PINESTRAW'S 20TH ANNIVERSARY

Tag Archives: Feature

Pinestraw's 20th Anniversary

By Stephen E. Smith

Photographs by John Gessner

You can go almost anywhere, and there’ll be a (insert your favorite personal expletive here) with a guitar,” a curmudgeonly crony once told me.

I suspect he was talking about me. I’ve been toting around an acoustic guitar — in my car mostly — since I squandered $20 on a 6-string that beckoned to me from a pawnshop window when I was 14. The Kingston Trio strummed guitars, the girls swooned, and I had to have that Kay archtop with the bowed neck. No other instrument would do. (When was the last time you heard a testosterone-besotted teenager quip, “I just happen to have my tuba with me”?) At 17, I could flat pick the intro to The Animals’ “House of the Rising Sun” and bang out the first few chords of The Troggs’ “Wild Thing.” What more did I need to know?

If Americans have a national instrument, it’s the guitar, be it electric or acoustic or a combination of the two. According to Statista Research Department, 3.3 million guitars were sold last year in the United States. Any way you figure it, that’s a lot of exotic tonewood, bone, plastic, steel, glue, tortoiseshell and abalone. And that doesn’t account for the necessary accouterments — picks, strings, amps, mics, pedals, wires of every possible description, cases, straps, capos, gig bags, tuners, etc. Guitars constitute an in-your-face, above-ground market that flourishes on the internet via eBay and Reverb and lives in every city and settlement with a population of more than one. It’s a miracle that every kid in America isn’t busking on the curb.

In your lifetime, you’ll probably buy a guitar, or you know someone who will. With millions of options available, making an intelligent choice can be time-consuming and expensive — and ultimately disappointing. If you buy the wrong instrument — one that’s difficult to play and sounds crappy — the novice picker may become disillusioned and never fully realize the fulfillment music can bring into his or her life.

The guitar market is inundated with defective, cheap, and poorly constructed used instruments that are available for a pittance, while at the other extreme, you can make the investment of a lifetime if you stumble upon a one-of-a-kind gem. Kurt Cobain’s Martin 1959 D-18E acoustic recently sold for $6 million, and Bob Dylan’s 1964 Fender Stratocaster — the one that antagonized the crowd at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival — is a steal at a million bucks. Mark Twain’s 1835 2 1/2-17 Martin, which cost $10 new, is valued at over $15 million.

Used, worn-out instruments flood online auctions. Many of these are catalog guitars sold from 1920 through the mid-’60s. They have the virtue of being American-made, but they were ordered through Sears (Supertone/Silvertone), Montgomery Ward (Airline), or a myriad of more obscure distributors, and were often delivered in unplayable condition with a string height and tension that would suck blood straight out of your fingertips. Even if you lucked into a medium-grade and high-end used guitar, the truth is simple: Guitars wear out. The necks warp, the soundboards crack, the tuners fall apart, and the bridges pull up. They can be repaired, but the services of a capable luthier don’t come cheap, and you can spend more money restoring an old guitar than you will pay for a new, more playable model.

So where do you start the quest for that 6-string soulmate? If possible, borrow a guitar. Get a feel for the instrument. Learn a couple of chords. Sing a simple song. If you decide to purchase an instrument, don’t go online and click on the first thing that strikes your fancy. There’s no telling what will arrive in the mail. How a guitar looks on a computer screen and how it sounds and feels when you’re caressing the strings are very different things.

Or you might begin by watching Daniel Putkowski’s 2023 documentary Heirloom: Guitar, snippets of which were filmed in Southern Pines and feature Greensboro luthier Bob Rigaud. The doc is a simple primer for the unschooled. Putkowski begins with an ingenious admission: “I’ve been trying for 20 years to figure out what makes the guitar so popular in American music and across the world.”

Rigaud, who has crafted boutique instruments for Graham Nash, John Hiatt and David Crosby, believes the guitar is spiritual: “The guitar is probably the easiest instrument to play — of course it’s one of the hardest to master. . . It’s spiritual, and it speaks to people in their own lives — love, loss, all subjects.” The professionally produced documentary traces the acoustic guitar’s evolution from a parlor instrument into the most popular music-maker in the world. Segments are supplemented by clips of Bryan Sutton, David Grier, Florence Dore and others explicating their love of the instrument and include step-by-step visuals of a luthier building a custom boutique guitar from scratch. Heirloom: Guitar is available on YouTube and is a good introduction for anyone who is considering a purchase.

We’re fortunate to live at a propitious moment in the evolution of the guitar. CNC (computer numerical control) machines improved construction and playability, and if the guitar is made by a reputable American company — Martin, Gibson, Collings, Taylor, etc. — it’s likely to be a superior instrument. And there are hundreds of American luthiers — too many to mention here — who build custom guitars of the highest quality, although these models are likely to be pricy.

Among imported guitars (“offshore” is the popular euphemism) constructed in China, Indonesia, Japan, etc., deals are to be had. American players generally look down on these foreign models, but the Chinese have been producing acceptable instruments for the last 30 years, and Japan’s Takamine, Alvarez and Yamaha are welcome on any stage or in any song circle. After all, musicians in the Orient were playing stringed instruments long before the Vikings set foot in Vinland. It’s all right to be a guitar snob, but it’s unnecessary — and unbecoming.

Online guitar retailers abound. Musicians Friend, Cream City Music, Sweetwater, Chicago Music Exchange and other music companies will allow you to purchase an instrument and return it in new condition for a full refund if you don’t like what you hear. But the best and easiest place to start your search is your local music store. (There are chain guitar stores you can frequent if you can endure the bone-jarring racket of 10 customers playing White Stripes’ “The Hardest Button to Button” with their amps maxed out.) But a quiet, comfortable atmosphere where you can handle the instrument and hear what’s played beneath your hands is the way to go. A guitar must feel right as well as sound right.

Southern Pines has had its share of cliquish musical haunts. The Pinedene Jazz Center, which was featured on WRAL’s Tarheel Traveler many years ago, comes immediately to mind. The hole-in-the-wall establishment on U.S. 1 South flourished as a gas station selling Black Diamond Strings until it morphed into a music store that eventually succumbed to changing times and a shift in ownership.

The more substantial Casino Guitars (www.casinoguitars.com), which now anchors, along with The Country Bookshop and The Ice Cream Parlor, downtown Southern Pines, carries an impressive array of guitars, many of them high-end instruments that proprietor Baxter Clement ships worldwide. Casino has grown into one of the premier guitar stores in the Southeast. The service is excellent; the crew is knowledgeable. Clement, a music graduate from Vanderbilt University, thoroughly knows his stuff, and he truly loves guitars. He has a solid business plan. He knows that customers in the market for a guitar need to feel and hear the instrument. They need to hold it in their hands and sense that sudden bond: Ah, yes, this is the one!

“When a customer comes in the front door, we try to make them feel at ease,” Clement says. “They can take their time and browse and find an instrument they feel a connection to. Our job is to help the customer find a guitar that speaks to them.”

As for the price range of his stock, he’s philosophical. “Every guitar gets you to the same place, like a car moving from A to B,” he says. “A quality guitar will just get you there faster. And, too, customers should keep in mind that many of the cheaper guitars are produced by workers who aren’t paid a fair wage. In some cases, they’re built by prison labor who work in unsafe conditions without masks or eye protection.”

How much should you pay for a new or used guitar? Is there a decisive difference between a high-end and a cheapo-cheapo model? Nothing is absolute. If you do your research, listen to a trusted expert and, as Aristotle reminds us, trust your eyes and ears — “The Eyes are the organs of temptation, and the Ears are the organs of instruction” — you have a very good chance of purchasing a quality, playable instrument that will bring you years of satisfaction.

To determine how low-end guitars have improved in recent years, I ordered the cheapest playable new guitar I could find online. Recording King is a brand name conjured up by Gibson during the Great Depression. The guitars produced under the label were more lightly constructed and cost less than the typical Gibson. The Recording King moniker was eventually sold to a Chinese outfit that produces models at varying prices and quality. For $100, I purchased a Recording King from the “Dirty-30s” series, which boasts surprisingly impressive specs — a spruce top, nickel tuning machines, Whitewood (whatever that is) back and sides, mahogany neck, bone saddle and nut — all good stuff.

I toted the Recording King and my 2012 Signature John Sebastian Martin D Slope Shoulder, which boasts the specs of the very best of American guitars (there’s one for sale online for $15,500), to a gathering of the Weymouth Song Circle, which meets on the last Tuesday of every month, to allow the experts to weigh value and quality. And they did.

The Recording King sounds, well, good enough. It is surprisingly playable out of the box. It’s bright and responsive and holds its own with other guitars when fingerpicked or strummed. Except for minor finishing details (the fret ends are like septic spikes), the Recording King would have held its own in the 1950s and ’60s folk era.

But when we played the Martin DSS, trained ears held sway. The Martin was by far the more desirable guitar. Everyone wanted to pick a few tunes on the DSS while the Recording King sat slumped, neglected, in the corner. It’s a viable guitar, fun to play when accompanying others, but the superior Martin demanded the attention of experienced pickers. Which begs the question: Is one Martin guitar worth 155 Recording Kings? Whatever the answer, this much is certain: The serious player should experience long-term satisfaction with his or her purchase. You don’t want to outgrow your new guitar in the first month of ownership or be discouraged by its inadequacies.

