How the Sandhills jump-started the Hall of Fame career of Julius Boros

By Bill Case • Photographs from the Tufts Archives

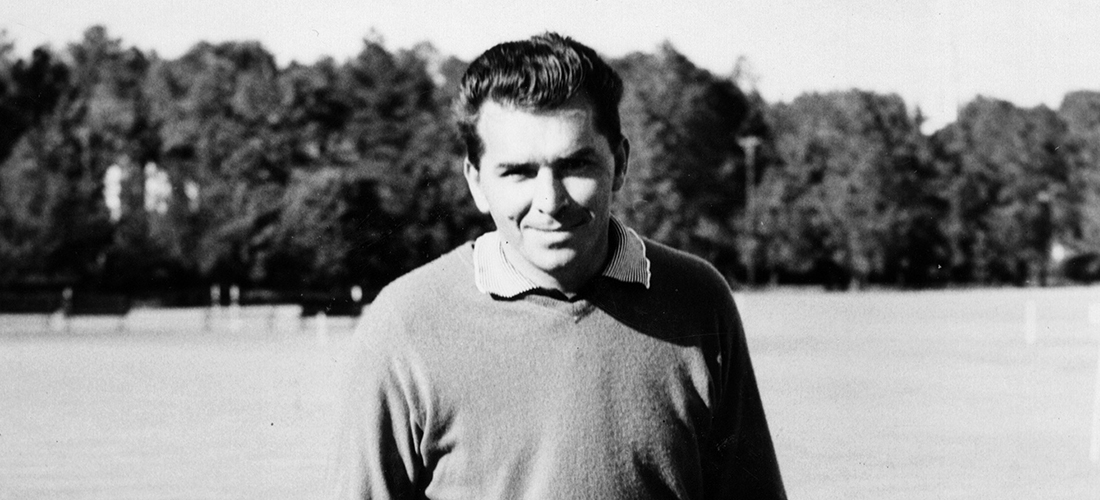

It was a great perk for a bean counter who relished playing golf. Instead of enduring the foul weather months in Hartford, Connecticut, running numbers for the trucking company that employed him as its accountant, Julius Boros got to spend much of that time in 1948 on a golf course in North Carolina’s Sandhills. It wasn’t wholly a lark. There was a bit of daily bookkeeping to do at Southern Pines Country Club, which his boss and frequent golf partner, Mike Sherman, had purchased from the town of Southern Pines two years before. But once that chore was accomplished, Sherman encouraged Boros to play all the golf he wanted.

When Boros asked permission to lay off work the first week of November to compete in a big tournament on Pinehurst’s famed No. 2 course, Sherman happily agreed. At the time, the North and South Open was, if not a major championship, one of the big ones. It seemed unlikely that the amateur Boros, scarcely known outside his home state, would make much of a showing, but cutting his teeth against players like Sam Snead would presumably provide a learning experience if nothing else.

On the Sunday prior to the North and South, Frank “Pop” Cosgrove and wife Maisie, the lessee-operators of the Mid Pines Inn and Golf Club, scheduled a one-day pro-am event on its Donald Ross-designed course. Many North and South entrants, including Snead and Johnny Palmer, signed up figuring that the outing (not to mention the money) would serve as a good tune-up for the main event. Boros wrangled an invite, too.

The Cosgroves’ 20-year-old daughter, Ann “Buttons” Cosgrove — her father thought her cute as one — had assumed responsibility for organizing the event. Buttons, an excellent player herself, invited 30 other equally accomplished female amateurs to play along with the male stars. One of the young women was three-time Ohio Amateur champion Peggy Kirk (Bell), who often palled around with Buttons and her two sisters, Jean and Louise. Peggy spent so much time at Mid Pines it seemed like she owned the place. Later, of course, she did.

Boros, 28 years old and single, attracted the attention of the effervescent Buttons when he worked his way around Mid Pines error-free and carded the day’s low round of 67. With the likes of Snead in the field, Buttons had not contemplated that an amateur would wind up as the day’s medalist. After scurrying about, she produced a spare golf bag from the pro shop to award to the amused accountant.

