The art of working with stained glass

By Jenna Biter

Photographs by John Gessner

An oversized sheet of white craft paper unrolls across the worktable. “So, what I do,” Sarah Cawn says, her voice trailing off, distracted by a half-open box. “This is a big lamp I’m supposed to repair.” She lifts a cardboard flap and fingers the dome of a Tiffany-style glass shade.

“OK,” she says, gathering herself to explain the process of making beautiful things with stained glass. “This one I just finished.” She points to a drawing on unfurled paper. The contours of wavy-edged poppies and their swan-like stems arc through rectangles configured like the eight windowpanes they represent.

A gilded light casts itself across the drawing. Cawn points at the studio ceiling. “When we built the house, I had the builder box up the skylight so I could put that in there,” she says, her head tipped back. Above her a glass cupola of yellows and browns, trimmed in a filigree of rose and sea foam, warms the drawing below, willing it from the second dimension into the third.

Each section of the drawing, from the size of a button to the palm of a hand, whether it represents a petal, stem or sliver of background, wears a number as its name tag, all the way through 332, like a grown-up’s paint-by-number.

Cawn starts with the obvious. “I roll paper out and cut off as long a piece as I need.” She traces an index finger around each rectangle. “I had already drawn out the perimeters of each window, then put it up over there.” She points to a blank wall on the far side of the studio, half hidden by a table crowded with a collection of glass baubles: iridescent charms reminiscent of abalone, an amber chest overgrown with irises, a heart-shaped box, stacks of colored glass sheets, and a retro lampshade turned on its head.

She plucks the heart-shaped box from the menagerie like a client perusing the wares at a fine arts bazaar. “This is something that I inherited from somebody that got out of the business,” she says, holding the red vessel up to the light. “I thought if I fixed it, maybe I could — I don’t know.” Cawn turns the box over in her hand and inspects the soldering. She wrinkles her nose.

“It looks kinds of crummy, though. I don’t really want to sell it, so I probably should just junk it.” She sets the box down. “I just don’t feel right about selling something that isn’t mine.”

Cawn thumbs through colored glass sheets as if they’re playing cards, and she’s searching for the right one to start building a hand. Clack, clack. Each glass sheet is a different color, striated like the hard insides of a geode. Clack. There are emeralds and milky jades, electric blues and smoky blacks. One sheet is a galaxy of amethyst and mulberry; another swirls angrily like the eye of Jupiter, but in the soft nudes of a conch shell’s aperture.

“I thought it would be fun if I put them together like a patchwork and make cool wall hangings,” she rearranges the pieces like they’re quilt squares, thinking out loud, “if I do the colors right.”

A scarlet macaw perched at the opposite end of the studio stares past Cawn at the half-hidden wall. The bird isn’t real — Cawn made it of glass — but it occupies the space of a live macaw, giving the impression, from the periphery, that it might squawk in its own colorful language.

She points back to the wall where she has tacked up the paper and penciled in the poppy design. “I’m going to be honest now, for the poppies — I do have an overhead.” She describes adjusting the projector until the blooms cast onto the paper create a convincing field of flowers, then she traces the pencil lines with black marker to finalize the design.

Cawn began making stained glass 40 years ago, give or take, at a Maryland shop (whose name she can’t remember and which has since closed) and has, ever since, been polishing her process as if it was, itself, a panel of stained glass.

“For me, it was like a drug,” she says with a shrug. “My husband made me a little workbench down in the basement and, at 10 o’clock at night, he’d go, ‘Are you coming to bed?’”

Through their moves to California, then throughout the Research Triangle in North Carolina, Cawn packed up her glass and tools — marked with a band of cheetah-print tape — and taken her craft with her.

In San Ramon, California, her studio was half the garage. “In the wintertime, I’d have to keep the big glass pieces in the house, so they’d be warm,” she says, explaining that glass can shatter when its temperature rapidly rises or falls.

When the Cawns moved to Cary in the early ’90s, Sarah got her first real studio, but it was on the third floor. She crosses her eyes and groans, “Ughhhhhh,” imagining herself carrying sheets of heavy glass up three flights of stairs. They built their current house, a stone hideaway tucked into the woods just outside of downtown Raleigh, in 1996, and Cawn’s studio is a bonus room above, not in, the garage. An arched windowpane of wispy lines and pastel orbs over the front door welcomes guests into their home and silently announces the workshop upstairs.

“It started here,” Cawn says of her business, Sarah’s Glass Art, taking off. “In the ’90s everybody wanted stained-glass windows above their bathtub or around their door.” She grins sheepishly. “If I was lucky, they did both.”

