Golfing, shooting or selling Sandhills real estate, Glenna Collett Vare was a star

By Bill Case • Photographs from the Tufts Archives

From her vantage point on the veranda, the lithe 14-year-old girl watched with interest as her father prepared to hit his drive from the first tee. In his younger days, George Collett won international bicycle racing championships but he could steer his way around a golf course, too. The memory of that shot in the summer of 1917, overlooking what Glenna Collett described as the “magic carpet” of the Metacomet Country Club in Providence, Rhode Island, became permanently imprinted in her mind. “I watched Dad send a long, raking tee shot through the air. It dropped far down the fairway, ” she recalled in Ladies in the Rough, a book she would author a mere 11 years later.

The ball’s soaring flight so captivated the teenager that she rushed to her father’s side with the enthusiasm of a child half her age flying down the staircase on Christmas morning. Despite never having swung a club, she saw no reason why she couldn’t smash a golf ball just like her dad and begged him to let her try. Collett’s self-confidence was grounded in her own athletic prowess. An accomplished swimmer, diver and tennis player, she could hold her own playing baseball with the neighborhood boys, too. Dad agreed to let her give it a go.

Brandishing her father’s hickory-shafted driver, Collett swung away. “With beginner’s luck my first shot off the tee went straight down the fairway,” she recalled. “The length and accuracy of my initial drive stirred the enthusiasm of my father and several spectators.” Elated and intrigued, George encouraged his daughter to play along. It became obvious that her first drive was no fluke. She struck one flush shot after another. It would be her golfing epiphany, writing later that her “head was bursting with the soaring dreams that only the very young and ambitious live and know. As I came off the course after the first game, my destiny was settled. I would become a golfer.”

Collett quickly learned that the naturalness of her swing did not automatically translate into stellar golf. On her next visit to the course, her shots boomeranged in all directions, and a floundering Glenna carded a horrifying and humbling 150. Though she drove it farther than other women at the club, Glenna’s subsequent rounds resulted in scores mostly north of 100. She confessed to being “terribly depressed at my slow progress.”

To lift his daughter out of her funk, George Collett retained two-time United States Open champion Alex Smith, who tutored his daughter twice a week for three years. As proficient a teacher as he was a player, the Scottish-born Smith’s whimsical instruction galvanized the young girl’s game. “Alex gave me a happy philosophy as well as an improved way of handling the putter and mashie,” she wrote. “He strengthened my driving to such an extent that . . . standing five feet six inches and weighing hundred and twenty-eight pounds, I drove a ball off a tee a measured distance 307 yards . . . the longest drive ever made by a woman golfer.”

By the age of 16 Collett acquitted herself with a measure of distinction (but no victories) in Eastern tournaments during the summer of 1919. Fearful that enduring the winter months in snowy Providence would stall her improvement, George and his wife, Adah, pulled their child out of school at Christmas break. While her father stayed behind to manage his insurance business, Glenna and her mother headed south to golf-mad Pinehurst, where they spent the first quarter of 1920 at the Carolina Hotel. While Glenna acknowledged that her chance of passing French back in Providence “went a glimmering,” playing in events like the North and South Amateur proved beneficial to her game. Extended annual visits to the Sandhills would become a happy staple of her life for the next 15 years.

By the time Collett arrived in Pinehurst for the 1922 winter season, she was recognized as an emerging force in amateur golf, the highest level of the women’s game at the time. In March, she captured her first major tournament on course No. 2 in the Women’s North and South, defeating an outgunned Edith Cummings in the final match 4 and 2. The Pinehurst Outlook observed that Miss Collett, as the players of the day were described, was “sure to win many important championships and to be one of the prominent figures in the game for years to come.” Later that season, she won the U.S. Women’s Amateur at the Greenbrier, consistently outdriving her opponents by 50 yards. The new champion revealed something of a superstitious streak. Having consumed lamb chops, stringed beans and cream potatoes the evening before a practice round in which she carded an excellent 75, Collett confessed to “eating the same thing every night as long as the tournament lasted.” She also “wore the same skirt, sweater, and hat.”