Everyone should have a little music in his or her life, if only to escape the electronic morass we’re forced to inhabit. When you hold an acoustic guitar in your hands, it’s just you and the instrument. For better or worse, it reflects what you feel and believe — and who you are. It also connects with others, and there’s a strong sense of community among guitar players, whatever their skill level. And Lord knows, genuine connection is what we need more than ever.

Even casual music lovers appreciate the sense of camaraderie that guitars convey. I recall a summer afternoon 40 years ago when I was driving into Austin, Texas, to visit my singer-songwriter brother. I had my radio tuned to a local station that was broadcasting live coverage of a gathering of 500 guitarists on the grounds of the State Capitol. At precisely high noon, they all played “Wild Thing” — raucous head-pounding A, D, E, D, A, D, E chords blasting through the transistors in perfect generational unison.

Oh, how I longed to be among them!

By Deborah Salomon

Photographs by John Gessner

Architectural styles can take a while to develop a following. Like bouillabaisse and paella, their ingredients are myriad, complex. They can age like fine wine.

Apply these guidelines to mid-century modern, made popular by a coterie of forward-thinking architects — some associated with N.C. State, others espousing Japanese concepts — who left their mark on central and eastern North Carolina beginning roughly in the 1950s.

Then, for a stunning rendering, stroll through the mid-century modernesque home of Richard and Molly Rohde on the Southern Pines Garden Club’s Home & Garden Tour on Saturday, April 5. Notice the ways, some subtle, that the Rohde residence differs from neighbors at the Country Club of North Carolina — a pebbled area at the entrance; jumbo glass wall inserts; five strategically placed mini-gardens, one walled and sunken; and a wraparound Juliet balcony. All are born of Richard’s landscape design prowess, as is the giant golf ball atop a stump pedestal at the front walkway that was carved from a tree that grew on that very spot.

The house was built in 1980. The Rohdes have lived there for 10 years. “We are a blended family,” Molly explains, totaling seven children and 13 grandchildren. They keep a townhouse in Raleigh and a house at Topsail Beach, where the gang gathers May to October. Molly calls it their “happy place.”

Richard grew up in a stucco in Miami before moving to Winston-Salem; Molly in an interesting mountaintop residence in New York State. While living in Raleigh Richard enjoyed golf excursions to Pinehurst enough to suggest a grown-up retreat that he could combine with his office.

“The architecture, the sightings, the dogwood and azaleas in bloom — we decided on the spot and made an offer,” they recall. Another appeal: The house was designed by Hayes-Howell and Associates, the pre-eminent modernist architects of the era, who left significant marks on Moore County.

Richard planned whatever adjustments and additions that were required. The walk-out basement “playroom” with “wet bar” (in previous parlance) became his office. His desk was formerly a trestle table. He added a terrace with a firepit and an extended Juliet balcony ending in a metal circular staircase. Beyond, artistically arranged boulders define gardens where a sea of daffodils bloomed in late February.

The diversity of landscaping makes the pie-shaped 1-acre lot sloping toward the lake appear larger. Although the house layout is longitudinal with two wings — totaling 3,250 square feet — nothing suggests a single-story 1950s ranch. Enter the front door, step into a foyer flooded with light, and gasp at the dining room, directly opposite, with line-of-sight to the lake. Black and soft milky white dominate here. The black lacquer sideboard, which came with the house, is covered in Asian motif carvings. The table with a thick plate glass top, also a holdover, picks up sunbeams. Petals on a low-hanging light fixture suggest a lotus flower. Framed architectural renderings of the house, a testament to its provenance, hang on a side wall. Wallpaper adds texture in neutral, solid colors, no patterns.

Off to the right is the living room with an 18-foot ceiling, white carpet, white upholstery, a high triangular window, and a plate glass coffee table. In a corner surrounded by windows and glass doors stands a round glass-topped table where Molly and Richard take meals. Near the fireplace hangs an exquisitely embroidered framed kimono, once part of Molly’s wardrobe.

So far, elegant, very adult, perfect for entertaining.

The kitchen rates a giggle from Molly. Judged against today’s extravaganzas, it is modest yet stylish with black and white floor and tile backsplash, simple cupboards and pulls designed by the original architects, perfectly adequate for preparing meals for two, Molly notes.

The bedroom wing stretches off the foyer, the length of its hallway emphasized by a seemingly endless row of Chinese screen panels. Where they end the master suite opens into a large sitting room, doubling as Molly’s office, with built-in bookcases, TV, sofa and door onto the balcony. The highlight in her bathroom is a sunken Jacuzzi whirlpool tub in a deep red enamel, inspiring Molly to paint a fanciful hall tree for hanging towels. Richard’s bathroom: sedate black tiles.

Molly continued the Asian theme in jewel-toned fabrics and figurine lamp bases, some from her daughter’s boutique, Union Camp Collective, in Raleigh. She also framed a child’s kimono, worn by her daughter.

Molly and Richard, both longtime collectors, have curated and combined their possessions in the master suite and two guest bedrooms, one with a second set of built-ins filled with books. The result: a blended family, combined furnishings, historic Carolina architecture, a whiff of the exotic, and a home office overlooking the golf course. Richard recalls his first impression of life at CCNC: “I came through the gates and thought, whew, this is relaxing, another world.”

Lucky Richard. Fortunate Molly. In semi-retirement they found Zen.

By Ross Howell Jr. • Photographs By Amy Freeman

Have you ever seen this?” asks Bari Helms. “I found it in some boxes.”

Helms is the director of the archives and library at Reynolda House Museum of American Art, the storied estate that is now part of Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem. She slides the rendering toward Phil Archer, the deputy director at Reynolda, the family mansion that houses a permanent collection of three centuries of American art and sculpture.

Archer shakes his head, touching a finger to the edge of the drawing.

“I don’t think so. Not with those perpendicular wings. A little too Versailles for Katharine, isn’t it?” Archer asks. He and Helms exchange knowing smiles.

Helms produces a letter from that same “Katharine” to Lord and Burnham, the premier builder of glasshouses in America during the mid-19th and early 20th century, dated May 27, 1912. In it, she details what she wants her estate’s conservatory to include — a palm room, a “good-sized” grapery, a tomato section, a large vegetable section, a propagating room and a “nice workroom.”

When Lord and Burnham responded with their plans and perspectives, and their quote for $7,147, Katharine wrote back that it was too much money. The greenhouse additions in the rendering were removed.

“In all her correspondence, you get a sense of how direct, hands-on and detail-oriented Katharine was,” Helms says.

In December 1912, Katharine wrote another letter to Lord and Burnham, complaining that the workers they’d promised had not yet arrived on-site. In January 1913, she wrote again, noting that parts of the conservatory were not being built to her specifications.

“Katharine was very polite about it,” Helms says, “but insisted that she was making Lord and Burnham aware of the issue so they would fix it.”

No doubt they did.

Katharine was, of course, Katharine Reynolds, the irresistible force behind Reynolda, completed in 1917. Backed by the tobacco empire of her husband, R.J., Katharine began to purchase tracts of land near Winston-Salem, eventually acquiring more than 1,000 acres, each parcel deeded in her name alone. Her idea was a Progressive one — to create a self-sufficient estate that included a country house, a farm utilizing the latest in technology and agricultural practices, a dairy, recreational facilities and a school.

The conservatory — located very near what is now Reynolda Village — was an integral part of Katharine’s design. October 2024 marked the end of its restoration, a yearlong project made possible by a gift from longtime Reynolda supporters Malcolm and Patricia Brown.

Born in Mount Airy in 1880, Katharine Smith Reynolds was a daughter of America’s Gilded Age and a wife in the Progressive Era of the industrialized New South. In the period photographs at Reynolda, she’s the young woman in the gorgeous outfits who doesn’t seem to be looking at the camera, but, rather, directly into your soul. To this day, her spirit and determination inform every aspect of Reynolda.

Leaving her home in Mount Airy in 1897 to attend the State Normal and Industrial School — now UNCG — she later withdrew because of a typhoid epidemic and finished her studies at Sullins College in Bristol, Virginia. In 1902, Katharine joined the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company in Winston-Salem, where she served as personal secretary to the owner, R.J., a distant cousin who was 30 years her senior. In 1905, Katharine and R.J. married.

Between 1906 and 1911, Katharine gave birth to four children — at grave personal risk, according to her physicians, since she had been plagued with heart problems that started in childhood. By all accounts, the Reynolds marriage was a happy one, and R.J. was confident in his young wife’s abilities, often consulting her on business matters.

“Katherine wanted the estate to look and feel like an old English hamlet,” Archer says. “Burying utilities was high-tech for Katharine’s time, but that’s what she wanted.”

The conservatory restoration project, which would become the Brown Family Conservatory and Reynolda Welcome Center, was led by Jon Roethling, the director of Reynolda’s gardens. The work was done by Cincinnati-based Rough Brothers (pronounced rauh), a subsidiary of Prospiant.

“Rough Brothers had access to actual Lord and Burnham plans and molds,” Roethling says. So, for the Reynolda restoration, the company could use templates on hand, extruding aluminum pieces to match the originals.

