Though he never swung a club until age 34, Walter J. Travis became America’s first great golfer

By Bill Case

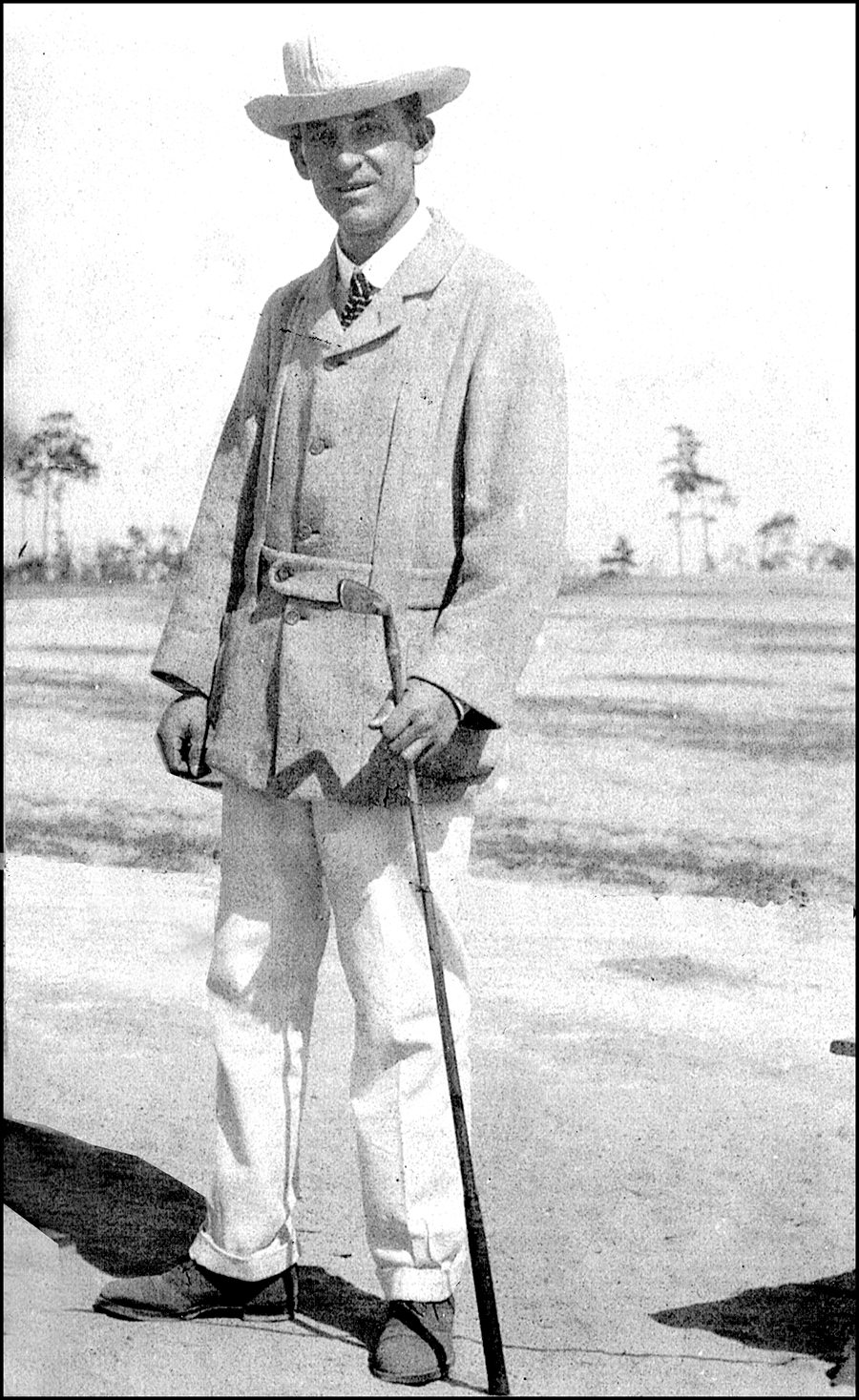

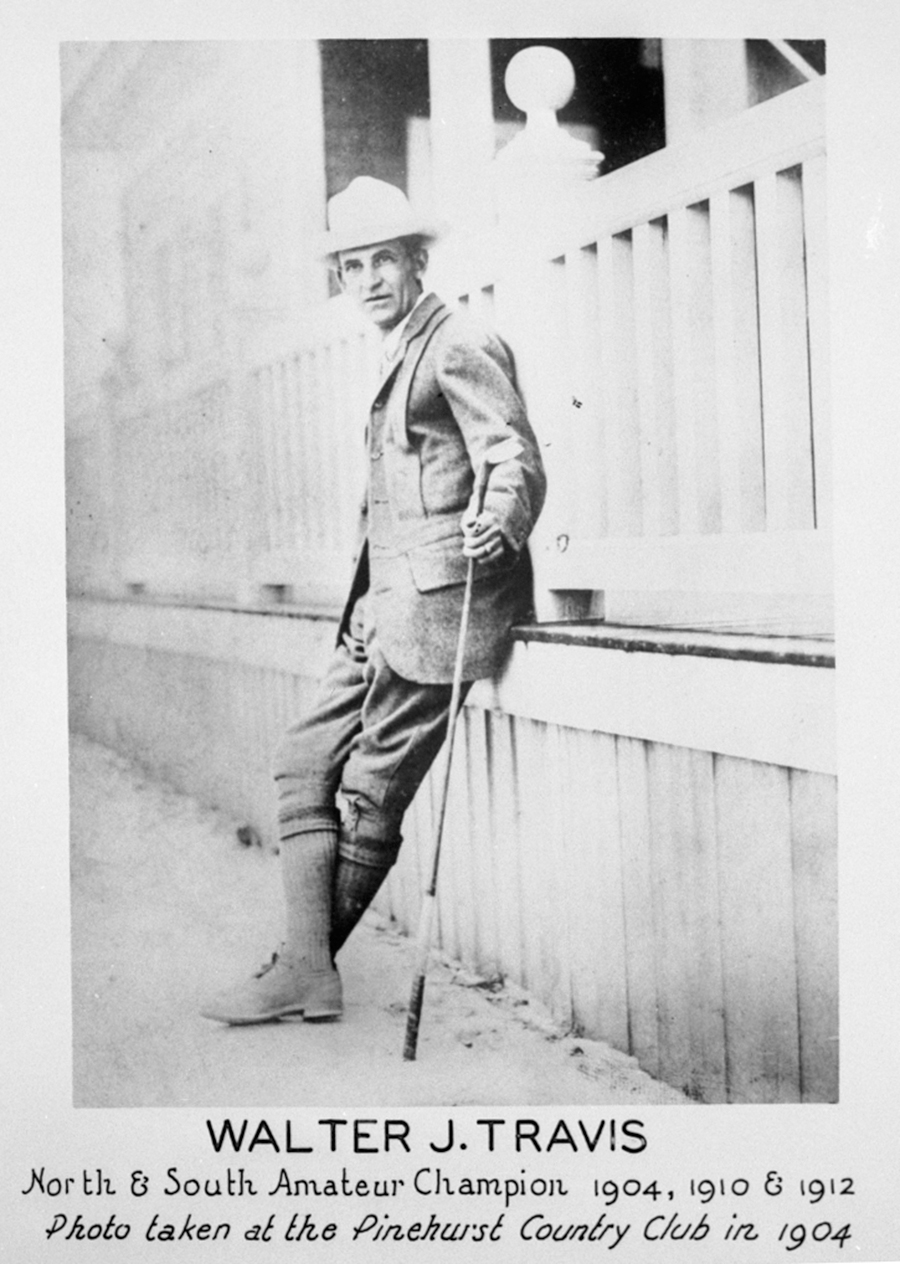

In late March 1904, Walter J. Travis checked into the Holly Inn for three weeks of golf, hoping it would culminate in winning the coveted United North and South Amateur Championship. His arrival was considered a big deal because the Australian immigrant was generally recognized to be the best golfer in the United States — amateur or pro. Called “the most conspicuous figure in the golfing world today” by the Pinehurst Outlook, the 42-year-old Travis, playing out of Garden City Golf Club on Long Island, had won three of the preceding four U.S. Amateur championships, capturing the Havemeyer trophy in 1900, ’01 and ’03.

It was a return trip for Travis, who had already won the resort’s special “Inauguration” tournament in January. “Mr. Travis was delighted with his first visit to Pinehurst,” proclaimed the Outlook, “and he returns, not only with the championship cup in his mind’s eye, but to renew pleasant associations.”