Her victory at the Greenbrier was a breathtaking achievement. No other golfer, before or since, ever won a major championship within five years after taking up the game. Public interest in all things Glenna rose to a fever pitch. The fact that the 19-year-old had become a stylish and attractive woman accentuated that attention. Collett acknowledged in Ladies in the Rough that the demands of new-found celebrity presented a wearing Catch 22: “Sooner or later the champion begins to realize that she is supposed to do this and that, either from a desire to be agreeable or an honest wish to live up to the sweet things said about her in sports columns. Most difficult of all is trying to be a ‘good sport.’ As such you are compelled to do many things you don’t give two hoots about, to go to parties when you just long to be in bed, to be nice to people, who ask all sorts of favors . . . but the champion, unless she has the skill of a diplomat, has no way of expressing her gratitude and at the same time refusing.”

Collett relinquished her U.S. Amateur crown in 1923 but successfully defended the North and South title. She also earned trophies at two Florida tournaments and the Canadian Women’s Amateur. Those successes would be dwarfed by Glenna’s monster 1924 campaign. Dubbed the “female Bobby Jones,” she won 11 of the 12 tournaments she entered (including her third straight North and South championship), prevailing in 59 of 60 matches. Her only defeat came at the hands of Mary K. Browne in the semifinal of the U.S. Amateur when, putting from 20-feet on the 19th hole, Browne unintentionally caromed her ball off Collett’s into the hole to close out the match.

Regaining her U.S. Amateur title in 1925 at St. Louis Country Club, Collett capped the championship with a 9 and 8 blowout of the veteran Alexa Stirling. Having retaken America’s most important title, she sailed across the Atlantic in an attempt to win a historic double at the British Women’s Amateur. For once, she found herself overmatched, facing England’s Joyce Wethered in the third round at rugged Troon. When the match ended after 15 holes, the brilliant Wethered stood five under par, leaving her American opponent in the dust. It was the first of several near misses for Collett in that championship. “More than once I have visualized myself, gray-haired and stooped, wearily trudging over the windswept fairways of an English course seeking that elusive title,” she wrote.

The disappointment did little to detract from Collett’s victory parade in America. With each triumph, her star glowed brighter. The legendary Donald Ross considered Glenna’s presence at the resort to be “good advertising,” and her amiability attracted a growing coterie of Pinehurst friends and admirers. Since the queen of American golf had chosen Pinehurst for winter lodgings, a glittering array of eager challengers followed suit. Virginia Van Wie, Helen Hicks and Maureen Orcutt, all championship-caliber players, visited frequently. Collett welcomed her fellow competitors, squaring off against them in tournaments, exhibitions and friendly one-on-one matches.

The 1920s were a golden time in Pinehurst. In addition to the female stars, legends like Walter Hagen, Tommy Armour, Bobby Jones and Jock Hutchison habitually visited, displaying their expertise on the resort’s courses. Golf aficionados flocked to the area in droves, not just to play but also to mingle with their heroes — both male and female.

In 1920, Leonard Tufts sought to capitalize on the good times by launching a real estate venture on 5,000 acres adjacent to the pathway of the old Yadkin Trail (now Midland Road) between Southern Pines and Pinehurst, forming Knollwood, Inc., whose stockholders included himself, Ross, New York steamship lines magnate James Barber, H.A. Page, Pinehurst, Inc., and Waldorf-Astoria, Inc. The first phase of that development was completed in 1924 with the opening of the Mid Pines Country Club, and its 118 room hotel, imposingly situated just behind the 18th green of the Ross-designed course.