The tinted glass needed for the restoration was made by another company. It’s so specialized, the company only manufactures it twice a year, delaying completion by months. The wait was worth it, however, since the unsightly aluminum shutters added to the palm house and greenhouses in a previous renovation could be removed. Moreover, the manufacturer had the equipment to produce curved glass. This meant that the elegant shape of the original architecture — supplanted by the use of flat glass panes in a previous renovation — could be restored.

“When I walk into the palm house now, the architecture just sings,” Roethling says.

There were the additional challenges of heating and ventilation — critical to a conservatory. “We stayed with the original concept of radiant heat,” Roethling explains, “though the new system is very sophisticated.”

Ventilation was a trickier issue, since the conservatory is vented throughout — foundations, walls and roof. From the time the conservatory was built until this restoration, these many vents had to be cranked open or shut by hand.

“You have to strike this balance of having architecture that reflects 1913, but also having the convenience and efficiency of systems that are modern day,” Roethling says. “Knowing Katharine, one of the most progressive women of her time, I was sure there was no way she would want us to be hand-cranking vents in this day and age, so we made the jump to automated.”

The new system automatically responds to wind flow, wind speed and precipitation, adjusting ventilation as needed. Changes can also be made remotely, using Wi-Fi. Once, when Roethling noticed a thunderstorm developing, he went to the conservatory to see how the new system would respond.

“As the wind rose and the storm started rolling through, I watched the vents immediately close a bit,” he says. “When the wind grew stronger, the vents shut completely, protecting the greenhouses.”

End-to-end, the central structure of the conservatory and the greenhouses flanking it extends more than 300 feet. Sod has been laid the entire length, creating a walking path for visitors. Between the edge of the sod and the foundations of the greenhouses are planting beds, about 8 feet wide, filled with peonies.

“The problem,” says Roethling, “is once the peonies bloomed out, that was pretty much it, visually. I needed someone who could do something amazing.”

Roethling reached out to Jenks Farmer, a plantsman in Columbia, S.C., who served as director of Riverbanks Botanical Garden in West Columbia and was the founding horticulturist of Moore Farms Botanical Gardens in Lake City. Farmer created a design for the peony beds incorporating other perennials that provide visual interest throughout the growing season.

“Jenks is great,” Roethling says. “He loves balancing history with what’s relevant today.”

In the conservatory proper, each bay has a different theme. “This first bay is in the spirit of an orangerie, which represents the birth of greenhouses,” says Roethling. Much like the original 17th-century orangeries in England and throughout Europe, the bay also features olive trees and other fruiting plants, and will be used to illustrate a narrative history of the development of greenhouse structures over the centuries.

The next bay is an arid greenhouse, featuring the five Mediterranean climates of the world — Southern California, the Mediterranean Basin, South Australia, South Africa’s Cape area and central Chile.“This is a fun thing to educate kids,” Roethling says. “To explore with them how the plant palette changes, how the plants adapt.”

The central palm house is elegant in its features with sealing wax palms with their deep red canes, and tall Bismarck palms with their silver fronds, all in large containers. Visitors can compare the broad texture of a palm frond to, say, the fine texture of a fern. “There’s a lot of texture — greens, whites and silvers,” Roethling says.

The next greenhouse bay features bromeliads, orchids and other flora that thrive in the tropics. It’s all about color — abundant, dramatic color. “In here, I want to have freaky things that visitors walk up to and ask, ‘What is that?’” says Roethling with a broad smile.

The final bay serves as a holding house for resting orchids, organized by types, with interpretative signage.“Even though the orchids won’t be in bloom there,” Roethling says, “that greenhouse will still be beautiful and educational.”

Just as Katharine would have expected.

by Jim Moriarty

Herman Wouk, the author of both the novel The Caine Mutiny and the play The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, took great pains to let his audience know that nothing that happened aboard the fictional ship the USS Caine occurred in the very real campaigns he experienced during his World War II service in the Pacific Theater. A note to the play says, “The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial is purely imaginary. No ship named U.S.S. Caine ever existed. The records show no instance of a U.S. Navy captain relieved at sea under Articles 184-186. The fictitious figure of the deposed captain was derived from a study of psychoneurotic case histories, and is not a portrait of a real military person or a type; this statement is made because of the existing tendency to seek lampoons of living people in imaginary stories. The author served under two captains of the regular Navy aboard destroyer-minesweepers, both of whom were decorated for valor.”

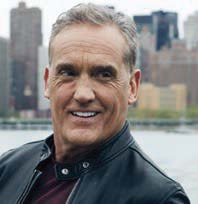

The Judson Theatre Company will bring Wouk’s courtroom drama, informed by his service aboard the USS Zane and USS Southard, to life in five performances starring John Wesley Shipp and David A. Gregory, beginning Thursday, April 24, and running through Sunday, April 27, in BPAC’s Owens Auditorium, 3395 Airport Road, Pinehurst. The novel, published in 1951 in a wave of post-war literature that included books like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, earned Wouk a Pulitzer Prize. The play debuted on Broadway in January 1954, directed by Charles Laughton. That June the movie The Caine Mutiny was released, gaining seven Oscar nominations, including one for best actor for Humphrey Bogart’s riveting performance as Lt. Com. Philip Francis Queeg.

The play is performed in two acts, organized simply with the first act as the prosecution and the second the defense. “If you think about the film and even the book, they both literalize what happened on the ship,” says Judson Theatre’s executive producer, Morgan Sills. “With the play, the audience gets to piece together what happened on the ship from what they glean from all the different testimony they hear. In the end, the audience has a job to do, to decide what they believe is the real story. And that’s theatrically interesting. It can change from night to night the way that live performances change from night to night and books and films do not.”

Shipp, who returns to Judson Theatre after playing the role Juror No. 8 in its 2016 production of 12 Angry Men — Henry Fonda’s part in the 1957 movie — takes the part of Queeg, the ship’s commander relieved of duty during a vicious storm by Lt. Stephen Maryk. He’s played by Jacob Pressley, whose Judson summer theater festival credits include Gutenberg! The Musical, The Last Five Years and They’re Playing Our Song. Maryk’s defense counsel is Lt. Barney Greenwald, played by Gregory. Coincidentally, Fonda played Greenwald in the original Broadway production.

Though tasked with defending Maryk, Greenwald has no particular fondness for his client. On the other hand, he knows that in order to perform his sworn duty to zealously represent him, he will have to cross-examine Queeg in the most brutal manner, a prospect that gives Greenwald no pleasure. At its dramatic height Greenwald and Queeg go head-to-head. And it’s there that Judson’s production of The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial benefits from the long working relationship between Shipp and Gregory.

In his role as Eddie Ford on One Life to Live, Shipp — whose credits and awards (including two Emmys) over a 38-year acting career are too numerous to mention — was frequently at loggerheads with Gregory, who played his son, Robert, on the daytime drama. “I was the abusive father and he was my oldest son, Bobby Ford,” says Shipp. “I had three sons and I treated them all differently. Bobby was the one who would push back. We had a great time. It’s just one more reason I’m so excited to get on stage going head-to-head with this man because I know how talented he is, how resourceful he is. The thing I love about David is he brings his A game all the time. I feel like we challenged each other.”

Moving at the speed of a soap opera, between scenes Shipp and Gregory would occasionally swap their character’s lines if they thought it deepened the connection. “We have a shorthand with each other, working 15-16 years ago on the soap where we would have to clash,” says Gregory. “We know what that territory is, but we haven’t experienced it with this play and these words.”

One Life to Live isn’t their only collaboration. Gregory wrote a scripted podcast, Powder Burns, about a blind sheriff in the Old West. It premiered on Apple Podcasts in 2015 with Shipp in the role of the sheriff. Critically acclaimed, it earned Gregory a Voice Arts Award in 2017. They’ve also worked together on a two-person play Gregory wrote about Jimmy Stewart and Henry Fonda called Hank & Jim Build a Plane, which Shipp and Gregory performed in a workshop in New Orleans in 2018, the last time they appeared on stage together. As opposed to their One Life to Live personas, Hank & Jim is about two men, famous for their shared model airplane hobby, who are at odds with one another over pretty much everything else — including a woman — and who won’t, or can’t, challenge one another. In something of a metaphor for our time, it’s about what Hank and Jim, sharing the same tiny garage space, can’t say to one another. “It may have been Jimmy Stewart’s daughter who said the interesting thing you’ve done is that you’ve taken two men of very few words and written what they would have said to each other if they could have,” says Shipp.

Finding the right words won’t be the problem in The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial. “Plays like this get done so often because they’re very, very good,” says Gregory. “The author has meticulously made this as perfect as possible. We just get to add on top of that. It’s a blast.”

Shipp sees only one real drawback: “My only complaint is that it’s too short.”

By Jason Oliver Nixon and John Loecke • Photograph by Bert VanderVeen

There’s truly an art to hosting guests. To making a visitor feel supremely welcome without having to kowtow to their every whim and whimsy.

John and I love entertaining in all its forms, and we really raise our game when it comes to hosting houseguests at our High Point home, the House of Bedlam. Think The Ritz Paris by way of North Carolina, but cozier, softer, and a lot more fun. Dining room disco, anyone? We just had an international guest arrive from London, and we wanted her stay to be as comfortable and memorable as we could make it. Quite simply, we want every one of our houseguests to feel like they’re at home and leave them wanting for nothing. A good mattress and a clean room are a given, but we are all about the small touches, the personal ones that focus on our guests’ comfort.

