The rise and fall of Moore County’s plank roads

By Bill Case • Images courtesy of the State Archives North Carolina

It is hard to envision just how remote and isolated the Sandhills were in the 1840s. Pinehurst, Southern Pines and Aberdeen were decades away from coming into being. Infrastructure was virtually nonexistent in this sparsely populated area. With only rutty, often impassable dirt trails to travel upon, the area’s scattered farmers and plantation owners — mostly of Scottish descent — found it inordinately difficult to ship harvested products like turpentine, naval stores, fruit and tobacco much beyond the Moore County line. The same predicament confronted settlers throughout the state’s interior all the way to the Piedmont. Merchants in the Eastern market towns were similarly exasperated with the perpetual challenges of sending supplies in the opposite direction.

Bustling Fayetteville emerged as a transportation hub of importance. Commodities coming from the frontier could be barged from the city’s wharf on the Cape Fear River down to the coast at Wilmington. From that seaport, oceangoing vessels could move goods to destinations up and down the Eastern Seaboard and as far away as Europe. But the maddening obstacles to transporting merchandise (and people) from the west to Fayetteville were forestalling the development of that city and the state’s economy.

A better transportation model had to be found, and a band of Fayetteville promoters took the lead in exploring alternatives. The building of a new railroad was considered, and a prospective train route west was surveyed. But the scheme was ultimately abandoned because of (according to one disenchanted proponent) “the poverty of the country.” A railroad would not enter Fayetteville until 1858.

More intriguing was the concept of wooden plank roads. They had proved popular and cost-effective in Canada and areas of New York state. Compared to what was needed to build a railroad, construction materials were readily available and inexpensive. No iron or steel was required, just wooden planks 8 feet long and 8 inches wide laid horizontally across long heart pine sills and covered by a thin layer of sand. The necessary lumber could often be found in the woods right beside the construction site. The roads were “single track,” just wide enough for a single wagon, but users were able to pull to the side on parallel dirt paths so that oncoming wagons could pass.

The most appealing aspect of “mudless highways” was the time saved in transporting goods or stagecoach passengers. The distance that took a wagon four days over the ancient dirt or sand paths could be traveled in 18 hours on a plank road. According to one observer, the increased efficiency on planks was the result of “the diminution of friction by which a horse was able to draw two or three times as great a load as he could on an ordinary road.”

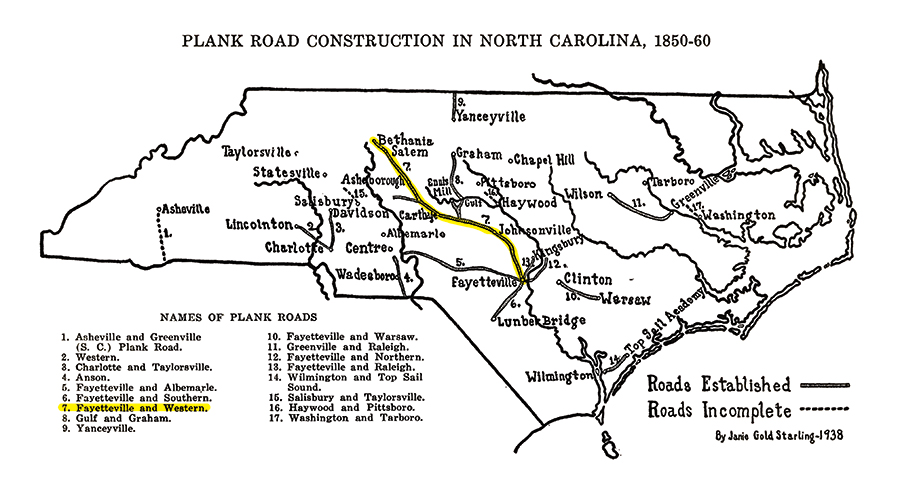

A movement to build plank roads from Fayetteville into the state’s interior rapidly gained steam during the 1840s, led by Gov. William Graham, who believed that poor roadways had placed North Carolina under “greater disadvantages than any state in the union.” He convinced the state legislature to grant charters to those entrepreneurs seeking to build and operate plank road companies. Five such charters were granted for roads that fanned out from Fayetteville like bicycle spokes to various westerly destinations. The state of North Carolina even purchased stock in several of them.