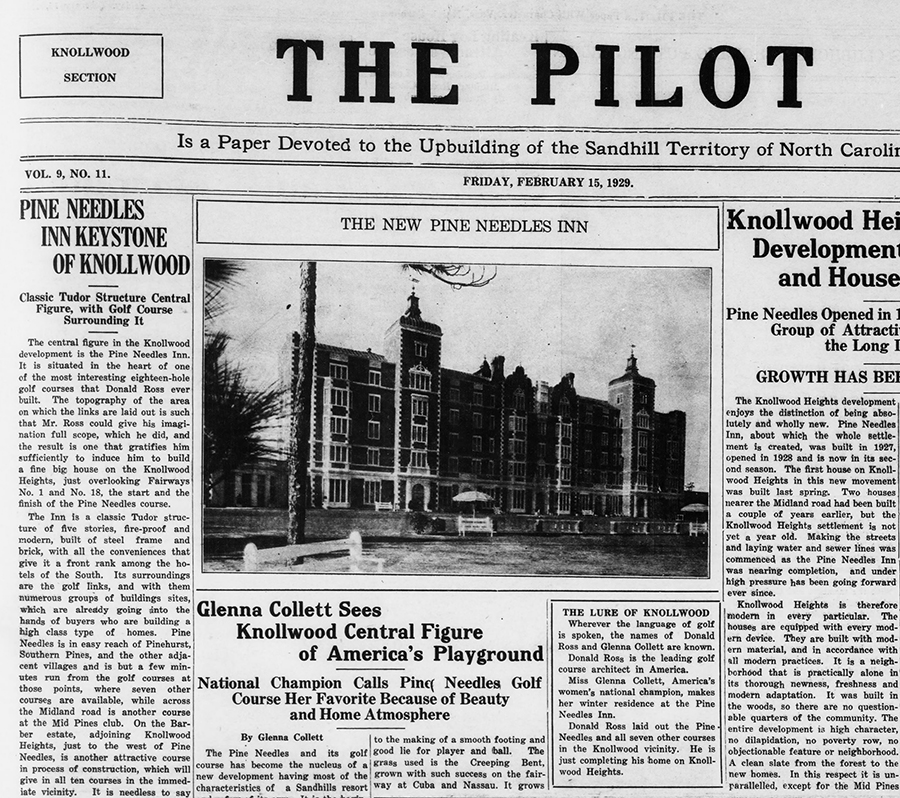

In January 1927, Leonard and the other shareholders embarked on a more ambitious phase of the development involving the subdivision and selling of hundreds of residential lots, many adjacent to the new Ross-designed Pine Needles golf course. A key aspect of the plan was the erection of the Pine Needles Inn (now Pine Knoll at St. Joseph of the Pines), a towering Jacobean structure that wowed all who saw it. The normally conservative Tufts reckoned that the booming economy and the imminent widening of Midland Road would result in brisk sales of lots and concluded the risk of borrowing money to finance the project would be minimal. Leonard’s own company, Pinehurst, Inc., was among the entities loaning substantial sums to the venture.

Construction of the golf course and inn proceeded apace. Casting about for a big name who would entice guests to the Pine Needles Inn after its scheduled opening of January 28, 1928, the Knollwood brass thought of Collett, adored by just about everyone. In The Story of American Golf, Herbert Warren Wind likened Collett to his favorite actress, Ingrid Bergman, since both women gave “majestic performance[s] when at work” but “generally scorned the queenly manner.” The admiring Wind praised Collett’s “fine sense of humor at her own expense; she added verve to a party with her high-spirited playfulness; and she was that very rare thing, a good winner.”

In exchange for room, board, free golf and some unknown stipend for herself and her mother, Collett accepted Knollwood’s proposal that she assist in promoting Pine Needles. She and Adah would relocate from the Carolina Hotel to the Pine Needles Inn on its opening day. The Pilot’s Bion Butler heralded Glenna’s arrival in his December 9, 1927 editorial: “She will be a feature of Sandhills outdoor life and probably her admirers will see that she is a central figure in much social contact in the house [Pine Needles Inn].”