Boros’ showing at Mid Pines was a perfect springboard two days later at the North and South. Playing quickly, always without practice swings, escaping bunkers using a Spalding 9-iron rather than a conventional sand wedge, Boros’ stellar 68 gave him the first round lead. Only bogeys at the 10th and 17th in the final round prevented him from matching Toney Penna’s winning score of three under par 285. The unheralded amateur’s stunning runner-up finish, tying the great Snead, brought him national attention. One scribe, noting Boros’ husky build and jet-black hair, likened his appearance to boxing great Jack Dempsey, a sport Boros enjoyed as a youth. He had the hands of a powerful puncher to prove it, with fingers as thick as smoked sausages, but a grip as gentle as a tea party.

One of six children of immigrant Hungarian parents, Boros grew up adjacent to the 10th hole of Fairfield, Connecticut’s, Greenfield Hill Country Club. Hopping the fence with his brothers, Lance and Frank, to sneak in some unauthorized golf, the young Boros learned to play fast, developing his trademark rhythmic tempo. When he confided to his parents he wanted to play golf for a living, his Old World father scoffed, “Learn to use your brain, not your back.” After high school, Boros went to work for the Aluminum Company of America and, at the start of World War II, became a medic in the Army Air Corps. He joked that he “fought the war as a laboratory technician” in Biloxi, Mississippi, mostly golfing with the top brass.

After his discharge in 1945, Boros studied accounting for a year at Bridgeport Junior College, then met Sherman, who took him under his wing. As Sherman’s young protégé, Boros directed the employees and handled the financial matters of his boss’s far-flung enterprises. “I had become a businessman, almost overnight,” Boros marveled. Despite his wondrous showing in his first North and South Open, Boros wasn’t yet ready to give up his day job. He was, however, fully prepared to stay in touch with Buttons. Peggy Kirk Bell once recalled that, “Jay (one of Boros’ many nicknames that included Big Jules, Big Julie, Bear and Moose) was a very quiet man, very shy, he said very little. But Buttons was crazy about him. She’d say, ‘Let’s go over to Southern Pines Country Club and see Jay.’”

Both Buttons and Boros acquitted themselves well on the golf course in 1949. Buttons won an important invitational event in Charlotte, and Boros led all qualifiers for the U.S. Amateur, ultimately reaching the quarterfinals, earning him an invitation to the 1950 Masters tournament. In November 1949, Boros returned to Pinehurst No. 2 for the North and South. He finished 17th despite not having his best stuff, a signal to Boros he could prosper in the pro ranks.

Boros gave conflicting accounts of what finally prompted him to turn pro. He told one reporter he pulled the trigger after viewing a driving snowstorm outside his Hartford office window. He also wrote that the encouragement from a few friends at a tournament was all he needed. But Peggy Bell claimed it was Buttons who did the pushing, even asking Snead to convince him. There may well be truth to all three versions. In any event, Boros turned pro on Dec. 15, 1949.

Several Hartford friends interested in backing Boros financially suggested he have Tommy Armour, recognized as golf’s pre-eminent instructor, take a look at his swing. Boros reluctantly agreed. It didn’t go well. Armour’s suggested modifications resulted in repeated shanks by his distressed, self-taught pupil, and Boros declined to return for a second session, spending the next couple of weeks unlearning Armour’s advice.

An arcane rule requiring a six-month waiting period before newly minted pros could accept prize money in tour events meant Boros had time on his hands. He and Buttons competed together in a mixed event at Dubsdread in Orlando, Florida, in March. After that, the Pinehurst Outlook reported that Cosgrove and a Mid Pines friend, Mae Murray, were motoring to Georgia to play in the Titleholders Championship, a major women’s tournament at the Augusta Country Club. According to the Outlook, they were not alone. “The two girls were accompanied by Julius Boros, who recently turned pro. He plans to sharpen his game at the Augusta National course for the forthcoming Masters tournament.” On May 15, 1950, Boros and Buttons were married in Southern Pines’ St. Anthony’s Catholic Church in a double ceremony with Buttons’ sister, Louise, and her new husband, William Weldon.

Boros played a bit part in the legend of Ben Hogan’s comeback in the 1950 U.S. Open at Merion Golf Club. Firing a sensational 68 in the first round, Boros led after 45 holes but finished the third round with a lackluster 77, ruining his chances. Though overtaken by history, his T-9 finish was a remarkable achievement for a first-timer. Two weeks later, Buttons stormed through her preliminary matches and into the final of the Massachusetts Women’s Amateur against another Mid Pines golfing cohort, Ruth Woodward. With her husband rooting her on, Mrs. Boros sprung the upset, winning 2 and 1.

