A proud Southern couple furnishes their house with family history

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Gessner

Family means everything to Mary Balfour Dunlap and her husband, Murray Dunlap. Mary Balfour grew up alongside grandparents, aunts and uncles. “My cousin is like a sister. Family is who we are.” These roots run deep in Mississippi, where Mary Balfour’s father, a cotton farmer, became an Episcopal priest. The Balfour in her given name honors a great aunt. Portraits hanging from her walls represent ancestors. Murray — a lauded writer, poet and artist — is from Alabama, where Mary Balfour later lived and worked. His background also included old, beautiful Southern things. Nowhere do their heritages blend better than in a simple yet charming brick bungalow where furniture, paintings, carpets, silver and china hum the same tune.

“We didn’t buy one single piece of furniture. My dad and mom and Murray’s dad were collectors,” Mary Balfour says. Coincidentally, their parents were downsizing. Just imagine, if these tables and chairs, sofas and bureaus could speak of the people, places and events they have witnessed.

No need. Mary Balfour (“I’m the talker, Murray’s the introvert”) serves as docent.

“Murray flew me to Mobile for our first date,” she begins. They had never met, only talked and corresponded. Once there, she recognized a kindred spirit. “I saw his house . . . I was drawn to his art.” The tall blonde with wide smile was attending seminary in Austin, Texas, fulfilling a vocation that came after working as a fundraiser in Washington, D.C., and Birmingham. Murray, who holds an Master of Arts in creative writing from the University of California at Davis, had survived a catastrophic car crash in 2008 that left him in a coma for three months, then wheelchair-bound with traumatic brain injury and memory loss. His progress, although slow and arduous, has been dramatic. Murray mows the lawn, tends the garden as well as creating abstract/modern art — and publishing a book. He has been selected as writer-in-residence for November at Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities.

They married in 2015. Murray works from home. Therefore, where to settle was Mary Balfour’s decision.

“If we can’t be near family, we want to be near good friends,” she says.

A position as associate rector opened up at Emmanuel Episcopal Church in Southern Pines. Close friends from Birmingham, Elizabeth and John Oettinger, lived here. Mary Balfour accepted, then tasked Elizabeth with finding a rental house, preferably in Southern Pines, where the church was located. The friends had similar tastes. Choices, however, were limited. “I looked for a place where I would consider living,” Elizabeth says. She investigated a post on Instagram, forwarded photos to Mary Balfour and Murray, who took it on faith.

“I saw the picture of the mantelpiece and could imagine Daddy’s portrait over it,” Mary Balfour says. “I knew I could keep my china and silver, which we use every day, in the (built-in) corner cupboard.” The clincher was a sunny side porch enclosed as a den, where Murray could write — also, an outbuilding which now houses his painting studio.

In October 2016, they moved into their first shared home.

This brick quasi-ranch built in the early 1950s on an oversized treed lot escapes the stereotype via paned bay windows and a small, uncovered front porch with white railing and two enormous Boston ferns flanking the blue door. Off to the right, a cottage furnished in less-formal antiques serves as guest quarters.

Once inside the house, a predictable floor plan is eclipsed by pieces from comfortable, much larger Mississippi Delta homes, circa early 20th century. The living room armoire was made by slaves: “Not a screw in it except for hinges,” Mary Balfour points out. The walnut “secretary” (drop-leaf desk) belonged to Aunt Balfour.

The living room settee (definitely not a couch or sofa) framed in carved wood is upholstered in pale avocado, the colors drawn from Persian carpets worn threadbare and mended by Mary Balfour’s mother. Artwork, including several Dali drawings, are framed and grouped artistically. “Murray has the eye,” his wife learned. His black and white landscape photos make up part of the gallery. Mary Balfour calls two side chairs reminiscent of a medieval castle her “bishop’s chairs” since a Costa Rican bishop stayed at Owen’s Place, the guest house named after their beloved dog, recently deceased. A pair of Cavalier King Charles spaniel china figurines have been retrofitted as lamps and placed on the sideboard underneath a portrait of Murray’s namesake ancestor.