Another marketing idea occurred to Leonard Tufts shortly after the New Year. Wouldn’t it be great for Pine Needles to host a women’s tournament coinciding with the opening of the hotel with Collett as the main attraction? Ross had doubts whether the event could be staged with only 30 days’ notice. “I don’t know how much Miss Collett’s say-so would help,” the famed course designer wrote Leonard, “but it might because of the fact she knows them personally.” But Collett’s say-so did have clout, and she successfully recruited a strong field of 54 players for the Mid-South Open, contested a few days after the inn opened for business.

While promotion of Pine Needles and its facilities was important, the Knollwood investors were primarily concerned with generating cash flow from the sales of lots. The Pilot collaborated with Knollwood, running articles above the fold unabashedly highlighting each lot sale, and generally serving as the project’s enthusiastic booster. In one editorial, Butler opined that Knollwood’s success was of paramount importance to “the whole united interest of the whole Sandhills community, for we all advance or stand still or go back together.”

To augment The Pilot’s unwavering support, Knollwood manager J. Talbot Johnson and real estate agent Samuel B. Richardson (both of whom were Knollwood shareholders) embarked on a hard-sell advertising campaign to market the lots. After Ross bought two lots, an ad informed potential buyers that, “Donald Ross is the best authority in this country on values of real estate in the golf belts . . . He puts his money on Knollwood Heights.” Another gambit stressed the fine neighbors one would have by purchasing in Knollwood — most of them wealthy. “Mr. Sylvester,” says one Richardson ad, “is one of the big men in American finance as NCB has resources of around a billion dollars and heads everything else in the continent.” Richardson also stressed that “lots were going quickly” in the “buying whirlwind” and hesitant buyers should pull the trigger while there was still time. “Look at the maps in Richardson’s office,” (located at the Arcade Building — currently Morgan Miller and Framers Cottage — in Southern Pines), “and see how these lots are melting away.”

Well, lots were not “melting away” quite as fast as the Knollwood men intimated, but assistance in marketing them would come early in 1928 from an unexpected source — Glenna Collett. It’s not clear what led to her role in arranging and closing the sale of a lot to Wisconsin real estate operator Robert Whittaker in early February, 1928, but whatever it was, Sam Richardson began touting her as a saleswoman extraordinaire. Richardson’s ad in the February 12 Pilot suggested that potential buyers visit Miss Collett at Pine Needles and “get her to drift about Knollwood Heights with you and talk golf and home sites. She will be glad to as she is an enthusiast about Pine Needles and she says she will be glad to sell more Knollwood Heights lots.”

The Pinehurst Outlook also talked up Collett’s sales acumen, saying she was “as hard boiled in procuring a down payment as she is driving off the tee.” For her part, Collett insisted to the Outlook’s columnist “there is no reason why a woman should not be as good a salesman as a man.” She added that participation in sports “especially golf, should be a great help to a woman in business.” Glenna was not the only great amateur golfer selling golf course real estate. The star with whom she was often compared, Bobby Jones, was similarly employed in Sarasota, Florida.

The Whittaker deal jump-started an impressive sales streak by Collett that continued until her return North in April 1928. Richardson’s ads in The Pilot reported them all. The February 17 edition proclaimed “Glenna Collett in action again” after she engineered the sale of lot 456 to Connecticut state Senator Wallace Pierson. On March 9, The Pilot disclosed that Collett had sold three lots to Messrs. Sylvester and Brasleton. On April 13, her biggest real estate score yet made the headlines of the paper when she convinced Michael Meehan to purchase an entire block of seven lots, then talked him into buying five more for his daughter Betty Elizabeth. On a roll, she arranged George Van Kueren’s purchase of three more lots.

Her sales pitch was low-key. Richardson advertised that “Miss Collett has none of the hurrah, boys, style, but she simply interests her friends in discovering what they are anxious to find — the best spot on earth for a winter vacation, and she is a big influence in gathering the golf army together in the Sandhills.”

