By Jim Dodson

Half a century ago this month, I was chased off the golf course of my dad’s club in Greensboro for losing my cool and burying a putter in the flesh of an innocent green during my first 18 holes ever on a regulation course. To compound the crime, I was playing with my dad and his two regular golf pals at the time, Bill Mims and Alex the Englishman.

After being shown how to properly repair the damaged green, my straight-arrow old man calmly insisted that I walk all the way back to the clubhouse in order to report my crime to Green Valley’s famously profane and colorfully terrifying head professional, who upon hearing what I’d done removed the eternally smoldering stogie from the right-hand corner of his mouth long enough to banish me from the golf course until midsummer.

This felt like a death sentence because I had been preparing for this day for well over a year, wearing out local par-3 courses and modest public courses in preparation for stepping up to a “real” golf course with my dad and his buddies. The idea was that I should become reasonably proficient at playing but — more important — learn the rules and proper etiquette of the ancient game.

Painful as it was, this day, it changed my life.

The next afternoon after church, a postcard Sunday in early May, my dad drove me 90 minutes south from the Piedmont to the Sandhills to show me famed Pinehurst No. 2, Donald Ross’ masterpiece, where I saw golfers walking along perfect fairways and actually heard a hymn being chimed through the stately longleaf pines.

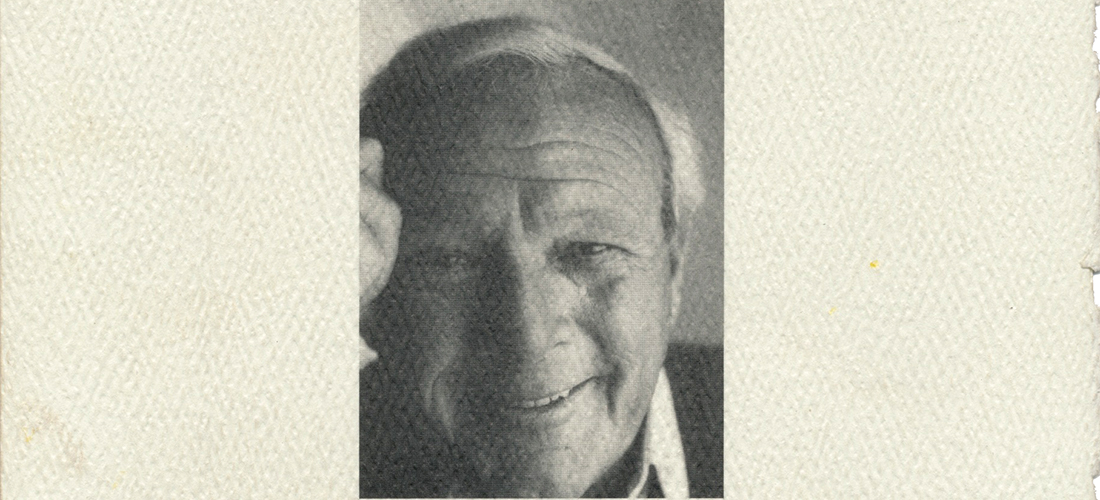

True to form, my upbeat old man — whom I called “Opti the Mystic” owing to his relentless good cheer and penchant for quoting long-dead sages when you least expected it — calmly pointed out: “That golf course, Sport, is one of the most famous in the world. But you’ll never get to play there until you learn to properly behave on the golf course.” He added, “If you ever do, you’ll be surprised how far this wonderful game can take you.”

I was crestfallen as we drove on past the famous course. But a few miles down Midland Road we turned into a small hotel that had its own golf course, the Mid Pines Inn and Golf Club. “Let’s step inside,” my dad casually suggested. “I’ll introduce you to an old friend.”

His old friend was a man named Ernie Boros, the brother of Julius Boros, the U.S. Open winner I’d recently tagged along after at the Greater Greensboro Open whenever I wasn’t shadowing my hero, Arnold Palmer.

Ernie Boros couldn’t have been nicer, offering me a free visor along with the news that his famous brother Julius happened to be having lunch at that moment in the dining room. He graciously offered to introduce us.

The encounter was brief but warm. The great man asked me how I liked golf and commented that if I continued to grow in the game, the odds were good that I would meet the most amazing people on Earth and play some incredible golf courses. Then he offered to sign my new visor.

“Wasn’t that something?” said Opti as we wandered out to look at the 18th hole of Mid Pines, which that day, wreathed with dogwoods and banks of azalea just past bloom stage, looked every bit as magical as Augusta National did on television. “You just never know who you’ll meet in golf. Tell you what,” he added almost as an afterthought, “if you think you can knock off the shenanigans, maybe we can play the golf course here today.”

And with that, I finally got to play my first full championship golf course.

It only took another two decades (and my mom fessing up) for me to realize that the whole affair was simply a sweet setup by my funny and philosophical old man — a classic Opti the Mystic exercise to illustrate the point of learning how to live life with joy, gratitude and optimism, not to mention respect for a game older than the U.S. Constitution.

And here’s the most amazing thing of all. Both men were correct in their assessments of golf’s social and metaphysical properties. If I’d been less awestruck and a little more tuned into the universe, perhaps I’d have heard echoes of the same message coming from Opti and Julius Boros — that the ancient game could take you amazing places and introduce you to some of the finest people on Earth.

A fuller account of this teenage epiphany opens the pages of The Range Bucket List, my new — and possibly final — golf book that reaches bookstores May 9. Fittingly, the memoir appears almost 50 years to the day after that life-altering weekend.

