An unforgettable game drive

Story & Photographs by John Earp

Wake-up comes at 6 a.m. with the room attendant lightly knocking at the tent entrance and whispering just loud enough, “Good morning.”

Groggily we dress and assemble the camera gear, binoculars and warm-weather clothes we’ll need for the all-day drive. At the Olonana Lodge we take a moment to watch the sunrise, then move to the Land Cruiser following Joseph, our guide, who has treated us to the scenes of the Masai Mara — the giraffes, zebras, water buffalo, hippos and rhinos — for the previous two days.

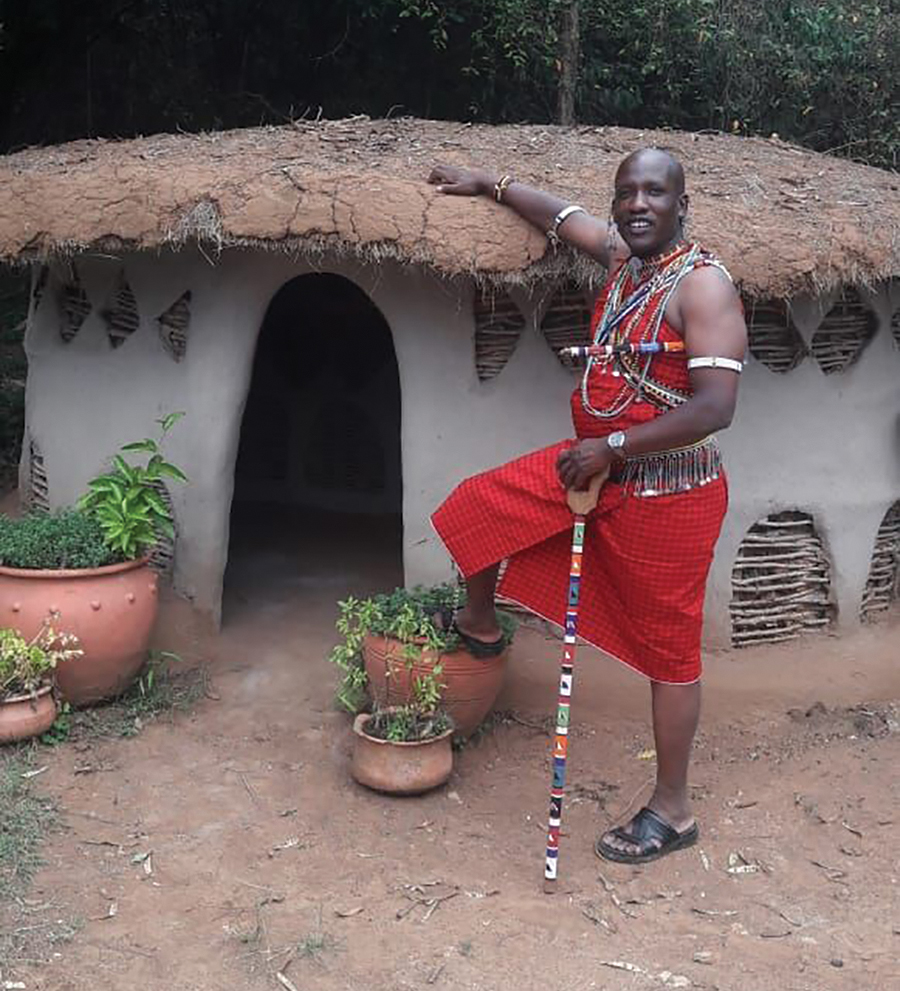

Joseph Koyie is a prince among guides and a Maasai warrior. Like all of the Maasai we encounter, Joseph is confident, but not arrogant, and treats us as guests in his home, being neither obsequious nor condescending. He is the recipient of the 2015 Eco-Warrior Guide award, the 2015 Born Free Foundation Guide of the Year and an occasional instructor at the school now required for all Masai Mara guides. He established Under the Acacia Tree Foundation, a nonprofit organization to provide schools and water systems for his community, and has lectured internationally on the Masai Mara and its people, the Maasai tribe.

