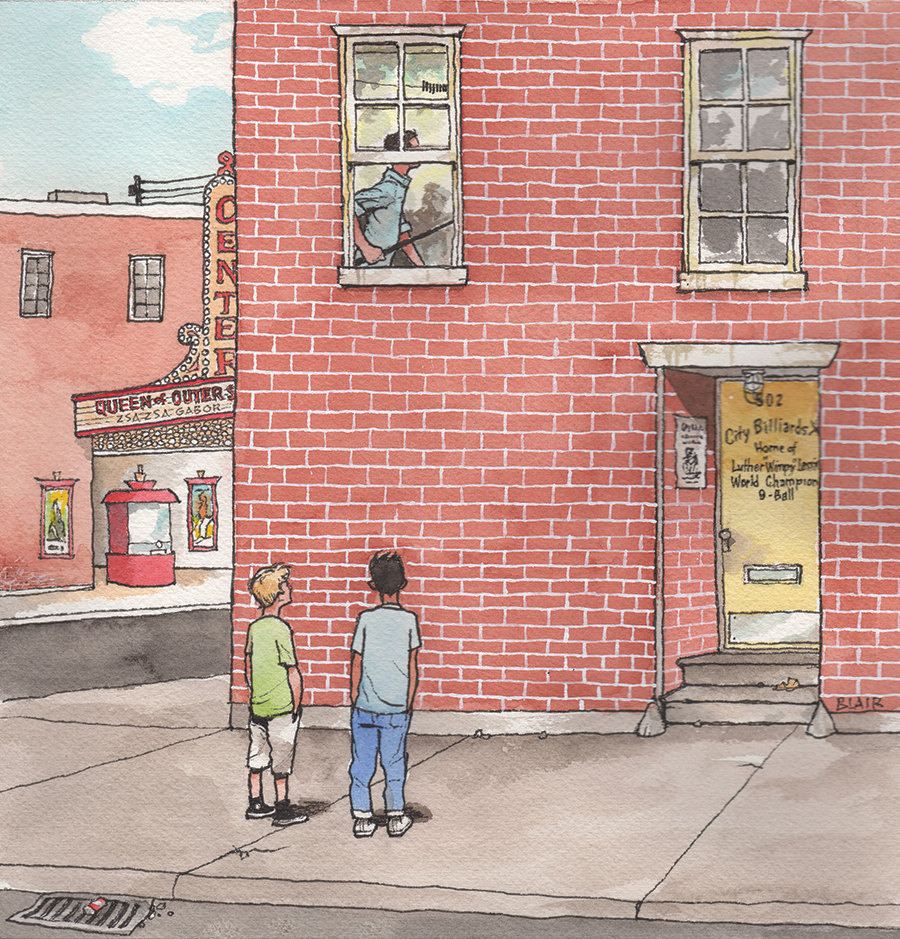

From the open upstairs windows of a plain two-story commercial building overlooking a bricked side-street, Colonial Avenue in Elizabeth City, as a boy I used to hear the pouring out of loud jolly talk and laughter, but most of all the hard clicks of cue balls breaking the racks, and spoken and sometimes shouted encouragements and disappointments, and the lighter clicks of wooden scoring beads, as men I could not see slid them along strung wires above the green felt-covered slate pool tables in that magic room above.

A small sign hung by the street-side door, stating simply: City Billiards, Home of Luther “Wimpy” Lassiter, World Champion, 9-Ball.

In the nearby corner movie theater, the Center, my friends and I often sat, enthralled and forgetting we were only a hundred yards from a swamp river on its way from the Great Dismal Swamp to the sound and the sea, believing instead that we were riding along on horseback as we wove with the cowboys through some saguaro range, or that we were stomping or swinging along with Tarzan of the Jungle through mamba snake-ridden equatorial brakes. We even saw Zsa Zsa Gabor there, in Queen of Outer Space, and knew this short interlude of imaginary galactic travel had brought us to our worshipful knees before the most beautiful and powerful woman in the universe.

Yet when we emerged from these diversions, our riverport reality fell heavily upon us, and the sounds of smack and click kept spilling out from the pool hall on high, and we somehow knew that was where the real men, not boys, went to have their adventures, though all we could do, our ages still in single digits, was to stand on the sidewalk below and listen hard and try and make out what the hoots and hollers and howls, and the cussing were all about, and what they all really meant.

•••

At my Uncle Joe’s home on Greenwood Road, a few hundred yards straight down the Raleigh Road hill below Gimghoul Castle in Chapel Hill, in a large square pine-paneled room stood two grand implements of joy and purpose that guided me through my teenage days: a 1917 player piano, and a Brunswick pool table of more recent vintage with a golden-brown felt top. After school, an inspired fellow could get in an hour of honky-tonk piano playing (Ray Charles’ “What I’d Say,” Floyd Kramer’s “Last Date,” Alan Toussaint’s “Mother-in-Law,” as interpreted by Ernie K-Doe) and another good hour of 8-ball. Even if I were only singing alone and then playing, as well, only against myself. I liked the feel of the ivories, and then I certainly liked the light heft of the cue stick and the faint smell of blue chalk as I squeaked it onto the tip and smacked the cue ball into the rack and heard all that increasingly familiar clack and clatter.