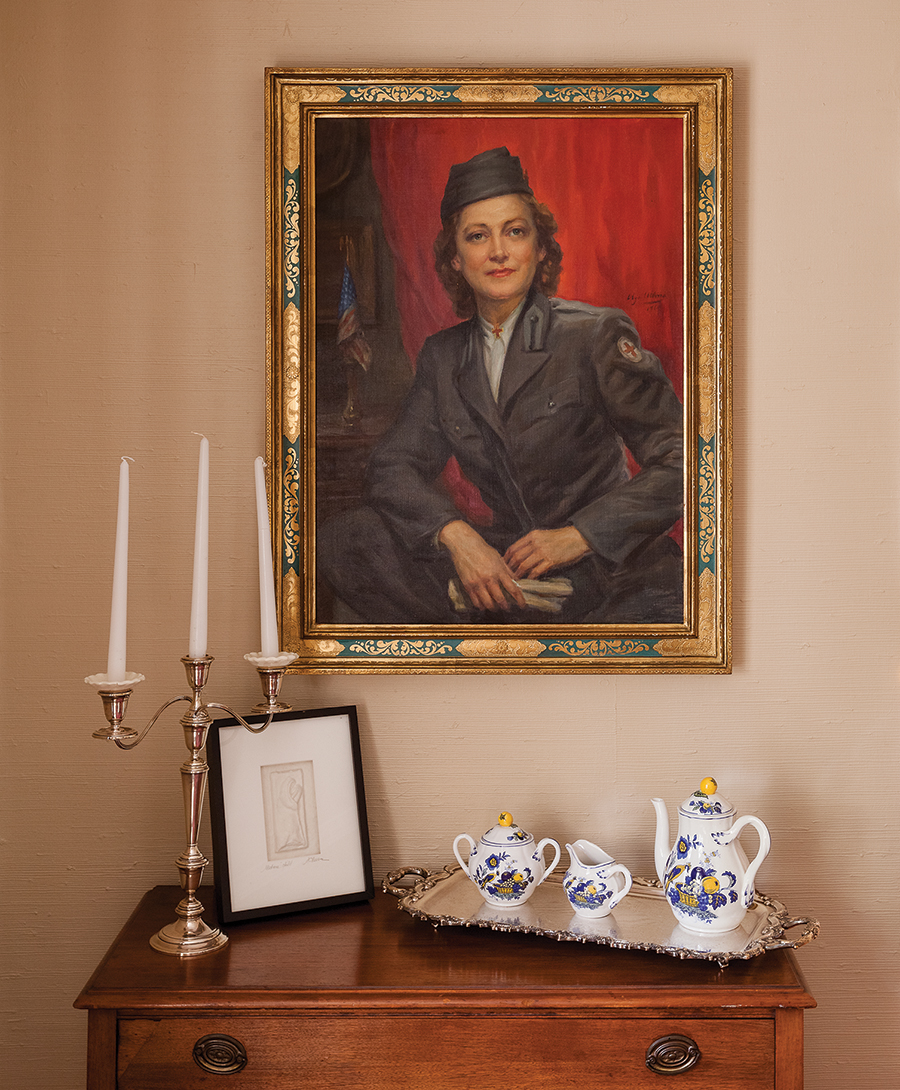

Two other portraits dominate the living-dining space: Mary Balfour’s grandmother in a Red Cross uniform, the other of her grandfather, also in uniform, both painted in Italy during the 1940s — a coincidence, since they did not meet and marry until after the war.

Another, of a great-grandmother, illustrates the romantic Gilded Age genre.

Delight is in the details. A collection of snuffboxes sits on a silver tray on the coffee table, exactly as it did in Mississippi. Crosses made from steel drums were acquired on a mission to Haiti. And tags with notes written by a grandmother hang from exquisitely wrought silver serving pieces which Mary Balfour keeps polished.

Along a narrow hallway lined with family crests, two of the three bedrooms contain tall, heavy four-posters, one requiring a stepstool, which, even in modestly sized rooms look comfortable, since other pieces are small and simple. The master bedroom furniture recreates Mary Balfour’s parents’ room exactly, including the prie dieu, but not an Indiana Jones hat perched on a post, recalling Murray’s fishing trip to Montana. Mary Balfour especially favors a guest room wall where hang three generations of wedding photos, including her own, and names engraved on a Tiffany wedding cup.

But not all is as expected. Instead of traditional Southern rose, spring green and tepid blue, Mary Balfour chose a pale khaki for the parlor walls and festive cranberry and olive for upholstery. Florals, another Southern décor staple, are scarce except on a wing chair and heavy, dark, crewel-stitched dining room curtains, from Mexico.

The kitchen, of course, had been redone — not overdone — with black countertops, a bar-island, butler’s cupboard, stainless appliances. The original carpenter-made wooden cabinets remain, painted white. “This is our most comfortable room,” Murray says. Here, Mary Balfour accessorized with a breezy contemporary touch, including a glass bubble lighting fixture, bright rooster posters from New Orleans and McCarty art pottery — the Mississippi equivalent of Seagrove.

“We live in the den,” adjacent to the kitchen, Mary Balfour confesses. This is Murray’s domain and repository for chairs, bookshelves, a wooden storage box made by his grandfather and a dry sink, most from his childhood homes, as well as his books and a progression of art work; Man with a Beard, painted before the auto accident, is Mary Balfour’s favorite. “I didn’t know him then. His painting has changed. This gives me a glimpse into who he was.”

What was — along with artifacts conveying a bygone lifestyle — remains central to the lives of this handsome, interesting couple. Their home accommodates an Ugly Christmas Sweater church party as easily as a literary gathering or supper for a few friends. Conversation never lags as Mary Balfour enthralls newcomers with background on their furnishings. She has already begun thinking about the future, how best to preserve and distribute family treasures along with their histories to cousins, nieces and nephews. For now, they are used, enjoyed and safe. Because, as Mary Balfour says, “We are the keepers.” PS