At the end of the PGA’s six-month waiting period, Boros hit the tour in earnest, buttressed in part by steady paychecks coming in from Mid Pines when the Cosgroves put their son-in-law on the payroll as an assistant to tour mainstay, Johnny Bulla. By year end, Bulla had moved on and Boros became the club’s head professional, though his consistent tour earnings meant he never would spend much time behind the pro shop counter. Eventually, younger brother Ernie and nephew, Jimmy Boros, performed that role.

Early in 1951 Buttons learned she was pregnant. Boros acquitted himself well again in the U.S. Open, this time at devilishly difficult Oakland Hills, a course that winner Ben Hogan labeled a “monster.” Boros was the lone competitor not to shoot a round over 74 and his T-4 finish raised the eyebrows of those who wondered if his play at Merion had been a one-off.

With the baby due in September, Buttons assured her husband she was doing fine and that he should play in the Empire State Open instead of pacing the floor of a maternity ward. Things weren’t fine. When Boros heard there were complications, he raced to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Boston. Buttons had suffered a cerebral hemorrhage while giving birth to a healthy son, Jay Nicholas (Nick) Boros, and died the following day.

His wife’s death, “really shook him up,” says Boros’ brother, Ernie. But Julius kept his pain to himself. Two-time major champion Doug Ford traveled with Boros countless hours, coast to coast, during the ’50s. Quiet as a church mouse anyway, Ford says Boros never spoke to him about losing Buttons, nor did Boros mention it in any of several books. Nick, now in his mid-60s, says his father never discussed the death of his mother.

If Boros was to continue on tour, he needed to find caregivers for his newborn son. Pop and Maisie Cosgrove offered to help raise the boy. Nick would rotate with his grandparents between the Cosgrove homes in North Carolina and Massachusetts for the next three years. Following a two month hiatus after the loss of his wife, Boros played a home game in Pinehurst at the North and South Open. Showing little rust, he finished six shots behind Tommy Bolt in the event’s final edition.

