Almanac August 2024

August is a hammock, a daydream, a nap in dappled light.

These searing summer days, the trees offer respite from an unrelenting heat. There, by the water. Can you imagine two more perfectly situated trees? Two more hammock-worthy specimens?

The trees have spoken. This is the spot. You cinch one rope around the trunk of a sturdy birch, secure the hammock; repeat at the trunk of a tulip poplar.

In the shade of these nurturing giants, summer softens. Sunlight flickers through a veil of green. A welcome breeze gently rocks you.

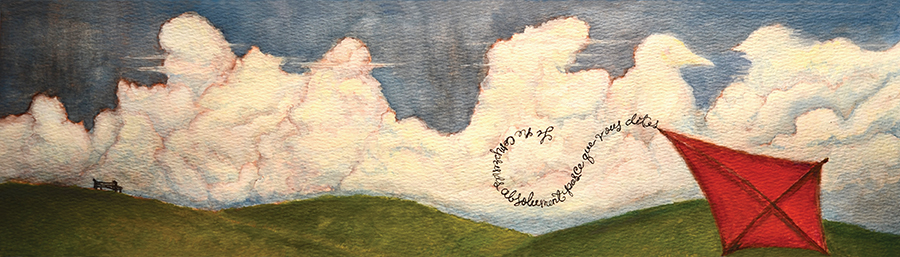

Below the canopy, cumulus clouds float across your field of vision, inviting your inner child to play.

A carousel horse becomes a Bengal tiger. A whiskered dragon shifts into a humpback whale. A never-ending carnival drifts by in slow motion.

Before long, you’ve drifted, too. As you sleep, suspended beneath the trees at the height of summer, something else is shifting.

The days are growing shorter. Soon, the last swallowtail will have vanished like a dream. The last dragonfly, too. Once more, the trees will prepare for their grand finale.

Through the dancing leaves, a sunbeam caresses your cheek, tenderly stirring you awake. The shade has revived you. Somehow, your nap has changed everything.

Beyond the trees, sunlight graces a lush and vibrant Earth. Subtle as it seems, the season is softening. Find the birch and the poplar and see for yourself.

The change always comes about mid-August, and it always catches me by surprise. I mean the day when I know that summer is fraying at the edges, that September isn’t far off and fall is just over the hill or up the valley. — Hal Borland

A Bat Rap

A Bat Rap

International Bat Night is observed on the last full weekend of August — and has been, annually, for nearly 30 years.

Our own state is home to 17 species of bats, creatures of the night essential to pollination, seed dispersal and pest control.

Did you know that a single bat can consume over 1,000 mosquitos in just one hour? That’s over 1,000 reasons to celebrate and protect these night-flying wonders.

Bellyful of Sweetness

Late summer means the last of the blueberries, sure. But can you say muscadines for days? And let’s hear it for those early pears!

Late summer means the last of the blueberries, sure. But can you say muscadines for days? And let’s hear it for those early pears!

Because pears ripen from the inside out, they go from green to mush in a sugary blink. How do you know when they’re ready for harvest? They’ll show you.

Observe the color. Now, gently lift the fruit and give it a tender twist. If it’s ready, the pear will release itself with ease. If the pear holds tight, you’ll want to give it more time.

“There are only ten minutes in the life of a pear when it is perfect to eat,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The poet had a point.

Give the pears a week to ripen post-harvest. If you miss the window, there’s always compote. PS

M

M

A

A

G

G

They were in the little dining room off the kitchen when he finally told her. He paced about, motioning with his hands.

They were in the little dining room off the kitchen when he finally told her. He paced about, motioning with his hands.

T

T