Mountain Men

One exceptional life in politics, another in music

By D.G. Martin

In 58-5, two North Carolina mountain boys graduated from local high schools, made their ways to college, and then went on to very different high-profile careers.

Rufus Edmisten moved from Watauga High School in Boone to UNC-Chapel Hill, headed for a career in politics. Joseph Robinson left Lenoir High School for Davidson College on his way to musical performances at the highest level.

Coincidentally, both men recently published memoirs that show how the combination of hard work, high ambition, audacity and luck can lead to success.

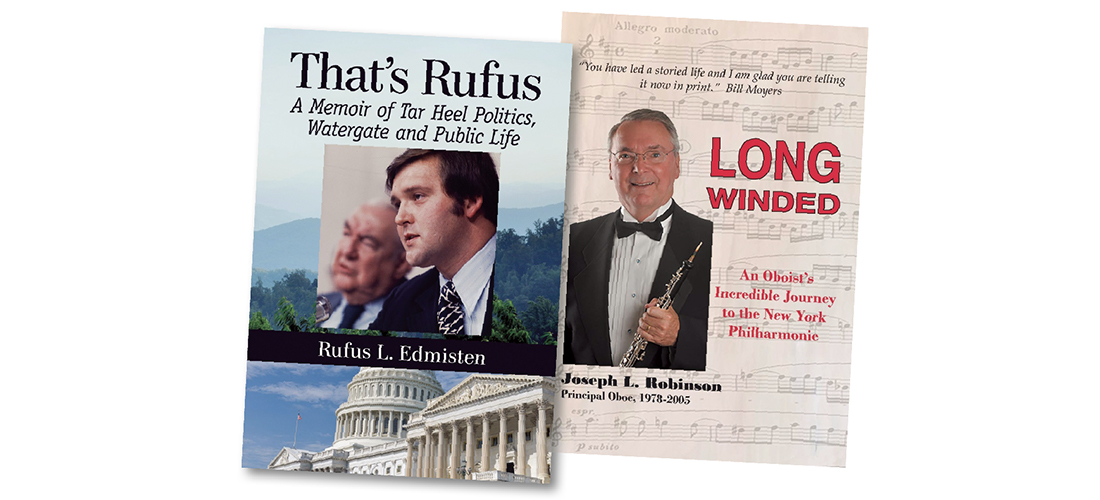

Edmisten’s That’s Rufus: A Memoir of Tar Heel Politics, Watergate and Public Life describes how he grew up on a farm near Boone, tending cows and pigs, and working fields of cabbages and tobacco. After Chapel Hill and a round of teaching high school in Washington, Edmisten entered law school at The George Washington University and secured a low-level job on Sen. Sam Ervin’s staff. He soon became one of the senator’s full-time trusted assistants in the Watergate-Nixon impeachment matter.

His book’s opening pages take readers to July 23, 1973, when he served President Richard Nixon with a demand for Watergate-related records. This key moment ultimately led to Nixon’s resignation under the threat of impeachment and was a launch pad for Edmisten’s political career.

Edmisten returned to North Carolina in 1974 and mounted a successful campaign for attorney general. His triumph over a host of prominent Democrats gave notice he would run for governor someday.

That day came in 1984, when Gov. Jim Hunt ran for the U.S. Senate, and a host of Democrats lined up to run for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination. Edmisten won in a brutal primary runoff against former Charlotte Mayor Eddie Knox and then lost the general election to the then-Congressman Jim Martin.

Some believe he lost, in part at least, because he made disparaging remarks about barbecue. His version of that incident is, by itself, worth the price of the book. But Edmisten says it was Ronald Reagan’s “sticky coattails” that “swept both me and Jim Hunt away from our dreams. We were not alone, either. The sweep was broad and far reaching.”

After the loss, Edmisten felt crestfallen and abandoned. “The ache in the bottom of my stomach was so great nothing appealed to me except finding some dark place to crawl away and hide,” he writes. “I swear I saw people cross the street so they wouldn’t have to talk to me.”

However, he came back from that defeat and won election as secretary of state. How he then lost that position in disgrace and the lessons learned from that sad story make for the most poignant part of the book.

