The legacy of Jimtown

By Bill Fields • Photographs provided by the Moore County Historical Association

Opening photo: Our Lady of Victory School in 1948

Nearly a century ago, a man wrote a letter to the editor of The Moore County News. He was proud of his community, proud of his home, plain proud. The newspaper had included in the previous week’s edition a positive story about “Jimtown,” the African American neighborhood on the sunset side of the tracks in Southern Pines.

“Of course Jimtown is a very peculiar name, and West Southern Pines sounds much better, but Jimtown is alright. We are delighted over your discussion of Jimtown and what we are doing here. We are building our homes and repairing the old ones. … I am building me a home here in Jimtown. When you pass through here look for my beautiful home on Connecticut Avenue, a space of 150×161 feet, overlooking Knollwood.

“It has always been said that a city sitting upon a hill cannot be hidden. So there is too much going on here in Jimtown to be hidden. Of course Jimtown is not a city but you bet your life it sits upon a hill. Jimtown is making wonderful progress this year. We can’t keep up with you white people with money, but our outlook is fine. We know that we can’t go over the top, but we are going to the top.”

A Jimtown Citizen

STEPHEN J. SANDERS

When Sanders wrote those words of pride and hope, it had been only 23 years since the Wilmington coup of 1898 just 135 miles to the east, a violent overthrow of a legitimately elected government, massacre of African Americans and the destruction of their community. The Ku Klux Klan was poised for a resurgence. Racial segregation in the Jim Crow South was decades from its reckoning.

“That event (Wilmington 1898) ripples out for a long time,” says Dr. Katherine Charron, associate professor of history at North Carolina State University. “In terms of the terror, in how Black people had to readjust to disenfranchisement. The Black community probably turns more inward because of disenfranchisement and violence. It is doing institution building and self-governance.”

