Sculptor Zenos Frudakis and golf’s most famous statue

By Jim Moriarty

Absent the massive grandstands, the thousands upon thousands of people and the sound of the carillon bells from The Village Chapel, it was a day not unlike the one when Payne Stewart won the U.S. Open Championship almost 20 years ago. It was cool for the time of year, with an occasional spritz of rain. Larger than life in the moment, Stewart remains so, cast in bronze, facing the opposite direction than he did that day in June, still punching forward and kicking back. A man — approximately the age Stewart would be had he lived — with a belly making a jailbreak from the top of his khaki shorts and his left knee pinched in a black brace, stands next to what is arguably the most iconic golf sculpture ever created, and tries to strike “the pose” without falling over and injuring himself as his partners capture the moment on their cellphones. It is an occurrence behind the 18th green more common than all the pine trees on No. 2.

On October 25, 1999, a group of Pinehurst Resort and Country Club executives were returning from a trip to Scotland, decompressing after the massive undertaking of staging Pinehurst’s first U.S. Open. The night before at the Turnberry Hotel, owned now by Donald Trump, in a conversation that rose to the what-if stage, they bandied about the idea of a Stewart tribute. The next day, “we were paged at the Newark airport because Payne’s airplane had just gone down,” says Pat Corso, at the time the resort’s CEO. “At that moment, in the airport at Newark, it was decided we were going to do a statue.”

The sculptor commissioned for the job was Zenos Frudakis. The piece was unveiled roughly two years and two weeks after Stewart and five other people perished when their private jet suffered a catastrophic decompression after taking off from Orlando, Florida, and flew porpoise-like halfway across the country until it ran out of fuel and crashed into the most remote acres of a farmer’s field outside Mina, South Dakota.

Stewart’s widow, Tracey, and their children, Chelsea and Aaron, came to the dedication. The night before they ate at the Pine Crest Inn, Stewart’s favorite haunt. Dick Coop, Stewart’s sports psychologist, was there. So was Mike Hicks, his caddie, and Dixie Fraley, the widow of Robert, one of Stewart’s agents, who also died in the crash. They told stories that made them laugh. They told stories that made them cry.

“The morning was kind of misty and cloudy. There was a fog bank,” Corso recalls. “The fife and drum corps from St. Andrews University started down on the 18th tee. You couldn’t see them but you could hear them. Almost at the same time that they came out of the mist, the sun shines through. It made your hair stand up on the back of your neck.”

Frudakis was there, too. “Tracey, she was still so shaken. You could see,” he says. “I was next to her but I didn’t want to bother her. I felt like I would be trespassing on her emotions. Her daughter was very quiet. There was a kind of remoteness they both seemed to have.” Earlier in the morning Frudakis’ wife, Rosalie, went into the pro shop and saw Aaron sitting on the floor inside a circular clothing rack, hiding. “He was obviously very sad, very depressed,” says Zenos. After the statue was unveiled, Aaron was asked to recreate the 15-foot putt Stewart holed to win the Open. It took him one try more than his father.

Frudakis didn’t go looking for golf, it came looking for him. In ’96, an art dealer in Atlanta helped secure his services creating a statue of Arnold Palmer, destined for Augusta’s Riverwalk, for the Georgia Golf Hall of Fame. Since then, in addition to Stewart and Palmer, his golf resume includes Jack Nicklaus, the Bob Jones sculpture for the eponymous award the USGA bestows, and another piece for East Lake Country Club, where Jones grew up.

The studio where Frudakis works is in a carriage house tucked behind a modest home behind a wrought iron fence in a modest Philadelphia suburb. The two-story house, where he lives alone, would be a fixer-upper if he was interested in that sort of thing. He’s not. Four cats, Mr. Gray, Zane Grey, Evie and Bing Clawsby, have the run of the place. Though divorced now, Rosalie manages the art business from her office off the kitchen. He works until one, two, three in the morning, then decompresses by walking on a treadmill or playing the guitar plugged into a speaker the size of a Crock-Pot in a tiny room off his upstairs bedroom until the work recedes sufficiently into the night and he can sleep. The guitar was a gift from his friend Don McLean. The “American Pie” one. “Sometimes I think I’ve lived my art instead of my life,” says Frudakis.

The studio is crammed with heads and torsos; modeling tools passed down from artist to artist; a 10,000-year-old skull; photos everywhere, some as work, some as memories; clay with a pedigree and a whiff of immortality; sculpting stands, armatures, books and rolls of duct tape. Details are paramount. When he was working on Stewart, the family loaned him some of Payne’s plus fours and a pair of his shoes. Tracey saw her husband as a younger man than the one who passed away at 42, and Stewart’s bronze face is forever 10 years more youthful than the man who made the putt. Frudakis uses an oil-based clay that is nearly immortal itself; it doesn’t dry. He has clay once molded by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. “I don’t use it very much because it’s too small an amount,” he says. “I had more of D.C. (Daniel Chester) French. I just mixed that in with all my clay. It wasn’t enough to do a big figure so I thought if I just put a little bit in each of mine, then I’ll know it’s in there.” He has clay from James Earle Fraser, creator of The End of the Trail.

