Untold Stories

A simple man’s jump into history

By Bill Fields

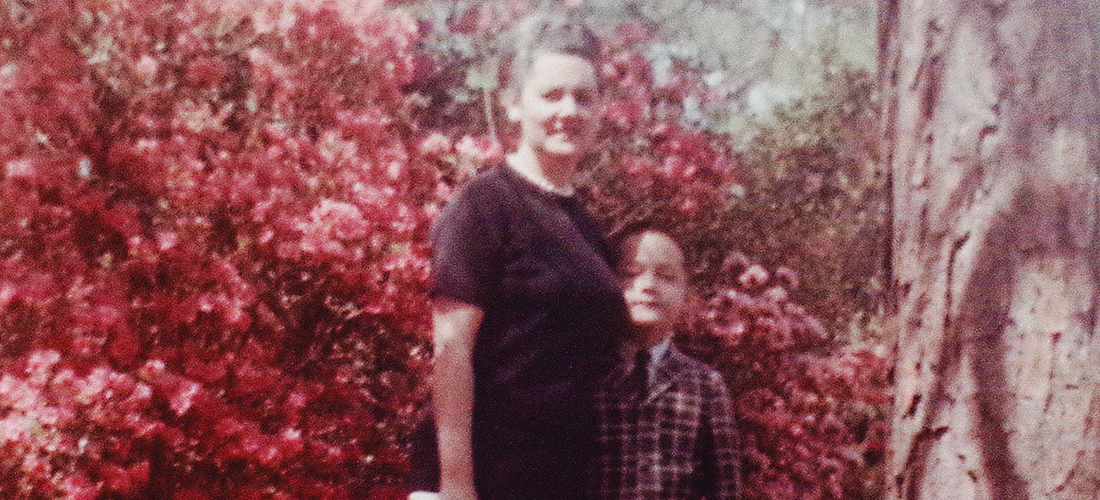

To my memory, still keen though he has been gone 40 years, Dad wasn’t big on sit-down discussions of serious matters. If, in the early 1970s, we had been wearing Fitbits instead of Timexes, they would have shown considerable steps taken during our “Facts of Life” conversation as we paced around the house one afternoon, each doing his best to speak of anything but the birds and the bees.

We got through that talk, fragmented though it might have been, despite our mutual reluctance. That was not the case when it came to my father’s military service, memories of which were as off limits to me as the bottle of Canadian Club stashed in the far reaches of a kitchen cabinet.

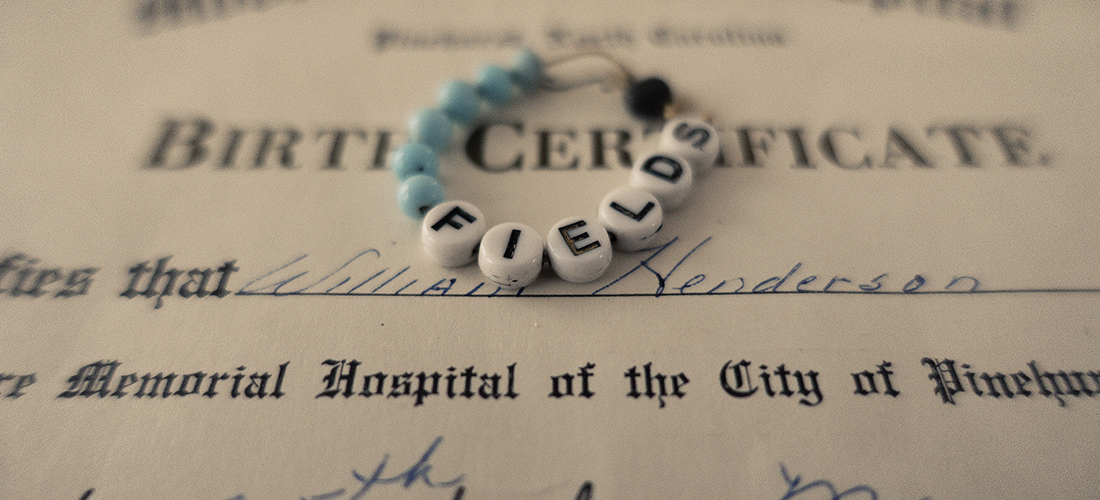

The hard stuff of war had come years earlier as my father, a corporal in the 161st Parachute Engineer Company, fought in the Pacific theater in 1944-45. Like so many others, William E. Fields had been plucked from an ordinary life — in his case, a long-haul truck driver transporting produce from his hometown of Jackson Springs to locales along the Eastern Seaboard — to do extraordinary things in the Allied war effort.