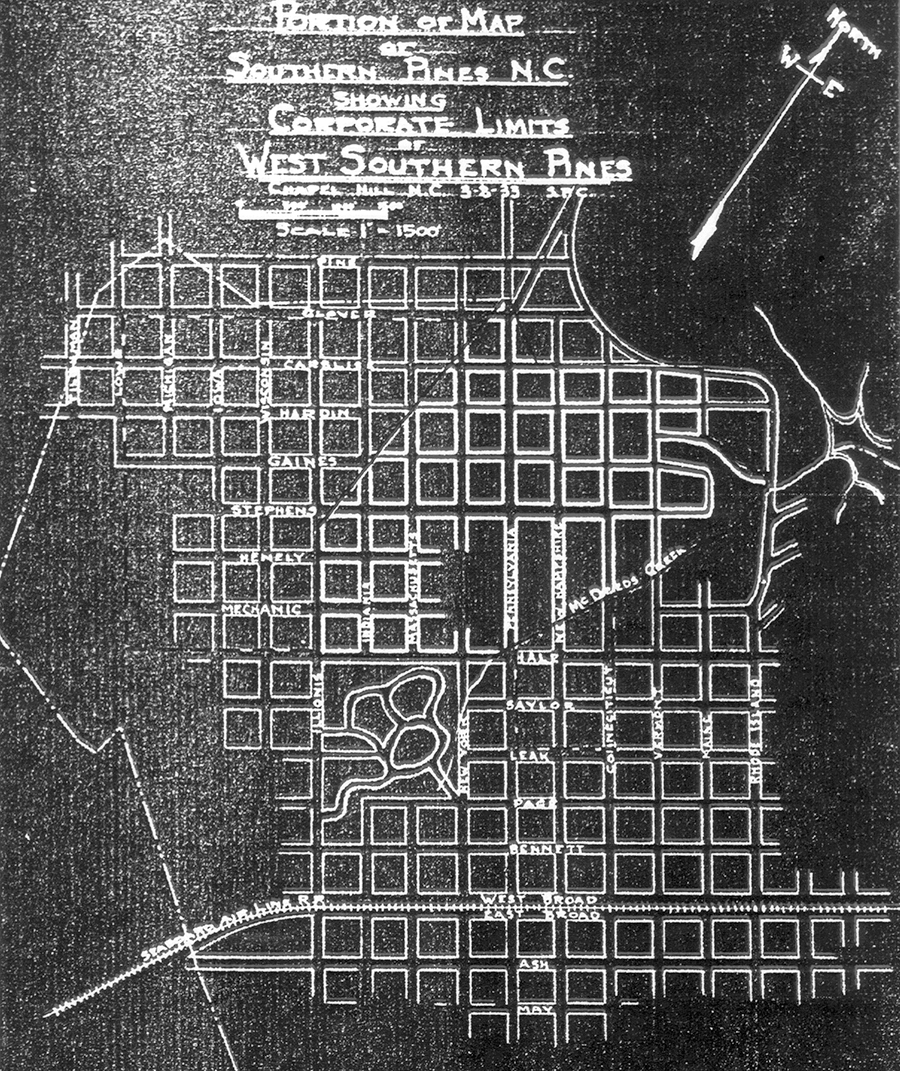

For African Americans in Southern Pines, community control took a formal turn in 1923 when Jimtown was incorporated as West Southern Pines, a rare development in the South at that time. The town remained a separate entity until 1931, when it was annexed by Southern Pines.

Before, during and after its eight-year period as a separate town in segregated times, West Southern Pines was a community populated with citizens who shared Stephen Sanders’ pride despite the injustice and hardship they faced.

“All of our needs were met and most of our wants,” says Dorothy Brower, a 1969 graduate of West Southern Pines High School, the last class prior to the opening of integrated and consolidated Pinecrest High School that fall. “We grew up with the self-confidence that we can do, that we will do. Our parents never told us we were not as good as white folks. And we had the support of everybody in the community, everybody in the schools. We didn’t have to look outside our homes and communities for our heroes.”

Brower’s father, Hosea, was one such role model. He contracted polio as a baby, which paralyzed his left leg and forced him to use crutches the rest of his life. But he didn’t let his disability govern his ambition. As a young man, he wrote President Franklin Roosevelt a letter asking for assistance in vocational training. Brower went to North Carolina A&T, became a social worker at Morrison Training School, a reformatory for young Black males in Hoffman. In addition to his position at the training school, he prepared taxes and coached baseball. “If you told him he couldn’t do something,” says his daughter, “he surely would. He excelled.”

Brower became an educator after graduating from North Carolina Central, working at Durham Tech until she retired and moved back to West Southern Pines in 2010. Teaching was a popular career for African Americans in Southern Pines, in no small part because of how much education was stressed at home and in the West Southern Pines schools. Many teachers had advanced degrees and inspired their students to achieve.

“You have to acknowledge the daily humiliation of Jim Crow, the indignity of it, but at the same time, the response to it is dignified,” Charron says. “Upon the end of slavery and in Reconstruction, the first thing Black people understand is that if they want to be landowners — whatever they want to do in freedom — it demands an education. Everything they aspire to is tied to education. It’s crucial to their goals and surviving.”

The daughter of a merchant, Cynthia McDonald graduated from West Southern Pines High School in 1956. “We had exceptionally good educators,” says McDonald, a retired English professor at Sandhills Community College. “I had one lady, Terry Watkins, who taught French, history, civics and Spanish, and made time to take us on a bus to see plays. I wanted to be like her. I didn’t have time to think about what I was missing. Some books we probably didn’t have like the kids on the East side, but we were blessed with exceptional, dedicated teachers.”

Educators had the support of parents backing them up on the importance of academics. Charles Waddell, a multi-sport star athlete who graduated from Pinecrest in 1971 before going to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — where he is the last person to earn varsity letters in three sports — succeeded in the classroom as well. “I always had the threat from my mom (Emma) if I brought home a ‘B,’ I was off the team,” Waddell says. “That’s what kept me straight.”