There is no shelf, no corner of the studio, to look at that doesn’t look back at you. Benjamin Franklin. Ulysses S. Grant. Martin Luther King. Bernard Darwin. The boxer James J. Braddock — Cinderella Man. Clarence Darrow. Enrico Fermi. Philadelphia Phillies Mike Schmidt and Robin Roberts. Albert Einstein. Alexis de Tocqueville. And, of course, Stewart.

Here, by the stairs, are diplomas and citations — the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts; an honorary doctorate in Italy. Over by the door is a wall of photos. “I like to interview people, so I get to know them,” he says. “You try to find some common ground, a bridge, so you’re not two isolated islands.” There’s Nicklaus posing. “What do we have in common? The hard work. Nicklaus told me that he practiced until his hands bled when he was young. He asked me, ‘Do you golf?’ I said, ‘No. Do you sculpt?’” There’s Palmer sitting. “See how he’s depressed? Someone came over and whispered. He just had a friend die,” says Frudakis. “Later we’re having dinner and I noticed people want his attention. He let his dinner go cold and he went to talk to people. And that’s who he was, I think.”

Here are the photos from evenings at the Lotos Club on 66th Street in New York, a literary club founded in 1870. Frudakis did a bust of Mark Twain for them and has been a member for over 20 years. Carol Burnett. Tony Bennett. Dick Cavett. Ken Burns. Yoko Ono. Harry Connick Jr. Tom Wolfe. His friend McLean, of course. And Gen. David Petraeus. “Don and Petraeus talked because Don, when he was a young man, played at West Point and Petraeus said, ‘You don’t know this but I was in the audience and I remember you saying you were going to take all the money you made for the show and give it to Veterans Against the War. And I thought, that young man has a lot of courage.’”

The Lotos Club is a distant commute from Gary, Indiana, where Frudakis grew up. “My father came from Crete. He was born in the 1800s,” says Frudakis. A bust of his father, Vasilis (he was called Bill), is the first piece Frudakis sculpted. “He came over and worked in the mines. Wyoming or someplace. Lost his eye on the right side. That side of his mouth was damaged, too. Dynamite blew up in his face. The person next to him got killed,” he says. Bill left his first wife and family to marry a woman 30 years younger than himself, Zenos’ mother, Kassiani, who was born in Somerville, Massachusetts, but grew up in Greece. “My father was 60, probably, when I was born.”

The second Frudakis family settled in Gary, with a three-year stopover in Wheeling, West Virginia. Zenos’ father owned bars and restaurants in both places but gambling was his real vocation. “Which was not good for us,” says Frudakis. “Everything else came in second. My father always carried a pistol. It was a little Wild West. He was a little bit fractured, a little maybe bipolar, a little manic-depressive. Maybe a lot.” Frudakis says one winter night in Gary, his father chased him out of the house at gunpoint. Hours later his mother opened a window to let him crawl back in. He says when they lived in Wheeling, his father decided to win an argument with his mother by stopping their car on a bridge, taking young Zenos out of the back seat, and dangling him over the railing.

Frudakis graduated from Horace Mann High School in Gary. Other alums of the illustrious school include Tom Harmon, the football star, and Frank Borman, the astronaut. He ran track. “You want to work hard enough so you don’t finish the race and have something left,” Frudakis says. “I used to run in high school, if I hit a finish line and I had anything left, if I wasn’t really collapsed, I knew I could have done better. I was frustrated. You got to be empty when you get there.” He worked at U.S. Steel as a cinder snapper, among the dirtiest jobs in the mills, using a wide-nosed shovel to throw cinder and coke into a 3,000-degree furnace, then covering your face with the blade to shield it from the heat.

Frudakis did, however, have someone to look up to. His half-brother from his father’s first family, EvAngelos Frudakis, was a successful artist in New York. “I remember when I was like 10, my father would show me pictures of Angelo’s work. He was a star at his art school. He got the Prix de Rome. He’d go to Europe. My father would say, ‘Look, he’s got these awards. Look at the sculpture he did. What are you doing?’”

He was finding his own art. “I knew about my brother and I could draw. All through school I had kids behind me, teachers, looking at what I was doing, so I knew I had something that I did that was special and it made me feel important,” he says. “I studied every day when I was in second, third, fourth grade, in Wheeling and then in Gary. I would draw from art books. I was training myself. I was 21 before I went to art school, before I got any serious instruction.” First it was the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, then the University of Pennsylvania. His brother became his mentor. One of EvAngelo’s sculptures, The Signer, is on the corner of 5th and Chestnut in downtown Philadelphia. He let Zenos do the feather. “He probably redid it,” says Frudakis, laughing. EvAngelo, who also lives in Philadelphia, is in his 90s and still sculpting.

