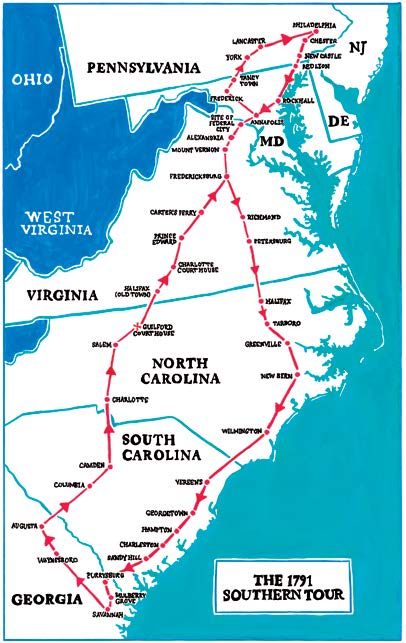

At the end of this stormy day, Washington crossed the Roanoke River, arriving in Halifax around six in the evening for his first true taste of North Carolina. Any visit Washington had previously made to the Great Dismal Swamp hardly counts — it’s like saying you’ve been to Dallas after changing planes at DFW.

It’s not certain where Washington lodged during his two-night visit to Halifax, but it was probably Eagle Tavern. As much as practicable, he refused private lodging during his presidential journeys, either paying his way or agreeing to stay in community-provided accommodation. At times during the Southern Tour, however, there simply wasn’t a suitable public place available. Of course, the horses had to be properly cared for and fed — and some public houses weren’t even reliable enough for that.

Halifax was home to several notable North Carolinians, among them, Congressman John Baptist Ashe, future Gov. William R. Davie, and Willie Jones, who had led North Carolina’s opposition to the Constitution and was no fan of the federal government. Indeed, Jones suggested he would receive Washington as a great man — but not as president of the United States.

Though Washington was greeted politely and treated respectably in Halifax, there’s no doubt that the presence of Jones tempered the enthusiasm. After all, Washington was in town for only two days, but the locals had to live with Jones long after the president was gone.

Samuel Johnston, an Edenton lawyer and the squire of Hayes Plantation, wrote in a late-May letter to James Iredell that “the reception of the president in Halifax was not such that we could wish tho in every other part of the country he was treated with proper attention.” In 2011 — with the specter of Jones long dead and buried — Halifax commemorated the Southern Tour on Historic Halifax Day.

When he reached Tarboro, Washington was impressed by the bridge — a rarity in 1791 — over the Tar River. Apparently, the number of cannon in Tarboro was in agreement with the number of bridges. Washington wrote, “We were received at this place by as good a salute as could be given with one piece of artillery.” Reading Blount, a veteran of the Revolution and a member of the state’s prominent Blount family, led the president’s entertainment.

Washington made his way from Tarboro to Greenville along roads that no longer exist, but his route probably tracked near today’s Route 33. In Greenville, the president, ever a farmer, was pleased to learn about local crops, including tobacco, and was intrigued by tar-making and its commercial value. Nonetheless, Washington wrote that Greenville was a trifling place. Greenvillians shouldn’t fret; the president would say the same thing about Charlotte.

After a night near present-day Ayden, during which Washington worried about the horses going uncovered without stables, the travelers passed near Fort Barnwell en route to New Bern. Likely edging out Wilmington as the largest town in North Carolina in 1791, New Bern turned out smartly for Washington. Mounted militia and town leaders met the president’s party several miles outside town to act as escort. The city provided a new but never occupied home for the president’s stay, the John Wright Stanly home, which still stands and is part of today’s Tryon Palace complex.

On his second night in town, Washington was entertained at a gala at Tryon Palace, and his dance card was full. In recent years, a yellow gown worn that evening by Mrs. Ferebe Guion was shown and evaluated on PBS’ “Antiques Roadshow.” The dress, value unknown, remains in the hands of Guion descendants.