Pleasantness certainly marked his March golf. In a casual four-ball match, the homburg-hatted Travis, partnering with Charles B. Corey, carded a record score of 69 on Course No. 1, then measuring 5,408 yards. In the North and South, he posted the best medal score of all qualifiers and trounced each of his match play opponents en route to the 36-hole final against his four-ball partner, Corey. Emitting clouds of smoke from pungent black cigars, Travis played brilliantly from the outset, leaving his erstwhile partner six holes in arrears after the morning round. Following lunch, he coasted to an 8 and 7 championship victory.

While the North and South was a valued title, Travis had his eye on a greater prize: the British Amateur championship in May at Royal St. George’s Golf Club in Sandwich, England. No American had ever accomplished anything noteworthy in the event. It seemed a pipedream for Travis to think he could stand toe-to-toe with British stars like John Ball and Harold Hilton, considered far superior players to the best in America.

C.B. MacDonald, the renowned course architect and 1896 U.S. amateur champion, thought otherwise, pointing out that Travis was four strokes better over 36 holes than any other American. If Travis (already approaching the life expectancy of the average American male in the first decade of the 20th century) could withstand the rigors of the ocean voyage and change in climate, reasoned MacDonald, he would likely give a good account of himself.

Most golf aficionados “on the other side of the pond” scoffed at the idea. On his previous trip to Great Britain in 1901, Hilton had beaten him easily. Short of stature and weighing less than 140 pounds, Travis was admittedly not a long hitter, a problem because Royal St. George’s was tailor-made for powerful drivers. Could he carry the venue’s vast bunkers like the aptly named Sahara and Himalayas? Most of all, British golf cognoscenti doubted that anyone who hadn’t taken up the game until the age of 34 — and looked even older than his years — could hope to be a true championship player.

Nothing about Travis’ hardscrabble early life suggested that he would become a celebrated sportsman. Born in Maldon, Australia, in 1862, he was the fourth child of Charles and Susan Travis. A native Englishman, Charles had emigrated Down Under in 1852, seeking to capitalize on the country’s gold rush. Though he failed to amass riches, he did land a respected position as a mining engineer. Tragedy struck in 1880, when Charles was killed in a mining accident, leaving wife Susan and their seven children in dire circumstances. When Walter’s older brother perished the following year, the burden of supporting the family fell primarily on him. After it became apparent that work in a grocery store and sheepherding on the side wouldn’t support a family, he took a position with the hardware merchants McLean Brothers in Melbourne. He rose rapidly up the company ranks and, when McLean Brothers decided to open a New York City branch in 1885, 23-year-old Travis agreed to head up the satellite office.

Travis diligently attended to McLean Brothers’ affairs. Though a bit standoffish, he spent convivial evenings with his mates, drinking whiskey, shooting billiards and playing poker. His interests expanded to include bicycle racing, tennis and bird hunting. But his most intense outside interest was courting the comely and spirited Anne Bent.

“For a man seen as dour, abrupt and serious for much of his public life, Travis was effusive, romantic and smitten while courting Anne,” says Bob Labbance, author of The Old Man, a biography of Travis. “He could write six pages about nothing more than how much he loved her, missed her, and couldn’t possibly wait until they were together again.” Anne would play hard to get, but Walter’s persistence won her over, and the couple married on Jan. 9, 1890, settling in Flushing, New York, and parenting a son and daughter.

In 1895, McLean Brothers sent Travis to London on temporary assignment. While there, he learned that several friends back in Flushing intended to become members of a new golf club.

At first, Travis rejected any notion of joining them. He would write that “the game made no appeal to me. I am free to confess that I had mild contempt for it.” But, not wanting to be left out of the mix, Travis grudgingly purchased a set of clubs, “and with anything but pride, brought them over on my return.”

He joined the Oakland Golf Club in the fall of 1896 and embarked on his improbable golf journey. Just a month after hitting his first ball, he won a handicap competition. The next month he finished second in a scratch competition. He was hooked. The golf convert assiduously studied golf instructional books authored by British golf greats Willie Park and Horace Hutchinson. Together with “an enormous amount of experimentation,” it culminated in Travis gaining a well-grooved swing that invariably resulted in an exquisitely controlled hook.