Not surprisingly, there was political controversy regarding whether North Carolina should be dispensing taxpayer funds to support these private ventures. The state’s entrepreneurs and merchants (generally associated with the Whig Party) overwhelmingly approved of the public investment. Not only would their businesses benefit, the value of their real estate holdings alongside any new road would also potentially skyrocket. The Fayetteville Observer reported that the plotting of a plank road through one vast tract caused the land’s value to shoot up from 11 cents per acre to $2.

Many small farmers, primarily Democrats, suspected that the state’s partnership with the companies would inevitably lead to roads not being routed with the best interests of the public (and that of small farmers) in mind. There was suspicion that the landed gentry would be tempted to make payoffs to ensure roads were routed next to, or through, their properties. And farmers objected to the legislature’s broad grant of eminent domain powers to plank road companies.

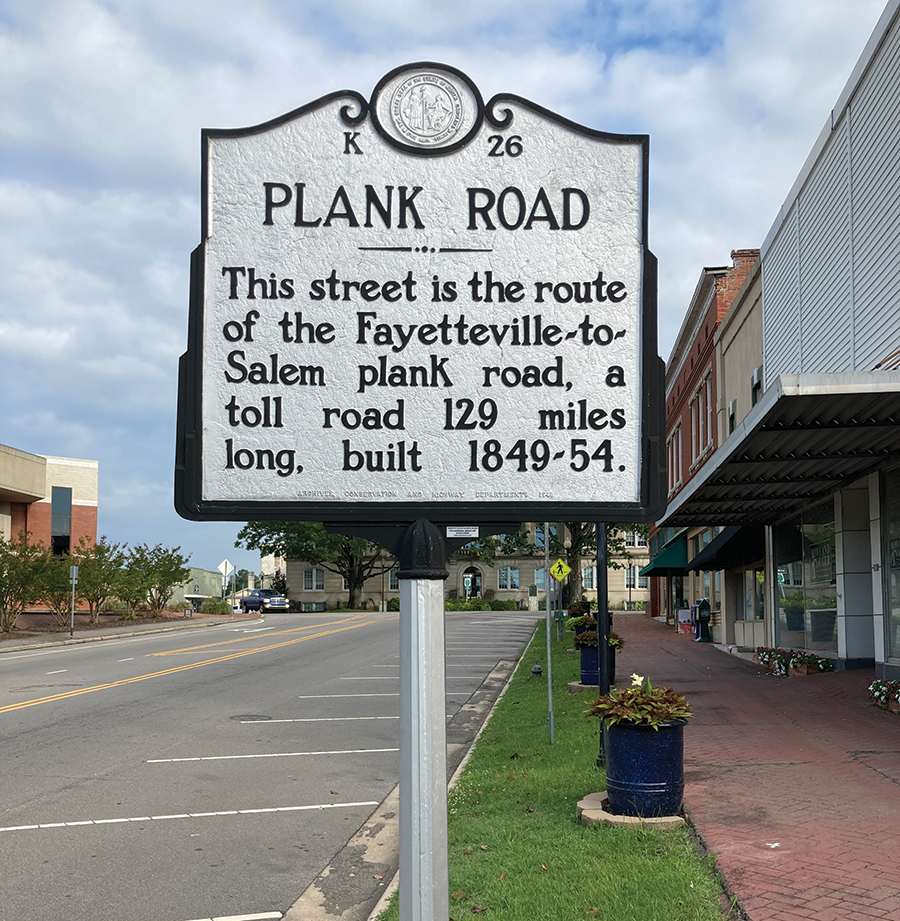

The most ambitious undertaking was that of the Fayetteville and Western Plank Road Company (ye olde F&W), which contemplated building the longest wooden road in history (129 miles) from Fayetteville to Salem (now Winston-Salem). Billed by its boosters as a latter day Appian Way, the proposed road sparked interest in Moore County as plans called for it to pass through Carthage. More westerly communities along the wooden highway’s intended path included Seagrove, Asheboro and the then tiny settlement of High Point. Much of the proposed route had been trailblazed by Daniel Boone in the 1760s.

