A son’s moving remembrance of his struggle to win the love of a father whose emotions were as strange as the life he led

By Charles Price

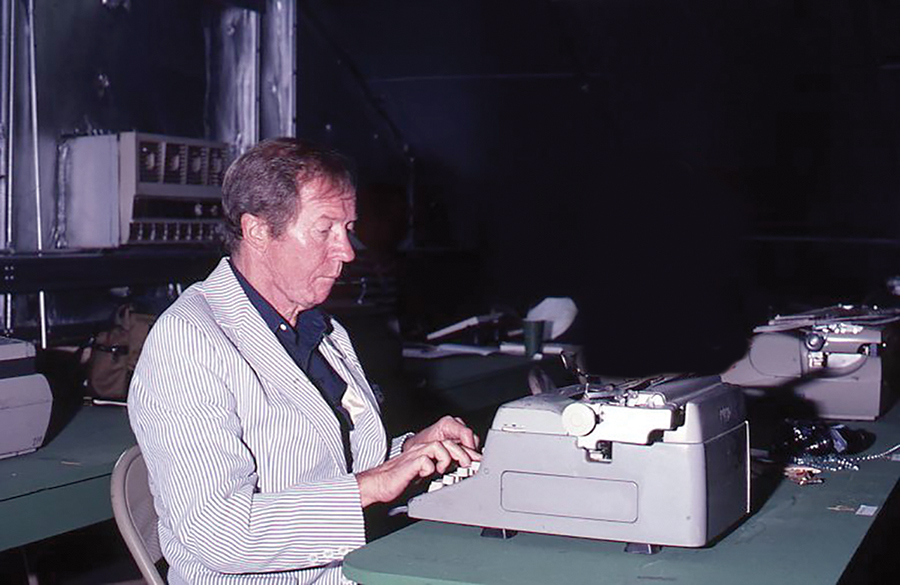

Charles Price was one of the greatest golf writers of the 20th century. I don’t know if he was at the very top of the mountain, but I do know he always worked above the tree line.

When he was in his late 20s, Charley spent a year driving Walter Hagen around Michigan’s back roads trying, unsuccessfully, to get a book out of him. Years later he became Bobby Jones’ legs during the Masters tournament, tracking down people who Jones, by then an invalid and confined to his Augusta National apartment behind drawn drapes, wanted to chat with.

Price got his start at Golf World when Bob Harlow, The Haig’s onetime agent, was still alive and Harlow’s fledgling magazine was located in the old warehouse building near the railway trestle in Pinehurst. He came back to the village to spend his last days, passing away in 1994.

Charley was a heavyweight writer but a bantamweight guy, thin as a hickory shaft and standing eyeball-to-eyeball with wee giants like Gary Player. My lasting image of him is striding up the neon green hill at the back of the Augusta National clubhouse as if the ghost of Jones had just summoned him, leaning into the climb, wearing soft shoes and a double-breasted blue blazer.

Price tried to play the professional tour as an amateur, in the days when such a thing was possible. One day on the putting green, Clayton Heafner — a very large man — said to him in his cozy North Carolina drawl, “Charley, have you noticed anything about the boys out here? Most of them are built like truck drivers with the touch of a hairdresser. You, on the other hand, are built like a hairdresser with the touch of a truck driver.”

Charley enjoyed telling that story, not so much because it was about him but because, I think, he admired the way Heafner put it together. He was kind to young writers, this young writer anyway, but didn’t suffer fools gladly. In that respect, he was very much like the man he writes about in this story, his father, published in the April 1959 edition of Coronet. — Jim Moriarty

My father was a gambler — a professional gambler. Among the people who came to his funeral were an ex-prizefighter, a strip-tease dancer, a millionaire, a cab driver, a farmer, a police captain, a nightclub comedian, our maid, a Sicilian with tattooed hands, and a bookmaker who couldn’t stop crying. There was also a man my father had once punched in the jaw.