His situation came to a head in 1995. A report by the state auditor and articles in the Raleigh News & Observer alleged the misuse of employees and a state car, abuses by subordinates, and improper hiring practices.

In this deluge of criticism, Edmisten announced he would not run for re-election and, he writes, “I actually thanked God my daddy had died before this mess started.”

Why did it happen?

In a chapter titled “Hubris,” he confesses, “It was nobody’s fault but my own.”

Edmisten writes that it was the excessive pride that arose from his long years at the center of public attention that led to his troubles. He warns, “Once hubris gets a foothold it grows incrementally and accelerates until it is expanding exponentially, and in leaps and bounds takes over.”

This lesson about the dangers of hubris is not the end of the story. In inspiring chapters, Edmisten chronicles how his wife and friends led him back into the practice of law and other areas of service. His wife told him, “We are not going to whine.”

“At the age of fifty-five,” he writes, “I put aside all petty things and began a new life.”

In his new life, Edmisten lives in Raleigh practicing law and giving gardening advice on a weekly radio show. He gives us another lesson: It is never too late to turn an old life into a new one.

Robinson’s memoir, Long Winded: An Oboist’s Incredible Journey to the New York Philharmonic, asks: How did a small-town boy who never attended conservatory persuade one of the world’s greatest conductors, Zubin Mehta, to give him a chance at one of the world’s most coveted positions in the New York Philharmonic, one of the world’s greatest orchestras?

Growing up in a small North Carolina town like Lenoir might not seem to be the best background for an aspiring classical musician. But the mountain furniture community had the best high school band in the state. When Robinson was drafted to fill an empty oboe slot, his course was set.

He loved the oboe so much that his Davidson College classmates called him “Oboe Joe.” However, Davidson’s musical program lacked the professional music training that Robinson craved. Nevertheless, he stayed at Davidson, majoring in English, economics and the liberal arts. His focus on writing and expression gave him tools to win a music position at the highest level.

His success at Davidson led to a Fulbright grant to study in Europe and the opportunity to meet Marcel Tabuteau, who, Robinson says, was the greatest player and oboe pedagogue of the 20th century. When Tabuteau learned that Robinson was an English major and a good writer who could help write his book on oboe theory, he agreed to give him oboe instruction. Those five weeks with Tabuteau, Robinson says, “more than compensated for the conservatory training I did not receive.”

Years later, however, after moving through a series of journeyman teaching and performing positions at the Atlanta Symphony, the North Carolina School of the Arts, and the University of Maryland, Robinson still had not achieved his aspiration to land a first oboe chair in a major orchestra, but he did not give up.

When Harold Gomberg, the acclaimed lead oboe of the New York Philharmonic, retired, Robinson audaciously applied. When finally granted an audition, he prepared endlessly. He was ready for the hour and 20 minutes of paces the audition committee demanded. Afterward, he was confident that he had done very well.

But the Philharmonic’s personnel manager, James Chambers, after saying how well the audition went, reported that music director Zubin Mehta judged Robinson’s tone “too strong” for the Philharmonic. Robinson was not to be one of the two players who were finalists.

That should have been the end of it, but Robinson writes, “I knew that winning a once-in-a lifetime position like principal oboe of the New York Philharmonic was like winning the lottery.”

At 3 a.m. the next morning, using all his liberal arts writing and persuasive talents, he wrote Chambers explaining why his tone might have seemed too strong and, “You will not make a mistake by choosing Eric or Joe, but you might by excluding me if tone is really the issue.”

When Chambers read the letter to Mehta, they agreed that it could not have been “more persuasive or fortuitous.” Chambers reported that Mehta said, “If you believe in yourself that much, he will hear you again.”

Robinson’s final audition was successful. His “winning lottery ticket,” he writes, “had Davidson College written all over it.”

From 1978 until his retirement in 2005, he served as principle oboe for the New York Philharmonic. Living in Chapel Hill, he can still bring an audience to tears when he plays the beloved solo “Gabriel’s Oboe.” PS

D.G. Martin hosts North Carolina Bookwatch Sunday at 3:30 p.m. and Tuesday at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV. The program also airs on the North Carolina Channel Tuesday at 8:00 p.m. and other times. To view prior programs: http://video.unctv.org/show/nc-bookwatch/episodes/