In an age of slow and unreliable mail, Isaac Guion, Ferebe’s husband, took advantage of the presidential traveling party and their Southern passage to send a letter to a friend in Georgia via the president. Imagine the conversation. “Uh, Mr. President, as long as you’re going . . .” I suspect William Jackson, the secretary, handled it, but indeed the letter was carried to Georgia and ultimately delivered.

In the 1940s, A.B. Andrews Jr., a Raleigh lawyer and history buff, came across the letter, acquired it, and presented it to the town of New Bern. It’s kept in the archives in the Kellenberger Room, a wonderful collection of local, regional and state history and genealogy at the New Bern-Craven County Public Library. With all these ties to the Southern Tour, New Bern held major commemorations of Washington’s visit in 1891 and again in 2015.

A cannon salute roared as Washington left New Bern, and the presidential party traveled through Jones County, a namesake of Halifax’s Willie Jones. Longtime Pollocksville mayor and avocational historian Jay Bender wonders why Washington stayed so far inland as he went south from New Bern. The old King’s Highway, the post road that went from Boston to Charleston, came through New Bern and tracked more directly to Wilmington. The reason might have been lodging and services for man and horse, since Shine’s Tavern in Jones County, where Washington put up for the night, enjoyed a good reputation.

The travelers arrived at the coast, a few miles from Topsail Beach, on Saturday, April 23. By late afternoon they linked up with present-day Holly Ridge and the King’s Highway, today’s U.S. 17. Washington lodged at Sage’s Inn, one of the establishments he labeled as “indifferent,” though another traveler of the era described the proprietor, Robert Sage, as a “fine jolly Englishman.”

On Easter Sunday, the presidential party followed the King’s Highway toward Wilmington, resting in Hampstead. Some claim that Hampstead takes its name from Washington requesting ham instead of oysters for his breakfast that morning. There is a large live oak hard by U.S. 17 in Hampstead that supposedly is where the travelers rested. A local DAR chapter has kept the tree marked as the Washington Oak for a century or more.

At some point on Easter, Washington wrote a long diary entry in which he observed that the land between New Bern and Wilmington was the most barren country he ever beheld. The travelers had gone through a vast longleaf pine savanna, and Washington had never seen anything like it.

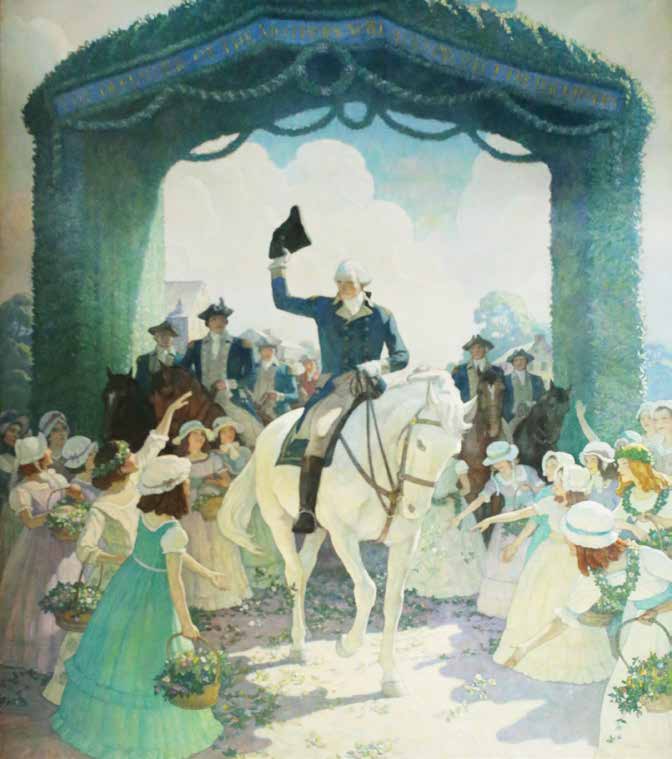

While Washington attended church services several times during the Southern Tour, he made no mention of Easter or attending a service in Wilmington. The Port City’s streets were lined with people to catch sight of America’s hero as Washington was led to his lodgings, a home on Front Street provided by the widow Quince, who gave up her home for the president while she stayed with family elsewhere in town.