While he was achieving excellence in sports and in his studies, Waddell, like generations of African Americans in Southern Pines who came before him, saw people running businesses that served the community. One of his uncles, Joe, operated a barbershop in West Southern Pines, having learned to cut hair as a child.

“In a lot of ways, West Southern Pines was self-sufficient in those days,” Waddell says. “There were two or three barbershops, a dry cleaner, stores where you could get produce and meats. There were brickmasons and plumbers, carpenters and mechanics. West Southern Pines was kind of a hub for Black people living in surrounding areas — Raeford, Montgomery County, Vass. We kind of felt a little special in West Southern Pines.”

In earlier times for Blacks who weren’t business owners or tradesmen, work often was physically demanding in grape vineyards or peach orchards. For those who caddied at Pinehurst Country Club, such as another of Charles Waddell’s uncles, Press, the work meant a 12-mile round trip on foot. He got 50 cents for 18 holes in the 1930s before a caddie strike resulted in a pay bump to a dollar. Caddieing at Mid Pines and Pine Needles resulted in a shorter commute. Other people worked as hotel janitors, stable hands, or as maids and cooks for white families on the East side.

Compared to the back-breaking toil in the cotton or tobacco fields that many Blacks left to relocate in the resort town — sometimes returning to farm work when Northerners went up the seaboard for the summer — domestic employment had an upside. Most workers walked to their jobs. Before Pennsylvania Avenue was completed, there was a path through wooded terrain the locals called “Moccasin Slide.”

“You can’t confuse the work people do with who they are in the Black community,” says Charron. “That is a separate identity. Your work is not who you are.”

Reality of Segregation

Churches and civic organizations buoyed spirits and offered a buffer against white supremacy, but the reality of segregation was present until laws finally changed in the 1960s. While Moore County was largely spared the type of racial violence that took place elsewhere in the South, North Carolina was no haven for moderation. In the early 1960s, more KKK members lived in North Carolina than any other state.

For residents of West Southern Pines, daily life brought daily reminders of discrimination.

“In terms of really bad incidents or situations, no, but it was obvious,” says Waddell, 67, who played professional football prior to a career in business and sports administration. “You knew you weren’t able to do certain things. We had to sit upstairs at the movie theater. Even when we went to the hospital we had to go in the back entrance and sit in a different waiting room, a space that was probably 10-feet by 10-feet. Little things like that just made you feel that you didn’t have everything.”

McDonald recalls how women’s clothing stores in Southern Pines would sell clothing and hats to African Americans but wouldn’t allow them to try on the garments. Around 1960, Mitch Capel, then a young child, was in a dress shop on Broad Street with his mother, Jean. Mitch’s father, Felton Capel, was active in town affairs and, with progressive white citizens, pivotal in integrating public accommodations in Southern Pines.

“I don’t know if it was because my mother was very fair-skinned or because of my father, but she was allowed to try on a dress,” Capel recalls. “An African American friend of my mother’s came in the shop and wanted to try on clothing and wasn’t allowed. That was the first time I saw my mother get upset. It was a long time ago, but I’ve never forgotten that day.”

McDonald says of outings to the Sunrise Theater, where Blacks had to enter through a separate door and climb narrow, steep stairs to get to their balcony seats, that “we had a ball upstairs.” Escaping to a movie didn’t erase other slights and insults. “Somebody would call you nigger,” says McDonald, who graduated magna cum laude from N.C. Central in 1960. “Once when we were 9 or 10 years old, a group of us put on our Sunday clothes and decided we’d integrate one of the drugstores. We were tired of going to movies and not being able to get a soda afterward. I can remember the look of confusion on one of the clerks. She told us we could go to the back and she’d get us a Coke. We refused to do that. They wouldn’t serve us up front. But we didn’t let things like that make us bitter. Our teachers motivated us to be the best we can. Most of us did. And quite a few in my class of 23 attended college and finished.”

