Bigger Than a Saltbox

How a second story walk-up became an institution

By D.G. Martin

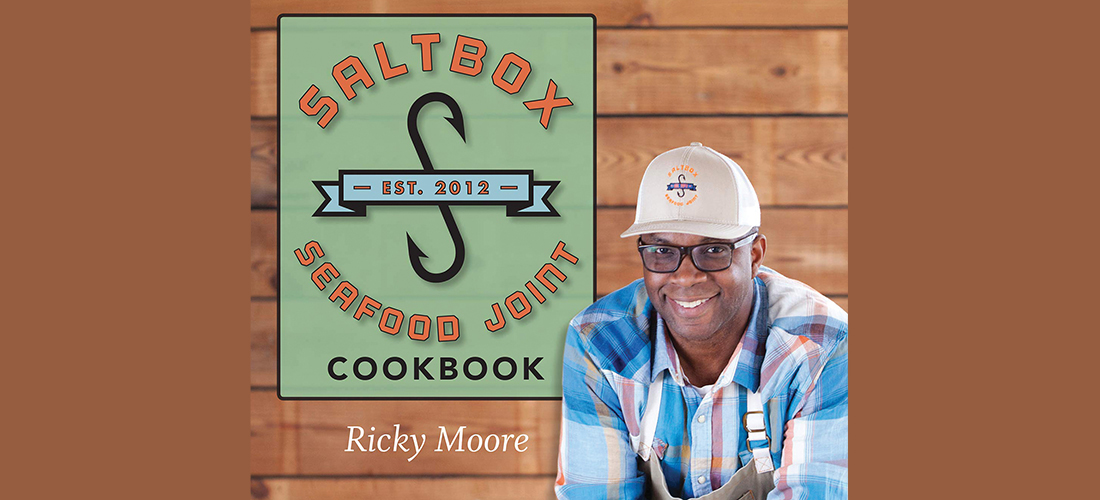

Ricky Moore’s Saltbox Seafood Joint Cookbook is full of good directions and advice about how to select, prepare and serve seasonal seafood from the North Carolina coast. It is also, and primarily, a memoir that explains the raging success of a seafood joint located in a shack in downtown Durham.

It was the delicious food at the Saltbox Seafood Joint that led the University of North Carolina Press to encourage Moore to write a book about the tricky business of getting the best tasting seafood to the table.

North Carolina’s cultural icon, David Cecelski, author of A Historian’s Coast: Adventures into the Tidewater Past, praises the new book as highly as he does the restaurant: “I think he’s written the finest seafood cookbook you’ve ever seen.”

Moore shares 60 favorite recipes and his techniques for selecting, preparing, cooking and serving North Carolina seafood. But the heart of this book is the story of how Moore rose from a hard-working family in coastal North Carolina and used the experiences of his youth, his military service, an education at the country’s leading college for chefs, and work in the kitchens of some of the best restaurants in the world to make a tiny seafood restaurant into one of the country’s most admired eateries.

The story begins near New Bern, where the families of Moore’s mother and father lived.

“I grew up along the Neuse and Trent rivers and spent plenty of my childhood fishing those waters, but I don’t want this to sound as though we were eating fish all the time. We ate it whenever we could get it, whenever it was available, or whenever somebody went out fishing,” Moore writes.

Moore was a self-described “Army brat.” He spent time in Germany and remembered his German babysitter feeding him local raspberries picked that day and freshly baked bread slathered with butter. “There I was, a little kid with an Afro and an orange Fat Albert shirt, soaking up all the German food culture,” he says.

After high school he considered studying art at East Carolina, but he craved the kind of experiences he’d found in Germany. When he turned 18 in 1987, he enlisted. After basic training and jump school, it was time for advanced training. “I picked the first option that would get me out of New Bern: military cook school in Fort Jackson, South Carolina!”

He learned that meals “had to sustain, had to be wholesome, and had to feed a lot of people.” There were regulations and recipes for everything, “even for Kool-Aid.” He learned “how to scale a recipe for a crowd, how to measure, and how to cook in huge vessels and vats.”

As he transferred from one post to the next — from Fort Polk, Louisiana, to Schofield Barracks in Hawaii — he learned new styles of food peculiar to that region. In Hawaii, he met his future wife, Norma.

Just before leaving the Army, an officer told Moore about the Culinary Institute of America, known in the cooking world as the Harvard University of culinary education. In 1993, he enrolled in a two-year program at the Institute and quickly found that, while there was much to learn, his background helped tie the pieces together.

“My basic training as a soldier wasn’t so different from learning kitchen fundamentals, but in culinary school you get the bonus of learning about wine pairings and the practical economics of running a restaurant kitchen,” he says. He interned at the finest nearby restaurants such as Daniel in Manhattan and the Westchester Country Club in Rye, New York. “I went where I needed to in order to learn as much as I could. My goal was to be a great chef, period.”

After the Culinary Institute, he “hopped from one exciting kitchen to another, working with all kinds of cuisines.” He worked for free in the best restaurants in France.

“Through this work abroad, I found a shared sense of tradition, culture, behavior, and, most important, discipline when it came to food and dining. I was the only person of color in these European kitchens, which made me even more intense about learning as much as possible. Being Black automatically pigeonholed you.”

He writes that “the rustic roots of these culinary mainstays weren’t that different from the food of my childhood. I began to see that Southern food is not a lesser cuisine, and I shed many of the insecurities I had held about my own food culture. It was time to head back to the States.”

After returning to the U.S. and working in executive chef positions in Chicago and Washington, he and Norma moved back to North Carolina and settled in Chapel Hill. One day Norma asked him where she could get a fish sandwich. But not just any fish sandwich. A real fish sandwich. A sandwich, Moore writes, “with local fish, lightly breaded and seasoned, fried in fresh oil until golden brown and delicious, then served on fresh slices of yeasty sweet bread and garnished with traditional cooked green pepper and spicy onion relish plus tartar sauce chock full of capers, cornichons, eggs, and herbs.”

Moore knew he could make it — if he could find a good place to work.

He began to look for the right location in Durham. “I wanted a little shop, to do one thing really well, and to control every aspect of it. This was ultimately the base of my business model.”

He wanted Saltbox to be something like the old Rathskeller had been in Chapel Hill, a place folks would consider part of their hometown, a piece woven into the fabric of the community — a place that would make folks say, “You ain’t been to Durham if you haven’t been to Saltbox.”

He found that place on North Mangum Street in the middle of downtown Durham. It was “a little walk-up with the right bones.” By October 2012 he had it ready to open, “just in time for the first fish running of the fall.”

Today, that little walk-up is firmly established as a must-visit. Recently, Moore found a larger place on Durham-Chapel Hill Boulevard, which has turned into a seamless second version of Saltbox, giving folks visiting Durham — and readers of his book — another option to join David Cecelski in swooning about Ricky Moore’s seafood. PS

D.G. Martin hosts North Carolina Bookwatch Sunday at 3:30 p.m. and Tuesday at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV.