SPORTING LIFE

The Gift of Time

Planning new adventures

“The best thing about hunting and fishing, is that you don’t

have to actually do it to enjoy it. You can go to bed every night thinking about how much fun you had twenty years ago and it comes back clear as moonlight. It is a kind of immortality, because you’re doing it all over again.”

— Robert Ruark’s Africa

By Tom Bryant

I had been thinking right regularly about mortality and immortality, having been recently diagnosed with cancer. The folks at Duke University performed their miracle, and on my latest scan and workup the cancer had disappeared. When I asked the doc about limits I might have, she replied, “Nothing, you can do whatever you were doing before all this came about.” Naturally Linda, my bride, and I rejoiced, and on the way home from Duke, I was like a kid the day before Christmas.

That night as I was relaxing by the fire reading some old columns I had written years before, I determined that the plan for the immediate future was to categorize things I wanted to do in the field, and things that Linda would enjoy doing with me. I grabbed a yellow legal pad from my desk, and I was off and running.

The musings I had made years before when I was in my prime, climbing over obstacles rather than going around them, got my list started with a flurry.

Ages ago, it seems like, I used to goose hunt, Canada geese, that is. It was before the geese that migrated every year realized they really didn’t have to do that. The ones that used to come down from the frosty North and set up camp in the sunny South would lounge around enjoying all that fresh grass recently planted on golf courses and the fields full of winter wheat just ripe for the picking. But then spring and a little warmer weather would roll around, and it would be time to pack up and wing it back north.

I don’t know how it happened, but I can imagine it went something like this: A couple or three geese were lolling about munching lunch on the 14th green when one of them said, “Well, it’s about time to hit the road back to the old homestead.”

Another of the geese, maybe one with a little more mileage on him, spoke up. “Boys, I’ve been making that trip more times than you are old, and I just made up my mind that I’m gonna stay here this summer. Why do all that flying and wandering about when we have everything we need, plus some, right here? Y’all have a nice trip and I’ll see you next winter.”

Thus it started. Wild Canada geese that were as skittish as bobcats overnight became residents and all but demanded their entitlement — fresh grass for everyone.

That’s what’s happening now. What I wrote about in those aged scribblings that dotted outdoor magazines and sporting pages in newspapers was when the noble Canada goose was a worthy game bird, worth all the notoriety given.

Every January, for about eight or 10 years in the late ’70s and early ’80s, my good friend Tom Bobo and I would head to the Eastern Shore of Maryland and the little town of Easton to goose hunt on the famous Plimhimmon plantation, located on the Tred Avon River close to Oxford, Maryland. The owner was a crusty old guy by the name of Bill Meyers. His land was about 400 acres with the river on one side and an estuary off the Chesapeake Bay on the other. It was as if it was made for goose hunting. We were in high cotton, so to speak, in those days, hunting with the likes of such notables as Bing Crosby, Ted Williams and Phil Harris.

So how can I follow up those ancient days of classic goose hunting in these modern times? Easy, first thing to do is head to Easton and get the lay of the land today. Then the plans will follow.

I made a few notes on my pad and moved on to the next adventure.