Growing up, Cicero Carpenter straddled the white and Black worlds of Southern Pines. His mother and father worked for the wealthy Boyd family — his dad was in charge of horses and dogs; his mom was a maid and cook — and resided on the Weymouth estate. Born on that property in 1941, Carpenter lived there until he was 9 years old, when his family moved to a house on Pennsylvania Avenue. Several years later, when the U.S. Highway 1 bypass was being constructed through neighborhoods in Pinedene and West Southern Pines, homes were lost to eminent domain. A handful of houses belonging to Black families near the Carpenter residence was torn down.

“Ours was the only one moved,” says Carpenter, who retired after a long Navy career. “My dad was a home builder in addition to working for the Boyds. They wanted to tear down our house and give him money. He knew it was worth more and protested. Mrs. Boyd got involved, and the state decided they would move it on a truck to New Hampshire Avenue. It’s still there.”

Carpenter followed his father and his uncle, Jesse, into construction, and as a teenager in the late 1950s started building another structure next to his parents’ relocated home.

“The old West Southern Pines jailhouse was behind a lady’s home,” Carpenter says. “I asked her if I could tear down the old jail if I could have the bricks. She told me I could. I used those bricks to build that house on New Hampshire. When I got out of the Navy and built my house in Highland Trails in 1983, I used some of those bricks in the foyer and around the fireplace. Some of the other bricks are around a dogwood in my yard.”

No-Man’s-Land

Those bricks are a link to West Southern Pines’ early days. Crime played a role in it becoming an incorporated town and in the annexation by Southern Pines eight years later.

Jimtown — believed to have been named for one of two African American merchants, James Henderson or Jim Bethea — was neglected by area law enforcement, allowing crime to fester.

Sisters Wilman and Bessie Hasty, whose father, James, became West Southern Pines’ second mayor, in 1927, and whose grandfather helped James Patrick survey Southern Pines when he founded it during the 1880s, described the atmosphere in oral history interviews conducted by the Town of Southern Pines in 1982.

“This was no-man’s-land,” Wilma told interviewer Nancy Mason. “The people did as they pleased.”

Bessie recalled, “We couldn’t get a policeman over here. We did all our chores before it got dark because we didn’t dare go out after dark.”

Nightclubs and bootleggers brought in outsiders. “We had a lot of gamblers and different people come through,” George Ross, who moved to West Southern Pines in 1926, told Mason. “After sundown, you stayed home.”

There were assaults and stabbings in the wee hours. Joe Waddell recalled decades later, “I heard some Yankee say that we had the most beautiful part of Southern Pines.” Yet one area of the Black community came to be called “Blood Field” because of a number of stabbings. There were murders, including the killings of a well-known West Southern Pines eatery/juke joint owner, Amos Broadway, and a Black police officer, John Allen. White authorities contended that Black fugitives sought — and found — sanctuary in the community. One published report from the 1920s, though, details how African American residents conducted a house-by-house search in an attempt to find an outlaw.

On March 3, 1931, the charter for West Southern Pines was revoked by the North Carolina state legislature. The news traveled to New York City, where The Dunbar News, a Black newspaper, lamented the development.

“So this town of, for, and by the Negroes is no more,” the periodical editorialized. “Will the actions of the legislature of North Carolina prove an encouragement to its Negro citizenry? Does it stand to the credit of the state? This is not Jim Town’s tragedy alone.”

In a subsequent edition, The Dunbar News published the opinion of a “leading white citizen of Southern Pines” whose name the publication didn’t disclose. According to this man, the process of revoking the charter hadn’t been furtive and had been necessary because of a high crime rate that he attributed mostly to “a large, floating population of Negroes from all over the South. They are to a considerable extent an undesirable and, in some cases, a dangerous element, and it is no small wonder that the Negro administration has not been able to handle them . . . It was felt, perhaps with some exaggeration, that West Southern Pines was a potential menace to the health and general decency of the general community.” In his rebuttal, he didn’t mention what had to have been a key reason for the annexation: Headlines of crime were potentially bad for the bottom line of white-owned businesses and resorts.