The following summer, Travis, now down to a 7 handicap, entered numerous medal play events, acquitting himself with distinction. He won an event at the Meadow Brook Hunt Club after riding his bicycle to the first tee to submit his entry for the competition. That triumph was followed by a victory in Oakland’s club championship. He won his first foray into a match play event and lost in the finals of another. The press took notice of what was rapidly becoming a Cinderella story. One headline read, “Travis a Surprise — Almost an Unknown Man.”

More titles followed in the summer of 1898. Encouraged, he entered the U.S. Amateur that September. Incredibly, the player of less than two years’ experience made the semifinals. Dogged by poor putting, Travis was beaten decisively in the penultimate match by Findlay Douglas, a player who would become a perennial foe. The two met for a second time in the semis of the 1899 Amateur championship, and Douglas would prevail once again 2 and 1. It was clear, however, that Walter’s golfing skill was fast approaching that of his fiercest rival.

Prior to the 1899 Amateur, Travis was approached by a friend, James Taylor, to see if he would be interested in working with architect John Duncan Dunn in designing a new course, Ekwanok Golf Club, in Manchester, Vermont. America’s early courses often featured flat, square-shaped greens with bunkers, chocolate drop mounds, and hazards sprinkled across the entire width of fairways. Travis believed such hindrances should be placed at the sides of fairways so as not to penalize straight hitting, and that greens should have varying shapes and undulations. Sensing he could design a layout with more challenging features than most he had encountered, he accepted the invitation.

Travis spent much of September and October of 1899 in Vermont, immersed in Ekwanok’s construction. His detail-oriented mind and organizational skills proved well-suited for the multi-faceted task of designing and building a golf course, and he relished the work. The finished course, recognized as excellent in all regards, helped establish Travis as an architect of stature.

Early in 1900, the Travis family moved from Flushing to a house in Garden City, where he joined the Garden City Golf Club, a short walk from home. He was immediately appointed club captain and chairman of the green committee. As such, he made numerous design changes which toughened the course. His choice of Garden City proved especially timely because the club was hosting the 1900 U.S. Amateur. By the time the championship began, Travis knew every blade of grass on the course’s 6,070-yard layout. Medalist in the 36-hole qualifier, Travis blitzed through four opponents to the final where, once again, he confronted Findlay Douglas.

Despite having lost twice before to Douglas in the championship, Travis exhibited fearless confidence in this encounter. “Always be on the aggressive,” Travis would write in his autobiography. “(Be) quite sure of yourself and never give an opponent the psychological advantage of imagining you are the least afraid of him.”

Travis more than made up for his relative lack of length with stellar pitch shots and sand play. “Eight times Travis got into the sand hazards or in the long grass,” reported Golf magazine, “and each time with his iron he laid himself dead to the hole.” He led Douglas by three holes after the morning round. During the afternoon, Douglas made inroads on the lead, and was only 1 down coming down the 18th. By then a torrential downpour had flooded the course, and the home green was transformed into a virtual lake. Still, play continued.

After successfully splashing his approach onto the waterlogged green, Travis needed to get down in two strokes for the championship. He concluded, however, that rolling a putt with a mostly submerged ball was impossible. Instead, he executed a brilliant flop shot that left his ball inches from the hole, clinching the match. Just three years and nine months after his first strike of a golf ball, Travis had won the national amateur and vanquished his nemesis Douglas. He repeated as amateur champion in 1901 and won the title a third time in 1903. He also finished runner-up to Scotland’s Laurie Auchterlonie in the 1902 U.S. Open, also contested at Garden City.

Thus, while the Brits airily belittled his chances of winning the 1904 British Amateur, Travis was quietly optimistic, having just won the North and South in Pinehurst. Four Garden City club members accompanied him to Great Britain. The entourage referred to themselves as Walter’s “board of strategy.” The jocular Simeon Ford was among them. Ford would cheekily recall Travis’ debilitating seasickness during the ocean voyage. “He (Travis) spent the major portion of the time leaning over the rail, perfecting his follow through, and casting his bread upon the water.”

Once on shore, Travis’ queasy stomach became the least of his concerns. His good form vanished in wretched practice rounds at St. Andrews and Prestwick. He felt completely lost. Fortunately, his game markedly improved once he arrived at Royal St. George’s.

“From the first ball I struck, I knew I was on the road to recovery,” he wrote.

Travis’ putting had been particularly atrocious. On the eve of his opening match, an alarmed board of strategy cohort lent his personal putter to Travis. The “Schenectady” was a center-shafted mallet putter quite unlike the paper-thin blades then universally used. The loaner proved to be a godsend. In his final practice round, Travis suddenly began holing putts from outlandish lengths.

