How the Colonial Kennedy long rifle factory in Robbins became one of the largest in the South

By Bill Case • Photographs by John Gessner

More than 50 years ago, three men clambered down the steep bank of Bear Creek in Robbins hoping to discover artifacts from a frontier rifle factory that, along with its owner, David Kennedy, vanished around 1838. Arron Capel II, now the retired CEO of his family’s century-old braided rug manufacturing business in Troy, teamed with Pinehurst psychiatrist Don Schulte and candlemaker Carl McSwain to conduct what amounted to an archaeological dig. Each possessed an abiding interest in the legendary Kentucky long rifle, which became the gun of choice for America’s frontier settlers and fighting men after gunsmiths of German descent began producing them in southeastern Pennsylvania around 1719. Those artisans discovered that combining a rifled cylinder in the bore of a 4-foot-long barrel dramatically enhanced a gun’s accuracy at previously unimagined distances. British soldiers experienced the lethal power of the rifles when patriot sharpshooters, firing from 250 yards away, toppled redcoats like tenpins during the Revolutionary War.

Because the entirety of the frontier was sometimes referred to as “Kentucky,” the rifle became associated with that area even though long rifles were never actually made there. Ambitious entrepreneurs spread production from Pennsylvania to Virginia, and finally outlying areas like the interior of North Carolina. One of those rifle makers was David Kennedy’s father, (John) Alexander Kennedy, a Philadelphia gunsmith of Scottish descent. The precise date Alexander moved his family by wagon train from Philadelphia to North Carolina is difficult to pin down. One account suggests he arrived in this area as early in 1768 — the year of David’s birth. Family lore says Alexander left Philadelphia to steer clear of the British Army, poised to seize the city in 1777. Concerned that the British would identify him as an arms supplier to the rebels, Alexander usually refrained from engraving his name on rifles he made. Only one bearing the signature “A Kennedy” is known to exist, but his rifles were employed by the Continental Army in the Revolutionary battles of Guilford Courthouse and Kings Mountain.

When he arrived in what is now Robbins, Alexander Kennedy befriended fellow riflesmith William Williamson, who helped Alexander start his own operation by loaning him assorted gunmaking tools. He then taught his trade to son David. Around 1795, David began his own business partnering with Williamson in the operation of a gunmaking facility on Bear Creek.

The partners erected a dam across the creek, diverting the water flow to millworks where the stream’s force powered a waterwheel that, in turn, operated the mill’s machinery. Iron flat bar was rolled into the form of rifle barrels by large grindstones produced by a neighboring millstone maker. The metal was hot-forged and molded into barrels by trip-hammers, likewise operated by waterpower. The barrels (referred to as the gun’s “soul” by Arron Capel) were then “cooked for days at a time and stacked like firewood.” Coal from a nearby mining works supplied the heat source. Brass fittings were cast at Bear Creek too. Once the guns were assembled, they were test fired over the millpond to a target and the rifle’s sights carefully adjusted.

As Capel points out in his book, Bear Creek Long Rifles, there existed a high demand for effective weaponry since, “(in) addition to the obvious need to put food on the table, every frontiersman had the responsibility to protect his family from hostile Indian attack.” Moreover, the Kennedys’ rifle mill and smithy were strategically situated to serve as an outpost for intrepid pioneers departing from Fayetteville (then Cross Creek) and traveling the adjacent trail on their journeys to Salisbury and destinations farther west. It was not long before David Kennedy bought out Williamson’s interest and, with his father aging, became the man fully in charge. Soon, he expanded his holding to include a sawmill, and lumberyard. Five of David’s 10 children, along with his brothers Alexander and John, busied themselves making rifles, pistols and swords. Woodworkers, carvers, engravers and silversmiths crafted the finishing touches that gave Kennedy rifles their unique look. Virtually every component, aside from flintlocks imported from England, was fabricated and assembled at Bear Creek. So many skilled artisans were employed at the bustling mill, the site became known as Mechanics Hill, and a post office by that name was opened. It was the first name given to a settlement that over the following century and a half would undergo name changes as frequently as a flimflam man, identified, in turn, as Elise, Hemp, and finally Robbins.

David Kennedy was resourceful in finding ways to trim costs. Blackwell Robinson’s The History of Moore County — 1747-1847 recounts the local legend of how Kennedy circumvented payment to a New York company of what he deemed to be outrageously high-priced gunlocks. After journeying on horseback to the factory and using his greatly admired violin music to ingratiate himself with the workmen and operators, David “soon discovered the secret involved and returned to Mechanics Hill, where he began to make his own.” And the craftsmanship didn’t come cheap. The most highly ornamented rifles, according to Robinson, “contained silver melted from 16 silver dollars and sold for proportionately higher prices.”