As I could be Ray Charles for a while, then I could be Wimpy Lassiter for a while too. And why not?

Some of my friends from the Greenwood neighborhood, Tom West and Dave Harrison among them, would also chalk a cue with me on occasion, so the progression of lonesome though active afternoons would be broken. After a while, about the time we all turned 16 and could drive (in my case, my uncle gave me the use of a ’48 Willys jeep, with no top and only a seagull feather to dip into the gas tank to discover how close to empty the vehicle was), we decided to take our skills to town and try out a real pool hall, there being one on West Franklin Street and another on West Rosemary Street — said to be somehow under the control of Doug Clark, the musician whose perennially popular band the Hot Nuts toured the East Coast on weekends and played fortunes of off-color R&B music for young college men to alligator to, trying to impress their dates.

So one sunny Saturday morning a quartet of us went into Doug’s pool hall and shot for a couple of hours and, as we knew we would, liked the loud clatter of rack after rack busting apart as ferocious underslung stick action slammed the cue balls forth into battle. That we were white boys in a black men’s redoubt made no difference, or seemed not to. We were no trouble, and we were spending money. We may not have played very well, but we were left alone and did all right there.

We got to going to the Brass Rail pool hall over in downtown Durham, with its clientele as white and laconic as Doug Clark’s was black and passionate. The men of the Brass Rail were low-energy, cynical, worn down from work in the tobacco factories, older men who drifted in and out, playing two or three rounds of 8-ball and drinking two or three longnecks, and some of them hacking and spitting the brown juice of their chaws into bright brass spittoons placed all around the joint.

Our play improved steadily, if slowly, as we visited these emporia, and we played only 8-ball, and my friends found their way to Uncle Joe’s piano and pool hall more frequently as well, so the long lone days had given way to days of what we had come to know as pool hall conviviality. Off to ourselves, we could feign in a way that we were up at Doug Clark’s or over at the Brass Rail and ape the ways grown men walked slowly around with squinted eyes and assayed the lay of a table as they set up their shots, and the ways they addressed the cue ball, maybe lying well over the table as they did, and slammed a long shot home or maybe just barely kissed a combination shot so the second ball in the combo might lightly curl around the cushion corner and fall smartly into the center pocket. We learned that it was not only the shot, but also the next shot, and so we learned about the leave.

And that this was all geometry worth knowing.

What really elevated the importance of pool and rooms in which it was played was a talk with my father one evening, which began with him saying: “We need to talk about where you stand with the draft.”

“The draft?” I had yet to turn 18, and only would during my first term at Carolina.

“What do you know about it? And I don’t mean what you’ve heard around the pool hall — what do you really know?”

Not a long call, but a keen one. I promised I would follow up, check on whatever I would have to do to register, and so forth. But what was truly meaningful was my father’s realistic assumption that I would have, even should have, found my way to the pool hall and heard there the inevitable levity and also serious talk about serious matters and that, also, I might not have known how in the midst of animated and, at times, fur-flying talk, to tell what of it was real and what was not. My father was letting me know, advising me of the truth in a slant way, that one needed, always, to take the temper of the room, to learn extra-well how to navigate the gathering places, the watering holes and oases of the world, to note which assertions had real grains of truth within them and which ones were as flimsy as those thin wires above the pool tables threading through the wooden scoring beads.

He was telling me that a pool hall was a truly important place, and he was right.

For that first one I ever recalled, City Billiards there in Elizabeth City just a couple of blocks from where my father was born and lived and practiced law, and only two miles from where he died, drew many men into its convivial space, many of them rank amateurs, some poseurs with light skills and a trick or two and perhaps a two-bit hustle, and a few truly talented when it came to chalking a cue.

Yet one of them — and only one — was the champion of the world.

•••

In time, my old friend Jake Mills showed me his two favorite pool halls, Happy’s on Cotanche in Greenville, and Wilbur’s on Webb Avenue in Burlington. After school in the 1950s, he and his longtime friend Steve Coley used to play quarter games against the textile mill hands coming off first-shift and drifting into Wilbur’s straight from work. The cigarette haze hung low below the green shades, and the cry of “Rack!” was in the air and the balls clicked and clacked and, like many a youth before them, Jake and Steve picked up pin money in this Alamance County 8-ball haven. When, decades later, Jake and I looked in late one winter’s day, had a cold one, and shot a round, no haze hung, and we were just about the only ones in Wilbur’s as a gloaming crept over the closed mills at half past five.

Once, at the courthouse square pool hall in neighboring Graham, the bartender serving Jake after a spell commiserated with him, telling Jake about his best friend and how the best friend’s wife had recently stabbed him in the back with a Bic pen, not really hurting him, but . . . “Pretty pointed message,” Jake said, and the bartender grimaced. “I mean,” Jake went on, “she must’ve thought he wasn’t exactly seeing the writing on the wall.” At which point the bartender shook his head angrily and walked off.