The Maasai are warriors who live a simple life true to their ancestors. There is no electricity. They share a common compound circled by upright tree branches often reinforced by thatch to keep predatory animals out. Inside the compound is a secondary circle made of the same tree branches as a pen for the Maasai cattle, sheep and goats. Cattle are the Maasai currency. They use it for trade and most importantly as the dowry from the groom to the bride’s family.

As we head out the Olonana Lodge gate we turn right, heading north to begin an elongated circle through the greater Masai Mara, eventually winding our way south toward the Tanzanian border, then north again. The sky is exceptionally clear, bright blue and without a cloud, endless and unbroken. After 3 kilometers we turn right and cross the Mara River, a modest waterway about 10 meters across that, in the rainy season, will be a raging current, double in width and impassable.

We head along a rocky, uneven, bone-jarring road and pass a small commercial area reminiscent of an Old West frontier town. It looks rough and no doubt is. There are general stores, specialty outlets, churches and bars but not many inhabitants. Soon we turn south, back into the Masai Mara Reserve. The landscape is savannah with tall grass occasionally broken by the umbrella-like African acacia tree. Mara means “spotted” and Masai “earth,” the image you get as the sun casts shadows of the lone trees. It’s still early and the most likely opportunity to spot cats. Joseph is methodical about hunting out sites where we might find a lion pride as we move across the grassy plain. There is no pattern to spotting wildlife. It simply happens.

Along the Mara River near the Kichwa airstrip — little more than a dirt road carved into the earth where we first landed — we spot two lionesses with five cubs in a scrum constantly lagging behind their mothers, who haphazardly stalk a small herd of impala. It’s a harem, a single buck with a number of females. The buck stands forward of the females, grunting. All face the lions with the intensity of the shared danger. Distance is the best defense. As the lions come close the impala retreat, then again make a stand. The pattern is repeated until the lions tire of the ritual and move on.

Joseph navigates east to the Topi Plains, a grassy land of rolling hills known for its large herd of topi, a close relative to wildebeest. They have generally reddish brown skins except for the black patch that covers the front of the face and sides of their legs. We see thousands, speckling the hills far into the distance with several lone topis standing atop mounds in a stoic pose, like Centurions.

Farther east is the area known as the Double Crossing for the two small streams that converge across the road. Joseph fords two deep river beds in a matter of minutes, spots something and goes off-road. He turns toward a dry river with a grassy island and a lone tree. As we get close, a lion raises up. It’s clear there is more than one, and we stop at a safe distance to count. Ten, all lionesses and cubs, lying on this small patch separating the two riverbanks. Most are sleeping. Lions are lazy. A large monitor lizard insinuates itself among the lions, who pay it no mind. After several minutes of still life with lions, we move on.

Soon we see three jeeps stopped beyond a patch of bush. Three cheetahs are tearing into a freshly killed Grant’s gazelle. Observing from a distance, dozens of buzzards are joined by dozens more who parachute in to join the dance of anticipation, sitting on the sidelines waiting for the cheetahs to reach their fill and give up their prize. As the cheetahs feast, a single buzzard hops closer to test the cheetahs’ resolve, but they quickly stare him down. Finally sated, two cheetahs move back to the bush to lie in the shade. A single cat remains, and the buzzards feel their opportunity is near. More and more, they inch closer to the gazelle, and the remaining cheetah becomes increasingly assertive, defending its kill until it, too, tires of the game, exhausted and full. As the cheetah begins to walk away, the buzzards descend on the dead animal. The cheetah feints toward them a couple of times but eventually cedes them their meal. The buzzards mass over the carcass. Like flying piranhas they tear apart the animal’s remains. In a matter of 10 minutes there is little left but bones. The hyenas will soon come and devour the remaining meat, then the bones themselves.

With the Land Cruiser bucking and shifting on the uneven terrain as we drive, we see an almost endless rolling plain swarming with small brown dots. Joseph explains that the massive herds of wildebeest that migrated to Tanzania’s Serengeti Plain are making an unusual reverse migration. A lack of rain in the Serengeti, in combination with an extended rainy season in the Masai Mara, has inspired the wildebeest to return to the greener grasses on the Kenyan side. Hundreds of thousands of wildebeests spread out across the rolling savannah. As we drive through, they move aside like Moses parting the Red Sea.