No definitive proof exists that Kennedy succeeded in landing a major contract to supply arms to the U.S. during the War of 1812, but Capel and his friend Bruce Turner unearthed correspondence at the Archives of the War Department in Washington sent by Kennedy in January 1812, to North Carolina Congressman Archibald McBryde. In a letter, Kennedy expressed his willingness and readiness to manufacture whatever numbers of rifles and muskets the government might require, writing, “Tho I am not ancious to under take the bisness, as I am content with my present imployment, which a fordes me a cumfortabel livin….., when I think on the blessings we injoy in our much beloeved country, it makes my hart glo with the love of the same and makes me willin to incounter almost any hardship in defence of our rights.”

Capel maintains there would never have been the “sudden and dramatic increase of employment at the rifle mill (150 workers, according to the estimate of Walter Williamson, William Williamson’s grandson)” absent the procurement of such a deal. In his dogged research, Capel also discovered ancient military records mentioning that a wagonload of Kentucky rifles “had been shipped from the north,” to General Andrew Jackson immediately prior to the Battle of New Orleans — the final engagement of the conflict — and surmises that the wagonload is as likely to have come from Mechanics Hill as any other location.

Whether Kennedy supplied armaments for the war effort or not, it is clear his factory was a booming moneymaker. Robinson’s history asserts that the factory “was the largest in this part of the south.” One contemporaneous account reported the profits of David Kennedy at about $15,000 annually and those of his brother “about 1,000 per annum.” If Google’s inflation calculator is to be believed, that $15,000 represents something in excess of $250,000 today.

Kennedy became an influential personage and benefactor in Mechanics Hill. According to the 1830 census he owned a large plantation consisting of 23 people, including 15 slaves. He and brother Alexander were trustees of the Mount Parnassus Academy in Carthage. David donated land and financed the building of the Mechanics Hill Baptist Church, located on Salisbury Street in Robbins, where the Woodmen of the World Hall now stands. He served as a deacon in the church. A Bible donated by Kennedy in 1823 contained the following tongue-in-cheek inscription: “David Kennedy — his book he may read good but God knows when.”

Kennedy’s religious inclinations may have been galvanized by a harrowing close call. Nearly crushed by a rolling log at the sawmill, David “declared that ‘if the Lord let him live he would use his logs for better purposes,’” according to Robinson’s Moore County history.

Business slowed at the Kennedy rifle factory after 1825, a period of a generally declining economy culminating in the depression known as the Panic of 1837. Making matters worse was the ongoing presence of competitive rifle mills near Salem and Jamestown, North Carolina. The real coup de grace for Kennedy occurred around 1835, when he faced a demand to make good a surety for payment of a large debt owed by brother Alexander, whose general store had failed. David and wife Joanna were ruined and their holdings liquidated. According to Capel’s book, “one 300 acre tract of Kennedy’s land sold for four dollars.” Ironically, gold was later discovered on it. The rifle mill was closed and auctioned off. The buyer converted the facility to a grain mill.

Creditors never ceased hounding David Kennedy even after he’d lost everything. He and his wife fled to Green Hill, Alabama, where they resided on son Hiram’s cotton plantation. He died there in 1837. His total estate reported in Alabama tallied $170.30.

David’s second son, John, stayed on in Mechanics Hill making rifles in his own business. John achieved lasting local fame in a three-way “shoot-off” before a large crowd in Carthage against fellow Moore County gunsmiths Phil Cameron and John B. McFarland. Each of the competitors claimed to make Moore County’s most accurate rifles. When the smoke cleared, all three were found to have met the bull’s-eye. The men called it a draw and each went home “feeling proud of his marksmanship, and certain that no gunsmith in the state made a more accurate shooting rifle than he did.” John continued in the business until shortly before he died in 1855, the same year a spring storm washed the Kennedy rifle mill down history’s drain. An amble today along Bear Creek’s rugged trail provides scant evidence that the area was once a beehive of activity. Aside from easily overlooked foundation stones, there is no vestige of the old factory. Capel, McSwain and Schulte knew it would take real digging to find any remnants of manufacture, but they were prepared to do just that in their visit to Bear Creek half a century ago. Over time, local residents had unearthed various metallic objects thought to have been left behind, but few of those relics had been preserved.

Working together, the three men located a small vine-tangled mound. It proved to be the mill’s discard pile. For the excited long rifle enthusiasts, the shards of buried rifle barrels, drill bits, flint hammer castings and raw silver they unearthed constituted a treasure trove as valuable as gold. These artifacts provided the insights into the Bear Creek operation.

Aficionados of David Kennedy’s rifles have launched their own Facebook site — Kennedy Rifle/Mechanics Hill. Followers post comments that run the gamut from Second Amendment discussions to providing advance notice of the Kennedy gun show and food drive recently held in Robbins in April. Historian-collectors like Capel and Asheboro’s Bill Ivey, author of North Carolina Schools of Longrifles 1765-1865, cite the historic importance of the Bear Creek gun factory as one of nine documented facilities (referred to as “schools” ) that produced the vaunted Kentucky long rifles in North Carolina.