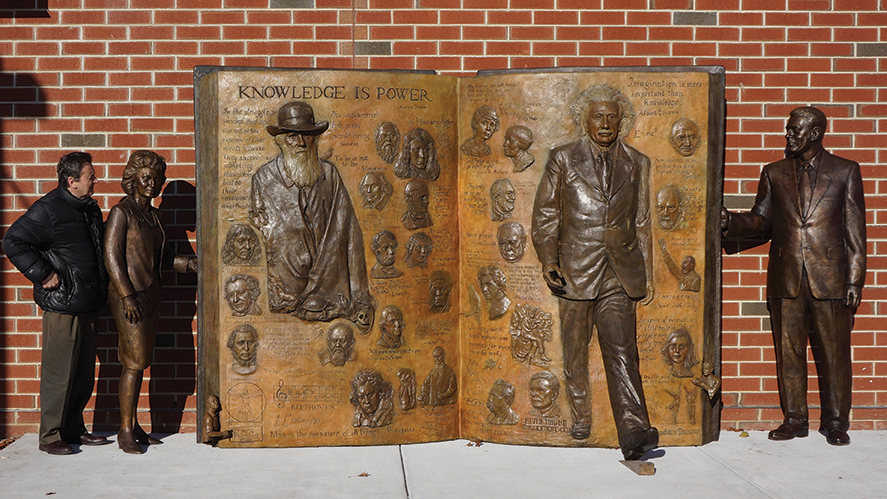

Frudakis’ first big commission, no pun intended, was an elephant for a mall. His body of work has grown larger than life-size to include public figures, sports figures, The Workers’ Memorial in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, The Honor Guard at the Air Force Academy, figure sculptures Flying at the Capital Center in Indianapolis and Dream to Fly, three figures in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. In North Carolina he’s memorialized the singer Nina Simone in her hometown of Tryon, welding a heart inside the chest of the sculpture to entomb her ashes. He did a bust of General William Pelham Yarborough that’s at the Airborne and Special Operations Museum in Fayetteville and a statue of Frederick Law Olmsted holding a stylized blueprint at the North Carolina Arboretum in Asheville. “It’s basically the design of where he’s standing,” says Frudakis. “I wanted to see him as a thinker, a creator. It’s unique to him.” Near the Stewart statue is Frudakis’ sculpture of Bob Dedman Sr. “I’ll never forget one day when my girls were like 4 and 2, we took them to Pinehurst,” says the resort’s owner, Bob Dedman Jr. “My littlest daughter went up and started knocking on my father’s statue thinking he might be inside.”

His golf works notwithstanding, Frudakis is probably best known for Freedom, his sculpture at 16th and Vine Streets in Philadelphia. The Rodin Museum, housing one of the many versions of August Rodin’s Gates of Hell, is nearby on Benjamin Franklin Parkway. “My brother studied with somebody who studied with Rodin. Rodin studied with people who knew Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. It goes back to the Renaissance, to the ancients. It keeps getting passed down,” he says.

In Freedom there are four figures in various stages of liberation from a 20-by-8-foot wall of bronze. As the figure struggles to break free, it becomes more developed. “I can’t just show a free figure. You don’t just get free. You have to have the opposite. To know dark, you have to know light. To know cold you have to know hot,” he says. The wall, like Rodin’s Gates, includes many smaller pieces within the larger sculpture. “In nature if you see a tree from a distance, it has a big design. But as you get closer, it’s got more things to see, right down to the veins in the leaves. We’re part of a larger whole. My favorite poem is T.S. Eliot’s The Four Quartets. He had a lot of personal references in there.”

The same is true of Freedom. His father’s bust is included, but it’s fractured, broken like the man. Frudakis’ sculpture tools are in the wall, as is his hand. Coins add up to his birthday. A pet cat, Kitia, that passed away is memorialized. And on and on. “As close up as you get or as far back as you get, there’s something to see. So, when people are walking by — as opposed to driving by and getting the big picture — if they get up close it’s going to take years for them to find all the stuff that’s in it. The world works that way. Everybody wants to be free of something.”

When Pinehurst’s executives commissioned Frudakis to do the Stewart statue — a minor engineering project given the figure is balancing on one leg, requiring internal steel support — they knew in the Newark airport what they wanted the pose to be. After all, what other choice was there? It’s their One Moment in Time. But nothing stands still for Frudakis, even in bronze. “People tend to see the moment before, the moment of and the moment after. They kind of put it together,” he says. “Rodin’s John the Baptist Walking, has the front part of the figure in one moment, the back part is in another moment, so there’s a little bit of flow. It’s not stiff. I tried to do that.” And succeeded.

“Even now when people think of Pinehurst, they think back to the fist pump and him talking to Phil Mickelson,” says Dedman. “It’s something I think the golf world will never forget. It’s interesting to see people just want to kind of touch that, share that.”

They put it all together, before, during and after, with a little help from their friends. PS

Jim Moriarty is the senior editor at PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com for anything except gambling advice.