The rise, fall and redemption of Harvie Ward

By Bill Case

They were two good-looking guys peddling Lincolns for Van Etta Motors in San Francisco in the mid-1950s. But to label Harvie Ward and Ken Venturi car salesmen would be like saying Elvis Presley was a soldier. In 1956, Ward, age 30, and Venturi, 24, were better known as the two finest amateur golfers in America.

Like many leading amateurs of the day, Ward and Venturi were disinclined to pursue the grueling life of a touring professional. The thought of driving bone-numbing distances to far-flung tournaments playing for paltry prize money offered little attraction. Far better to enter an occasional tournament while still earning $35,000 a year at the dealership, working mornings and playing afternoon matches at California Golf Club, Cypress Point or San Francisco Golf Club. According to Venturi, “If you weren’t going to buy a car from us by noon, you weren’t going to buy a car from us that day.”

The convergence of these two stars at the dealership was no coincidence. It was engineered by Van Etta Motors’ wealthy and flamboyant owner, Eddie Lowery, a noteworthy figure in golf for nearly half a century. It was pint-sized Eddie who, at age 10, caddied 20-year-old Francis Ouimet to a playoff victory over Harry Vardon and Ted Ray in the 1913 U.S. Open at The Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, kickstarting America’s love affair with golf.

The diminutive Lowery became a fine player in his own right, capturing the 1927 Massachusetts Amateur. After moving from the right coast to the left, he partnered with Byron Nelson to win the Bing Crosby National Pro-Am in 1955. Capitalizing on his associations with Ouimet and others in the USGA hierarchy, he was appointed to various golf administrative posts, including the powerful USGA Executive Committee.

Lowery was not merely a golf Brahmin, but a business mogul, too. He built Van Etta Motors into the largest Lincoln-Mercury dealership in the country. Lowery carried a soft spot for the Bay Area’s talented young players and, in 1952, he arranged for Venturi to play with Nelson, a five-time major champion. After Venturi graduated from college in 1953, Lowery hired him to join the dealership’s sales force. Months later, figuring the presence of two star golfers working the showroom would draw car-buying sports fans in droves, Lowery enticed Ward to quit his stockbroker position in Atlanta and come west with his wife, Suzanne.

The easygoing Ward possessed salesmanship skills that would have brought success if he had never picked up a club. He seemed to like everybody, and everybody liked him — male and female. With his sweet Eastern Carolina drawl, the preternaturally relaxed Harvie was the smoothest of smooth talkers, melting buyer resistance with gentle humor.

Lowery was justifiably proud of his two employees, and bragged they could beat any two players in the country — amateur or pro — in a four-ball match. His bet was called in February 1956 by oil and mining tycoon George Coleman at a Pebble Beach soiree prior to Bing Crosby’s annual “clambake.” Coleman and Lowery each ponied up $5,000. The slick oilman had persuaded a pair of Texans to oppose the two salesmen: Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson.

Arrangements were hastily made for the match to be played the following morning at Cypress Point. Ward and Venturi, both bleary-eyed, barely made it to the first tee to face their idols. The game featured a blizzard of birdies by all participants. Hogan, who purportedly muttered on the final green that he was “not about to be tied by a couple of damn amateurs,” holed his birdie putt to win the match 1 up. The Hogan-Nelson team shot a collective 57, besting Ward-Venturi by one shot. It was the only time the car guys ever lost.

Their great play in the historic encounter seemed to inspire both Ward and Venturi to greater heights in ’56. In August, Ward successfully defended the U.S. Amateur championship he had won in dominating fashion in ’55. His resume already included the NCAA individual title in ’49 when he was an undergrad at the University of North Carolina, the British Amateur in ’52, and the Canadian Amateur in ’54. Venturi, a Bay Area product who had twice won the prestigious California State Amateur, would finish runner-up in that April’s Masters and later beat Ward 5 and 4 in front of 10,000 spectators in the finals of the San Francisco City Championship. Ward was the defending champion, having assumed the title while Venturi (who previously had won the championship twice) was away fulfilling his military obligation. When they shook hands on the first tee Venturi said, “Harvie, I’ve come to take my City back.”

Venturi’s heartbreaking final round of 80 in the ’56 Masters dashed his golden opportunity to capture the green jacket as an amateur. He abruptly turned pro and left the dealership at the end of the ’56 season and enjoyed immediate success on the PGA tour, winning twice in his rookie year and three more times in ’58. Adamant about retaining his own amateur status, Ward remained with Van Etta Motors and looked forward to the ’57 season, hoping to become the first player to win three consecutive U.S. Amateur championships.