Instead of being bordered on three sides by Southern Pines, it was now formally part of the larger town, which still drew tourists and seasonal residents during the Great Depression.

“There were a lot of people still coming in,” Willa Mae Harrington said in the oral history project. “There were still plenty of jobs we could do. Sometimes there would be ads in the paper, ‘I want a chauffeur, a cook and a maid.’ A whole family could go to the same place and work. That’s how most of the people over here got their houses. By working as caddies, maids, cooks, housekeepers and saving their money. You could always get a day’s work. If you got with a good family you could save while you worked for them.”

Small Steps Forward

Three months after West Southern Pines was annexed, The Pilot reported on the paving of streets, and plans for a water main and fire hydrants for “the thickly settled” part of the Black community.

Those infrastructure improvements were small steps forward for Southern Pines’ African American residents living their lives in a still-segregated era. It would be three decades after Southern Pines annexed West Southern Pines until the town added a Black officer to the police force of the larger municipality, before the bowling alley and golf courses welcomed African Americans and they didn’t have to sit in the Sunrise Theater balcony, before Black women could try on a dress in a downtown shop. Into the 1950s, when the Capel family moved to West Southern Pines, the area’s infrastructure had not kept pace with other parts of town.

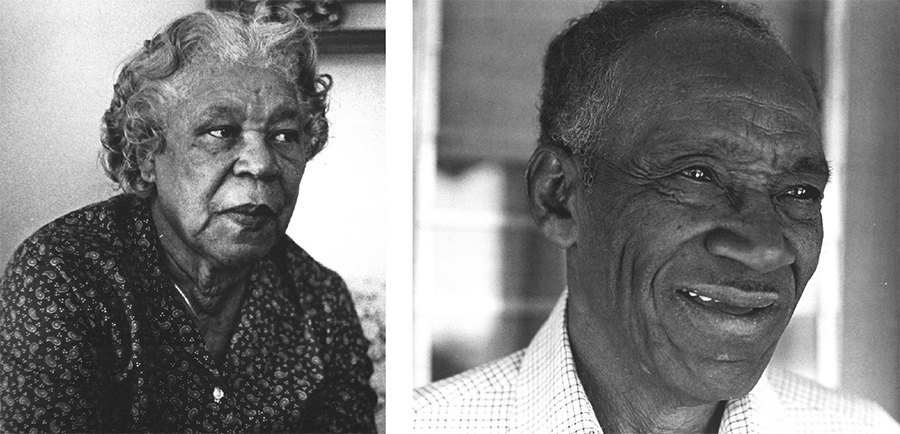

Despite the unequal treatment, African Americans persevered. Oliver Hines’ great-uncle, J. Pleasant Hines, was the mayor of West Southern Pines from 1923-27. Oliver, 68, is a community activist who, like fellow native and longtime Black residents, regrets the loss of businesses on the west side that has gone hand-in-hand with a decrease in the tight-knit spirit he knew growing up. “I wrote down 39 places that used to be here in West Southern Pines and all of them were Black-owned,” Hines says. “Now, there is only a handful. We were thriving at one point.”

Those who remember more vibrant times are eager for a revitalization in West Southern Pines — projects that could celebrate its history while offering an economic boost. The Southern Pines Land and Housing Trust is seeking to acquire the former Southern Pines Primary School (where West Southern Pines High School previously existed) and turn it into a cultural and economic hub.

“The creation of this campus will be a state and national model of how community, government, education and business can work to enhance the lives of citizens and stimulate the economy,” Brower says.

West Southern Pines still sits on a hill, still working to catch a favorable wind. PS