Sometimes in New York City, fellow songwriter David Olney and I found ourselves in the big, 16-tabled, Upper West Side 79th Street Billiards at the northeast corner of Broadway. The hall had a fortune of windows wrapping around its corner, facing west and south, and so had a bright, airy disposition to it, even on a cloudy day. One slow afternoon, the owner, a stocky man about 60, ambled by as we racked the balls and asked us where we fellows were from. When I said North Carolina, he asked: “Anywhere near Elizabeth City?”

“That’s where I grew up — Luther Lassiter’s from there!” I went on about the Colonial Billiards, about how Lassiter started hanging around there as a boy, got the use of the tables for keeping the place swept up.

“Wimpy — sure. He always comes by here anytime he’s in town, runs the table a few times, shows everybody how you do it. Nice guy. The best.”

“What about Minnesota Fats?” I asked.

“Fats? Aw, he’s a loudmouth, a braggart — he’s nothing but a hustler.”

The pool hall man who had seen it all let that sit a few seconds, nodding at Dave and me both, and just before he walked on through a space that is no more, said with finality: “Wimpy Lassiter’s the best 9-ball player I’ve ever seen. Straight pool too. And on top of that, he’s a real gentleman.”

•••

Semi-dim places like Crunkleton’s in Chapel Hill and the Orange County Social Club in Carrboro featured single tables back away from their front doors, always a nice sight for an 8-ball man or woman. Though a single table hardly a pool hall made, the OCSC, like Neville’s agreeable speakeasy just off Broad Street in Southern Pines with its lone table, seemed at least halfway there. My son Hunter and I were chalking post-Thanksgiving cues not long ago in the OCSC and challenging David and Heidi Perry, and in the ensuing contest across the red felt table (with chalk cubes to match), our energies went betimes vivid, betimes laconic, matching the energy in the small Paris-of-the-Piedmont barroom (“Nice to be channeling the Royal James,” David said a time or two).

In former days, women would not have found such welcome in the real pool halls. Dave Harrison and I brought our dates into the Brass Rail in Durham one evening after we had gone to an art film at the Rialto and for that integrative act earned just about the most brazen, hostile glares either of us had ever received. But that age went by the boards sometime as the 20th century aged and passed on, and pool tables started showing up, along with darts and foosball games, in many a spot that served wine as well as beer. Vic’s smoky tavern on Turner Street in Beaufort (where, my wife, Ann, has told me, a young woman’s reputation would be shot should she ever enter) kept its three big, beckoning, green-felt slate tables and became the Royal James, smoky no more yet still and all one of the best pool halls in the land and a renowned epicenter of eastern Carolina-ness, welcoming all comers and losing nothing in the bargain.

Channeling the Royal James indeed.

I have sat in the Royal James, the RJ, on a Thanksgiving-tide afternoon and heard the best of talk from Steve Desper, the late impressive science educator, about speculative ways to pull nitrogen out of the Neuse River; have heard from author Barbara Garrity-Blake of an African American menhaden fisherman engaging the captain of the pogeyboat upon which they both worked in there and telling him, movingly, “I know why you fish, Cap’n, ’cause it’s in your heart”; seen a laughing female in a sequined, formfitting camouflage dress pulling the taps behind the bar at a blistering pace one Friday night; seen another woman polish off male 8-ball opponents on the middle slate table just as fast as they could challenge her, she in all respects untouchable; and seen families of every imaginable age range taking a few moments off the baking summertime Beaufort streets and cooling out on the smaller, 75-cent tables in the back of the hall.

And over a stretch of 35 years I have found the Royal James to be as good a barometer of balance as any around, and far better than most. As much as I have enjoyed concertizing in theaters great and small around the world, or spending serious time in the corridors of power and the halls of academia, I have also learned that a man without time to enter the pool hall and find a pint of hops and chalk a cue and go two out of three or three out of five with a handful of friends is a man missing out on some of life’s best essences. For X marks the spot where geometry and conviviality cross and create the billiard parlor, the pool room, and praise be for such salubrious intersection.

At home in the hill country of Carolina, I once unwrapped a present from Ann and our daughter Cary, a lightweight something in a 2-by-3-foot box that turned out to be a miniature pool table replete with 3-foot cue-sticks and inch-and-a-half balls. And a full-sized cube of chalk.

Its name — with no shadow falling between contemplation and act — immediately became the Royal James Jr. And over many years since its unwrapping, upon its green felt in our red-clay country living room, many a family and friends contest of geometry and will has been launched, played with an exacting hilarity, and settled. The relish to rack is the same, the squeak of the chalk the same, and much is spoken and heard around the RJ Jr. pool hall.

And the smack and click of the white cue and the striped and solid balls are the same as they ever were, just as those clear sharp convincing sounds were when they leapt out the windows and echoed over Colonial Avenue and rained down on us boys there, emanating from Wimpy’s home court, City Billiards of long ago, where up the same lopsided stairs in the same second-story room near the banks of the Pasquotank River, there is a pool hall yet. PS

Bland Simpson is Kenan Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, the author of nine books and a longtime pianist and composer/lyricist for the Tony Award-winning North Carolina string band The Red Clay Ramblers. In 2005 he received the North Carolina Award for Fine Arts.