In 2020, the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, plenty of stories will be told about men and women who never wanted to talk about themselves or what they went through.

Dad was inducted Oct. 15, 1942, in Fort Bragg. By the spring of ’44, he had his wings, a wife and a will. My parents’ first child was due that November, by which time Dad was about 9,000 miles from home. An assistant unit foreman, second in command of a squad of parachute engineers, my father directed combat and demolitions work, and helped erect barriers and traps against the enemy.

His unit of airborne engineers was attached to the 503rd Parachute Regimental Combat Team. After fighting in the New Guinea and Luzon campaigns, Corregidor was next as the United States sought to reclaim the rocky island in Manila Bay overtaken by Japanese forces in 1942.

“The airborne landing was one of the most — if not the most — daring, unusual and successful in the history of airborne operations,” authors James and William Belote wrote in Corregidor: Saga of a Fortress, of the Feb. 16, 1945 operation involving 2,065 paratroopers descending from C-47s only 400 feet above a tiny landing zone on a windy morning. The first time I watched a Pathé newsreel film of the jump, the jeopardy of the troops became very real.

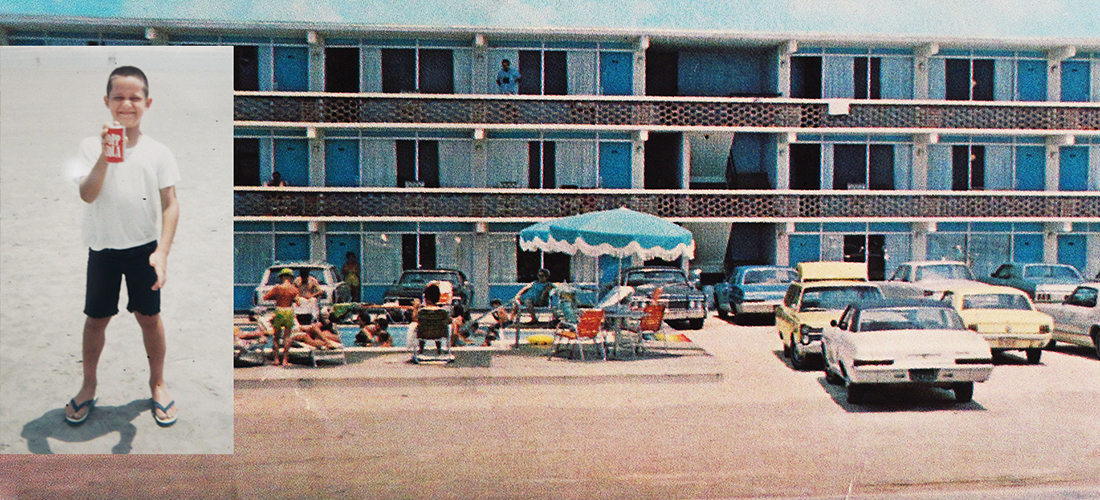

I’ve wondered if my mother, in North Carolina with her infant daughter, Dianne, read this Associated Press account published Feb. 18 in the Charlotte Observer and papers across the country: “Plane after plane dropped 10-man teams, some beyond the cliffs, some in rocky ravines but the majority on the ‘topside’ where they were to the rear of enemy guns pointing out to the China Sea. The ’chutists carried full equipment.”

Dad wasn’t in the majority and became one of hundreds of casualties when he landed on uneven terrain, shattering his right ankle. After a long recuperation, he would recover to walk without a limp but was plagued the rest of his life by tropical ulcer or “jungle rot” on the joint and varicose veins in his right calf.

As I found out just recently from an older cousin to whom Dad once confided a decade after the war, getting badly hurt was only part of his Corregidor story. Wounded and alone after being blown off course, he had to hide in a crater covered by his parachute to avoid being seen by Japanese troops before eventually being rescued and evacuated by comrades. It would be two months before he returned to the United States, and September until he was discharged from a convalescent hospital in Virginia with $144.14 and a Purple Heart that cost much more than that.

On Feb. 16, I will be thinking a lot about an ordinary man and the stories he wouldn’t share. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.