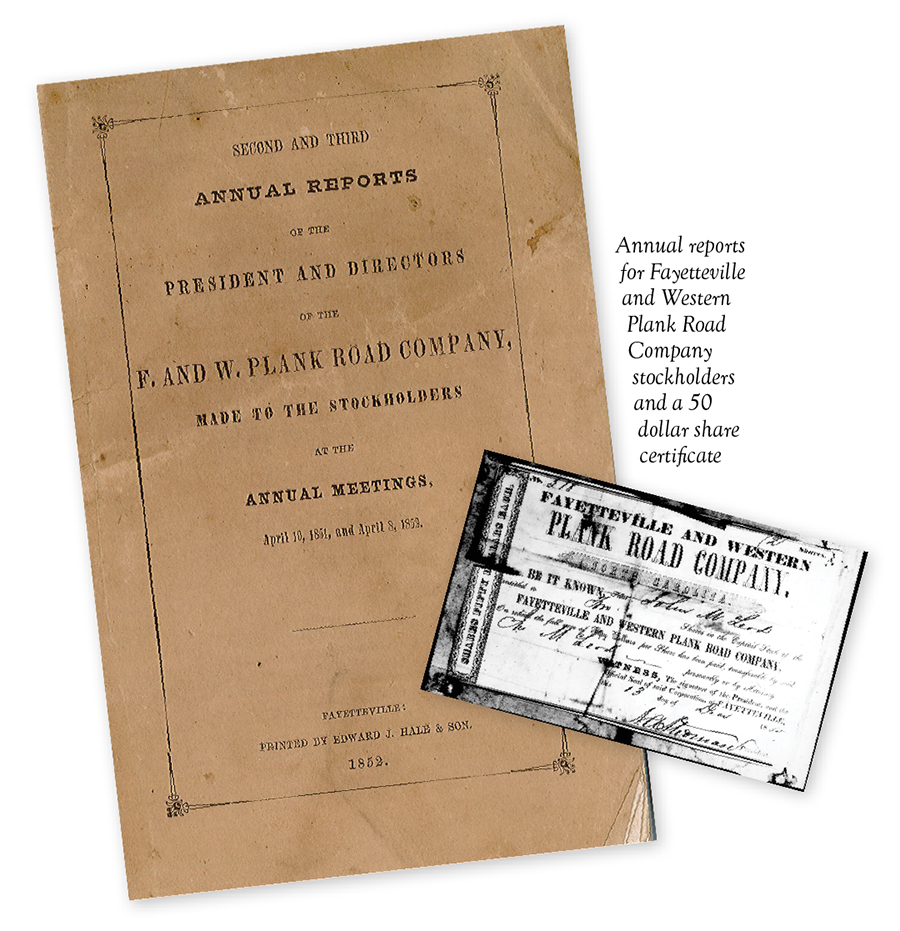

In the course of a three-day public meeting held in Fayetteville on April 11, 1849, F&W promoters successfully solicited $80,000 in stock subscriptions from private investors. The state of North Carolina acquired controlling interest in the company by tendering its own subscription in the amount of $120,000. The shareholders elected a board of directors and hired Edward L. Winslow as F&W’s president at the munificent annual salary of $500 plus traveling expenses.

Revenue to operate the proposed road was to be generated by collecting payments at tollhouses — manned by keepers, naturally, since E-ZPass was a few years off — placed approximately 11 miles apart. Fares were set at one-half cent per mile for a horseback rider, one cent for a carriage pulled by one horse, two cents for a team of two horses, and four cents for a six-horse team.

