Songs of the Season

With faith of his father, Dixie Chapman made the journey from the course to the choir

By Jenna Biter

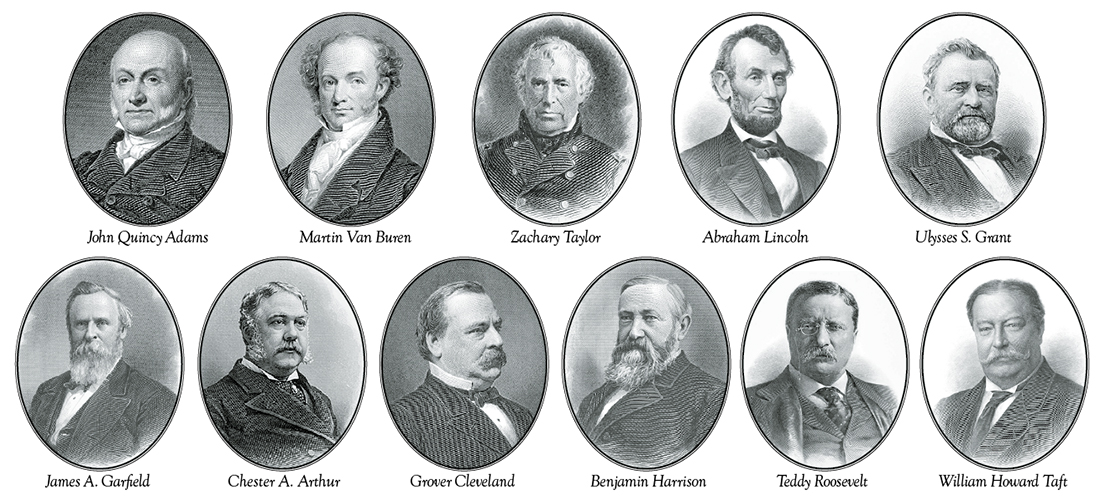

Dixie Chapman walks me through the open floor plan of his home to the sitting area: a plush-looking sofa across from twin armchairs. Paintings of a sun-drenched farm scene and a portrait of a bearded man I feel I know hang on the walls. The room itself is a warm conversation, if a room can be such a thing. I pick the plush-looking sofa, and he takes a chair opposite. I wonder if it’s his favorite and look him over: silver hair combed to the side, dark-rimmed glasses, a gray turtleneck, quarter-zip pullover, stone khaki pants, polka dot socks peeking out beneath pant legs, golf sneakers.

He wears the ensemble comfortably, like a faithful uniform. And, in a way, it is his uniform. He’s a golfer and has been his entire life. With famed amateur golfer Dick Chapman as his father, he almost has to be. But Dick Chapman is a story for another day.

Richard Davol Chapman Jr., better known as Dixie, is a golf lover like his dad. He plays four times a week, weather permitting, and resides with his wife, Pidgie, on the grounds of the Country Club of North Carolina in an elegant, easy home tucked away under trees on the bend of a road with a garden oasis for a backyard. “We’re very happy,” Chapman says. “It’s a great house as far as flow is concerned. You go here and there, and it’s not complicated at all.” Uncomplicated — that’s how he seems to live his life, rooted in his marriage and balanced by golf, his career as an investment manager and his expression of faith: hymn writing. “I’ve got a nice little triangle there,” he says.

Chapman was born into music almost as much as he was born into golf. “I’ve always liked to sing. We went to The Village Chapel when I was growing up. My father actually became the choirmaster, and he had a very good voice. I kind of grew up with music.”

He pauses. “I tried to learn the piano but that never worked; my fingers are too short.” Holding up his hands in a piano spread, he laughs. “They never flew . . . no, no, no.” Chapman shakes his head and smiles. “But we had an organ in the house, a small organ; my father played. And we had a piano; my mother played show tunes.”

Chapman studied English in college and has written poems throughout his life. A couple of decades ago, Johnny Bradburn, the music director of the church he was attending, read his poetry and liked what he read. He asked Chapman if he thought he could write a hymn.

“Well, I don’t know. I never tried to do that,” Chapman responded. “Lo and behold, the first one I wrote, the choir sang. And I was out of town.”

He and the music director began collaborating on hymns. “He had the unique ability to write,” says Chapman. “I would sing to him, and we would go over lines and over lines, and he’d get the melody, and write it down. Put it into musical notation. So then, when I sang a solo, he would play the music.

“I’ve written, I don’t know, 140 or so hymns since then,” he says. Adding with a laugh, “I’m not on the same level as Charles Wesley, who wrote 6,000.” While Chapman admires Wesley, an 18th century leader of the Methodist church, he doesn’t aspire to be as prolific. “I don’t want to write one every day.”

I ask if he finds writing hymns relaxing. He hesitates and says, “Well, it takes attention, and it’s exciting. I enjoy it thoroughly.” Then he tacks on, “It’s relaxing when I finish it.”

Sensing that he doesn’t want to turn his worship into a chore, recuperation between hymns seems necessary, even if it’s only a pause to enjoy a completed song. “Some take me longer to write than others, and I’m always revising. It’s never going to be right the first time you do it. You have to keep revising and improving the metrics, improving the words that you want to use,” he says. “It’s an interesting process. I’m just waiting to hear the next one.”

Chapman usually writes when he feels a nudge. “A line will stick with me. Sometimes it just comes out of the blue, and I hear something in my head, and the spirit guides me.” Sometimes Pidgie is the nudge. She often prints out familiar songs for her husband to mark up and transform. “I like to take a melody from a well-known song and incorporate it into a religious song,” Chapman says.

He’s got a hymn for Lent. It’s called “Vigilant.” He pauses, clears his throat and begins to sing. “Vi-gil-ant. Be viiiii-gilant,” he trills up and then down, holding onto the words. “The day of the Lord will soon begin,” he sings and then shifts back into speech to explain the accompaniment for this particular hymn. “It was all brass of course. And that song went so well with that.” Then he picks up where he left off. “Vig-il-ant. Bah, bah, bah, bah . . . ” He imitates blaring brass and trumpeting trumpets. “Ta, ta, ta, ta . . . you know?” He’s a musician lost in the song.

We run through a list of seasonal hymns. Chapman hums low, testing out melodies before belting into song. “No,” he mutters and adjusts his tone. He taps his foot for time, polka dot socks coming in and out of view. He sings through four or five songs. “Do you still have someone to write music for you now? Are they still performed?” I ask.

“No, I wish I did, but I don’t. It’s frustrating.” Chapman frowns. After leaving the church with the talented music director for a new spiritual home, he hasn’t had many opportunities to share his songs publicly. One day, though, he hopes to combine 10 or 20 of his favorites into a booklet and publish them.

“Vi-gil-ant. Be viiiii-gilant.” PS

Jenna Biter is a fashion designer, entrepreneur and military wife in the Sandhills. She can be reached at jenna.biter@gmail.com.