His golf was turning around, but Travis was growing increasingly resentful of how the Brits were treating him and his friends. Presumably due to oversight, no rooms had been reserved for them at the hotel where the other players were housed. The club failed to provide Travis a locker; he was relegated to changing clothes in a public hallway. The better players declined playing with him in practice rounds. The caddie assigned to Travis was beyond incompetent, “a natural-born idiot, and cross-eyed at that,” he groused. Officials refused Travis’ request for a replacement. Unlike the top British players, he was not afforded a first-round bye. British spectators cheered his misses. For the seething American, these incidents provided what would have been bulletin board material, had such a thing existed. The slights spurred Travis on, as he later acknowledged metaphorically. “A reasonable number of fleas is good for a dog,” he mused. “It keeps him from forgetting he is a dog.”

In The Story of American Golf, Herbert Warren Wind described the unusual methods the board of strategy employed each evening to prepare Travis for the following day’s matches. “They played cribbage with him and fed him large portions of stout,” while lauding the talents of prospective opponents. Goaded and fortified, a steely Travis stormed to the semifinal, leaving four opponents in his wake. His deadly accuracy with the Schenectady astounded everyone. Fears that his shortish drives would not surmount Royal St. George’s cavernous bunkers proved unfounded — but just barely. Time and again, he would carry the sand by about a yard, frustrating his opponents and those touting British superiority.

In his semifinal match, Travis confronted none other than Horace Hutchinson, the man whose instructional book he had devoured. With spectators openly rooting against the upstart American, Travis fought his way to the championship match, defeating his “teacher” 4 and 2. In the final, he faced Ted Blackwell, regarded as one of the game’s longest hitters. But Travis assumed control of the match from the outset.

“I had a comfortable feeling all through,’ he would recall, “and after the first few holes had been played, I felt certain of winning.” His black cigar smoke permeating the crisp air, Travis coasted to a 4 and 3 victory. The Scotsman described him as “coolness personified.”

The triumph marked the first glimpse of the coming American hegemony in golf. “No international sporting event for a long time has created the widespread interest that has been excited by Travis’ victory. Travis may now justly be called the amateur golf champion of the world,” claimed The New York Times.

Feted as a conquering hero upon his return to New York, Travis’ celebrity status opened the door to lucrative opportunities including new course design assignments. Having authored his own instruction book, Practical Golf, in 1901, Travis was widely sought as a contributing writer by golf-related magazines and penned pieces on topics ranging from proper upkeep of greens to the art of putting. In 1908, he became the owner and editor of a new magazine, The American Golfer, a publication that he promised would promote “the best traditions of the Royal and Ancient game.” Among the backers of the venture was Pinehurst mogul Leonard Tufts.

Able to mostly support himself from golf-related activities, Travis resigned his post with McLean Brothers. There were occasional mutterings that his receipt of income from golf architecture and writing ought to disqualify him from amateur competitions, but USGA rules were not specific on the matter, and most concluded that Travis wasn’t doing anything wrong.

By the time Travis took the reins of The American Golfer, the 46-year-old had already been tagged with the moniker “the old man.” Due perhaps to advancing age or focus on the magazine, the single-minded competitive drive that had characterized his golf began to wane. His days of winning national titles were behind him as talented young stars like Chick Evans and Jerry Travers rose to prominence.

Still, Travis remained a threat to win any tournament he entered throughout his 40s. He relished playing, particularly in Pinehurst, which from 1904 until 1915 served as a second home for him from January to April. Travis would typically arrive after Christmas and stay at either the Holly or The Carolina through Valentine’s Day, then migrate to Palm Beach for a month before returning to Pinehurst in mid-March. It would be Travis’ headquarters until the conclusion of the United North and South Championship in mid-April. In all, he won that coveted event three times, following up his 1904 title with victories in 1910 and 1912 — at age 50.

Travis participated in a number of lesser Pinehurst tournaments, winning more than his share. His trophies included the Mid-Winter, St. Valentine’s Day, and Spring tournaments. The competition he faced was stiff, and he lost more than he won. He played numerous four-ball exhibition matches, many involving the Ross brothers, Donald and Alex. Hundreds of resort guests eager to see him in action attended. His conspicuous presence undeniably enhanced Pinehurst’s growing reputation and, as editor of The American Golfer, he arranged for extensive coverage of Pinehurst golf doings throughout its season.