I was surprised not at all that this man came to pay last respects to my father. I suspect he sincerely liked my father despite the fact he had once been humiliated by him. It was one of the oddities of my father’s life that everyone was always slightly terrified and mystified by him — even those he loved. I know I was. He was as inscrutable as the king of spades. I never really knew him until he was dead.

On the desk in front of me as I write is a photographic portrait of my father. I haven’t the remotest idea what he might have been smiling about. I was never very sure of anything about my father. We spent the better part of our lives together playing poker for our emotions, neither of us daring to tip his hand.

During the 1920s, when I was born, my father had operated backroom casinos in Philadelphia and Atlantic City. Before that, he had been a bookmaker. (When my mother first got to know him, she had been under the impression that he was in the publishing business.) And before that, a croupier, a bartender, and a number of other things he refused to discuss about his younger years in downtown Philadelphia.

During the last 15 of his 63 years, he had been majordomo of a gambling house in Maryland, only a few feet outside the District of Columbia. It was the largest, most colorful casino between Saratoga and Havana. Of course, it was also against the law, a discrepancy to which, however, few persons paid any attention. The integrity of my father’s casino was so beyond question, even congressmen patronized it.

Many professional gamblers have declared that my father was the best card player they have ever known. He also knew everything there is to know about craps, roulette, bird cage and other games that are outside the law of most states.

He was also acquainted with every notorious hood, cheat and racketeer on the East Coast, and he was afraid of none of them. He was accustomed to being entrusted with large amounts of other people’s money. He always kept his mouth shut about other people’s affairs. And he was scrupulously honest.

These were the qualities that set him apart from ordinary gamblers, and that enabled him to walk the underworld, if need be, with no more armor than his pinstriped suit and the incongruously flamboyant neckties he always wore.

From the time I was a little boy I was aware that my father was a man apart, not only because he was my father but because he was a creature of peculiar habits. No other father in our neighborhood, for example, arrived home from work at dawn. Sometimes, if he were particularly tired, I would be awakened by his heavy footsteps as he climbed his way to the third-floor attic, which had been converted into a sumptuous bedroom for his strange hours of sleep. To protect him from the daylight, the room had been decorated with thick drapes and blackish wallpaper. There my father slept until noon, filling the house with his resonant snoring, which I could hear even when playing in the cellar.

My father always came downstairs to breakfast dressed in his pajamas and a splendid silk bathrobe, his eyes still half-filled with sleep and his thin hair spectacularly awry on his head, like a Hottentot’s. He never said good morning to anybody, not even to my mother. Indeed, he would not speak a word until he had been fed. His breakfast was always the same — a pint of orange juice, black coffee and a thick slice of chocolate layer cake.

As a small boy, I would sometimes sit quietly across the breakfast table from my father and stare at him, fascinated by his magnificence. When he caught me looking at him, he would stop eating and lay down his morning newspaper. Peering over his reading glasses at me, he would say, not unkindly, “Is there something you want?”

I would shake my head and then scamper off, embarrassed. My father would shrug his shoulders and then go back to his breakfast.

When my father went to work, he would put on his overcoat and a large fedora, whose brim he kept rolled upward, like a Homburg. Then he would light a cigar, puffing vigorously to get it burning. Just before he reached for the door, he would blow out a cloud of smoke so thick that it would hang in the air long after he had left. As he grabbed the doorknob, he would turn to my mother and me. “Well … ” he would say, and mumble something, which we had to assume was a goodbye. Then he would close the door behind him without another word, climb into his black car and roar off to work, not to be seen again until the following noon.

My father’s favorite form of recreation was the legitimate theater. A well-performed tragedy could leave him transfixed. At a performance of Death of a Salesman, my mother once told me, my father actually burst into tears. I was astonished to learn of this, because I felt sure at the time that in real life my father would have considered Willy Loman a fool.

After an accident I had when I was 13, my father failed to visit me in the hospital. Despite the many logical excuses my mother made for him, I was bewildered and hurt. Today I know that he didn’t come because he couldn’t bring himself to see me hurt.