Joseph stops near an acacia tree, where we break for lunch. He brings out the hardware — tables, chairs, plates, utensils. Eating in the bush is a bit surreal, as if you’ve gone back in time. The wildebeest file around us as we drink Kenya’s most popular beer, fittingly named Tusker. In the distance we can see the long lines of wildebeest marching in single file as they move up from the Serengeti. We speak about the day, finish lunch, load the Land Cruiser and climb back in, taking a dirt road southwest toward the Tanzanian border.

After a short drive we come on a tall mound called Lookout Hill offering a grand vista. We look back and see the fields of wildebeest, then head south, moving closer to the border, where we see a bat-eared fox. We stop and Joseph pulls out his binoculars. He stares intently through the glasses and then throws the truck into gear. Off-road again we jostle along and then stop. To our left, 10 feet away, is a serval with a beautiful spotted fur coat, a rare sighting in the daylight. This cat would normally rush into hiding, but not this time. It walks alongside the Land Cruiser at a paced gait, seemingly undisturbed. After a flurry of pictures we move on.

Passing over the Mara River again, we arrive at the Tanzanian border. Joseph moves on to an improved road and we pick up the pace, then come to an abrupt stop. Behind us walking calmly aside the road is a large male lion. We watch as he passes our vehicle, indifferent to our presence. Slowly, methodically, he moves on, keenly aware of his place in the hierarchy of the Masai Mara.

Joseph keeps a quick pace, aware we must be out of the reserve by 6:30 p.m. After a long drive north we move off the smooth surface to an unimproved road, turn back to the Mara River, then continue parallel to it. We are getting close to the Olonana gate, the exit from the reserve, when someone points out several elephants. Joseph turns toward them. We come to a stop. It’s a huge matriarch and a few followers. The matriarch looks us over and moves forward, only a few yards from our vehicle. Then from a deep, wooded area come more elephants. Then more and then more. Parked along the side of the road, the great, gray mass begins coming in our direction. They walk toward us one by one, slowly. As they come close they veer off in front of the truck. More elephants come out of the bush and continue their walk past the truck. One, two, three . . . 82, in all sizes and ages. No one says a word. Pure silence except for the jostling sound of the elephants stepping through the high grass as they sway by.

In the wake of the elephants, we move toward the gate with a sense of urgency. Joseph responds to a call on the radio. He turns toward the Mara River and drives to a handful of safari vehicles. We pull up beside them and in front of us is a leopard. Many a dedicated wildlife enthusiast will go years without seeing one. Nocturnal by nature, here, in the late afternoon, is a mature male. Beautifully spotted. Lying upright. Face forward. Keen of its surroundings, indifferent to the vehicles, eyes focused ahead on the open savannah. It stands up and begins to pace forward. Toned and muscular, it represents everything majestic the creatures of the Masai Mara epitomize: confidence, self-awareness, elegance, focus and the indomitable need to survive. As more vehicles pull up, we pull away.

Joseph heads to the Olonana gate and we make it with a few minutes to spare. Dusk is settling around us. Darkness is not far away. The road back to the lodge is rough with large rocks and an uneven surface. No one complains. We’re all exhausted. The drive has lasted 10 hours and covered almost 200 kilometers. We turn into the Olonana gate and stop in front of the main lodge. A handful of attendants pass out hot towels scented in eucalyptus. The smell clears the sinuses and draws out the day’s dust. We gather our gear, thank Joseph, and walk back to our tents to await the next morning’s knock. PS

During his career with the Ford Motor Company, John Earp visited every major country in Africa and, with his wife Catherine, had the good fortune to live in South Africa.

Reflections of Africa

The Arts Council of Moore County, in collaboration with the English-Speaking Union, Ruth Pauley Lecture Series, Sunrise Theater and Penick Village, offers a weeklong and multi-venue program exploring the unique diversity of African culture and wildlife through a series of lectures, films and art exhibitions.