Travis’ most important contribution to Pinehurst golf, however, may have been his role in transforming easy and bunker-free Course No. 2 into a venerated championship venue, maintaining that he was the person who persuaded the resort’s owner to redesign the course. “For several years, I had been at Mr. Tufts, the proprietor, to make this (No. 2) an exacting test,” wrote Travis in his 1920 piece for The American Golfer. “Finally, in 1906, I won him around to my way of thinking . . . ”

He further claimed that Tufts gave him the job of making the required changes to No. 2. “He gave me carte blanche to go ahead,” he wrote. Travis maintained that he was responsible for bringing Donald Ross onto the project. “I knew the changes I had in mind would result in a big uproar at the start, and I didn’t feel like shouldering the whole responsibility. So I suggested that Donald Ross and I should go over the course together and, without conferring, each propose a separate plan. I knew what the result would be.”

While stopping short of taking credit for No. 2’s redesign, Travis did say that Ross adopted virtually all of his suggestions, and that the Scottish transplant “was merely an echo of my own views regarding golf course architecture.”

While it’s fair to speculate whether Travis could have been exaggerating his role given his substantial ego — and the fact that he made these boasts 14 years after the events in question — it’s also reasonable to assume that in redesigning No. 2, Ross would have listened to anything the country’s leading golf figure (and fellow architect) had to say. And Ross never publicly contradicted Travis’ account. Whatever the extent of his involvement, it would seem Travis deserves, at minimum, some credit for contributing to the Ross masterpiece.

While normally restrained in his emotions, Travis effusively expressed his affinity for Pinehurst in remarks at a 1911 banquet at the Holly Inn. Travis said Pinehurst had come to have a “very warm place” in his heart and that “what St. Andrews is to golf on the other side, Pinehurst is to the game in America.”

The Old Man competed in Pinehurst events well into his sixth decade and, at age 53, won the resort’s March 1915 Spring Tournament. “Surely golfers may come and go,” reflected an admiring piece in the Outlook, “but Travis goes on forever! Straight down the alley, straight for the pin, straight for the cup.” But age was taking a toll on his already insubstantial drives, something that didn’t escape the notice of frequent playing companion Ross. “I watched him get crabbier and crabbier the older he got,” confided Pinehurst’s masterful architect. “He was always a great putter . . . but his long shots became shorter and shorter and he couldn’t reconcile himself to his loss of distance.”

Not long after that final Pinehurst victory, Travis decided to quit playing major events. While the decline in his play surely factored into the decision, the USGA was also on the threshold of adopting a rule that would result in golf course architects losing their amateur status. Travis was looking forward to expanding his course design business and, realizing it might be problematic, retreated from competitive efforts altogether. He elected to make the 1915 Metropolitan Amateur at The Apawamis Club in Rye, New York, his last important event. He shocked everybody with a series of impressive victories in the preliminary matches, even edging the formidable Travers, en route to the final where he faced John G. Anderson.

Travis’ supporters questioned whether he could still summon the necessary stamina and concentration for a 36-hole match, and he did flag down the stretch, blowing a 3-up lead over Anderson in the final nine holes. The match stood dead even as Travis staggered to the final green. He needed two putts from 40 feet to send the contest to extra holes. Instead, he electrified onlookers by holing the mammoth putt for the championship, his fourth Met title, and a spectacular farewell to big time golf for “The Old Man.”

Travis’ architectural services were increasingly in demand. Over his lifetime, Travis would design or remodel at least 50 courses, many now regarded as timeless classics. His notable projects include courses at Yahnudasis Country Club (Troy, N.Y.); Westchester Country Club (Rye, N.Y.); Equinox Golf Links (Vermont); Jekyll Island Golf Club (Georgia); Hollywood Golf Club (Deal, N.J.); Country Club of Scranton (Pa.); and modifications at Garden City. He designed courses until the end of his life in 1927, and today the Walter Travis Society continues to celebrate his accomplishments.

In 1979 he was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame. Given his late start, it is difficult to conceive how Travis managed to pack so much achievement into such a short period of time. Still, it was never quite enough. “Full as my cup has been,” Travis reflected, “I shall never cease to regret the many prior years which were wasted.” PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.