But first, Ward would make his April pilgrimage to Augusta to compete in the Masters. In his initial appearance in 1948, he had conspicuously pulled onto Magnolia Lane with a string of tin cans trailing his tan Ford convertible and a painted sign on its side reading “Masters or Bust.” Despite this prankish debut, the event would come to hold special significance for Ward. During his stockbrokering days in Atlanta, Ward forged a relationship with Augusta National’s chairman and founder Bobby Jones, whose law firm was located in the downtown building next door to the one where Ward read the stock ticker. Ward often stopped by to talk golf with the legendary Grand Slam champion and they became good friends.

Having never turned professional during his own playing days, it was Jones’ fondest wish that an amateur might win the Masters. During the mid ’50s, among those who stood a chance were Ward (who finished eighth in 1955), Venturi, and Billy Joe Patton, another North Carolina product who narrowly missed winning in 1954. Ward later told a friend that Jones, whose debilitating spinal disease claimed his life in 1971, once intended to appoint the first of those three to win the Masters to be his successor as Augusta National club chairman.

Ward had his best opportunity in the ’57 Masters. Through three rounds, he stood just one shot behind tournament leader Sam Snead, tied with Arnold Palmer. On Sunday he was paired with short game wizard Doug Ford, who went on a sensational run, vaulting to the lead. Ward was still near the lead with four holes to play. On the 15th, Ford, the former pool hustler, went for the green with his 4-wood second. The shot smashed into the bank of the fronting pond and popped onto the putting surface. Ward’s attempt to reach the green found the water, drowning his hopes. His fourth place finish, behind Ford, Sam Snead and Jimmy Demaret, further cemented his standing as one of the game’s premier players.

Ward anticipated more highlight reel achievements to come. He was frequently mentioned as one of the favorites in the upcoming U.S. Open at the Inverness Club in Toledo, Ohio. He stood a good chance of being named the U.S. Walker Cup captain for the ’57 matches — a rumor that USGA President (and Pinehurst friend) Richard Tufts did nothing to dispel. And he liked his chances for a three-peat in the U.S. Amateur in August at Lowery’s old stomping ground, The Country Club.

Arriving in San Francisco after visiting Hogan’s Fort Worth, Texas, clubmaking facility, Ward found himself surrounded by a pack of frenzied reporters. Someone showed him a newspaper headline, “Harvie Ward’s Amateur Status Questioned.” Blindsided, Ward struggled to make sense of it. Was he in trouble?

He was. And so was Lowery.

The state of California had indicted Lowery for tax evasion, and it had been established in grand jury testimony that the auto dealer had claimed business deductions for reimbursing Ward’s expenses at tournaments like the Masters and Canadian Amateur. The USGA’s rules of amateurism prohibited a player from accepting help with tournament expenses from anyone outside his own family. It was further alleged Lowery had funded Ward’s overseas excursion to the 1952 British Amateur, well before the latter had moved to San Francisco.

The rules did provide a potential safe harbor. If a player could demonstrate that his tournament play was coupled with a legitimate business trip, he could accept reimbursement of expenses provided those related to the golf part of the trip were borne personally.

Many amateurs drove through this loophole as if it were the size of the Holland Tunnel. For years, Frank Stranahan, son of the owner of Champion Spark Plugs, received reimbursement by Champion while competing in far-flung golf events by scheduling visits to local auto repair shops. Golfers holding licenses to sell insurance were particularly well positioned. A sales pitch or two to a fellow player or official could arguably merit reimbursement for a lengthy hotel stay and more than a few good meals.

Since the rule had been honored more in its breach than in its observance, Ward assumed nothing too serious was going to happen at the USGA board hearing set for June 7 in Golf, Illinois. Furthermore, he had conducted business at tournaments. “Wherever I went I met with businesspeople and usually sold them a few cars,” he later said. “That was, after all, my job.” In addition, Lowery, a USGA board member, had regularly assured Ward the reimbursements were proper. Even if a technical violation had occurred, how could Ward be blamed for trusting his employer — a revered member of golf’s establishment?

Ward’s friend and mentor Richard Tufts was rumored to be sympathetic and would preside at the hearing. When the proceedings got underway, Harvie sensed he was in for a rough ride when Tufts failed to look him in the eye. His premonition proved correct. The board categorically rejected Ward’s arguments and ruled that his receipt of Lowery’s payments violated the USGA rules governing amateur status.

