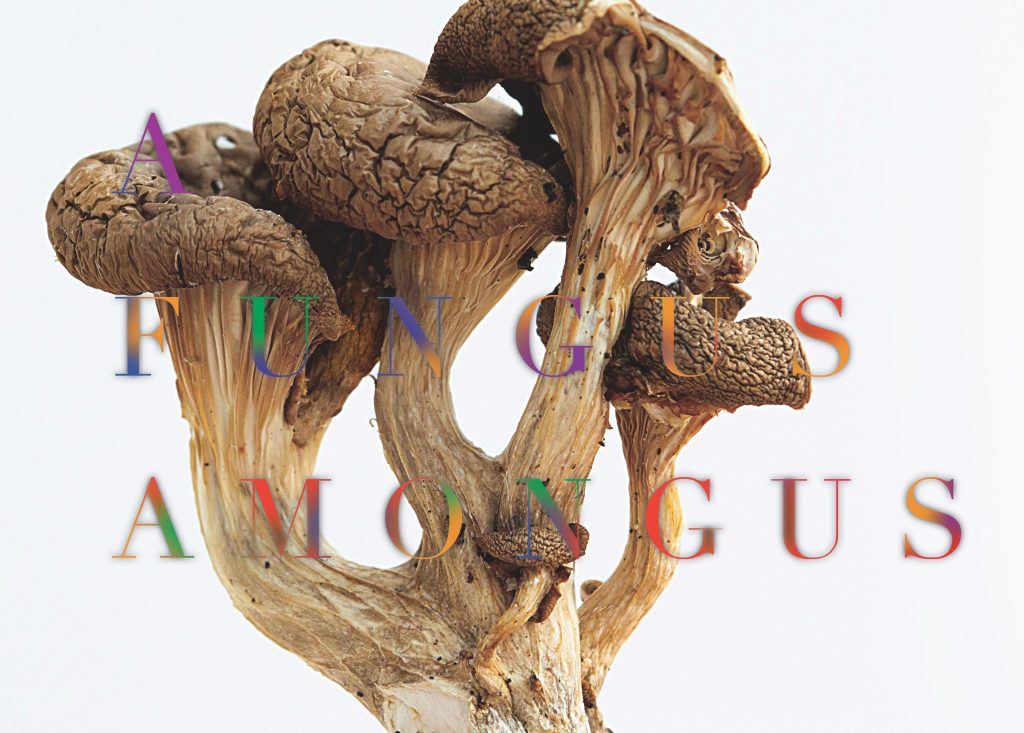

A FUNGUS AMONGUS

A Fungus Amongus

Making ’shroom for a new method of farming

By Emilee Phillips

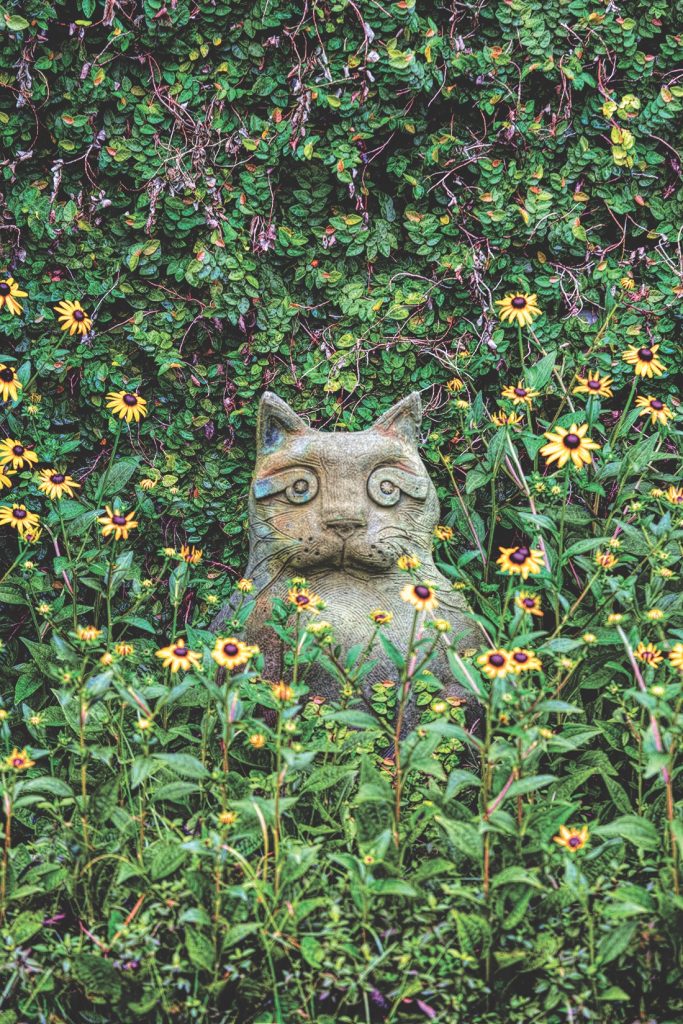

In the dark basement of a sprawling farmhouse, a mother and son work daily — and meticulously — tending to colorful bunches of oyster and lion’s mane mushrooms. Like the natural mushroom systems that grow underground, the labyrinthine basement is laid out in intricate patterns, a maze of rooms, each dedicated to its own phase of cultivation.

The rhythmic routine of misting, monitoring humidity and harvesting is as much art as it is science — a quiet but steady labor rooted in patience and precision only to be broken up by the laughter of a family joke.

In a home that sits on 200 acres of farmland that has been in the family for three generations, Candice Graham and Jonathan Bumgarner have converted their basement into Cranes Creek Mushrooms, breathing new life into empty space.

There is something profoundly grounding about a family farm. In the fast-paced, ever-changing landscape of modern life, the farm represents a constant — a space where the rhythms of nature dictate the pace of life, where the priorities shift from instant gratification to patience. It’s about cultivating a lifestyle that prioritizes sustainability, where food is grown with intention, animals are raised with care, and the land is honored as a precious resource.

Graham inherited the farm from her mother, who wasn’t a farmer herself but had a vision for her children’s future. In an act at the intersection of hope and business, she arranged for 322 pecan trees to be planted that, one day, would tower over the land and provide an additional revenue stream to sustain the farm. Though still young, some of her trees are beginning to produce, her promise literally coming to fruition.