Historian Chris Fonvielle, an emeritus professor at UNC Wilmington, says that Wilmington entertained Washington lavishly, and that it was evident that the president “enjoyed the attention from the ladies and drinking with the gentlemen.” Indeed, Washington’s diary indicates there were 62 ladies at the ball. Fonvielle confirms that Washington spent time at two taverns, Dorsey’s and Jocelyn’s. Tavern keeper Lawrence Dorsey famously told the president, “Don’t drink the water!”

Washington’s party continued south on Tuesday the 26th with several stops in Brunswick County. The president met with Benjamin Smith of Belvidere Plantation. Smith was prominent in many ways, a future governor and large landholder, and an officer under Washington’s watch at some point during the Revolution. Southport was originally named Smithville in Benjamin Smith’s honor as he donated the land for the town. Bald Head Island is still known to some as Smith Island, as its original owner was Benjamin Smith’s grandfather, Thomas Smith.

After a night at Russ’ Tavern, about 25 miles south of Wilmington, the travelers stopped at William Gause’s Tavern on the mainland side of what’s now Ocean Isle Beach. Local lore says that the group took breakfast there and went for a swim in the swash, waters that are now the Intracoastal Waterway. The story goes that the president hung his clothes to dry in a large live oak by Gause’s that still stands. Washington crossed into South Carolina early on the afternoon of April 27.

The president continued his travels through South Carolina and Georgia and returned north to North Carolina in late May with stops in Charlotte, present-day Concord, Salisbury, Old Salem and Guilford Courthouse. Washington moved fast on the northbound return. His departures were often at four and five a.m. after one-night stays. In Charlotte, the president was hosted by Thomas Polk, a former officer during the Revolution and the great-uncle of future president James K. Polk. Washington lodged at Cook’s Inn on the corner of Trade and Church Streets where reportedly he left behind his powder box — not gunpowder but powder for body and hair.

Washington enjoyed two nights in Old Salem. Though he planned to spend only one evening, the president agreed to spend another day upon learning that North Carolina governor Alexander Martin was on the way to meet him but wouldn’t arrive until the next day. The president was impressed by the Moravians’ “small but neat village” and their ingenuity, having devised a clever water distribution system.

Before the creation of Greensboro, the county seat of Guilford was Guilford Courthouse, the site of a significant battle of the Revolution just 10 years earlier. Throughout the Southern Tour, Washington enjoyed seeing the battlegrounds that he had long read about. This was no different. “I examined the ground on which the action between Generals Greene and Lord Cornwallis commenced,” wrote Washington.

His last stop in North Carolina was an overnight stay with Dudley Gatewood in Caswell County, just south of the Virginia line. Gatewood’s home was disassembled and moved to Hillsborough during the 1970s, where it was reassembled and served many years as a Mexican restaurant. Sadly, the home gradually fell into disrepair and was torn down in 2024.

The travelers continued north through Virginia, spending time at Mount Vernon and in Georgetown, Maryland, where the president met with area residents to make plans and arrangements to create the new federal capital on the Potomac. Washington celebrated July 4 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and the travelers arrived back in Philadelphia on July 6. Church bells pealed to honor his return. The odometer had turned nearly 1,900 miles and Washington noted that he had gained flesh while the horses had lost it.

America’s first president never again went south of Virginia, but his visit to North Carolina and the South in 1791 was a great success. The Stanly House in New Bern and Salem Tavern in Old Salem are the only extant places where the first president slept, but the legacy is alive and well. The journey was a remarkable physical feat, and politically, Washington’s presence among the citizens and leaders of the nascent United States created considerable good will and acceptance of the new federal government, helping to cement the legacy of 1776.