Reconsidering a White Christmas

Perfection isn’t what it’s cracked up to be

By Tom Allen

The chances of a white Christmas in the Sandhills of North Carolina are slim to none. Even if a few flurries put folks in the holiday spirit, the National Weather Service defines a white Christmas as having at least 1 inch of snow on the ground the morning of December 25. But a couple of inches on December 22 that hang around for a few cold days would make the cut, right? Liturgically speaking, Christmastide is 12 days, so more days equals a greater probability, correct?

Dreaming of a white Christmas, where the treetops glisten? Bing crooned the iconic song, first heard in Irving Berlin’s classic, Holiday Inn, then later in the eponymous motion picture. It continues to be the bestselling Christmas song of all time.

The concept is lovely, but when it actually happens, the dream, more often than not around here, becomes a nightmare — wind, cold, ice, cars off the road, and sundry other unpleasantries. In our part of the world the three French hens wouldn’t have electricity.

Aside from a couple of Christmas day dustings, I’ve only experienced one white Christmas, in Louisville, Kentucky, the winter of 1990. One front after another brought several inches of snow, starting the first week of December, continuing, almost weekly, for the next three months. Snow and a couple of ice storms kept the frozen stuff on the ground until early March.

Western Kentucky is well-equipped for these seasons, unlike the more temperate parts of the South, where a couple of inches brings life to a standstill. Roads and parking lots stayed pretty clear. Even the apartment complex where I lived kept the sidewalks and entryways clean. But dirty, piled-up snow, gray mush and salty slush made for a depressing winter. And even with salt trucks and snowblowers, I often found myself waddling on an icy sidewalk or gingerly taking baby steps, hoping not to fall, which I did on a few occasions, bruising my ego more than other bodily parts.

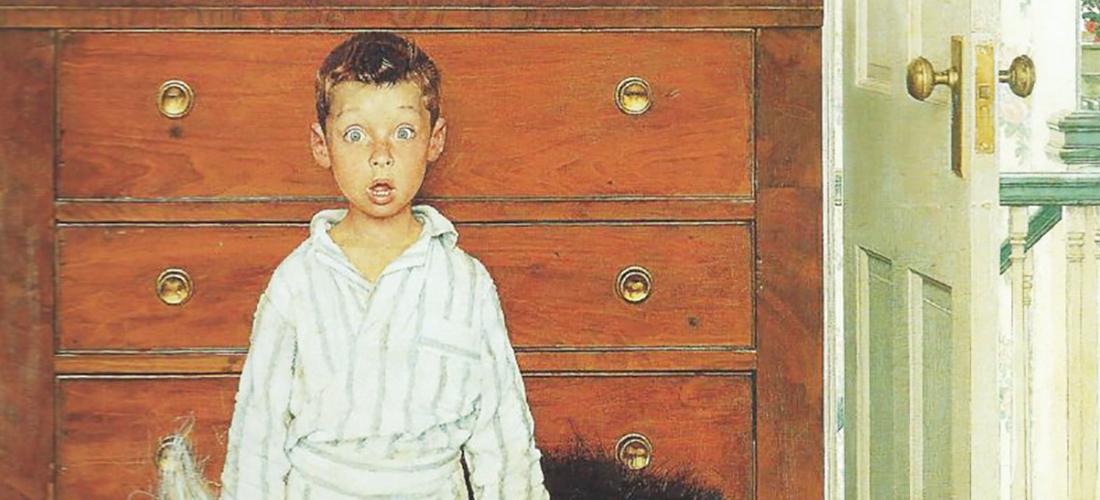

On Christmas Eve 1990, my then-fiancée, Beverly, and I headed out to a service at the church we attended. The night was cold, raw, with just enough flurries to slow driving. Inside, the setting was beautiful, traditional, candles and crèche, and “Silent Night” to wrap things up. Heading out to my car after the service I noticed a grey Buick sedan had skidded on an icy patch into the front door panel on the passenger side of my red Toyota. Before I could yell, “Hey, hold on,” the car was gone. The dent was minor; I’d like to believe the chap driving the grey Buick had no idea he bumped my car. After all, it was Christmas — peace on Earth, goodwill to men, even the ones who dent your red Toyota. My instinct was to run, to catch the fella’s attention, to wish him a “Merry Christmas” before I pointed out we needed to talk. But another patch of ice brought me down, making me wonder just how merry and bright this Christmas would be.

As I recall, other than the dent — which I never got repaired — and a sore backside, it was a pretty good holiday. Oddly, the fact that our Christmas was white mattered little. I’ll take a chilly morning, clear roads, whatever family is gathered, and a snuggle with my dog. Because the perfect Christmas, like the perfect marriage or kids or job or church, really doesn’t exist.

So, consider letting go of that perfect holiday. Substituting canned biscuits for yeast rolls that failed to rise isn’t the end of the world. What if the recycled Dollar Tree bag you had to use because you forgot that pretty roll of paper had someone else’s name on it? Don’t sweat it. Kids wiggly at Christmas Eve services? Baby starts crying during “Silent Night”? What better night to hear an infant cry?

The probability of a white Christmas here is low. Chances of a 70-degree day are the same as a 40-degree day. So be thankful for whatever’s on your table — and the people around it. Be civil. Be kind. Be glad.

Just watch out for that guy in a grey Buick sedan. PS

Tom Allen is minister of education at First Baptist Church, Southern Pines.