My father never wrote a letter to me in his life. If he had, it would today be framed and sitting on my shelf. Correspondence between us was handled by my mother, who wrote at length to explain the many fond thoughts my father had of me when we were separated, thoughts he somehow couldn’t bring himself to express when we were together.

My father lavished gifts on me, but to my knowledge he never personally bought me any of them. He considered the giving of presents unmanly. But he could periodically give $10 tips to a blind news dealer. (I doubt that he could have given them to a man who could see him do it.) He could send $100 — anonymously — to a lifeguard who had rescued somebody. And he could send a girl, who had been disfigured for life in an automobile accident, through college without ever letting her know he had paid the bills.

To this day I meet strangers who, on learning whose son I am, tell me stories of my father’s extraordinary generosity. It will always be a mystery to me, however, how a man could be seemingly so generous yet be so parsimonious when his emotions were involved. While during all my father’s life he remained to me — and still remains to me — as heroic as a father should be, we were in truth as uncommunicative as a father and son could be.

When I was 12, for example, my father sent me to a golf professional at a nearby country club. “Teach him everything there is to know about the game,” he said. His instructions to me were just as simple: “Call all the members ‘mister.’”

When I was 13, I played in my first tournament. I won it, but my father did not congratulate me. He bought me a new set of clubs, instead. I have since played in more than 100 tournaments, but my father watched me play in only one that I can recall.

I saw him standing behind a tree overlooking the fourth fairway. Because the match was a final, it had attracted a small gallery. While it is not uncommon for spectators to stand within a few feet of a contestant, my father wouldn’t come within 100 yards of me. At the end of nine holes, I was two-down. My father got into his black car and drove away. I don’t know whether he felt his presence was making me self-conscious or that he couldn’t bear to see me lose.

When I arrived home, I found him pacing back and forth on the driveway. “Well?” he said.

“I won,” I answered.

At that, my father reached into his pocket, pulled out a roll of bills, and then peeled off a $50 note. “Here,” he said. He handed the $50 to me and then he turned his back, so I wouldn’t see the pride on his face. He wanted dreadfully to congratulate me, but he just didn’t know how. While his manner may have seemed heartless, it wasn’t. My father was willing to be a father, but he refused to act like one.

When I was graduated from high school I was given a watch which I purchased myself with money my father gave me. Childishly perhaps, I was disappointed that he had not purchased the watch for me himself.

After high school, I attended two different colleges. My father visited neither one, not even on the day I was graduated. Since nothing had been said about his attending the exercises, I didn’t bother going myself. My diploma was mailed to me. When it arrived, I showed it to my father. He glanced at it, and then he told me to go downtown and buy a car for myself. For a moment, I thought I hadn’t heard him correctly. The tone of his voice was so matter-of-fact. You might have thought he was asking me to go down and buy him a cigar.

I am certain that my father was proud of me. I am positive he loved me. But it was our misfortune that we could not bring ourselves to exchange this information.

When my father was drawing close to death, we arranged a bed for him in a second-floor living room. One evening when I was alone with him, he sat up and said, bluntly, “I’m dying,” and he looked straight into my eyes. I couldn’t answer. My father swore softly under his breath, then lay back in bed.

All that night, I held my father’s hand. A croupier from my father’s casino gave him his medicine and wiped his brow. Near dawn, I climbed to my father’s attic and threw myself exhausted on his bed.

While lying there, I knew for the first time just why I loved this man to whom even the ordinary signs of love had always been embarrassing. I understood then how unselfish he had been in never trying to mold me in his own image, unlike so many fathers who act the paternal role to its fullest.

I saw, too, that despite the fact his life had been carried on outside the pale of ordinary society, he had always conducted himself with personal dignity. I decided that when I awoke I would somehow force myself to tell my father how much I loved him. Our lives together had been largely spent trying to divine each other’s feelings, and I had grown weary of the game.

I had been asleep about two hours when the croupier aroused me. “Wake up!” he said, shaking me. I sat up in bed and rubbed my eyes.

“You’d better come downstairs,” he said quietly. “Your father’s dead.” PS