Jump-starting a financial giant

By Jim Moriarty • Photograph by Tim Sayer

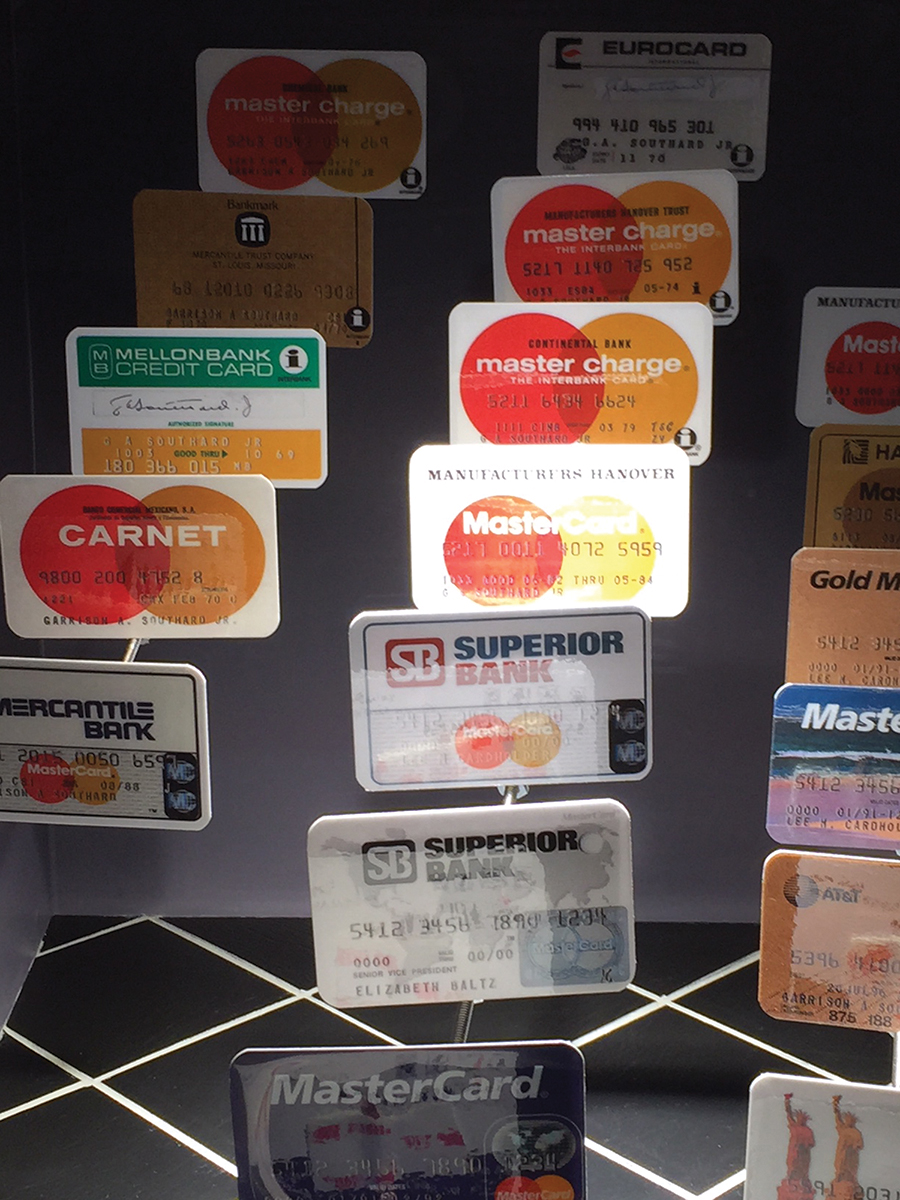

If the U.S. Postal Service has to use a forklift or your internet provider has to double its bandwidth to deliver your MasterCard bill after the holiday season you really have no one to blame but yourself. However, if you did feel the need to look around for a convenient scapegoat, look no further than Gary Southard. It wouldn’t be strictly accurate to say that Southard invented MasterCard, but it wouldn’t be entirely wrong either. It’s a bit like asking which Wright Brother invented manned flight. At the end of the day, the hang time is what really mattered — even if decades down the line you end up hoisting your credit limit on Southard’s petard.

