NATURALIST

The Day a Whale Came to Southern Pines

Momma T, a train, and one big mystery

Story and Photographs by Todd Pusser

As the end of the year winds to a close, I can’t help but feel nostalgic about the holidays of my youth. Among my most vivid and cherished Christmas Day memories are the family gatherings at my late grandmother’s house in Eagle Springs. Home-cooked meals, touch football in the yard with cousins, seven-layer cakes, lots of laughter, and gifts aplenty. At the center of it all was our matriarch, Irene Thomas.

“Mamma T,” or simply “T,” as I liked to call her, was, by any measure, an extraordinary woman. Born on a farm near the headwaters of Drowning Creek, my grandmother lived a long and productive life, passing just a few weeks before her 93rd birthday. During that time, she raised two sets of twins, played the organ each and every Sunday at church, maintained a long and productive career with the N.C. Department of Social Services, and continued to work helping others at the Penick Village in Southern Pines long after retirement.

Nestled in a corner of the laundry room in her small house was a wooden bookshelf lined with a complete set of the World Book Encyclopedia, the black and white leather-bound 1967 edition. The “W” volume held my attention the longest, for that’s where the account of whales was found. I spent many a Christmas lost within the pages of that massive tome.

Mamma T recognized my fascination with wildlife early on, and went out of her way to foster and nurture that passion. She routinely clipped newspaper articles about whales and saved them for me. She even took me on my first airplane flight to Washington, D.C., where we visited the National Zoo and the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. And each year at Christmas, she gifted me a subscription to National Geographic magazine.

Spending her entire life in landlocked Eagle Springs, my grandmother never observed a whale in the wild. However, over the years, she would occasionally recount the time she did see an actual large whale, up close and personal, right in the heart of Southern Pines. It was around the time the country was in the throes of the Great Depression and, though she was a young child and could not recall many details, she knew the whale arrived in town by train. Her family journeyed all the way from Eagle Springs — a bit of a haul in those days — to see the leviathan stretched out on a railway car. She remembered paying a dime to view the traveling exhibit.

As a kid who loved whales and trains, hearing her story sparked my imagination. Later, as an adult who worked as a marine biologist by profession, I began to wonder about that story and that “whale train.” Where did it come from? Who sponsored it? What type of whale was on the train?

My grandmother retained her mental acuity till the day she passed away in 2015. In fact, we talked about the whale in Southern Pines just a few months before her death. I’d always assumed the whale had washed ashore along a North Carolina beach and was loaded onto a train car that toured the state. Perhaps some local entrepreneur, an ad hoc P.T. Barnum hoping to capitalize on the public’s fascination with sea monsters or the biblical parable of Jonah, had made the arrangements.

Whales have washed up on the beaches of North Carolina for millennia. Records dating back to the mid-1600s describe the first settlers of Colington Island selling over 80 barrels of oil rendered down from dead whales, known as “drift whales,” cast ashore on the northern Outer Banks. Today, one can find numerous skeletons of large, beach-cast whales hanging from the rafters of the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in downtown Raleigh, including an immense sperm whale (of Moby Dick fame) that washed ashore in Wilmington in 1928. Did the remains of that whale travel by train from Wilmington to Raleigh via Southern Pines?

I thought perhaps the answer to that question could be found in a small booklet titled A Whale Called Trouble, published by the museum in 2004. It tells how the bones of the sperm whale were buried in a shallow grave on the beach for over 6 months and then dug up and transferred to Raleigh by two trucks. Clearly this was not the whale Mamma T saw in her youth. Back to square one.

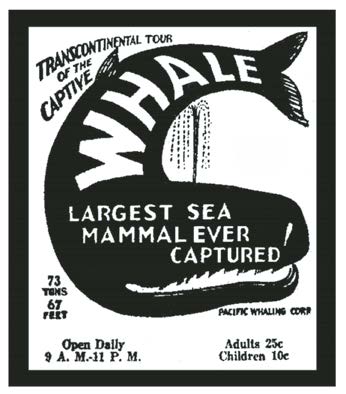

It wasn’t until recently that I discovered what I believe to be a clue about the origins of the great whale of Southern Pines. While researching historic fishing accounts of sawfish and sturgeon in our state’s waters, I stumbled across an advertisement in an April 28, 1933, edition of the Roanoke Beacon, published in the small town of Plymouth, in the eastern part of the state. Beneath a black and white photograph of a dead whale lying on its side on a shipping dock, a caption reads:

It took eight hours and 15 minutes to capture this monster whale, which will be on exhibition here in a few days. The Pacific Whaling Company fleet captured the whale and embalmed it. Many difficulties were overcome in placing him on a railway car. An actual close-up of the whale can be obtained by visiting the exhibition near the depot when it arrives in the city. It will be here next Thursday afternoon.

Surely, this must be it. The account has all the elements: a train, a whale, and a date that matches up. In 1933, my grandmother would have been 11 years old.

So, I did a deep dive into the history of the Pacific Whaling Company, which caught and killed whales off the coast of California in the early decades of the 20th century. It was the heyday of commercial whaling, during the pre-plastic era, when whale blubber was rendered down to valuable oil, and whalebone and baleen were used for a variety of purposes, everything from ladies’ corsets to chimney-sweep brushes.

From 1930 to 1937 the Pacific Whaling Company sent out specially designed railway cars, each loaded with an embalmed dead whale, to towns all across the U.S. and Canada. Along with the whales, actors in sailing attire, often portraying ship captains, would regale audiences with tales of high seas adventures. Occasionally other marine curiosities, such as stuffed penguins, were exhibited alongside the whales. A small admission fee was charged for these “educational exhibits.” By some accounts, the “whale on rails” was quite profitable for the company. In some years, Pacific Whaling grossed more than a quarter of a million dollars, an extraordinary sum for that day and age, especially during the Depression. Even by today’s standards it’s a big chunk of change.

Having now seen many historic accounts of these whales on trains throughout the country, I feel confident that the Pacific Whaling Company was the source of the whale that came to Southern Pines during Mamma T’s childhood. Still, there are unanswered questions. What type of whale did she see all those years ago? A blue whale? A humpback? And what were the dates when the whale train came into Southern Pines? I have more work to do.

But this Christmas, like so many, I’ll be thinking about whales and my late grandmother. It’s funny how her seemingly insignificant story of a whale on a train, told with such love and enthusiasm, has left so large an impression on me. Mamma T gave me one of life’s greatest gifts: the gift of wonder. For that, I am forever grateful.