Ward later acknowledged he was “numb with disbelief” that Tufts had failed “to speak up on my behalf.” But in retrospect, it was probably naïve for him to assume that Tufts would be lenient. As author of The Creed of the Amateur, Tufts supported an idealistic (and perhaps unrealistic) vision of how amateur golfers should conduct themselves. Though undoubtedly saddened by the whole affair, Tufts never wavered from wholehearted endorsement of the board’s finding.

Ward was suspended from USGA amateur competitions for one year. His quest for a third consecutive U.S. Amateur victory had, by fiat, met a premature end. The board did not vacate Ward’s previous victories in the championship, reasoning that his reliance on Lowery’s advice, while misplaced, mitigated his offense. Still, Ward felt singled out for punishment. “If I wasn’t the amateur champion at the time, it would have gone right by the boards,” he later said. “Nobody would have cared.” Had he followed Venturi’s path and joined the play-for-pay ranks, Ward would likely have circumvented the entire debacle. Why didn’t he turn pro? “To come anywhere near what I was making,” he said, “I would have had to finish in the top five money winners.”

Many observers thought the outcome unjust. Absent outside help, how could any top-ranked amateur — except the wealthiest — afford the travel and other costs attendant in playing prestigious events around the country? In an effort to douse the firestorm, USGA Executive Director Joe Dey authored an opinion piece in the USGA Journal that struck some as breathtakingly sanctimonious. “If a young man can’t afford to play tournament golf,” wrote Dey, “he is better off not living beyond his depth. Prominence in sports can be a false god.” Tufts’ effort to clean up the amateur game actually resulted in its diminishment. The best young players, golfers like Jack Nicklaus, began vacating the amateur ranks in droves immediately after college.

Ward’s amateur status was reinstated in 1958, but he clearly was not the same player. Though he managed to present his usual blithe front, his zest for the game had waned. The stigma of the suspension had taken its toll. In ’58, Ward played poorly in the Masters and got knocked out of the U.S. Amateur in the third round. He fared little better in ’59 but did manage to squeeze onto the U.S. Walker Cup team, which included Nicklaus. Competing over The Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers’ majestic Muirfield links, Ward prevailed in both of his matches against the home team. Those wins were the 33-year-old’s last hurrah on the big stage.

After 1962, Ward drifted away from competition altogether. He declined to enter the U.S. Amateur and rejected several Masters invitations. “Basically, I said, ‘To hell with it,’” he told Golf World’s Dick Taylor. “I sort of said that I’d show those guys by not playing anymore. Kind of silly, I guess. I took up tennis, played some social golf, and went about making a living.”

Following the suspension, Ward and Lowery (who was ultimately acquitted of the tax evasion charges) started an auto leasing company together. It lasted five years. “Lowery made me a partner, gave me shares in the company, did a lot of things to sort of make up for what happened,” recalled Ward. After Lowery and Ward’s partnership ended, Harvie formed another leasing company with Bob Varner, but that broke up as well. Ward’s golf decline and business misfortunes were accompanied with, and probably exacerbated by, heavy drinking and a roving eye. After he and Suzanne divorced, he blitzed through relationships, eventually marrying five times.

In 1972, when Ward was 47, friends from San Francisco G.C. persuaded him to, at long last, turn professional and try his hand on the minor league mini-tour in Arizona. “I couldn’t beat those kids,” he said. “I made some money . . . but I wasn’t going to beat anybody.” In 1973, Ward entered the PGA Tour’s qualifying school, but it was too late for a comeback. He came nowhere close to getting his card. Later competitive efforts on the Champions Tour were similarly unsuccessful.

Ward was reduced to working in a San Francisco shipyard and teaching in a downtown sporting goods store. Mired in increasingly dire circumstances, he reached out to old UNC buddy Harvey Oliver for help. Oliver put Ward in touch with entrepreneur Dan Thomasson, one of the developers of the Foxfire Golf and Country Club near Pinehurst, who offered a lifeline by hiring Ward as Foxfire’s director of golf. The West Coast transplant, son of a Tarboro, North Carolina, pharmacist, returned to his native state.

The Pinehurst area held fond memories for Ward. He had played golf there frequently while a student at UNC and later, during his first post-graduation job selling insurance in Greensboro. Ward’s sensational performance in the 1948 North and South Amateur Championship, contested over Pinehurst No. 2, had brought the happy-go-lucky college senior his first dose of national attention. Entering the event on a whim, the unknown 22-year-old surprised himself by reaching the final, dispatching Wake Forest’s Arnold Palmer along the way.