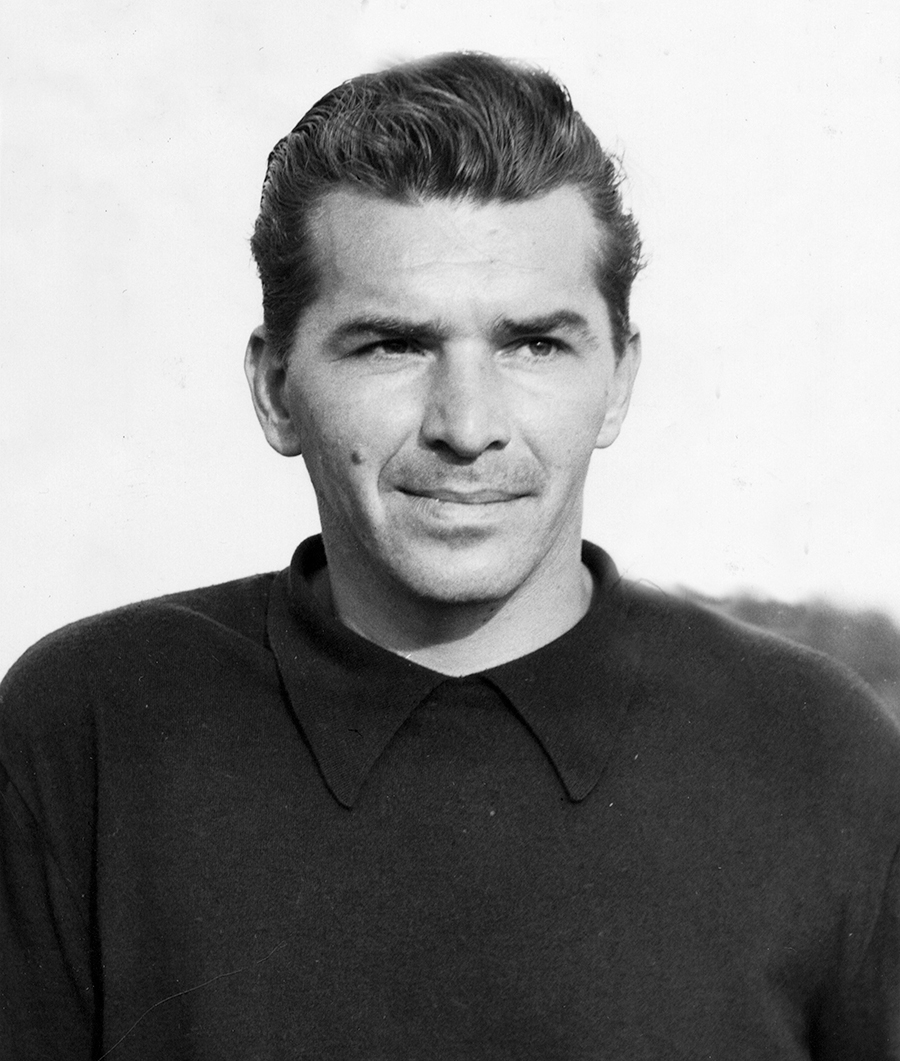

While he continued to be a solid money winner, there were skeptics who wondered whether Boros, with his laconic mien and idiosyncratic swing, had the right stuff to win. His goal for the 1952 U.S. Open at Northwood Club in sweltering Dallas was simple — four rounds of par golf. Midway through, he was two shots over his mark but just four behind George Fazio and Hogan, seeking his third consecutive U.S. Open crown. Many assumed Connecticut native Boros would fade in the oppressive 98-degree heat of Saturday’s 36-hole final. Instead, it was the Texan Hogan who wilted. Boros’ morning round of 68 put him in front at level par. He was three shots clear when he reached Northbrook’s par-3 12th hole but he found the bunker, failed to get out with his second and ambled away unhappily with a devastating double-bogey. “I could see the deep concern on the face of my brother Ernie who was walking silently with me,” wrote Boros. But, playing with the demeanor of a man nonchalantly swinging at dandelions, he negotiated the last six holes in even par, to win the U.S. Open by four over Porky Oliver. His first tour victory had come in America’s national championship. Hogan remarked at the trophy presentation that the former accountant’s play struck him as “magical.”

Hogan wasn’t alone. When Doug Ford, now 94, was recently asked whether he had been surprised he replied, “I was. But he wasn’t. He was a very confident player.” Besides, says Ford, “he did it with my clubs.” Wilson Sporting Goods had been courting Ford to join its elite staff of players and sent him a set of its clubs. When he failed to come to terms with the company, Ford re-gifted the sticks to his buddy. Ultimately, it was Boros who signed on, becoming a valued member of the Wilson staff.

Later that summer Boros added another title in the World Championship of Golf at Tam O’ Shanter just outside Chicago. The $25,000 winner’s purse was many-fold the largest on the PGA Tour. His successes resulted in a small brouhaha. The PGA had another mysterious rule preventing its members from entering the PGA Championship until they had served a five-year apprenticeship. Desperate to have the Open champion in its field, PGA officials announced that Boros could play even though he was considered an “apprentice” member. A few of his peers complained of favoritism. When he learned of the objections, Boros declined the opportunity to compete, opting to preserve collegiality. “I’d rather wait my regular turn,” he said. “I want all the PGA members to be my friends.” He would have to settle for being the leading money winner and the 1952 Player of the Year.

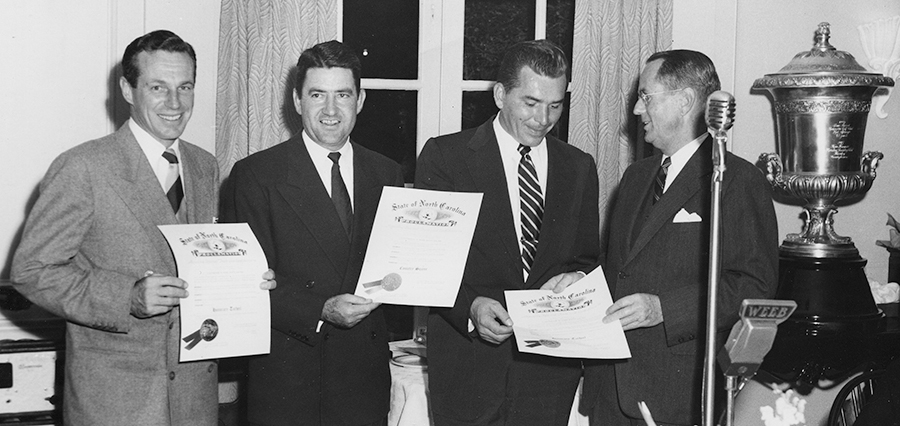

The Cosgroves hosted a big bash celebration in Boros’ honor, including a 54-hole tournament at Mid Pines. At the banquet afterward, Snead spun country yarns and heaped high praise on “Moose.” Pinehurst’s Richard Tufts paid tribute to the other North Carolinians who’d had banner years: Harvie Ward won the British Amateur; Dick Chapman the French Amateur; and Johnny Palmer the Canadian Open. If Boros, who abhorred