That said, we are very clear about our “deliverables.” This isn’t a restaurant. We aren’t the maids. Yes, please strip the bed when you depart. We will have coffee and English muffins ready every morning; we don’t make eggs. And a gift or dinner out on the town is always welcome.

Here are a few tried-and-true recipes for the ultimate guest bedroom from your friends at Madcap Cottage . . .

— We love to put flowers next to the bed. Flowers truly make the room feel fresh, alive and cared for. You know your guests well, so think about their favorite blooms and adorn the nightstand with that particular blossom. At this time of year, what is more cheerful than a simple vase abundant with daffodils? A great stack of books is always welcome, too.

— Place either a bottle of water next to the bed or fill a glass decanter with water and accompany it with a lovely crystal glass.

— Email a week before to ask your guests’ must-haves or food preferences. Oat milk, almond milk, gluten-free bread? The Madcaps have you covered. Our recent guest wasn’t fussy but she is a chocoholic. We had some of our Hammond’s chocolate bars on standby for her, so she could try some Southern sweet treats.

— Add lovely toiletries pillaged from a hotel to your guest bathroom. Save the Hermès for really good friends or treat them to some of your favorite toiletry brands. We love to leave our guests with some of our French lavender bath bombs from the Old Whaling Company to help them relax and unwind during their stay.

— Have a plug-in outlet with USB port easily visible and plugged in near the bed. When they’ve retired for the evening after a long journey, the last thing a guest needs is to be crawling around on the floor trying to find an accessible plug.

— Good towels, well fluffed. The bigger and bouncier, the better.

— Extra toilet paper in a basket atop the toilet. Be kind and save your guests the indignity of having to request more TP.

— A soft rug next to the bed. We have small accent rugs next to every bed in our house. Besides the fact that they make the room cozier and look more layered, they make getting out of bed that much easier when you’ve got a soft landing to look forward to.

So there you have it. That’s how we host a house guest, the Madcap way.

Enjoy!

By Chrissie Walsh Doubleday and Tara Walsh York

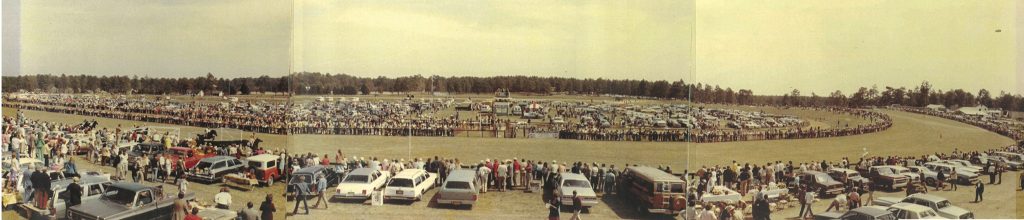

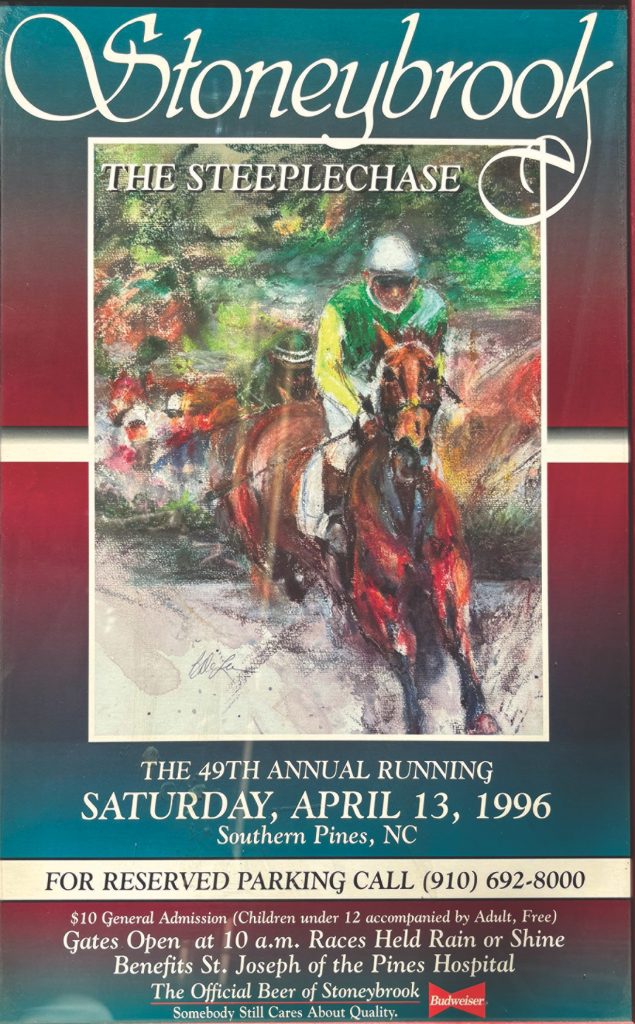

Elevated to one-word status, the locals simply called it Stoneybrook. But it was much bigger than just a day at the races.

The Stoneybrook Steeplechase was an outdoor cocktail party rivaling the grandest in the Southeast, and once you went, you never wanted to miss it again. Whether folks donned fancy hats and dined at banquet tables adorned with fine linens and chilled Champagne, sat on the back of a pickup truck with a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken and a cooler of beer, or spread a blanket on the grass with a picnic basket, it was the place to be. More than just a lively celebration, though, Stoneybrook embodied the thrill of horse racing.

The perfect parking spot was as coveted as a family heirloom. People arrived on foot or by bus, in cars or by limo, but regardless of how they got there or where they came from, when they heard the announcer say “The flag is up!” they raced to the rails to watch. At its peak, nearly 40,000 spectators packed into Mickey Walsh’s Stoneybrook Farm, transforming it into a carnival of energy and tradition. It was the first sunburn of spring, and the ultimate mingling of community and family.

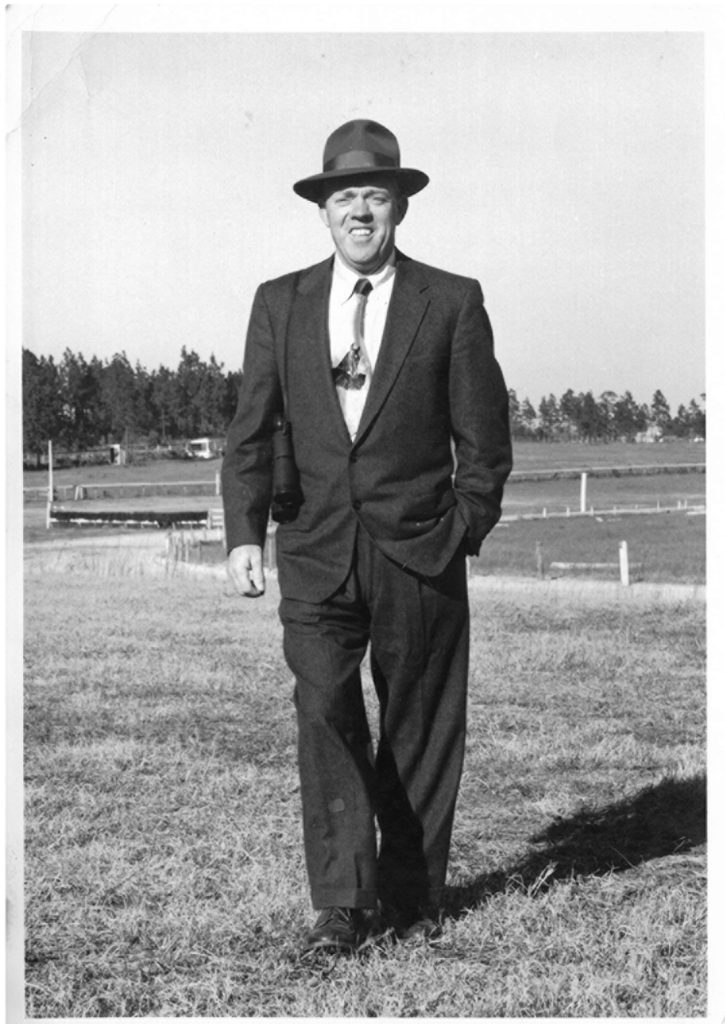

On St. Patrick’s Day 1947 Michael G. “Mickey” Walsh, an Irishman from Kildorrery, County Cork, Ireland, brought his dream of starting a steeplechase race to life on his 150-acre farm in Southern Pines. That year, the first Stoneybrook Steeplechase set the stage for nearly half a century of camaraderie, equestrian excellence and cherished memories — not just for the thousands who attended, but especially for Mickey’s own family.

After immigrating to the United States in 1925, Walsh gained fame in the show jumping world, where his horse, Little Squire, achieved a remarkable three consecutive wins at Madison Square Garden. With ambitions that stretched beyond show horses Walsh settled in Southern Pines in 1944 with his wife, Kitty, and transitioned to steeplechase racing, where he became the nation’s leading trainer from 1950 to 1955. The Stoneybrook Steeplechase would become part of the National Steeplechase and Hunt Association in 1953 and one of the premier horse races in the Southeast.