Collett won her third U.S. Amateur title at The Homestead in the summer of 1928, annihilating her friend Van Wie in the 36-hole final 13 and 12. Talbot Johnson recognized that her status as current national champion rendered her even more valuable to Knollwood. Notwithstanding Johnson’s concern that “selling lots is so secondary to [Collett’s] golf that even the best land prospect would have to wait,” he urged Richard Tufts (Leonard’s son) to arrange for her return for the 1928-29 winter season. “I imagine Glenna is going to be more popular than ever this year on account of having again won the championship,” Johnson wrote. “I am convinced that her name is quite an asset to both Pinehurst and Knollwood and she is a good drawing card for both.”

According to Johnson, Collett’s mother was keenly aware of her daughter’s marketability. Skillfully playing the role of unofficial agent, Adah never passed up an opportunity to remind Talbot that she and Glenna were constantly receiving “propositions from hotels offering not only to give them free board, but to pay railroad transportation.”

Collett and her mother eventually came to terms with Knollwood for a second year. They would bivouac at the Carolina in December, and then stay at the Pine Needles Inn after that house opened mid-January. Both The Pilot and Knollwood stepped up the marketing campaign in anticipation of their arrival. “With Glenna Collett and Mrs. Collett advocating the delights of Knollwood Heights as a place for a home in the North Carolina golf and vacation belt,” trumpeted one editorial, “the additions to Knollwood’s group this winter will be large.” Glenna herself penned a lengthy article on February 29, 1929, extolling the virtues of the Pine Needles course and Knollwood’s atmosphere. “I have come to prefer the new Pine Needles course to any of the others in the Sandhills,” she enthused, “because of its beauty and the associations that make it seem like home to me.”

Despite the hullabaloo, real estate sales activity slowed to a trickle that winter. Few were buying. Even Collett’s star power was insufficient to reverse the trend, and events in her life contributed to her sales slump. Still mourning her father’s untimely death in 1928, the presence of a handsome blueblood Philadelphian vacationing in Pinehurst provided a further distraction. The name of Edwin H. Vare, Jr. began popping up in The Pilot, linked with Glenna’s. The March 1st Pilot reported that Collett had fired a magnificent 73 at Pine Needles and Vare, her playing partner, carded 85. Vare attended a dinner dance in Glenna’s honor at Lovejoy’s log cabin restaurant in Southern Pines (once located near the present Methodist Church). A romance blossomed. Though not selling many lots, Collett kept busy promoting and playing in the second Mid-South Open at Pine Needles. It was the first tournament in women’s golf where amateurs competed against female professionals. The Chamber of Commerce raised a whopping $50 in prize money.

By the start of the Sandhills’ 1929-30 winter golf season, the shock of the stock market collapse and the looming Great Depression brought prosperity to a screeching halt. Even the wealthy shied away from building “winter homes.” Knollwood could not afford to keep Collett on the payroll despite her repeat victory in the U.S. Amateur championship. However, that did not stop her from continuing her brilliant play while in the Sandhills. She won her record sixth North and South title in March, and participated in an exhibition at Southern Pines Country Club that drew 2,000 spectators. In the summer of 1930, Collett carried home her fifth U.S. Amateur trophy (and third in succession), defeating old rival Van Wie at Los Angeles Country Club. That year, she organized a team competition between the best amateur female players of America and Great Britain that presaged the first Curtis Cup played two years later. Her sole golf disappointment was another defeat by her old nemesis Wethered in the British Amateur final at St. Andrews. Despite the result, Collett viewed the nip-and-tuck match as the most exciting of her career.

Vare and Collett married in June 1931, and she joined him in Philadelphia. The newlyweds would weather the Depression, but the fortunes of Knollwood and Pine Needles plummeted. The inn would shut its doors in 1931 and remain closed until new ownership reopened it in 1935. Creditors forced the liquidation of Knollwood’s assets. Fortunately, the Tufts’ lenders allowed the family members to retain their holdings in Pinehurst.

