SIMPLE LIFE

Squirrelly Business

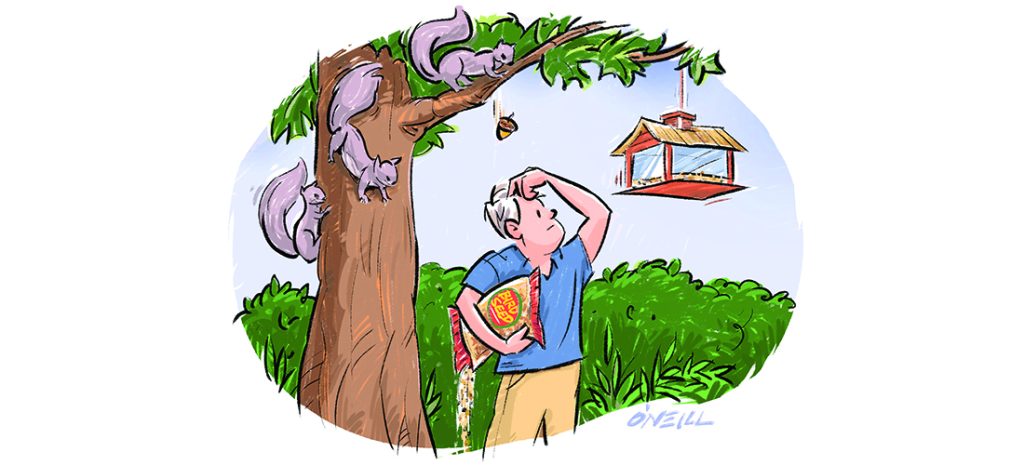

A seedy family of rodents drives an old dude nuts

By Jim Dodson

Another summer is ending.

And once again, the squirrels have won.

Last year about this time, you see, I made a promise to myself — not to mention the many wild birds that regularly visit our four hanging feeders — to find a way to outfox the large crime family of gray squirrels that inhabits Old George, the handsome maple tree that anchors our front yard.

The problem began rather innocently six years ago when we moved back to the heavily forested neighborhood where I grew up and rescued George from death by English ivy. The old tree flourished and, one afternoon, I noticed a couple gray squirrels had taken up residence in a hollow nook halfway up the tree. They seemed to be a respectable couple, perhaps elderly pensioners looking for a nice place to tuck in for their quiet retirement years. Our property is also home to several towering oaks, so come autumn there would be a plentiful acorn supply.

I hung a couple bird feeders by wires from George’s upper branches. Soon the wild birds were all over them. What a peaceable kingdom it seemed.

The next spring, however, there were four squirrels residing on Old George. Clearly, they were no elderly pensioners, for within months, two baby squirrels appeared and I found a juvenile delinquent regularly helping himself to premium birdseed, scattering it on the ground below the feeder, having somehow slid down the 10-foot wire like a paid assassin from a Bond flick.

He soon returned with two bushy-tailed pals from across the street. Word was out. Party at the Dodson house, all-you-can eat birdseed buffet, pay no attention to the old dude waving his arms and shouting obscenities.

By the next year there were at least seven or eight tree squirrels residing on Old George, a budding Corleone family of furry rodents regularly raiding the feeders, costing me a bundle just to keep them filled up. I bought expensive “squirrel-free” feeders and fancy bird feeder poles equipped with “baffles” guaranteed to keep the gymnastic raiders on the ground. These sure-fire remedies, alas, only baffled me because they posed only a minor challenge to the squirrels. So I made a deal with the big fat squirrel that seemed to be the head of the family. Whatever they found on the ground at the feet of Old George was theirs to keep. Thanks to the jays, the sloppiest eaters in the bird kingdom, there was plenty of seed for them to gorge on. For a while, this protection racket seemed to work until one afternoon as I was filling up “their” feeder, I heard a pop and turned to find the big fat crime boss squirrel dead on the ground. He’d been pushed off a high limb where two younger squirrels were looking down with innocent beady-eyed stares. Just like in the movies, a younger more ambitious crime boss was in charge.

I considered giving up and moving to northern Scotland. Instead, I asked my neighbor, Miriam, a crack gardener and bird fancier, how she handled pesky squirrels. By “crack gardener,” I don’t mean to suggest that sweet elderly Miriam was growing crack cocaine, merely that if anyone could tell me how to stem the tide of ravenous tree squirrels it was Miriam. She’d lived in the neighborhood for 40 years. She is my turn-to garden and bird guru.

Miriam thought for a moment before coming out with a chilling laugh. “They’re impossible to stop.” She pointed to her Jack Russells. “That’s why I have Jake and Spencer. They do a pretty decent job on the squirrels and chipmunks.” She admitted that she always wondered whether squirrels are the smartest or dumbest of God’s creatures. “How can squirrels be so smart they can get into any kind of bird feeder — but always stop suicidally in the middle of the street whenever a car is coming?”

It was a good question I had no time to ponder.

Our other neighbors down the block, Miriam explained, had taken to humanely trapping their squirrels and releasing them in the countryside. “But I read somewhere that if you don’t take them more than 10 miles out of town, they’ll come straight back.”

That was all I needed — country cousins joining the feast.

Next, remembering my former neighbor, Max, I actually gave thought to arming myself with a Daisy BB gun. It’s right there in the second amendment, after all — the right to bear arms against unreasonable threats from hostile elements, both domestic and foreign. True, the Constitution doesn’t mention thieving gray tree squirrels per se, but one doesn’t have to be a strict constitutional originalist to interpret the broad meaning of those historic words.

Max was my neighbor down in Southern Pines, a fabulous gardener famous for his giant tomatoes, succulent sweet corn and luscious collards. To protect his bounty from the herds of deer that roam the Sandhills, Max essentially erected a Russian-style penal colony around his veggie garden, complete with electrical voltage and 24-hour monitoring system.

The first evening I dined with Max and his beautiful wife, Myrtis, as the salt and pepper came my way on the lazy Susan, I noticed a large jar of Taster’s Choice — circa 1976 — festooned with several sheets of notepaper attached by rubber bands. The sheets were covered with dozens of dates written in tiny, neat handwriting.

“What are these dates?” I asked. “The last time you tried really old instant coffee?”

Myrtis laughed. “Oh, no. Those are dates of Max’s squirrel kills. He shoots them.”

Max just smiled. “Haven’t had a squirrel problem in years. It’s either them or my vegetables.”

I was in the presence of evil genius, a terminator of problem squirrels.

Call me a tree-hugging man of peace — Rocky and Bullwinkle were my favorite childhood cartoon characters — but I decided to forgo the gun and simply rely on Miss Miriam’s way to put the fear into the furry crime family that inhabits Old George.

Nowadays I wait until I see them climbing up poles, dangling upside down to feed or diving insanely from tree limbs onto our feeders, whereupon I strategically release our 75-pound Staffordshire pit bull and fleet-footed border collie-spaniel puppy and watch the merry chase begin. There’s been more than one narrow escape and parts of furry tails have been brought back to master of the hounds.

True, it’s not a permanent solution to the problem. But for now, Gracie and Winnie enjoy the exercise and I am sending an unmistakable message to the squirrelly Corleones.

They’d best stay out of the middle of the road when this old dude is at the wheel. PS

Jim Dodson is the founding editor of O.Henry.