What really excites historians and collectors are the beautiful carvings and engravings on the long rifles. Like the Kennedys, many founders of the North Carolina long rifle schools hailed from either Pennsylvania or Virginia, and their craftsmanship reflects those roots. Ornamental engraving contained on the butts of many Kennedy rifles exhibit a six-pointed star nearly indistinguishable from those found on guns made in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, where Alexander Kennedy began his career. Similarly, engravings emblazoned on the side “patchbox” (used to store cloth patches and grease) of Kennedy rifles typically reveal “flower petals” that mimic a recognized mark of Lancaster County rifles.

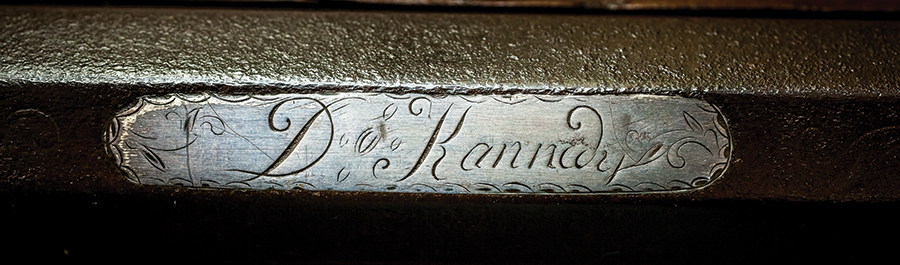

Long rifles displaying David Kennedy’s engraved initials or signature (he spelled it “Kannedy) are particularly prized. Another of the under 100 known Kennedy guns depicts a serpentine-like comet on the butt. Capel says the design was inspired by the “Great Comet of 1811,” which electrified the country for the better part of a year. In a remarkable coincidence, a Kennedy rifle owned by Capel displays the name of an English lock maker named “Robbins” on the flintlock. It was crafted more than a century before Karl Robbins’ beneficence in the community caused the town to be renamed in his honor. When asked about the market value of Kennedy rifles, savvy collectors Ivey and Capel tend to hold their cards close to their respective chests, but neither blinked at five figures as a fair starting point.

The Moore County Telephone Directory contains nearly as many entries for “Kennedy” as there are for “Jones” and more than a few are descendants of David Kennedy, including Southern Pines’ Assistant Town Manager Chris Kennedy. A gun lover and hunter, Chris had frequented Robbins many times and was generally familiar with David Kennedy’s story, but his 2015 visit to the town as a member of the Moore County Leadership Institute heightened his awareness of his ancestor’s critical role in the founding and development of the town. “It’s pretty humbling, especially in my role, to think that the Kennedys had a lot to do with development not just of Robbins, but of the whole county,” says Chris.

The rapid decline in recent decades of Robbins’ textile industry caused town leaders to grapple with how best to attract new business. One tactic has been to go “back to the future” by stressing the community’s rifle-making origins. Prominently positioned in the center of town is a historical landmark plaque recognizing the Kennedys’ “extensive gunsmithing operation” at Mechanics Hill. In 2013, the Town Council members adopted resolutions establishing the second Thursday in each April as “Mechanics Hill/Kennedy Rifle Day,” and affirming their personal sworn duty to uphold the Second Amendment.

Like the Phoenix of ancient lore, gunmaking in Robbins astonishingly rose from the ashes. Soft-spoken gun devotee and lifetime Robbins resident Joey Boswell is something of a latter day David Kennedy. After a wide-ranging career performing computer automation, engineering new product developments, and generally solving all sorts of industrial problems for various manufacturers, Boswell tired of travel to faraway destinations and being away from his family. Familiar with the design, operation and limitations of weaponry, both civilian and military, he and his wife, Martha, started their own business, War Sport Industries, LLC, in the “barn” alongside their home atop a hill in Robbins.

His first major solo project in 2008 involved finding a method to camouflage the infrared heat visible to the enemy at nighttime on the hot barrels of American soldiers’ guns after repeated firing. Boswell invented a heat-resistant device he labeled a “suppressor sock,” which did the trick. The sock became standard issue for certain Army weapons. They began producing their own armaments — the first manufactured in Robbins since the day the Kennedy factory was shuttered. After extensive research, Boswell designed what he called a low visibility operations application rifle (LVOA), which proved to be a major advancement in military weaponry.

Soon, customer demand for the LVOA increased to the point that the Boswells could no longer handle operations out of their barn and they moved War Sport to an old factory off Route 24. With operations running full tilt, two shifts, with 25 employees, War Sport had suddenly become a major Robbins employer. In 2016, the Boswells separated from War Sport and began another weapons-related enterprise in their barn. The new company is called Mechanics Hill Marketing, LLC, in homage to Boswell’s gunmaking predecessor. The Boswells and Mechanics Hill now work in partnership with Osprey Armaments in researching, developing and marketing its weapons and other related products.

“I have never had to move from Robbins to do anything I wanted to do, and I have worked overseas and everywhere,” says Boswell, who has served as a member of Robbins’ Town Council since ’09. As the catalyst to the rebirth of gunmaking in Robbins, Boswell feels a kinship with David Kennedy since — modern assembly line processes aside — the art of making guns has not changed much since Kennedy’s day. “Here we were bringing jobs to this town in the same business that started it.” PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.