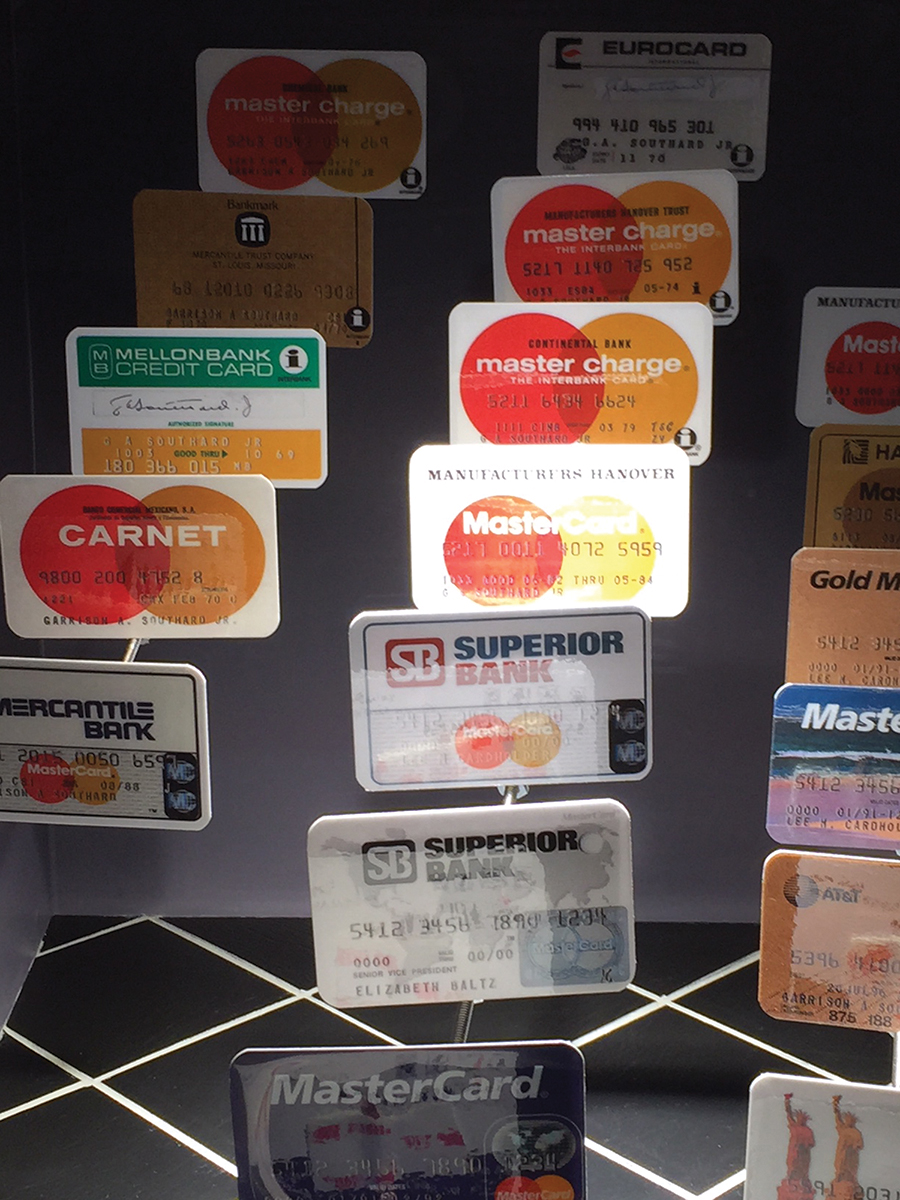

Southard, who has lived in Pinehurst with his wife, Sue, for the past 20 years, was the first president of the operating company that administered Master Charge, an infant venture of four California banks that would eventually metamorphose into the MasterCard behemoth that employs something in the neighborhood of 12,000 people today. Southard strolled into the picture somewhere at intersection of serendipity, salesmanship and destiny. “In November of 1966 I was hired from State Street Bank in Boston to go and do the start up, bring this company operational,” says Southard. “So I was the first employee and had the great title of president.” Today, MasterCard ads saturate TV and its billboards are ubiquitous in airports around the world. When Southard saw one in Dubai, his reaction was positively grandfatherly. “I didn’t feel it was my child,” he said, “but I have a warm place in my heart.”

Born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1929 (yes, the man who helped get MasterCard off the ground was born the same year the stock market crash rang in the Great Depression) and grew up in Robinson, Illinois, home of the Heath candy bar. He attended the University of Illinois, was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps and is a veteran of the Korean War. In March of 1953, he joined IBM where he quickly found himself seated on the same dais with Tom Watson Sr., the company’s benevolent dictator, and his successor, Tom Watson Jr., being fêted as their salesman of the year. After a brief stint with RCA where he and 18 other IBM refugees made a mostly unsuccessful attempt at starting their computer division, he joined State Street Bank in its mutual fund group.

The four California banks that ultimately moved him from one coast to the other — Wells Fargo, Crocker, UCB and Bank of California — didn’t want to be in the credit card business at all but felt they couldn’t avoid it since Bank of America introduced its card, BankAmericard, in 1959. Rather than issue cards separately, they wanted something with a common card face. With Southard’s help, they formed a company to accomplish just that. Its success kicked off a lot of begetting. The California Bank Card Association (the first venture of the four banks) begat Western States Bank Card Association, which begat Interbank Card Association (when the big Eastern banks joined in), which eventually morphed into MasterCard. The entire process took something in the neighborhood of a dozen years and left a footprint in the buying and selling of goods as big as Sasquatch’s.