public speaking more than four-putting, spoke at all, it was not noted in the newspaper.

In 1953, the Cosgroves and Boros entered into a real estate partnership that resulted in Warren “Bullet” Bell and wife Peggy becoming owners of the Pine Needles golf course, across Midland Road from Mid Pines. The Cosgroves and Boros pooled $30,000 and the Bells $20,000 to purchase the deteriorated facility from the Catholic diocese. Two years later, the Cosgroves, looking to raise sufficient cash to buy Mid Pines, which had come on the market, negotiated the sale of their share in Pine Needles to the Bells. Boros, though not a participant in the purchase of Mid Pines, agreed to liquidate his Pine Needles interest also. Despite doubling his investment in just two years, Boros later expressed regrets. Noting the Bells’ success, he often remarked to Nick, “I never should have sold my share of Pine Needles.”

A year later, Boros met the woman who would become his second wife, Armen Boyle, a blonde flight attendant and the daughter of a Bayside, New York, club pro. Extroverted, gregarious and funny, she and Boros eloped to Aiken, South Carolina, after a whirlwind three-date courtship. Boros’ choice for a honeymoon may have left a little to be desired. “Can you believe it?” Armen says, laughing. “We went to Mid Pines.”

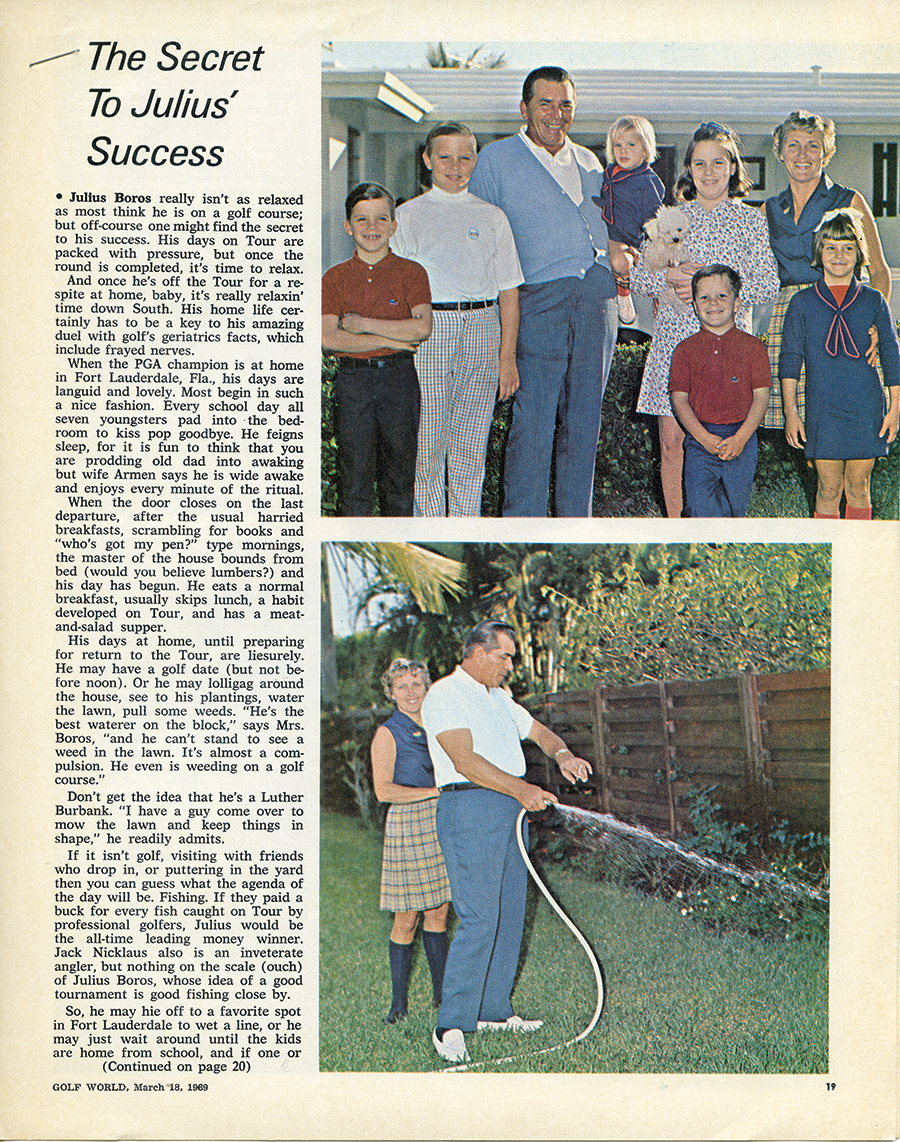

They settled in Florida with 3-year-old Nick in tow. While Boros continued his association with Mid Pines, he spent most of his time off the tour with his family in Fort Lauderdale, where the lakes and nearby Everglades provided ample opportunity to indulge his passion for fishing.

The family expanded quickly. Over a 10-year period, Armen gave birth to six children: Joy, Julius, Jr., Gary, Gay, Guy, and Jody. Including Nick, there were seven young Boros mouths to feed. Boros’ second triumph in the World Championship of Golf in 1955 brought home an unheard of $50,000. Exhibitions for the champion arranged by the tournament’s promoter extraordinaire, George May, paid an additional $50,000. Boros’ successes allowed Armen to pack up the kids in the family station wagon to spend parts of each summer following their father on tour.

Nick recalls those family travels fondly. By the time he entered his teens, he had become a good junior golfer, often showing up on the practice green alongside the pros. Arnold Palmer would putt for quarters against the young Boros. Getting the line on various putts before The King’s arrival, Nick won his share. “How much did we win today?” his father would ask. All the children developed into excellent golfers though their father rarely provided instruction. Nick would occasionally ask for help but his father, a firm believer in finding one’s own way, customarily responded, “Keep swinging. You’ll figure it out.”