Construction of plank roads involved an arduous process as the underlying surfaces had to be carefully graded for proper drainage. On a productive day, a team of 15 workers could lay 650 feet of planks at an estimated cost of $1,300 per mile. North Carolina’s wooden roads were mostly built by private individuals subcontracted by the chartered companies. According to historian Robert B. Starling, many of these contractors accepted company stock in partial payment for their services, a shrewd move since savvy investors considered plank roads a can’t-miss proposition. The editor of Salisbury’s newspaper, the Carolina Watchman, was among the cheerleaders, writing, “There is scarcely a man of intelligence but believes the stock [in the F&W] would pay a handsome dividend.”

Hordes of opportunists endeavored to capitalize on the perceived bonanza by applying for authorization to build other plank roads. A majority of those applications involved construction of spur extensions stemming off the five westbound roads from Fayetteville, including the F&W. The legislature liberally green-lighted charters (84 in all) with the nonchalance of a grocery store handing out potato chip coupons.

In 1850, the F&W commenced the construction of the initial section of its plank road running from Fayetteville’s Market House to the Little River. That stretch was completed and placed under toll by April of that year. According to Starling, the remaining sections, including the one running through northernmost Moore County, were awarded by contract.

When the contract for the construction of the section of road around Cameron was awarded, the prospects of successful bidder Maj. Dugald McDugald seemed especially rosy. McDugald was in a position to profit from the venture in several ways. Not only would the 47-year-old be paid handsomely for building the road, it would pass through McDugald’s land just north of Cameron, increasing the value of his 4,000-acre spread exponentially. The wooden highway would also provide superior transportation to Fayetteville for the turpentine and naval stores produced from the tens of thousands of pines on McDugald’s plantation. He also intended to build a large hotel adjacent to the plank road at a point where it straddled the Moore and Lee County lines (in the vicinity of Page Store Road today).

Dugald’s father, Col. Archibald McDugald, had been a figure of note in North Carolina during the Revolutionary War. After emigrating from the Scottish Highlands in 1767, Archibald chose to fight with Loyalist forces when hostilities erupted between the Crown and the Patriots. Archibald’s association with the losing side ultimately caused him numerous travails. Captured by the Patriots in 1779 while journeying south to join Loyalist forces in Savannah, Georgia, he was held on a prison ship in Charleston Harbor for nearly a year. After his release in an exchange of prisoners, he joined the Royal North Carolina Regiment and was subsequently appointed to the rank of colonel in the Loyal Militia. The elder McDugald was a lead officer in the astonishing 1781 Hillsboro raid in which Loyalist militia captured Patriot Gov. Thomas Burke.

After the close of the war, the state confiscated 740 acres of McDugald’s land. Like many Loyalists, he settled for a time in Nova Scotia, then later sailed to England, where he spent three years successfully petitioning the Crown for a pension. Archibald returned to Moore County around 1794 and married Rebecca Buie. The couple parented four sons and two daughters. Archibald’s subsequent financial recovery enabled him to reinvest in northern Moore County real estate, and Dugald inherited much of the land after Archibald’s death in 1835.

As was the case with virtually all Southern plantation owners in the antebellum period, Dugald McDugald owned numerous slaves. But with his farming operation, the harvesting of turpentine, building of the hotel, and the plank road under construction, he needed even more manpower. McDugald asked his wealthy neighbors whether they would agree to let him “borrow” their slaves to perform the labor involved in constructing the road. Records are vague, but it appears he rented 15 slaves from Kenneth Murchison and many more “upcountry” from a Mr. Alston.

As Starling puts it, McDugald was “playing a game of chance.” He, his brother Daniel, and sisters Peggy and Polly were required to give their bond promising safe return of the slaves. After the work began, disaster struck. Typhoid fever broke out among the crew, and the deadly disease rapidly overwhelmed the project. At least 12 of Murchison’s 15 slaves died. The total number of deaths from the devastating ordeal is unknown. The ill-fated workers are believed buried in unmarked graves on the Moore County side of the plank road, a forlorn and untended testament to the suffering endured by African-Americans in building the South’s infrastructure.

The debacle financially ruined McDugald. To make good on his bond to the slaves’ owners, he was forced to liquidate all but 200 acres of his plantation. Construction of the unfinished hotel was abandoned. The locals referred to the misbegotten — now long gone — structure as “McDugald’s Folly.”