Glenna Vare dropped out of competitive golf in 1933 after giving birth to son Ned, then daughter Glennie, but she would author a memorable comeback in the 1935 national amateur at Interlachen Country Club in Minneapolis. Smashing her drives far past her finals opponent, the 32-year-old sentimental favorite bested 17-year-old Patty Berg 3 and 2 to record her never equaled sixth national amateur championship. ”I wanted to put ‘Vare’ on that trophy,” the always-competitive Glenna confided to a friend.

After her resounding triumph, Vare gradually faded away from golf on the national stage, though she continued to play in area events on and near her home course, the Philadelphia Country Club. She discovered new areas of sport to her liking. She trained sporting dogs for field competitions and found her excellent hand-eye coordination translated nicely to rifle shooting. The Vares would visit Pinehurst intermittently over the succeeding years, but sometimes without touching a club. Recounting her achievements during a visit to the Sandhills in 1947, The Pilot marveled that “the versatile Mrs. Vare was the top hand among the women at the skeet range. She has won many titles in her Philadelphia district for her skeet shooting, and she fires from scratch against men and women. She is a crack shot in the field also, and trains her gun dogs for field trials. She rides, swims, dances, and plays bridge just a little better than most anybody else.” While vacationing in the Sandhills in 1956, Glenna pulled off an unusual triple, claiming the medal in a pairs golf tournament, shooting 49 out of 50 targets in skeet, and winning a field trial with her dogs.

As the decades passed, accolades came Mrs. Vare’s way. She was inducted as a member of the inaugural class of the Women’s Golf Hall of Fame in 1950. Though never turning professional, the LPGA honored her by establishing the Vare Trophy, awarded annually since 1953 to the pro with the lowest scoring average. She received the United States Golf Association’s Bob Jones award for sportsmanship in 1965. She would be elected to Pinehurst’s World Golf Hall of Fame in 1975.

As she aged, Glenna devoted much of her time to her family. She reveled in son Ned’s accomplishments on Yale’s golf team, and doted on her grandchildren. She enjoyed summers back in her native Rhode Island, golfing at Narragansett’s Point Judith Country Club with family and friends. According to golf writer Bill Fields, who devoted a chapter to her in his book, Arnie, Seve, and a Fleck of Golf History, she competed in the club’s Point Judith Invitational for more than 60 years, invariably hosting a lobster dinner for her visiting friends.

In 1986 PineStraw editor and best-selling author Jim Dodson interviewed Vare in Narragansett for a story in Yankee Magazine. Then 83, widowed, and still proudly sporting a 15 handicap, Vare bossed him about, ordering Dodson to make himself useful chopping vegetables for soup. At first she stiff-armed any discussion of her golfing career, believing she’d been largely forgotten. Dodson’s Yankee story was subsequently republished in the USGA’s Golf Journal, helping to bring Vare’s exploits to the attention of a generation of golfers unaware of her accomplishments. She passed away three years later in Gulf Stream, Florida. Her daughter Glennie Kalen still lives in her mother’s old haunt of Narragansett and remembers her mom as “reserved, funny, and lucky.”

The latter must have been transferable. While captaining the U.S. side in the Curtis Cup, Vare found a four-leaf clover that she immediately picked and handed to Peggy Kirk, who was struggling mightily in her singles match. The woman who would eventually own Pine Needles with her husband, Warren Bell, rallied to win. If luck be a lady Glenna Collett Vare was her name. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.

World Golf Hall of Fame member JoAnne Carner, a five-time winner of the Ladies Professional Golf Association’s Vare Trophy, shot her age last year in the inaugural U.S. Women’s Senior Open Championship won by fellow Hall of Famer Laura Davies at the Chicago Golf Club. The 2nd U.S. Women’s Senior Open Championship will be conducted at Pine Needles Lodge and Golf Club May 16-19. Entries open Feb. 20. Championship tickets and packages can be purchased at USGA.org.