After turning 40, Boros’ career appeared on the wane. The Big Three — Arnold Palmer, Gary Player and Jack Nicklaus — weren’t leaving much space in the winner’s circle in the early ’60s. Boros was shut out for nearly three years. His putting, never great, had fallen off. But sometimes help comes from unexpected sources. In a May, 1963 pro-am at Pompano Beach, two amateur partners noticed Boros abruptly picking up his putter and moving his body during the stroke. He resorted to a more compact motion and a widened stance and, suddenly, everything clicked.

In May, he bested Gary Player by four shots to win the Colonial National Invitational. Three weeks later he won the Buick Open. Boros arrived for the U.S. Open at The Country Club in Brookline, Massachusetts, flush with confidence. Consistently high winds made scoring exceptionally difficult. Boros joked that, “most of the cards looked like they had been turned in for the 1913 National Open.” No player either equaled or broke the par of 71 in the final two rounds. With his revitalized putting, Boros salvaged more pars than most and finished 72 holes tied with Arnold Palmer and Jacky Cupit with scores of 293.

In Monday’s 18-hole playoff, buoyed by several wonderful wedge recoveries, Boros took command with a 33 on the front nine. His final round of 70 beat Cupit by three and Palmer by six. “Poker-faced, laconic, a bit on the dour side, he is an efficient rather than an arresting golfer,” wrote Herbert Warren Wind in The New Yorker, “but his colleagues have long respected the smooth, relaxed tempo of his swing and his penchant for being at his best in the big, rich tournaments.” At age 43, Boros had become the oldest player to win the Open, and for the second time he would be named Player of the Year.

Television and Arnold Palmer had transformed pro golf into a hot commodity and, with his victory, Boros found himself in high demand. His Dean Martin-like relaxed approach charmed the golfing public. The fact that he liked to fish just as much as golf added to his laid-back persona. Though so detesting public speaking that he repeatedly turned down the captaincy of America’s Ryder Cup team, Boros was comfortable enough in front of a camera to host a television show. Outdoors with Liberty Mutual ran for 28 episodes showcasing Boros fishing all over the world. Nick remembers his father finagling a special permit to fish along Alligator Alley while it was under construction. Boros took full advantage. “You just about caught a bass with every cast,” Nick says. “Dad would bring home barrels of fish and stock the lakes around home.”