Determined not to see the land broken up and sold off, the family had to get creative. They decided to take a leap into the unknown with mushroom farming. Aside from pecans, neither Graham nor Bumgarner had dabbled in agriculture before. “You take one step forward and three steps back with farming,” Graham says. “There’s a lot of education and research involved.”

Their first summer was trial and error. Beginning outside in a barn, they quickly learned the unpredictability of the effect natural climates can have on fungus farming — an experience that resulted in a complete do-over and driving them inside and underground. One way to bypass the natural limitations of mushroom farming, such as seasonality, is through indoor farming, which allows for year-round production and more control over the finicky crop. Now Cranes Creek Mushrooms produces a variety of oyster mushrooms, including black pearl, elm, chestnut, king trumpet and blue. From start to finish the process takes about two to three months. Lion’s mane — especially prized for tinctures and unique dishes — takes even longer, requiring about five months to grow. The longest part of the process is the preparation and sanitation of everything.

“It’s a very sterilized process, which is ironic considering how much mold mushrooms produce,” Bumgarner says with a chuckle.

The operation begins by soaking wheat grains to use as a breeding ground for the mushroom spores to colonize and reproduce, building vast networks of their root-like structures, called mycelium. Then the spawn is placed into large biodegradable bags and formed into blocks. The blocks are monitored closely after spores are added. These blocks are then arranged on rows of shelves in one of the converted basement rooms, where the mushrooms grow mostly in the dark, changing color from brown to white to nearly black, and then back to white again. In the wild, this part of the journey would happen underground.

“If it gets just one little germ in it, it multiples,” Graham says. If at any point in the process something appears wonky, the entire bag must be discarded. It’s survival of the fittest for these fungi. “You have to keep an eye on them every single day,” she says.