The success of Stoneybrook relied heavily on the community. The Knights of Columbus organized the parking logistics and directed the influx of visitors on race day, and in the spirit of community that defined Stoneybrook, profits from the event were donated to St. Joseph of the Pines, a nursing home. Within the Walsh family, the event was a labor of love. Marion Walsh, Mickey’s daughter-in-law, managed the Stoneybrook office for many years before the responsibility fell to Phoebe Walsh Robertson, Mickey’s youngest daughter. From selling parking spots to securing sponsorships or working with the horses, all the Walsh women played a vital role in sustaining the tradition.

For the Walshes, Stoneybrook was far more than a public event — it was a cornerstone of their lives. The farm was a haven for Mickey’s children and grandchildren, who spent their days riding horses, playing in hay barns and absorbing the rhythms of farm life. Duties like mucking stalls and riding racehorses before school cultivated a deep appreciation for hard work and horsemanship.

Mickey’s daughters Cathleen, Joanie, Audrey and Maureen were accomplished riders, and raced a time or two. Later, his grandson, Michael G. Walsh III, followed in their footsteps, becoming a leading amateur jockey. In one poignant moment Mickey watched his grandson race at Stoneybrook, riding every jump in spirit alongside him. When young Michael crossed the finish line in first place, Mickey’s pride was unmistakable, his joy radiating through his smiling Irish eyes. His siblings and cousins shared in the pride, racing to the winner’s circle to surround him for the winning photo.

Stoneybrook weekend was a cherished reunion for the entire family. With seven children and 29 grandchildren, the gathering brought relatives from across the country, including Oklahoma, Boston and New York. Close friends, like the Entenmann family — famous for their baked goods — also attended every year, adding sweetness to the occasion.

The festivities extended beyond race day, beginning with the Stoneybrook Ball on Friday night. On race morning, Grandmom Kitty hosted her renowned Owners, Trainers and Riders Brunch, preparing all the dishes herself. Following the races, the celebration continued with an evening reception for horse owners, trainers and jockeys, featuring music, food and drinks. Sunday brought the weekend to a close with a lively bocce ball tournament hosted by Mickey’s son, Michael G. Walsh Jr.

As each Walsh family member reached adulthood, they embraced the full spectrum of Stoneybrook’s traditions, bringing their friends to share in the magic. The event became a rite of passage, a chance to create lifelong memories and forge lasting connections. Even as the races drew thousands, the essence of Stoneybrook remained intimate for the Walsh family. It was a tapestry of laughter, camaraderie and shared experiences. This sense of togetherness extended to the broader community, where old friendships were rekindled and new ones blossomed.

Mickey Walsh’s passing, in 1993, marked the end of an era. The races at Stoneybrook Farm eventually ceased in 1996, but their impact lingered in the hearts of all who had been part of them, spectator and family alike.

For the Walshes, the memories of those weekends — the excitement of the races, the joy of reunion, the shared pride in their heritage — remained indelible. Though the races ended just shy of 30 years ago, the memories endure, a lasting tribute to Mickey Walsh and the indomitable spirit he embodied.

Story and Photographs by Todd Pusser

Spending the better part of the morning cleaning up limbs and pinecones left over from the previous night’s storm, I slowly make my way around our suburban yard. Ominous clouds finally give way to bright blue sky and a blazing August sun. Near the brick steps leading up to the front door, I pause. At the top of a waist-high spicebush, a single curled leaf, nestled among a bouquet of more “normal-looking” straight leaves, catches my eye. My pulse quickens.

Over the past few years, I have made a concerted effort to replace the ornamental shrubs and non-native flowers that line our walkway with more wildlife-friendly native plants. It’s been a slow process, but the obvious increase in pollinators in the yard, in the form of bees, moths and butterflies, has shown that the work is starting to pay dividends.

A small shrub native to eastern North America, spicebush produces abundant red berries throughout summer and fall that the local birds love. Named for its aromatic leaves, which smell like citrus and allspice, spicebush also attracts the attention of one very special butterfly, the aptly named spicebush swallowtail. These black, palm-sized butterflies lay their eggs on the shrub’s fragrant leaves. Upon hatching, the caterpillar larvae munch the spicebush leaves (their primary food resource) with gusto, much in the same way I tear into a bag of barbecue potato chips.

I have monitored the spicebush every day since I planted it two years ago. Noticing the curled leaf, a telltale sign of an enclosed caterpillar, it looks like I have finally lured in a customer.

Like a kid on Christmas morning, eager with anticipation, I bend over and slowly unfurl the edges of the leaf, revealing a half-inch-long caterpillar. Immediately, two large yellow eyespots on its head grab my attention. Despite knowing what to expect, it is still a bit startling. Imagine how a hungry bird, like a cardinal, might respond.

You see, this special caterpillar is a snake mimic, and a darn good one at that. Its false eyes come complete with large black pupils. There is even a tiny white spot, a “catchlight” in each, which only adds to the illusion. Throughout the day, the caterpillar remains in its shelter, with the edges of the leaf pulled around its body, always with its head pointed up toward the tip of the leaf. That way, if a foraging bird were to encounter it, the first thing it would see would be the “face” of the snake.

For most of my life, I have been battling the misconception that one has to travel to far off tropical islands and jungles to find wild wonders. As a child, fed on a steady diet of television shows like The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau and Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, I could not wait to escape the confines of little ol’ Eagle Springs and explore the world. Now in my 50s and burdened by the usual hurriedness and complexities of adult life, I have to constantly remind myself that there are marvels to be found close to home. Discovering something like a caterpillar that mimics a snake right outside the front door never fails to illicit that childlike wonder of a world filled with infinite possibilities.

The drama between life and death plays out every second of every day across every nook and cranny of the wild. It’s an eat-or-be-eaten world out there. To gain a level of advantage, countless organisms utilize deception in their never-ending bid to stay alive. Camouflage and mimicry are the templates for survival. Optical illusions abound.

Take caterpillars, for instance. As they grow, all species shed their skins many times before pupating into a butterfly or moth. Biologists refer to each of these skin-shedding molts as instars. Caterpillars are packed with protein and many animals love to eat them, especially birds. One study found that a single clutch of young chickadees can consume up to 6,000 caterpillars before they fledge.

To avoid becoming a meal, caterpillars resort to all manner of trickery throughout different stages of their life cycles. Many resemble tree bark; others, twigs. Some look like lichen. A few possess vicious-looking armaments to deter would-be predators. A hickory horned devil, the largest caterpillar in North America, sports a pair of huge horns on its head. When disturbed, the devil thrashes its head violently from side to side, slamming its horns into its aggressor. Though intimidating, the hot dog-sized caterpillar is completely harmless. The snake-mimicking spicebush swallowtail caterpillar, mentioned earlier, is an even more surprising trickster in an early instar form, when its mottled black and white coloration resembles an unappetizing splatter of bird poop.

All caterpillars eventually metamorphose into butterflies and moths. And like their pupa, these winged wonders are relentlessly pursued by predators. As such, many of our native butterflies and moths rely on camouflage and mimicry to avoid becoming an easy meal.

Last summer, while walking along the edge of my parents’ Eagle Spring’s yard, I paused to look at a wasp perched atop a grapevine leaf. Underappreciated and loathed animals, such as wasps, hold a special place in my heart, and I cautiously stepped closer to examine the brightly colored insect in more detail. I realized something was a little off. For one thing, it had clear wings. Most wasp wings are opaque or dark. It also had a pair of bushy antennae and a wide waist — very unwasplike. Finally, I noticed that hairy tufts extended out from the tip of its abdomen instead of a stinger. It suddenly dawned on me. I was not looking at a paper wasp at all, but rather a day-flying moth known as a graperoot borer. Its disguise was on point.

Many insects, especially flies, beetles and moths, mimic stinging bees and wasps. Defenseless organisms that mimic dangerous ones employ an evolutionary survival strategy that biologists refer to as Batesian mimicry. Named for the Victorian naturalist Henry Walter Bates, who first described the phenomena in the humid jungles of the Amazon, this form of mimicry is surprisingly common and is not limited to insects.

Here in the Sandhills of North Carolina, the secretive and beautiful scarlet kingsnake is a dead ringer (pun fully intended) for the venomous coral snake. Both snakes possess alternating colorful bands of red, yellow/white and black and can be hard to tell apart. I still recall a little rhyme taught by Larry Dull, my sixth-grade science teacher at West End Elementary, to help distinguish between the two. “If red touches black, that’s a friend of Jack’s. If red touches yellow, it will kill a fellow.”

Several years back, while walking along the edge of Drowning Creek on my great-grandfather’s farm, I almost had a heart attack. While I was casually stepping over a fallen tree on a spring afternoon, a wild turkey suddenly flew out from underneath my feet. The sound and commotion of a 12-pound bird, with a 5-foot wingspan, launching into the air right in front my face, was startling to say the least. It got my attention. My cholesterol levels instantly bottomed out. Thoroughly shaken, I had to sit down on the log for several minutes and compose myself.

Turns out, I had flushed a hen off her nest. On the ground, next to the fallen tree, were a dozen large white eggs nestled in the leaf litter. How I failed to see such a large bird, sitting there at close range, still baffles me. Her muted brown, grey and black feathers blended in seamlessly with the highlights and shadows of the forest floor on that bright sunny day.

