On a Wig and a Prayer

By Jim Moriarty

When the occasion warrants, I’ve been known to dress in women’s clothes. I’m not going to blame genetics entirely for this but it’s an established fact that my eldest brother — the one with the Ivy League law degree who clerked on the United States Supreme Court — once performed a musical number in drag at a 137-year-old Boston club that, on a separate occasion, had entertained Winston Churchill at dinner. My brother did allow as how the entire affair was a bit embarrassing, though given his singing voice, I’m not sure which part would have been the most mortifying.

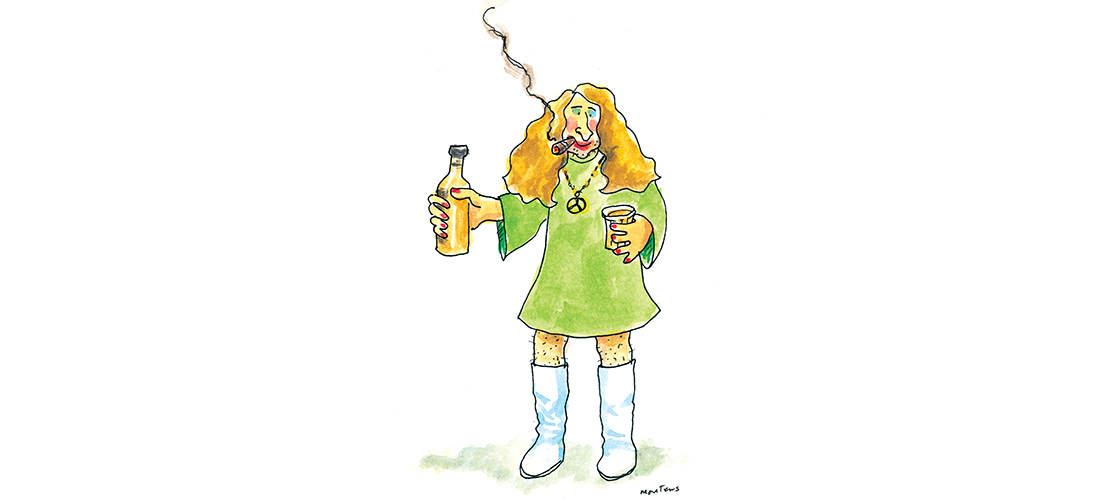

While my local club, the Bitter and Twisted, never, to the best of my knowledge, hosted a British prime minister, I have appeared behind the bar there in female costume. It may have happened more than once. One particular evening it was for a holiday fundraiser. My wife, the War Department, and I joined Doris and Neville Beamer to pour beer and mix drinks dressed as The Mamas and the Papas. I was Mama Cass.

Costuming wasn’t a significant issue. As luck would have it, Mary McKeithen at Showboat has all my measurements — though for this episode I confess broad admiration at her ability to conjure up a pair of size 10 1/2 white go-go boots, a feat she accomplished with the apparent ease of ordering a pepperoni pizza.

The evening coincided with a visit from our nephew. At the time he was a C-130 pilot on active duty in the California Air Force Reserve, and he and his crew had put in at Pope Air Force Base on their way to who knows where. We invited them to join the festivities, which they did.

When our two-hour cruise behind the bar had ended, we collectively decided to retire to Neville’s basement emporium to unwind from the demands of performance art. Unaccustomed as I was to the rigors of wearing white go-go boots, I couldn’t tolerate the pain any longer and had to make a stop at home to de-Cass before joining the rest of our jolly band. I showed up at Neville’s in my usual costume — jeans, tennis shoes, a golf shirt and a jacket. As time went by and the feeling returned to my feet, my wife was approached by one of our nephew’s crewmen.

“So, what happened to Uncle Jim?” he inquired, clearly crestfallen at the mysterious absence of Mama Cass.

She nonchalantly pointed at me several barstools away. “He’s right there,” she said. And had been for the better part of an hour.

The appearance, or disappearance, of Mama Cass wasn’t my last brush with blush. That occurred some years later when I was on tap to reprise our bartending masquerade, this time dressed as a traditional geisha.

The War Department had volunteered to apply my makeup for me. After painting my face with the appropriate white greasepaint, she began drawing on the bright red lipstick with the care and concentration of a high school biology student slicing open a frog. When she finished she stood back to admire her handiwork.

“Oh, my God,” she said, her eyes widening with fright.

“What?” I asked. What had she done? Was I fixed up to look like the Joker?

“You look exactly like your mother.”

That was enough to make me hang up my muumuus for good. PS

Jim Moriarty is the Editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.