In another room, the next phase begins in large inflatable tents equipped with zippered doors and climate control. This “fruiting” space is lined with shelves of carefully arranged grow blocks that sprout with alien-like forms. Mushrooms thrive in humidity, but the temperature must be carefully managed. “A lot of people think mushrooms grow in the dark, but they actually crave light,” Graham says.

The family works in the tents wearing masks to avoid inhaling too many spores in the confined space. “A lot of it is about the tedious little things,” Bumgarner says.

“None of the labor is hard; you just have to keep an eye on them. It’s like having little babies,” Graham says.

Just days after the fungi begin emerging from the mycelium bags, they’re ready to harvest. For Bumgarner, the most satisfying part is twisting off a large clump of mushrooms, a small and crisp snap accompanying the plucking. Oyster mushrooms sprout in delicate clusters, their soft, fan-shaped caps unfolding in shades of pale cream or dusky blue-gray, like the soft brushstrokes of a watercolor painting. The bushels vary in size, resembling bouquets of flowers.

Just as mushrooms seemingly pop up out of nowhere, so too has their rise in popularity. With growing awareness of their health benefits, mushrooms were named “Ingredient of the Year” by The New York Times in 2022. At the Moore County Farmers Market in Southern Pines, Graham and Bumgarner regularly set up their booth with a selection of oyster mushrooms, lion’s mane and mushroom tinctures, all far from your average white button mushroom. They take the time to educate the curious about the complexities of mushrooms, whether for cooking or as tinctures. “We’re met with a lot of curiosity,” says Graham.

Every week, it seems, the duo find themselves explaining the benefits of lion’s mane mushrooms with their distinctive, almost otherworldly appearance — long, white, hair-like tendrils resembling the mythical abominable snowman. Despite the growing buzz around their potential health benefits, Graham and Bumgarner are often surprised when people haven’t heard of lion’s mane. Graham takes tincture droplets daily, which she believes improves memory and reduces inflammation. For them, mushrooms aren’t just a culinary ingredient; they’re a form of nature’s medicine.

The two are also experimenting growing rieshi mushrooms, which are thought to help aid relaxation. “Everyone needs to relax more,” says Graham. Mushroom-based products like mushroom coffee have been gaining popularity in recent years, but Bumgarner believes tinctures are the way to go. “They’re more potent, pure, and taste better,” he says. Cranes Creek Mushrooms soak their mushrooms in pure vodka to make their tinctures.

Oyster and lion’s mane mushrooms are seldom found in traditional grocery stores. In many ways, they are a quiet luxury, accessible to those who shop with intention at places like farmers markets and co-ops. Their luxury isn’t due to high cost or rarity, but rather their shelf life, which makes them less suited for conventional grocery store environments.

In addition to the farmers market, you can find Cranes Creek Mushrooms in gourmet dishes from local restaurants such as Ashten’s and Elliott’s on Linden. For Bumgarner, nothing beats the simplicity of sautéing mushrooms in butter. He and his mother agree that lion’s mane has a more unique texture, almost chicken-like, with a flavor that is difficult to explain to someone who has never tasted it. “It’s meatier,” he says. “One of the most interesting things I’ve learned about mushrooms is that you don’t get any of the benefits, other than fiber, unless you cook them.”

Graham says the shared mother and son moments are one of the most rewarding parts of their business. “We get a lot of family time. We can tease and talk and work.” As someone passionate about eco-friendly practices, Graham was thrilled to learn about the benefits the mushroom spawn blocks could bring to the soil on the farm.

Along with mushrooms, Graham and Bumgarner have added quail and chickens to their operation, knowing the extra minerals and nutrients from the spent mushroom blocks can aid the overall health of the animals on their property. “We are trying to get to the point where the farm supports itself,” she says. “I also have to stay busy or I’m not happy.”

More than a business, Cranes Creek Mushrooms is life underground, a labor of love, fueled by family.