In 1890, a British zoologist named Sir Edward Poulton wrote the first book about camouflage in nature. Poulton, an ardent supporter of Charles Darwin, wrote that camouflage and mimicry in the wild was proof of natural selection. Not long after, an American painter, Abbott Thayer, expanded on Poulton’s ideas and began creating photographs and pieces of camouflage art using countershading and disruptive coloration, culminating in his own 1909 book, Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom. Thayer’s illustrations, showing how objects could “disappear” into the background when they were painted in such a way as to cancel out their shadow, became quite popular and soon attracted the attention of the military. By World War I, armies around the globe were incorporating camouflage into equipment and the uniforms of their soldiers. Long gone were the days of Paul Revere and the brightly attired Redcoats.

Camouflage has even become fashionable. Most popular clothing brands offer an array of camo products, everything from hats to wedding dresses, and shoes to underwear (though I am not entirely sure as to what purpose the latter serves). Even luxury lines like Louis Vuitton have jumped in.

Of course, all of this fashion is modeled after animals in the wild and few wear camouflage as well as the nightjars. These ground-nesting birds, of which there are roughly 98 species recognized worldwide, are the masters of cryptic coloration. In the North Carolina Sandhills, three species are found: the common nighthawk, the chuck-will’s widow, and the whip-poor-will. Each year, I celebrate the first nocturnal calls I hear of the whip-poor-will (usually heard around Eagle Springs in late March) as the harbingers of spring and warmer days ahead.

Nightjars are extremely difficult to find due to their cryptic camouflage. As a result, I have very few photographs of them in the wild. Recently, I received a tip from a local biologist about a nesting common nighthawk on the Sandhills Gamelands. He gave me a GPS point and noted that the bird could be found between two small turkey oaks flagged with bright pink tape.

With that information in hand, I ventured out onto the dirt roads of the Gamelands in early June with hopes of obtaining a few images of the secretive bird. Being extremely careful not to disturb the nesting nighthawk, I slowly approached the GPS point and stood back at a distance of over 10 yards when I saw the bright pink flags up ahead. Raising binoculars to my eyes, I slowly scanned the ground between the two turkey oaks trying to locate the bird. Remember those “Magic Eye” paintings that were so popular in the ’90s? It took several minutes of intently staring at the leaves on the ground before I had the “aha” moment of finally seeing the bird.

The thrill of discovering animals hidden in plain sight never gets old. I still recall with great fondness hiking through the woods one spring day and stumbling upon a young white-tailed deer fawn, curled up tightly on the forest floor beneath a canopy of cinnamon ferns, the white spots on its back allowing the hapless mammal to blend in seamlessly with its background.

Then there was the time I saw an American bittern fly up from the side of the road in the Outer Banks and land in a nearby patch of marsh, where it stood perfectly still with its head pointed to the sky. Its mottled brown plumage perfectly matched the surrounding spartina grass.

One winter, years ago, a Pinehurst resident pointed me to a tree where an Eastern screech owl could be seen basking daily in an open cavity about 20 feet off the ground. Even now, looking at the photos of that owl, it is hard to tell the difference between the owl’s grey feathers and the bark of the tree.

When camouflage fails, some animals will resort to the ultimate form of trickery, mimicking death. The term “playing possum” comes from the behavior of the Virginia opossum, North America’s only native marsupial, which feigns death when threatened by predators. As it turns out, a number of our native animals will resort to that tactic as a last resort. Perhaps the most famous “death actor” is the eastern hognose snake. When confronted by a threat, this robust, 3-foot long serpent, with a distinctive upturned snout, puts on a performance that would make members of Hollywood’s Screen Actors Guild envious.

One of my most memorable encounters with an eastern hognose snake happened years ago near West End. One summer afternoon, a family friend phoned to tell me that she had just found a copperhead in the yard. She asked if I could come over, catch the snake and move it to safe spot (i.e., somewhere far away from her). Surprised, and impressed that she did not want to kill the snake, I hurried over. As I said before, I am a sucker for loathed animals.

When I arrived, I saw my friend standing in her front yard pointing to a small snake coiled tightly several feet away. A neighbor, whom she had called in a panic before dialing me, was standing close by with a shovel in hand. Walking over, I instantly realized it was not a venomous copperhead but a harmless eastern hognose snake. My friend nearly fainted when I casually reached down to pick it up. Her face completely drained of color when the snake began to violently thrash about in my hands. It was only then that I informed her the snake was completely harmless and placed it back down on the ground. There, it continued to writhe back and forth, as if in pain, rapidly throwing coils up over its head. Then it proceeded to defecate all over itself. Finally, the snake lay perfectly still, belly up and mouth agape, its tongue sticking out.

Of course, it wasn’t physically harmed in any way. It simply wanted to make itself appear unappetizing. An especially nice touch, I thought, was covering itself with its own poop.

How these death-feigning tactics evolved over eons of time simply boggles the mind. It certainly threw my friend for a loop. I reached down and slowly turned the snake right-side up. Immediately, it flipped back over onto its back, presenting itself once again as the quintessential dead snake. I smiled. Charles Darwin would have been proud.

By Bill Case • Photographs from the Tufts Archives

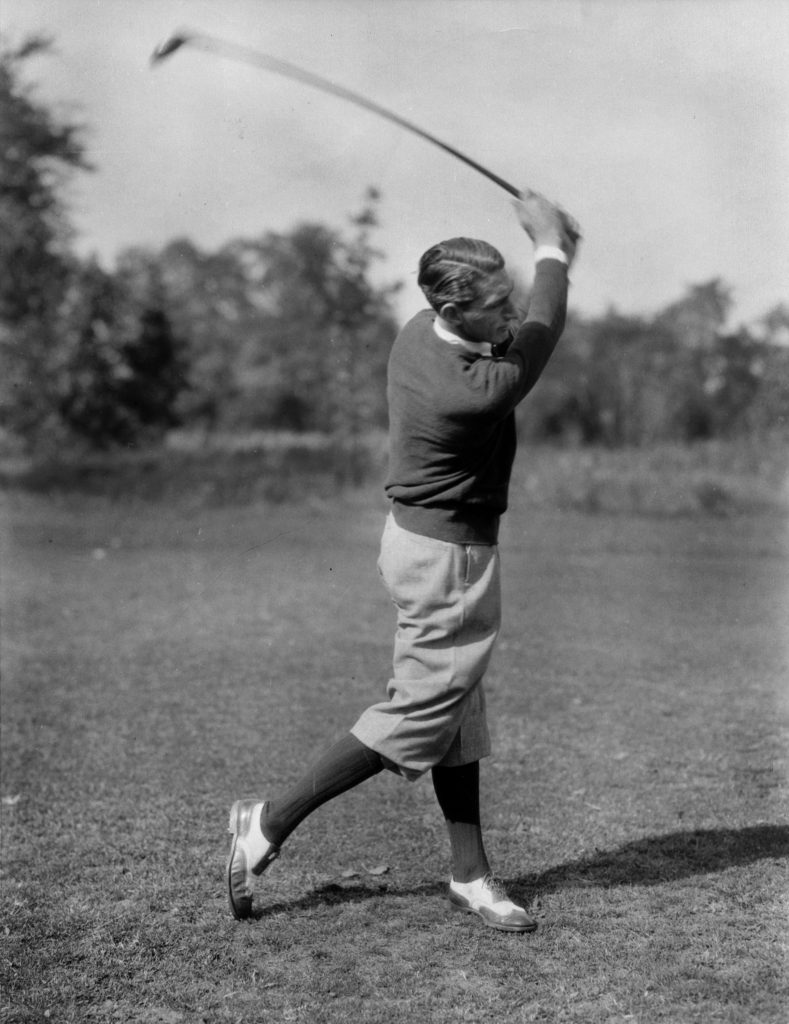

He had survived — a luckier fate than that suffered by millions of World War I soldiers — but his battlefield injuries were grievous. A German mustard gas explosion had totally blinded the young Edinburgh native. One lung was badly burned by the gas. In another engagement, shrapnel from an enemy shell caused serious injuries to his head and left arm, necessitating the implanting of metal plates. Lying battered and helpless in a British military hospital bed, the odds seemed heavily against Tommy Armour ever resuming a normal life.

Serving in the Black Watch Regiment’s tank corps from 1914 to 1918, Armour rose from the rank of private to staff major and achieved widespread notoriety for his machine-gunning prowess. He assembled, loaded and fired his weapon faster than anyone in the Army. This singular talent required superior manual dexterity but, in addition, his hands were remarkably strong: While singlehandedly capturing a German tank, Armour strangled the tank’s commander to death when he refused to surrender.

Prior to the war, those formidable hands had served him well. Among his talents, Armour was a virtuoso violinist and a high-level bridge player, but his favorite pastime was golf. Armour, his older brother Sandy, and lifelong friend Bobby Cruickshank toured Edinburgh’s Braid Hills Golf Course at every opportunity. “In the summer,” Armour later recalled, “I would be on the first tee at 5 a.m. and in the evening . . . play a couple of rounds.”

Throughout his convalescence, Armour kept up his spirits by dreaming of playing golf again. While it took six months, sight gradually returned to his right eye, though he remained blind in his left. The recuperating 23-year-old would play golf again, but could his limited vision scuttle any hope of regaining his previous form? The preternaturally confident Tommy Armour believed otherwise.

Armour joined Edinburgh’s Lothianburn Golf Club with the expectation of not just recovering his game but elevating it. Adapting to his partial blindness, he steadily lowered his scores, though his putting was erratic. The blindness in his left eye was distorting his depth perception. One day, in a fit of pique, he hurled his collection of putters off the Forth Rail Bridge into the firth below. It was these all-too frequent episodes of balky putting that would one day prompt him to coin the phrase “the yips.”