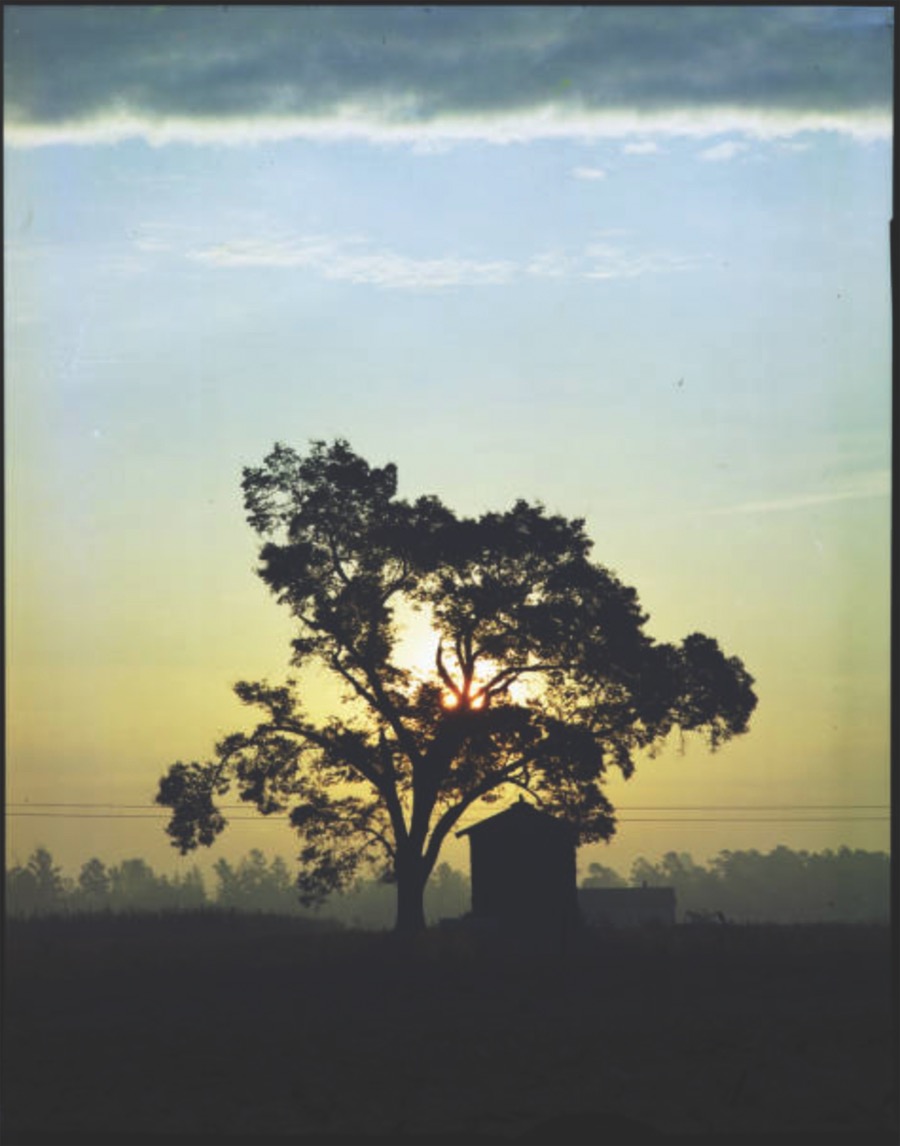

When I was a youngster growing up in Pinebluff, I had the best of all worlds as far as outdoor living was concerned. If not camping with the Scouts from old Troop 206, I was scouting on my own, finding likely places to explore. I would hook my Red Flyer wagon to my bicycle, loaded with camping gear, and head to the woods.

That was my first experience pulling a trailer, and I never forgot it. Decades later, the year I retired from my day job, Linda and I bought a little compact Airstream Bambi travel trailer, hooked it up to a Toyota FJ Cruiser, also new that year, and started the trip of a lifetime. Where to? North to Alaska, of course. We were on that special adventure for two months and drove over 11,000 miles.

Since that first epic experience, we have towed and camped in the Bambi several times across the country and to Florida during the winters. In Florida we would camp at a small scale campground on Chocoloskee Island, just south of Everglades City. Linda called it our fish camp.

In the summers we tried — and were usually successful — to camp at Huntington Beach State Park in South Carolina one week out of every month.

I made a few more notes on my pad, put another log on the fire and thought about what it would take to get the little “Stream” back on the road. Not that much really. A detailed check at the Airstream place in Greensboro, maybe a new set of tires, then rig her for running sometime in the late spring.

Linda had gone on to bed and I was ready to hit the hay myself, so I banked the fire to be ready for the next morning and quietly moved down the hall to bed trying not to wake her. Lying there snug under the covers, I thought back over the last year-and-a-half.

Cancer puts a hold on everything. Every day during my experience with the disease we waited for the other shoe to drop, not knowing if it was going to be terminal or just debilitating. The waiting was the hard part.

But just like Robert Ruark said in his book on Africa, I’ve had a lot of experiences in our great outdoors, and thinking about them from 20 or more years ago and reliving them all over again is a kind of immortality.

Now, amazingly, the good Lord, along with the wonderful health professionals at Duke, have made it possible to continue my adventures, hopefully for a few more years. I put together a good start sitting by the fire.

I heard the ship’s clock in the den ding six bells, 11 o’clock. Time to sleep and dream good dreams.