In a nutshell, the book is simply my love letter to an old game that, true to my old man’s words, took me much farther than I could ever have imagined it could, deeply enriched — and possibly even saved — my life.

It even eventually brought me home again to North Carolina.

Not long after turning 30, taking the advice of Opti to “write about things you love,” I withdrew from consideration for a long-hoped-for journalism job in Washington to relocate to a trout stream in Vermont where I went to work for Yankee magazine as that iconic publication’s first senior writer (and Southerner), a move which helped shape the values of this magazine and opened an unexpected door to the world of golf.

This move in turn led to Final Rounds, a surprise bestseller about taking Opti back to England and Scotland to play the golf courses where he fell hard for the game as a homesick soldier prior to D-Day. My dad was dying of cancer at the time. It was indeed our final golf trip.

Among other surprises, the book prompted Arnold and Winnie Palmer to get in touch, inviting me to spend two years living and traveling with them as we crafted Arnold’s own best-selling memoir, A Golfer’s Life. An enduring friendship and nine books followed, four of which were golf-related, including the authorized biography of Ben Hogan and a biography of America’s own great triumvirate of Sam Snead, Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson.

A few years back, while looking through an a trunk full of my boyhood stuff from my late mother’s house, I found my first three golf books and a small notebook that listed 11 items on my “Things To Do In Golf” list.

Here’s the list:

1. Meet Arnold Palmer and Mr. Bobby Jones

2. Play the Old Course at St Andrews

3. Make a Hole in One

4. Play on the PGA Tour

5. Get new clubs

6. Break 80 (Soon!)

7. Live in Pinehurst

8. Find Golf Buddies like Bill, Alex and Richard (my dad’s regular Saturday group)

9. Caddie at the GGO

10. Have a girlfriend who plays golf

11. Play golf in Brazil

That was it, short and sweet. If you’d have informed me when I cobbled this list together (probably the year before I got the boot from Green Valley) — the predecessor of what decades later I came to call my Range Bucket List — that I would accomplish in some form or another everything on this list and then some over the next half century, I probably would have laughed out loud in disbelief — or simply keeled over from pure glandular teenage joy.

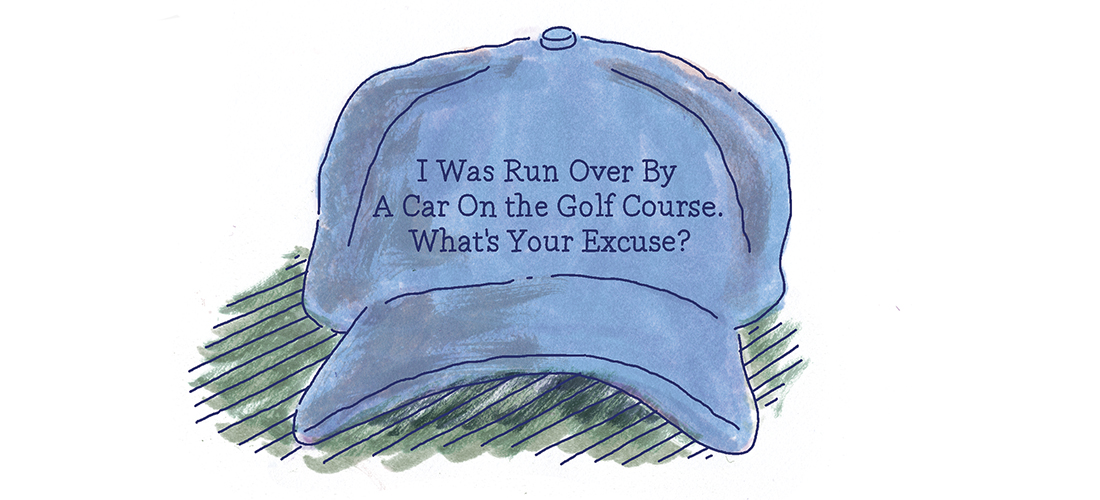

In simplest terms, that’s what The Range bucket List is, a grateful Everyman’s love poem to the finest game on Earth, tales I’ve never been able to tell until now about Arnold and Winnie Palmer, John Updike, Glenna Vare, amateur great Bill Campbell, LPGA icon Jackie Pung, the greatest Scottish woman on Earth, the power of a best friend and the ultimate mulligan at marriage, low Old Course comedy and how — true to Opti’s words — the game deeply enriched my life and even brought me safely home to North Carolina again. There’s even an oddly revealing account about a peculiar afternoon of golf with a guy named Trump.

I hope those who enjoy my books find this tale amusingly human, perhaps even reminding them of their own travels through the game of life and their love affair with a grand old game. Every golfer worth his salt, after all, keeps a Range Bucket List. And everyone’s list is different.

I’ll be making the rounds in the state throughout the spring and summer, spinning some of these tales and others I’ve never told, meeting like-minded sons and daughters of the game who share my passion for its many unexpected gifts.

Perhaps we’ll meet at one of these gatherings.

Maybe by then I’ll have even figured out why I was so hot to play golf

in Brazil, the only item from that list from so long ago, still waiting for a check mark.

The List, like life itself, goes on. That’s part of the fun, and the sweet mystery of golf. PS

The book debut! Jim Dodson will be reading from and discussing The Range Bucket List at 5 p.m. on May 23 at The Country Bookshop at 140 NW Broad Street, Southern Pines. For mor information visit www.thecountrybookshop.biz.

Contact Editor Jim Dodson at jim@thepilot.com.