Despite his weakness on the greens, Armour began making his presence felt in tournaments, finishing runner-up in the 1919 Irish Amateur at Royal Portrush. He really raised eyebrows when he won the French Amateur in July 1920. Soon afterward, Armour sailed to New York, looking to test his game against America’s best. While aboard ship he met Walter Hagen, the game’s top professional golfer. The two men found they had much in common: Both enjoyed parties, the company of attractive women, and the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol. As author Mark Frost wrote in The Grand Slam: Bobby Jones, America, and the Story of Golf, the young Scot had a capacity for liquor surpassing his older friend. “Whereas ‘The Haig’ often watered down drinks to polish his reputation as a boozer,” wrote Frost, “Armour’s glass was never half-empty.”

Hagen took the young man under his wing, setting up an exhibition match for the visiting amateur’s American debut. On July 25 the fellow bon vivants squared off against Jim Barnes and Alex Smith in New London, Connecticut. The Armour-Hagen team lost the match 1-down, but The New York Times reported that Armour’s “long driving surprised the gallery,” and that his mashie play “stamped him as a golfer who will be hard to beat.”

In early August 1920, Armour entered the U.S. Open at Inverness Country Club, in Toledo, Ohio, finishing 48th, 22 strokes behind winner Ted Ray. But those who assumed the hype regarding this Scottish upstart had been overblown were in for a surprise two weeks later at the Canadian Open. Playing brilliantly throughout, Armour finished the championship in a three-way tie at the top with Charles Murray and J. Douglas Edgar, eventually losing the playoff to Edgar. The Scot followed that promising finish with another, reaching the quarterfinals of the U.S. Amateur at Engineers Country Club in Roslyn, New York.

While stateside, Armour found time for other pursuits. An October 29, 1920, New York Times article reported that the golfer had wed 26-year-old Consuelo Carreras de Arocena the previous day. A son, Thomas Dickson Armour Jr., would be born to the couple a year later.

Though Armour had played creditably that summer, he had yet to achieve a victory on U.S. soil. That changed in November after he arrived in Pinehurst to compete in the resort’s inaugural Fall Amateur-Professional Best Ball Tournament on course No. 2. The event attracted many leading players, including Gene Sarazen, the aforementioned Douglas Edgar, and Leo Diegel, later a two-time PGA champion.

Already recognized as a tournament hotbed, the Pinehurst resort successfully lured top players for tournaments on their way south for the winter and then again on their way northward in the spring. March and April were the months when the United North and South Amateur championship and the North and South Open were held. The tournaments attracted resort visitors looking to spot their favorites both on and off the course. What could be more appealing to a devout golf fan than encountering the legendary Walter Hagen in The Carolina Hotel bar?

Pinehurst appealed to Armour as well. Partnering with Diegel, the two ham-and-egged their way to the Amateur-Professional title, posting a four-round best ball score of 275. The win provided the Scot a measure of revenge against Edgar, whose team finished runner-up. The euphoric Armour extended his stay, competing in the resort’s match play Fall Tournament. He reached the quarterfinals before bowing to Frances Ouimet. After that, Armour and his bride sailed home to Great Britain.

Back in Scotland, Armour continued to polish his game in amateur tournaments. In May 1921, he joined a team of British amateur stars for a match against a formidable American team that included Bobby Jones, Chick Evans and Ouimet. The informal match, held at Royal Liverpool Golf Club and won by the U.S., drew over 10,000 spectators and sparked the institution of the Walker Cup matches the following year.

Having experienced the good life in America, Armour yearned to return. Following the 1921 slate of British golf championships, he was back in the U.S. competing in tournaments. In October he informed the press he intended to make America his permanent home. Armour’s brother Sandy and Braid Hills running mate Cruickshank also chose to emigrate. The New York Times observed, “The British golf world is faced with the odd spectacle of its previous defenders against American invasions being members of future attacking parties.”

Still an amateur, Armour looked to establish himself in America and, once again, Hagen came to the young man’s aid, making the connections that led to Armour being hired as the secretary of Westchester-Biltmore Country Club in Rye, New York. A sprawling complex, the club featured two golf courses, a polo field, racetrack and 20 tennis courts, built at a cost of $5 million.

Armour’s natural social skills made him ideal for the post. He deftly saw to the needs of the Biltmore’s guests and entertained them as well, regaling patrons with raucous stories evoking paroxysms of laughter. Byron Nelson considered Armour the most gifted storyteller he ever knew. “He could take the worst story you ever heard,” said Nelson, “and make it great.”

Armour’s job kept him busy during the warmer months, but when the weather turned chilly, he headed to Belleair, Florida, where he played numerous matches and tournaments against top players. Convinced he could hang with golf’s upper echelon, he turned professional in 1924. Soon after, Armour became the professional at Whitfield Estates Country Club, a Donald Ross-designed golf course (now Sara Bay Country Club) that was part of a Sarasota real estate project. Lifetime amateur Bobby Jones was also on-site, earning some extra dough peddling lots as the project’s assistant sales manager. Armour played golf daily, frequently in the company of either Jones or Hagen, who was affiliated with a nearby golf community.

In March 1925, Armour won the Florida West Coast Open, his first victory as a pro. With the North and South Open approaching, the triumph did not go unnoticed in the Sandhills. A piece in the Pinehurst Outlook reported that the word coming out of Florida was to “watch Tommy Armour!” The transplanted Scot played admirably in the North and South, finishing fourth.

Though Armour was rapidly progressing up the pecking order of top players, his share of tournament purses was never going to be enough to make a decent living. Even the game’s greatest supplemented their incomes by competing in exhibitions and securing club pro affiliations for both the summer and winter. Armour landed a premier summer gig as pro at Congressional Country Club in Bethesda, Maryland. Over the years, he would prove something of a vagabond in his northerly club employments: Medinah in Chicago, Tam-O-Shanter in Detroit, and Rockledge in Hartford would be featured among his other stints.

Armour’s primary goal, however, was to win tournaments. After two years adjusting to tour play, he skyrocketed to superstar status, winning five titles in 1927, including the U.S. Open held at America’s most demanding course, Oakmont Country Club. Trailing Harry Cooper by a shot as he arrived at the green of the championship’s final hole, Armour faced a birdie putt from 10 feet to force a playoff.

Bobby Jones, who was in the gallery, overheard two spectators debating whether any golfer would be able to successfully handle the pressure of such a critical moment. Jones calmly informed the bystanders that a man who had snapped the neck of a German tank commander with his bare hands was unlikely to be bothered by a 10-foot putt, regardless of its import.

Armour cooly drained it. In his 18-hole playoff victory over Cooper, Armour took just 22 putts over Oakmont’s diabolical greens. Perhaps he wasn’t such an awful putter after all.

The victory, coupled with his charismatic persona, thrust Armour into golf’s spotlight. Tall, dark, handsome and, like Hagen, impeccably attired, Armour, was a hit with the ladies, an attraction he did nothing to discourage. A penchant for heavy gambling, particularly on the course, also drew attention. Golf great Henry Cotton expressed uncertainty as to what Armour liked best, the golf or the betting. “He is not satisfied,” claimed Cotton, “unless he is wagering on every hole, every nine, each round, and if he can, on each shot.”

Augmenting Armour’s swagger was the occasional wearing of a patch over his left eye. He sported the best nickname on tour — The Black Scot — referring to the jet-black hue of his luxurious head of hair.

More victories followed. By the time Armour arrived at Fresh Meadows Country Club in Flushing, New York, for the 1930 PGA Championship, he had eight more tournament titles to his credit, including the prestigious Western Open. In his quarterfinal match at Fresh Meadows against Johnny Farrell, Armour found himself 5-down after six holes before rallying to win. Fighting his way to the championship’s final match, he took on Gene Sarazen in a nailbiter, beating “The Squire” on the 36th hole.

By 1930 Armour’s domestic life was in turmoil. In the course of his wanderings, he had met Estelle Andrews, the widow of an iron manufacturer. They started an affair, a fact unappreciated by Armour’s wife, Consuelo, who responded by initiating a series of lawsuits. Eventually, the differences were resolved; Armour got divorced, married Estelle, and adopted her two teenage sons, Ben and John. “Love and putting are mysteries for the philosopher to solve. Both are subjects beyond golfers,” said Armour.

In 1931, he won what, given his Scottish background, was his most meaningful title, the Open Championship at Carnoustie. An early finisher in his final round and sitting in a distant third place, Armour anxiously sipped whisky in the clubhouse while awaiting the two men ahead of him — Jose Jurado and Macdonald Smith — to complete their rounds. “I’ve never lived through such an hour before,” he told reporters. Jurado and Smith both collapsed, and Armour won the championship by one stroke, giving him a victory in all three of the major championships then available.

The rigors of travel and competition were beginning to take a toll on Armour, hastening the graying of his hair which, in turn, necessitated a nickname modification. Henceforth he was the Silver Scot.

Armour began slowing things down a bit by lengthening his sojourns in Pinehurst. His affection for the town would blossom into a full-blown love affair. His first extended visit occurred in the fall of 1932. After winning the resort’s Mid-South Best Ball Tournament with partner Al Watrous, the Armours, Tommy and Estelle, stayed over at The Carolina for several weeks’ rest before decamping to Boca Raton Hotel and Club, a winter head professional gig Armour would keep for the remainder of his life.