Col. Alexander Murchison completed the section of the F&W road up to Carthage. In a furious dash to the finish, Murchison operated five steam sawmills day and night. The F&W also built a tributary spur from the main plank road north to the small settlement of Gulf and south to a point immediately west of Cameron. Today, South Plank Road follows the path of this old spur.

By January 1853, the plank road neared Salem. However, leaders of the community’s powerful Moravian Church balked at locating the road within the town due to concerns that wagons and stagecoaches creaking over the wooden planks would disturb religious services. Eventually, the F&W’s terminus was moved 7 miles from Salem to Bethania. On April 13, 1854, the F&W stockholders were told that the road was finished.

The long-awaited linking of the Piedmont region with Fayetteville and its river access to the coast brought a sense of excitement to the previously isolated hamlets. “The arrival of the stagecoaches was announced by the loud blowing of a bugle,” wrote historian J. H. Monger, “and crowds often gathered in the villages to see the stagecoaches arrive.”

Initially, the F&W seemed on the threshold of becoming an Amazon-like blockbuster business. In 1853, it earned net income of over $17,000. The following year that net increased more than 60 percent to $27,419,77! Loftier future profits were predicted.

It wasn’t to be. An array of intractable difficulties beset the F&W and the other plank road ventures. Based on the experience of Canadian plank roads, it was presumed that the F&W’s wooden planks would not require replacement for 10 years. Unfortunately, the lifespan was less than half of that in North Carolina’s heat and humidity. Winslow’s 1853-54 report to the shareholders provided sobering guidance. “The expenses of repair and replacing planks on the road, bridges, and culverts, will be heavy, I fear, in the coming year,” wrote the president.

Despite the fact that Winslow’s tenure had resulted in net profits, the state, with controlling interest in the F&W, decided not to renew his contract in 1854. The new president was quickly confronted with even greater threats to the bottom line. Revenues were steadily declining — nefarious users of the road had found ways to bypass the tollgates. The cheating became so rampant that the company hired traveling toll collectors to track down the miscreants.

The 1850s also marked extensive railroad expansion throughout North Carolina, and an increasing number of the state’s farmers found it to their advantage to use them rather than the plank roads to transport their products. To make matters worse, one of the few American financial catastrophes significant enough to have its own name occurred. The Panic of 1857 diminished economic activity, dried up credit, and made paupers of farmers and merchants alike. The F&W’s report to shareholders that year noted, “The great diminishment of toll is owing to two causes — the short crops and the completion of the North Carolina Railroad.” The cost of repairs ($20,388.72) substantially exceeded the tolls collected ($15,966.69).

In 1858, F&W president Jonathan Worth tried his best to put a positive spin on the company’s increasingly dire situation, professing his belief that income from operations would not decrease any further while cautioning that “no dividend, however, can be paid for some time to come, if the road is kept in reasonable repair.” The company’s problems mirrored those of the other chartered plank road companies, many of which never built any roadway at all. Only 500 miles of plank roads were ultimately constructed in North Carolina, and the F&W built a quarter of the total.

Plank roads were on life support by the end of the decade, and the turmoil of the Civil War pushed the entire enterprise over the cliff. Business activity on the roads virtually ceased. The planks soon deteriorated into total disrepair. By 1862, the state had authorized the F&W to abandon the road and sell the assets.

In vogue about the same length of time as disco in the 1970s, these “farmers’ roads” played a critical role in opening up the entirety of the state to commerce and cemented Fayetteville’s position as an important transportation hub. High Point was virtually non-existent before F&W’s road came through, and the same can be said for Cameron. The road also favorably impacted Carthage. Once the plank road reached that community in 1850, a new business was formed to meet the increased demand for carriages. That operation was the forerunner to the iconic Tyson and Jones Buggy Company, which manufactured buggies in Carthage until 1925.

The old wooden highways may be no more, but the creaking of wagon wheels across the planks still echoes and the cost, unmarked, still lingers. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.