Sunday, Jan. 27 — Out of Africa, 2:30 p.m. Sunrise Theater, 250 N.W. Broad St., Southern Pines, free and open to the public.

Tuesday, Jan. 29 — Joseph Koyie: “Maasai Culture,” 9:00 a.m., Penick Village, 500 E. Rhode Island Ave., free and open to the public.

Wednesday, Jan. 30 — The Forgotten Kingdom, 7:30 p.m., Sunrise Theater, 250 N.W. Broad St., Southern Pines, free and open to the public.

Thursday, Jan. 31 — Ruth Pauley Lecture Series, Joseph Koyie on “Masai Mara Wildlife,” “Maasai Culture and Becoming a Maasai Adult,” 4:00 p.m., Sunrise Theater, 250 N.W. Broad St., Southern Pines, free and open to the public.

Friday, Feb. 1 — Reflections of Africa Art Exhibition, Garth Swift, Jessie Mackay and Patricia Thomas, 6:00 p.m., Campbell House Galleries, 482 E. Connecticut Ave., Southern Pines, free and open to the public.

For additional information, call (910) 692-2787 or visit MooreArt.org.

Joseph Koyie — Naturalist

Joseph Ole Koyie was born in the Loita Hills, at the Eastern corridors of the Masai Mara Reserve in Kenya. He has a professional diploma in wildlife management from Ron and John Feldman College. He joined Sanctuary Olonana in 2010 as the head naturalist. Joseph is passionate about his Maasai culture and the Masai Mara eco-system. His knowledge and reputation as a guide and environmentalist has earned him prestigious recognitions, including of Eco-Warrior Guide of the Year by Eco-Tourism Kenya and The Best Guide in the Masai Mara by the Born Free Foundation. He established Under the Acacia Tree Foundation, a non profit, that helps build schools and water resources in rural villages.

Garth Swift — Artist

Growing up on a farm in Zimbabwe through the ’60s and ’70s, Swift was exposed to wildlife in its natural habitat from an early age. He attended the Natal Technikon in Durban, South Africa, where he studied fine art, majoring in graphic art and printmaking and began experimenting in watercolor, his first love. “I love the feel of it, the way the water washes over the paper, leaving a faint residue of color, and then dries and fixes itself in an unplanned and accidental way,” he says. In response to collectors in the U.S. market, Garth began using acrylics on canvas for some of his larger works. “Visitors’ memories of the African bush, are of sweeping panoramas and big skies; that’s what I try to convey,” says Swift.

Jessie Stuart Mackay — Artist

Mackay’s work has been exhibited nationally in galleries across the country. Her paintings were in Architectural Digest on the walls of Mary Matalin and James Carville’s home in Alexandria, Virginia, and have been featured on “The Little Green Notebook — Adventures in Design” website by Jenny Komenda. “Color is what inspires me,” says Mackay. “When I look at a subject, the feeling I have is what determines the colors I use, not just what I see before me.” A resident of Pinehurst, Jessie received her degree from Oglethorpe University in psychology and is a self-taught artist. She’s involved in her non-profit, KARIMU, which focuses on Women’s Empowerment in Tanzania.

Patricia Fay Thomas — Artist

A Moore County native, art has been an integral part of Thomas’ life since childhood, when she received private instruction under N.C. artist Anita Jones Stanton, and later attended the Governor’s School. She received a bachelor of arts from UNC-Chapel Hill, where she studied a variety of mediums, with a concentration in painting. Just before graduation, a chance encounter with a U.S. Peace Corps recruiter resulted in her move to Burkina Faso, West Africa, where she lived and worked for five years. Afterward she settled in Quebec City, Canada, completing a master’s degree in sociology from Université Laval. She has worked for over 25 years in international development, both as a private consultant and at United Nations headquarters in New York City. Patricia now divides her time between Quebec City and Chapel Hill. Her solo exhibit, titled “Mapping the Moment,” was presented by the Galerie de l’Articho in Quebec in June of 2018. Her work can also be seen at Caffé Driade, in Chapel Hill. PS