Ward faced an uphill battle against the “Toledo Strongman” Frank Stranahan, who’d been runner-up in both the Masters and the British Open in ‘47. His secret weapon was the Zeta Psi fraternity, whose members scattered throughout the campus the night before the 36-hole final, spreading news of the match, urging students to head to Pinehurst to root for their fellow Tar Heel. Hordes of them showed up. An exuberant crowd of 2,000 overwhelmingly supported Ward. “Every time Frank would miss a shot or miss a chip, they’d cheer,” remembered Ward. “Anytime I’d get the ball airborne, they’d go nuts. You’d thought they were in Kenan Stadium at a football game.”

Ward’s stupefying avalanche of holed putts annoyed Stranahan more than the boisterous students. When he rammed home one final dagger on the 36th hole to close out his frustrated opponent, the elated Zetas celebrated by hoisting the winner to their shoulders and carrying him off the course.

Now, approaching middle age, Ward arrived at Foxfire to labor as a club teaching pro, instructing duffer and scratch player alike. His gentle manner and uncomplicated instructional method worked wonders for his pupils. When he wasn’t on the lesson tee, Ward kept his game sharp in afternoon money games with the area’s better players. The action honed his game to a semblance of its old form. At age 51, he won the North Carolina Open.

In Jim Dodson’s book A Son of the Game, Ward said that Foxfire was “where I began to finally discover what I may have been put on Earth to do. I was here to have fun playing golf with my buddies and teach others how to play this crazy game. I was here to pass the game along.”

Ward brought his charming rogue persona with him to Foxfire. Tony McKenzie, an occasional golf partner, recalls the time Ward — who was either between marriages or about to get out of one — showed up at McKenzie’s printing business asking that a batch of cards be made up reading something to the effect of, “Hello, I’m Harvie Ward. You look adorable. I’d like to get to know you better.”

After 10 years at Foxfire, Ward was hired by Nicklaus to be the director of golf at Jack’s Grand Cypress Resort, where he became Payne Stewart’s instructor. A couple of years later, Ward moved across town to Interlachen Country Club. It was in Florida where he met the woman destined to become his fifth (and final) wife, Joanne Dillon. After the couple married, they contemplated relocating. “Harvie suggested we go to either the West Coast or North Carolina,” remembers Joanne. “I said no to the West Coast. We’ll go to North Carolina.”

The couple moved to Pinehurst in 1989, settling in a spacious home on Blue Road in the village’s Old Town section. Peter Tufts (Richard’s son) constructed a par 3- hole on the property, where guests at Ward cocktail parties invariably gravitated with wedges in hand. Joanne bought her husband a 1967 Silver Shadow Rolls Royce, which he happily motored to his newest teaching gig at Pine Needles Lodge and Golf Club. He taught female attendees at Peggy Kirk Bell’s Golfaris and gave individual lessons, too. A young Webb Simpson was a pupil.

Ward’s growing reputation as a teaching pro culminated in the PGA of America naming him “Teacher of the Year” in 1990. Ward explained that the combination of Joanne and Pinehurst finally brought him peace. “That turned out to be the smartest decision I ever made,” he confided to Dodson. “Without Joanne, see, none of this would have happened. I would have been dead years ago.”

And Ward was having more fun playing golf than he had since his championship days, hooting and bantering with a disparate band of playing partners including local pros Andy Page, Bill Clement, Buck Adams and Waddy Stokes. Much of it was played at his new club, Forest Creek Golf Club. Usually, Ward took Page, the retired Southern Pines Country Club pro, as his partner. The duo would take on all comers provided that both men, sliding into their 70s, were allowed to play from the middle tees. With that advantage, they seemed as unbeatable as Hogan and Nelson. “We would make a birdie and were sure we had the hole won when either Harvie or Andy would chip in,” reflects Chris Israel, Forest Creek’s assistant pro at the time, shaking his head in disbelief. “They would drive to the next tee cackling and giggling with each other, and say loud enough for us to hear, ‘They really thought they had us. They should know better!’”

