Cottage Colony Redux

Caribbean colors heat up village landmark

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Gessner

Pinehurst: Retirement nirvana for the fortunate few who have played the best courses, traveled the world, appreciated good food, good company and reasonable health.

That would be Carnie and Sharon Lawson.

Previous inhabitants — together or separately — of impressive Northeastern residences, the Lawsons found an original Tufts-built “cottage” already upgraded, remodeled and enlarged to the hilt with exquisite taste in the village center. While rocking on their front porch they can smell the spices wafting from Theo’s Taverna, watch guests arrive at the Magnolia Inn, and wave at friends strolling by on an autumn’s eve.

Ah, the very, very good life.

But wait: A surprise lurks inside The Oaks, as their home is named. Imagine hibiscus blossoms on a holly bush. Hot pink, acid green, lemon yellow, cerulean blue, aquamarine and coral splash across fabrics and walls in rooms furnished with carved mahogany, inlaid cherrywood, 19th century tables and chairs, bureaus and cabinets, desks and breakfronts — a titillating juxtaposition that works. One created by New Englanders (Connecticut and Massachusetts) who for years wintered sea and land in St. Lucia.

Note the 4-foot model of Carnie’s boat, La Gitane — French for “gypsy girl” — that he hopped aboard after retiring from the financial world at 47. “My parents died young. I wanted to enjoy life,” says the man 37 years later.

A closer inspection reveals a décor composed of more than souvenirs. Between them Sharon and Carnie have five daughters and nine grandchildren whose photos cover tabletops, shelves, walls. Their original art reinforces the Cole Porter lyrics for Anything Goes. Over a luxurious down-filled sofa, upholstered in a Chinese print, hangs a nouveau folk art canvas of four derrières lined up at a bar. It was painted by Sharon’s daughter. Carnie smiles. “I call it beach buns.”

Flanking the fireplace in a smaller gathering room is a year-round, table-top Christmas tree. The two rooms are ground zero when the Lawsons entertain.

Elsewhere, a collection of tiny Limoges pillboxes covers a tabletop. A display of Chinese dragon roof ornaments is arranged on another. Big metal Tonka trucks fill a bookcase. Miniature clowns cavort in a shadowbox. Masks from carnivale in St. Lucia appear here and there. Even a ceiling fixture has a history, removed from the Île de France, the first ocean liner built after World War I, launched in 1926.

Who needs to dream about a Tuscan villa when you’ve got 6,000 square feet (including five bathrooms, some with original claw-foot tubs) of prime Pinehurst real estate, all of it utilized when the children, their spouses and grandchildren gather for Thanksgiving, filling the house proper, the guest quarters and an apartment over the garage?

Yet, what grabbed Sharon’s attention on first perusal was the wallpaper, practically everywhere, with Asian/Indian/Indonesian motifs: lions and tigers and costumed natives; wild flora and fauna that riot across the walls, enlivening a small under-the-stairs powder room, a windowless kitchen, and a sunny master suite.

“We’ll take it,” Sharon said in 2010.

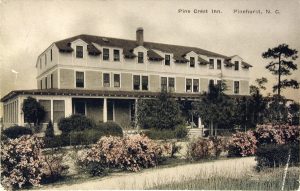

James Walker Tufts would not recognize the simple four-room cottage first dubbed The Nest (no kitchen, no bathrooms, no electricity or central heat) he built in 1896, the same year as the Magnolia Inn, for approximately $1,600.

The Nest was renamed The Crown when it doubled in size in 1901. That’s also when it was occupied by J. Ernest Judd, D.D.S., operating the Crown Dental Parlor, described as “a completely equipped establishment for up-to-date and sanitary dentistry which removes the terror of dental operations.” Among its modern features was a “fountain cuspidor.” Sir Laurence Olivier in Marathon Man would have been envious. Or not. The house was redubbed The Oaks by 1902.

Among other early residents were Fredrick Bruce and his spinster sister, Mary Bruce, a socially prominent duo from New York who purchased the home in 1907. A year later landscape architect Warren Manning created the much-admired garden behind the house. After the death of his sister, Fredrick continued living there until he passed away in 1928. Subsequently, the cottage was sold in 1931 to what seems to be a rather short-lived organization called The Oaks Club. Membership dues were $100 a year, $125 for non-residents. Coincidentally, perhaps, Prohibition ended on Dec. 5, 1933, and in 1934 the house was bought at auction by Franz Hugo Krebs, a Northeasterner who had been a frequent guest at the Holly Inn.

Cathy and the late Bill Smith, of the Southern Pines Ford dealership, accomplished a further enlargement, remodeling and retooling of the home in 1996, its 100th anniversary, with wallpaper added by interior designer and resident Cassie McCord.

The result: a modest frontage behind a picket fence that spreads backward into an outsized — by cottage standards — house with a fenced garden, home to a fountain, a pineapple (symbol of hospitality), light stand and five birdhouses.

Carnie knew Pinehurst from a family golf jaunt when he was 10. He and Sharon were dividing their time between homes in St. Lucia and Chappaqua (New York) when they decided to consolidate, settle down, and trade sailing for golfing.

“Where would you like to live?” Sharon asked her husband.

“How about Pinehurst?” he answered, recalling a resort community resembling a New England village but with a temperate climate.

Sharon had grown up in a historic house. She appreciated that component but wasn’t ready to take on a renovation. Been there, done that. She wasn’t keen on a gated community either. Carnie didn’t want a swimming pool. Been there, done that, too. But they both appreciated a house with character and found one in this extended cottage with its convention-defying layout.

“I have no idea what this was supposed to be,” Carnie says of a room between kitchen and sunroom, itself an addition. Perhaps for dining? Happily, they owned a billiard table (constructed in 1896, same as the house) to fill the space while allocating formal dining to a smallish octagonal music room with built-in china cupboards and woodwork transplanted from a house in England.

Remembering that Tufts’ “cottage colony” homes had no kitchens — guests ate at the Casino building, a communal dining hall — the one added to The Oaks falls outside contemporary glamour norms. Raised-panel cupboards are painted a pale yellow, more pineapple than lemon. A black ceramic tile backsplash adds an art deco touch. In the absence of windows, natural light is conveyed through skylights. A rack holds wide, brightly colored service plates from St. Lucia. The kitchen’s main attraction is an Aga range, the Rolls-Royce of appliances, crafted in the United Kingdom from a Swedish prototype, which cooks with radiant heat and is always “on.”

Outside the kitchen, a dining deck with long table and retractable awning suits a crowd.

Up a narrow flight of stairs, the bedrooms, done in white and pastels, offer the freshness of a Nantucket Bed-and-Breakfast. Queen Victoria may have reigned when The Oaks was built, but her era doesn’t dominate its rooms, awakened instead with the vibrant island hues common to the queen’s contemporary, Paul Gauguin.

Not all retirees choose to live on a bustling lane within sight of shops and bistros. Some want a compact layout, on one floor. Sharon and Carnie Lawson still require space for possessions and memories. “I like to sit and look around; each piece reminds me of something that happened. I call this a big little house,” says Sharon.

“I loved living in St. Lucia and New Hampshire,” adds Carnie. “The people have lived there for many generations. But here, everybody’s from someplace else . . . they are open to new friendships.”

And the feeling is mutual. PS