Stained glass, and the inspiration for it, infuses the property like a visual perfume. Outside, in the backyard, tangerine, fiery red and pale pink koi glint like glass shards in the afternoon sun as they circle an ornamental pond. One fish resembling a golden dragon, with his trailing whiskers and billowing fins, swims near the surface, as if it were a water-bound Icarus waiting to be immortalized in glass like the scarlet macaw.

Later, the Cawns built a second studio, this one detached from the house, where Sarah makes fused glass, a craft she picked up two decades ago. It’s also where she teaches students to work with stained glass, something she started last year.

With the poppy pattern complete, Cawn traces a copy. “Some people take it to Kinkos, or some place that will copy it, but I don’t know how accurate that will be, so I’ve just never done that,” she says. “And I know, I’ve been told, ‘You’d save yourself a lot of time.’” She waggles an index finger. But why fix what’s not broken?

Keeping the original pattern as a template, she fits a jig — a device reminiscent of a picture frame — around the drawn windowpanes and fixes the jig to the worktable. It is the stage where all the pieces will come together. “Nothing’s going to turn out square if you don’t put a border around it,” she says. “If it’s not square, it will look like crap.”

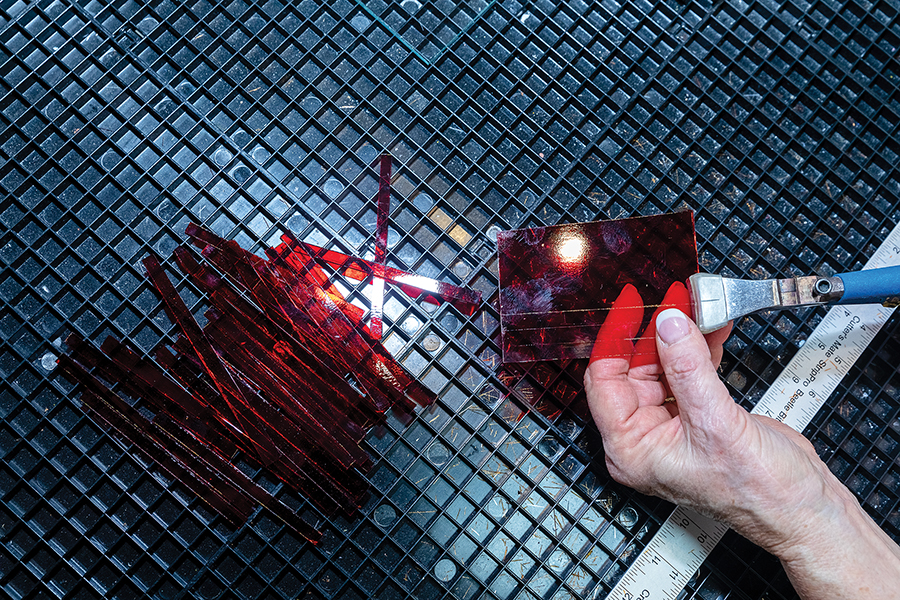

Cawn cuts apart the copied pattern so she can trace each piece of the design onto glass (black marker on light colors and silver marker on darks), then she cuts the glass itself. To demonstrate, she pretends to trace a shape onto a spare sheet of emerald glass, the color she used for the poppy stems.

Cawn looks up as a schnauzer tears around the corner into the studio, nails clacking against the hardwood floor, legs spinning out. “She’s not really cute because she’s shaved now,” says Cawn, apologizing for Schatzi’s shorn summer coat. She reaches down to pat the gray head. “She’s gotten really finicky, so I say, ‘Just shave her. It’s not a fashion show.’” The 13-year-old dog wiggles her stubby tail, then retreats to a plush bed in the corner.

“OK, they’re all cut out, and they all fit nicely,” Cawn says, back behind the worktable. She pulls out a spool of copper foil tape and demonstrates lining the edges of cut glass. “You do this all the way around the glass, and you overlap it by a 1/4 inch at the end.”

Cawn smooths the foil, so the entire edge is neatly covered, and a thin line of copper shows on the face and back sides of the glass. The dark patina of the copper will give the stained glass its signature edge. “You do this on all your pieces,” Cawn says. In this case, all 332.

Soldering comes next, then the patina, then a wax and polish to shine the panel. “You take your wax, shake it, pour a little on, wipe it all over, let it dry, and then you buff it with a rag, and you’re done.” She tosses a rag on the table.

“I used to hate waxing and polishing, but it’s such an important part. It’s the finishing touch, and they go, ‘Ohhhhhhh.’” Cawn puts her hands to her cheeks and opens her mouth, mimicking happy customers and, in a way, herself. “To me, there’s just a magical quality about glass.” PS

Shop for Sarah Cawn’s glass art at One of a Kind Gallery, in Pinehurst.

Jenna Biter is a writer and military wife in the Sandhills. She can be reached at jennabiter@protonmail.com.