Notables from far and wide journeyed to Forest Creek to play golf with Ward. Dick LeBeau, one of pro football’s greatest defensive minds and a near-scratch player, was among them. The coach admired Ward’s ever-keen competitive nature. “He had that gleam in his eye. He knew he was going to beat you; you knew he was going to beat you; and it was fine because it was such a privilege to play with him,” reflects LeBeau. Watching ‘Ol’ Harv’ hit an iron shot was a mesmerizing experience. “It was the timing of his swing, and the sound,” marvels LeBeau. “So flush, and the ball never left the pin.”

By 2003 Ward’s freewheeling younger days had taken their toll. Diagnosed with cancer, his prognosis was not good. When asked by a friend how he was doing, Ward replied, “I’m on the back nine and I can see the clubhouse.” Several of his concerned golfing friends arranged for him to make a few sentimental journeys to golf meccas like Pine Valley and Seminole.

Jeff Dawson, a young Forest Creek member, escorted Ward to historic Merion Golf Club, where Ward’s friend Bob Jones had completed his Grand Slam. Ward was playing miserably and laboring in Philadelphia’s summer heat when the twosome reached Merion East’s 14th tee. A flock of members had come from the clubhouse to watch him play. Ward came alive, blasting a drive. That was followed by a laced 3-wood to the green and a holed birdie putt.

“What came over you?” asked Dawson.

The winking champion responded, “Those folks just wanted to see Harvie Ward.”

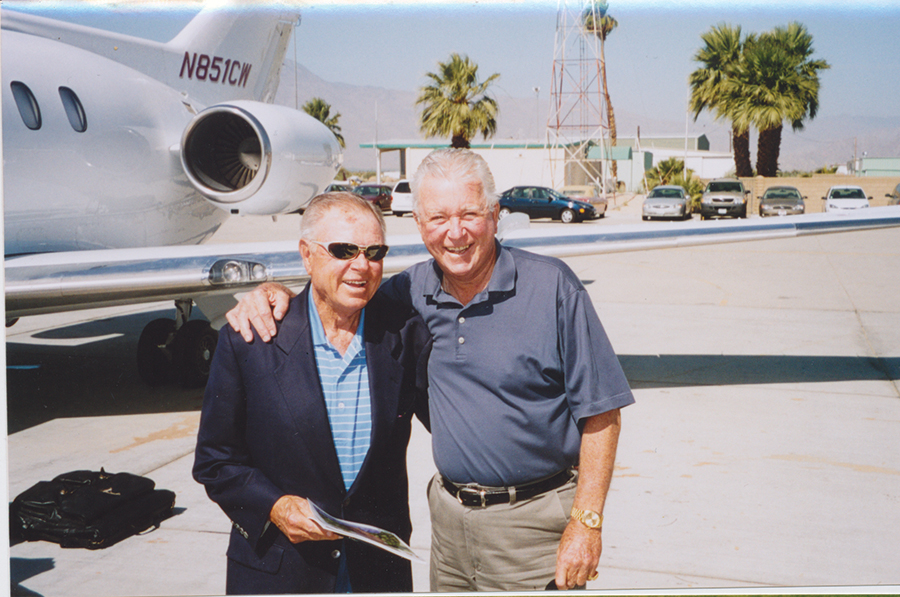

With just a few months to live, Ward and three friends (including Dawson and Ward’s personal physician) flew to the West Coast for a last golf trip. Tee times were scheduled at two of his favorites, San Francisco Golf Club and Cypress Point, where he and Venturi had carved out a portion of golfing lore 47 years earlier. On the way back East, the men stopped in Palm Springs to visit his old partner and friend, Venturi, in his desert home.

The 1964 U.S. Open champion’s den was loaded with trophies from his playing days. The one Venturi chose to place front and center was from the 1956 San Francisco City Championship, causing a flurry of good-natured teasing. Venturi took Dawson aside and said, “Do you know how good he was? I never saw him hit a 4-wood outside 10 feet!”

When it was time to leave, neither of the old running mates displayed out-of-the ordinary emotion as they hugged their goodbyes, but both realized they would not see one another again. Ward would pass away on Sept. 4, 2004. Furman Bisher, the dean of Atlanta sportswriters and a fellow UNC alumnus who covered the Masters 62 times, summed it up this way: “Harvie never lived an unpleasant day in his life or, if he did, he didn’t show it.”

Not long after returning from his final California trip, Ward played the last nine holes of his life with Dawson at Forest Creek. He shot 34 and called it a day.

“You can’t quit. You’re two under,” Dawson said.

“Yeah,” replied the rueful champion, “but nobody cares.”

His friends did. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.