After his second victory in the National Open, Boros continued to win assorted tour events, including three victories in 1967. When he arrived in San Antonio for the 1968 PGA Championship at Pecan Valley Golf Club, the steaming heat was reminiscent of the ’52 U.S. Open in Dallas. Staving off Palmer’s charge, Boros won the championship with the same 281 score he had shot at Northwood 16 years earlier. Now 48, he assumed the mantle of oldest major champion in golf history — a status he still holds. To ward off the heat, Boros donned a structured baseball-style hat bearing the Amana logo. Soon the Cedar Rapids, Iowa, company began offering tour pros $50 per tournament to wear Amana hats, and many did. Unwittingly, Boros had sparked revolutions in style and advertising, and he maintained a close relationship with Amana and its founder and president, George Foerstner, the rest of his life.

In 1972, Pop and Maisie Cosgrove, now well into their ’70s, sold Mid Pines to Quality Inns. When the Cosgroves left, Boros did too. He affiliated with Aventura Country Club (later Turnberry Isle Miami Resort), which was close to his home in Fort Lauderdale. Though he was aging, Julius was forever eager to play. “It would be pouring down rain and we would be getting ready to close,” recalls Nick, who worked in Aventura’s pro shop. “Dad would call and tell us to stay open; that he was going to come hit balls. He never lost his love of the game.”

Though his best golf was finally behind him, the 53-year-old Boros made one last run for a third U.S. Open victory in 1973 at Oakmont, tying for the lead after three rounds but blown away by Johnny Miller’s 63 on Sunday. He considered the performance one of his greatest achievements. “Boros has put on quite a bit of weight and now pads down the fairways at a sort of ursine lope, but age has not affected the lovely tempo of his swing or his almost disdainful calmness under pressure,” wrote Wind. His T-4 finish was his 11th top 10 in the U.S. Open. Ford’s explanation was simple. “Powerful and straight driving,” he says. “And Jay was a great long iron player.” When asked whether he was going to retire altogether, Boros replied with one of golf’s great one-liners. “What would I retire to?” he asked. “I already fish and play golf for a living.”

By the mid-’70s, Boros was spending most of his time in Fort Lauderdale with Armen and the children. With the help of his Amana connections, Boros sent several of his children to the University of Iowa. Nick, Julius, Jr., and Guy all played golf for the Hawkeyes. Nick and Guy became professionals along with their brother, Gary. Guy relished traveling the tour with his dad. “We’d be in the locker room and Lee Trevino would start to tell an off-color joke,” laughs Guy. “Dad would stop him and say, ‘Lee, please, my son is here.’ Lee would say ‘Oh, sorry Moose,’ then go right on with the story. I loved it.”

Guy was good enough to become a respected tour player. When he won the 1996 Vancouver Open, the family joined a select few father-son duos to have won on the PGA Tour. Guy acknowledges it has not always been easy to follow in the footsteps of his dad’s Hall of Fame career. “People think that because my father was so great, I have some sort of built-in advantage. But when I am on the tee, I still have to hit the shot.”

By 1979, Julius had vanished from the tour but he never seemed to lose the knack of seizing the moment. He agreed to partner in a team event with Roberto De Vicenzo in something called The Legends of Golf, the lone televised event for senior players. Boros and De Vicenzo tied Art Wall and Tommy Bolt. The ensuing playoff featured a spectacular birdie fest by both sides until the Boros-De Vicenzo team finally prevailed on the sixth extra hole. Viewer reaction to the fireworks was overwhelming. The memorable playoff was the catalyst that launched what’s now called the Champions Tour. The victory in the Legends was Boros’ last important golfing accomplishment, a fitting farewell to competition.

During the 1980s, Boros’ physical condition slowly deteriorated. Even after the incomparable swing had finally gone out of rhythm, Boros still treasured being on the course. He would drive his golf cart unhurriedly out on the Coral Ridge Country Club to savor the day. His favorite spot to park was under a willow tree near the 16th hole. He would silently, but smilingly, wave at the golfers as they went by. It’s the spot where Julius was found on May 28, 1994, after he had peacefully passed away. Quiet and unhurried. PS