“The actual first Master Charge card went in the mail on July 7th, 1967. They issued cards to all their checking account holders in good standing,” says Southard. “Theft from mailboxes became a problem. When we started out, we had four Keystone Cops from L.A. as our security.” One of the banks even issued a card to: Jesus Christ, Church of the Latter Days Saints, Alameda, CA. “To the best of our knowledge, it was never used,” says Southard. It wasn’t just security that was primitive. Merchants had to physically look in a printed ledger to see if a card was still good. “What MasterCard is today, they handle 68,000 transactions a second. They do all the authorizations,” says Southard. “Visa and MasterCard are technology companies. We started with punch cards. Young people never heard of punch cards. It was pushing a lot of paper.”

The now famous interlocking circles on the face were the design product of a Los Angeles ad agency, Foote, Cone and Belding. “Then they had the colors of burnt orange and ochre,” says Southard. “Our board of directors was five at California Bank Card Association at the time. The vote was 4 to 1. The one against was me. I would never have made it in the advertising world.”

If Southard was a Wilbur or an Orville, Karl Hinkey, a top executive at Marine Midland Bank from Buffalo, New York, was the Godfather. He wanted his cardholders to be able to use them when they traveled to California. Enter Interbank and all the big boys — Midland, Chemical Bank, First National City Bank (Citibank), Manufacturers Hanover. “Because Master Charge had been so well accepted throughout the west, they decided it would become the common card for Interbank Card Association,” says Southard, who left his home a block from the Presidio Wall in San Francisco to move to New York to run it. And the rest is history, or at least commerce. Mexico, Japan, Canada and Great Britain all began accepting the card. “The growth was amazing,” says Southard.

By 1973, Southard had moved on to form his own consulting business which he kept up until he retired. Why not? By then he knew most of the big bankers at most of the big banks in the U.S., if not the world. He had three children, Gary (Ry), Susan and Jonathan who rarely lived in the same place long enough to learn their teachers’ names. “Military families stayed put more than we did,” says Ry jokingly, who has moved to Moore County and is a fund-raiser for the Boys & Girls Club of the Sandhills in Southern Pines. “I lived in 18 homes before I graduated from high school. Nine states. Twelve school systems.”

If anything, this nomadic existence seems to have had a distinctly artistic influence on Southard’s three children. Ry went to the San Francisco Art Institute where he majored in photography and minored in sculpture and painting. “I’m an artist,” he says, “but I didn’t want to be a starving artist.”

Susan, who moved to Southern Pines last year, is the founder and director of the Phoenix-based Essential Theatre, now in its 28th season. She has a Master of Fine Arts from Antioch University and is the author of Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War for which she received the Dayton Literary Peace Prize and the Lukas Book Prize, both in 2016.

And Jonathan, the youngest, has a degree in theater from Trinity University in San Antonio. “I was a child actor starting at 6 or 7 years old,” he says. “Never anything big. In Rogers and Hammerstein musicals or Damon Runyon comedies I was ‘the kid.’” Now, the kid’s resume includes being first assistant director on somewhere between 75 and 80 feature films, including Titanic. “I’m about to start my 10th film with a company called Emmett Furla Oasis, very prolific action filmmakers,” he says. It’s a movie starring Sylvester Stallone. “I just did one with him last spring, Escape Plan 2.”

That the children of someone who spent a lifetime in the financial world would find their way into the arts may not be all that odd. Following his divorce in the early ‘70s, Southard was working with First National Bank of Chicago as a consultant when he met Sue who has four children of her own. They would marry 10 years later. “She found a lovely apartment for me on the Gold Coast,” says Southard, so he moved from Manhattan to the shore of Lake Michigan. While he lived in Chicago, if he wasn’t busy walking the city’s famous baseball announcer, Harry Caray, home from a routine pit stop at Sage’s, a local watering hole, Southard became a patron of the arts for the Steppenwolf Theatre Company, using his business acumen to take it from a glorified community theater to regional and national success.

“I was asked to join the board and got involved with fund-raising,” says Southard. “We had these great actors, but we didn’t have enough money to pay them. A lot of them were working two, three jobs trying to stay alive. Gary Sinise. John Malkovich. John Mahoney, who played the grandfather on Frazier. Jeff Perry who’s now with Scandal. Terry Kinney who is directing a play on Broadway. Laurie Metcalfe who’s got a Tony. Sue and I used to take them out to dinner to feed them. We had an open house at the little theater, and we’d bring gallons of jug wine. You’d have guys like Roger Ebert there. We started raising money. AT&T had a big headquarters in Chicago. Eventually, they wound up giving $500,000 and that really put them on the map.” Since Gary and Sue moved to Pinehurst, a village they remembered from a trip to take tennis lessons, Gary has served as president of the board of the Ruth Pauley Lecture Series for four years and another six on the Arts Council of Moore County.

Apparently, he had lots of credit to go around. Like Jonathan says, “I didn’t understand, really, until my adulthood the impact of what he was doing.” If you need a reminder, all you have to do is check your statement. PS

Jim Moriarty is senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.