SOUTHWORDS

Live in the Meow

Curiosity didn’t kill this cat

By Emilee Phillips

Cats having nine lives is a cliché. Orange cats being a menace is another. But my childhood cat, Simba, fits the bill for both.

He was trouble from Day One. We found him abandoned under an azalea bush and roaring his little kitten head off. I had never heard such a small animal make so much noise. After capturing the terrified little guy, I discovered he also had six toes, like the Hemingway cats. Trouble.

Simba has always preferred the jungle — er, pine trees — to the cushy indoors. He roamed and picked fights, holding his own in the wild kingdom (our neighborhood). The cat was a scrapper through and through but always came when his name was called. He had a soft spot for family. Or so we thought.

When we moved to horse country Simba went along for the ride. It’s not uncommon for animals to run off after a move. They may get confused and try to find their way back to their former abode.

Shortly after we relocated, Simba disappeared. I imagined him weaving in and out of briars, riling up goats, scurrying around towering horses like a night bandit. I hollered for him daily, nightly. Not a meow was heard in response. The family searched for him but the new house was out where coyotes regularly lurked. We feared the worst.

After a couple of months, we accepted that our family cat was gone. We honored him with a framed picture that read “Forever in Our Hearts,” with the years of his life inscribed on the back.

But we were wrong. He hadn’t used up all those lives just yet.

My mother and I were shopping in Raleigh one day the next summer when she got a call. “Hi there. I’m a security guard at Penick Village. I, um, think I have your cat.”

We exchanged looks of confusion. “Is it black?” asked my mother, thinking perhaps our second cat, Zelda, had decided to visit some distant, unknown aging relative.

“No, ma’am, it’s orange.”

“Orange!” we exclaimed in unison.

“Yes, ma’am, I’ve seen him out here every night for the last few months. I figured it was a stray. He finally let me get close enough to grab him and he had a collar. Thought I would try calling.”

We zoomed back. It was dark by the time we got there, and the cat was nowhere to be seen. I stalked the retirement community for the next three days.

I asked anyone I saw outside on the street, “Have you seen an orange cat?” To my amazement, nearly all of them said, “Yes.” Great, I thought, my cat has been family shopping. No doubt capitalizing on extra rations from multiple residents. I handed out my phone number like I was passing out Junior Mints.

On the third day, I got a call. A sighting!

I rushed to Penick Village and jumped out of the car. “Simbaaaa!” I yelled. Next thing I knew I hear a “bwrrr” and out popped my cat from the bushes. I half expected it to be some lookalike, some faux Simba, but it was my very own six-toed little feline. He rolled on his back and purred, seemingly indifferent to the fact that he had been missing for 10 months.

I coaxed him with treats and, after a moment of deliberation, he sauntered over with an accusatory look as if to say, “Yo, where you been?” Once in the car, he jumped into my lap as though this was just another chapter in his great escape.

A wave of emotions rushed over me: happiness, bewilderment . . . and annoyance that my cat decided he wanted to experience an easier pace of living. Well, I was taking him out of early retirement.

The reasons for Simba’s disappearance remain a mystery, having chosen assisted living even over our previous residence. Once I got him home, he didn’t bother with the cat bed we’d set up for the return of the prodigal tabby. Instead, he flopped down on the windowsill, resuming his rightful place with a lazy stretch.

We knew at that moment he wasn’t just returning from his brief sabbatical. He was back, all the way back, ready to once again rule over his empire of pillows and food bowls, with no intention of going missing again, except perhaps to a particularly sunny patch of grass somewhere nearby.

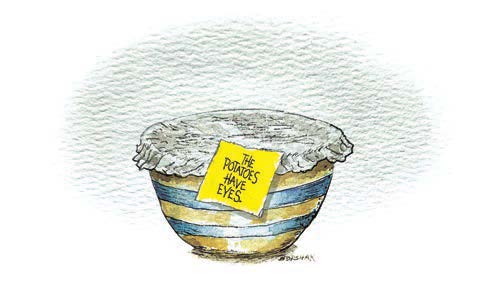

As for us, we crossed out the dates on the back of Simba’s frame and updated the picture — mug shots, front and side.