While in Pinehurst, the couple relaxed and socialized like any other guests of the resort. They brought sons Ben and John, both cadets at New York Military Academy, to Pinehurst for the holidays. The couple’s frequent movie attendance at the Pinehurst Theatre was dutifully reported in the Outlook. The Armours attended a dinner hosted by Southern Pines Country Club professional Emmett French, himself a three-time tour winner and runner-up in the 1922 PGA Championship. The Armours reciprocated, inviting the Frenches to dinner at The Carolina.

And, like most visitors to Pinehurst, Armour played loads of golf, generally with excellent players like French, Halbert Blue and poet Donald Parson, all reported in the Outlook. As the Armours prepared to depart Pinehurst in mid-January 1933, the paper recapped Tommy’s sensational scoring: “For a stretch of two weeks there was not one day in which Armour failed to equal or better the par of 71 for the No. 2 course. He had as low as 65 one day, this figure failing by one stroke to equal a round of his last month which tied the course mark.” And Armour revered No. 2, saying, “it is the kind of course that gets in the blood of an old trooper.”

In the spring of 1933, the Armours arrived early for the North and South and stayed two weeks after. Ben and John visited again, and Tommy played rounds with Pinehurst’s young phenom, George Dunlap Jr. Later that year, Dunlop won the U.S. Amateur, attributing significant credit for his victory to Armour. “Watching him play, of course, was a lesson in itself,” said Dunlop.

In December 1933, the Armour family once again celebrated the Christmas holidays in Pinehurst, and Armour was elected an associate member (later designated as an honorary member) of Pinehurst’s venerable golf society, the Tin Whistles. Returning in the fall of ’34, he paired with his boyhood friend Cruickshank to win the Mid-South Scotch Foursomes. After the victory Tommy and Estelle remained in Pinehurst, enjoying an array of social functions and attending the theatre, until the second week of January.

After 1935, Armour was competing only sparingly on tour. He was hired by MacGregor Golf in 1936 and, unwilling to simply sit back and endorse the company’s clubs, actively involved himself in their design. As a result, MacGregor became the industry-leading club manufacturer. “Tommy Armour” brand clubs are still made and marketed today.

Armour achieved fame as an instructor, despite delivering frequent tongue lashings to his pupils. An article by H.K. Wayne described his unique teaching methods: “His preferred style involved sitting in the shade in Boca Raton each winter or in Winged Foot each summer, with his trademark tray of gin, Bromo-Seltzers and shots of Scotch and passing judgment on his wealthy pupils, all of whom feared him.” Armour would subsequently author, with the assistance of golf writer Al Barkow, How to Play Your Best Golf All the Time, a bestseller, still in print.

Armour continued making pilgrimages to Pinehurst. The more time he spent in the Sandhills, the more he rhapsodized about how wonderful it was to be there. His fawning quotes were undoubtedly appreciated by the resort’s public relations department. “I’ve seen strangers, jaded and dull, come to Pinehurst, and after a few days be changed into entirely delightful fellows,” said Armour. Pinehurst’s practice ground elicited quotable praise. “Maniac Hill is to golf,” he asserted, “what Kitty Hawk is to flying.”

In yet another homage, he declared, “I can’t help it. Pinehurst gets me. From morning firing practice at Maniac Hill, to vespers at the movies, Pinehurst is the way I’d have things if it were left to me to remold this sorry scheme of things entirely. . . . It’s the last in the vanishing act of fine living.”

In a sense, Armour promotes Pinehurst even today. Exhibited in the resort clubhouse’s hallway of golf history is a rotating display that provides another Pinehurst tribute from the Silver Scot. It neatly combines in one statement his sentimentality and occasional brusqueness, reading, “The man who doesn’t feel continually stirred when he golfs at Pinehurst beneath those clear blue skies and with the pine fragrance in his nostrils is one who should be ruled out of golf for life.”

When Armour came to Pinehurst in November 1938 to play the resort’s two professional events — the Mid-South Professional Best Ball and the Mid-South Open — he was semi-retired from competition. His last individual tournament victory had taken place three years prior at the Miami Open. Inspired by his surroundings, the 42-year-old rekindled his old form. Not only did he and sidekick Cruickshank tie for the best score in the best ball, Armour won the individual title, too. It would be his 25th and last PGA Tour victory.

One of the few titles to elude Armour’s grasp was the North and South. This gnawed at him both because of his love of the venue and because of the tournament’s prestige. Runner-up twice, Armour dwelled on his near misses, ruminating that “there are five traps on this course (No. 2) that have cost me the North and South five times.” He continued competing in it long past his competitive heyday. He even had a shot at victory after the tournament’s first two rounds in 1948 when his 143 total left him just three strokes out of the lead, but an 81 in round three ruined the aging veteran’s bid.

In 1951, Armour attended Pinehurst’s lone Ryder Cup. It turned into a delightful reunion for the 54-year-old. Longtime friends Hagen, Sarazen and Cruickshank were also on hand, and Armour delightedly joked and hobnobbed with the old stalwarts. When Hagen held a driver for a photo op with his fellow legends, Armour, ever the scolding instructor, pointed out, “You never gripped a club that way in your life!”

The North and South immediately followed the Ryder Cup, and Armour gave it one final try, missing the cut by two shots. The ’51 event also marked the end of the line for the North and South itself — the result of a brouhaha between the PGA tour and Pinehurst resort owner Richard Tufts. He had resisted efforts by the tour to have the amount of prize money bumped from $7,500 to $10,000 — the tour minimum. In response, several American Ryder Cuppers left Pinehurst following the matches, effectively boycotting Tufts’ event. Only one team member, Henry Ransom, completed all 72 holes. Reciprocating the hard feelings, the miffed Tufts terminated the North and South after a 50-year run.

In Armour’s later years, he kept on playing, teaching, storytelling, gin playing, gambling and cocktailing. In a 1978 Sports Illustrated article, Scottish writer and an excellent golfer in his own right John Gonella recounted an experience 30 years before when Armour hosted him at the Boca Raton Hotel. The writer was amazed at how the hotel’s management cheerily indulged Tommy’s every whim, happily picking up a multitude of expensive tabs for him and his parade of guests. After the young Gonella, short on funds at the time, and Armour teamed up to win a golf bet, Armour generously shared the winnings with his broke writer friend.

At lunch in the grillroom afterward, Armour asked Gonella if he would like to meet Walter Hagen. When the reply was affirmative, Armour called to the bartender and commanded, “Get me Hagen on the phone: Detroit Athletic Club, last stool at the left end of the bar. And bring us a phone!” According to Gonella, Tommy had Walter on the line two minutes later, and greeted The Haig with, “Hello, you old has-been. There’s a friend of mine here from Scotland I want you to meet.”

Armour, a 1976 inductee into the World Golf Hall of Fame, passed away in 1968 at the age of 71. Shortly before his death, he shared a visit with his 8-year-old grandson, Thomas Dickson Armour III. The fruit would not fall far from the tree (though perhaps skipping a generation). Tommy III became a fine player himself, winning twice on the PGA Tour and setting a 72-hole scoring record. Now semi-retired from competitive play, Tommy III resides in Las Vegas, where his reputation for living the high life tends to overshadow his golf achievements. He even has his own nickname, “Mr. Fabulous.”

Given his tender years at the time of the childhood visit, it’s understandable Tommy III doesn’t remember much about his grandfather. But it did stick in his memory that the elder Armour was very handsome and, even in the late stage of life, exceptionally strong. Those hands never weakened.

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Gessner

If you think an interior designer’s house should knock your socks off, you’d be right. Especially a designer with international credentials who conceived the house from the ground up and the studs out.

The designer is Liz Valkovics. The location is lakeside, in a gated Pinehurst golf community. The exterior is Carolina casual to blend with surroundings but inside is a magazine layout, contemporary in vision, curated for practicality, incorporating an ice bath and sauna for daily use and wellness events, a ground-level game room with pool table, movie screen, guest quarters and kitchenette. Because . . . sophistication notwithstanding, this house is also home to Luke, 11, Sophie, 4, and golden retriever Gus, whose fur matches the oatmeal-textured low-slung sofa in front of the glowing tubular fireplace. The result: stunning yet comfortable for a young family.

“The kids don’t have to be too careful,’’ Liz says.

Over the mantel a frame surrounds the wall-mounted TV. The whole equals a study in earth tones with a generous nod to black, from set-in houndstooth rugs to matte charcoal kitchen cabinets and a matching Hallman (Italian) six-burner range with a grill top, where Luke and Sophie make pancakes on weekends. Even the quartzite countertops — hard as granite, beautiful as marble — have undulating waves of gray. “I’ve done a purple kitchen but this was for us, no clutter, happy and inviting,” Liz says.

Liz paints. Her choice of art, some digitally achieved, is wide ranging. A computer program that moves furnishings within a room and performs other diagnostics aid her decorating decisions. She studied and taught art, became a full-time painter, and earned a degree from the London School of Interior Design. Her specialty: hospitality venues, restaurants and commercial space. The jewel in her crown is a boutique hotel in Dubai, although she also served as creative director for a Florida hotel, worked in Baku, Azerbaijan, and undertook design projects at London’s Gatwick Airport.