The Beauty in the Barrens

The triumph of Tufts,

Olmsted and Manning

By Claudia Watson

Photographs by John Gessner

Beneath the canopy of a brilliant blue June sky, the land lay battered. An abandoned tramway, used for hauling lumber and turpentine, stretched through a landscape marked by scraggly oaks and a few spindly pines. Wild hogs and sheep foraged the nearly barren sand.

On that day in 1895, James Walker Tufts, accompanied by surveyor Francis Deaton and two other men, inspected a 100-acre parcel of his new landholdings in southern Moore County — the site for his proposed town. The first task was to settle where to place the survey stake marking the land’s center point.

They made camp for the night in an old lumber shelter, boarded on two sides. The next day, Tufts walked to a broad, shallow, basin-like plot of ground. He had neither an ax nor the proper fatwood stake but succeeded in finding an old piece of timber, which he drove into the ground. Deaton marked the spot on his rough topographic map “Beginning Point.”

Characterized by its rolling terrain and deep, coarse sand, and predominately covered by tall longleaf pine, the land once had been part of a 90-million-acre wilderness stretching from southeastern Virginia in the north, to eastern Texas in the west, and as far south as the upper half of Florida. The longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) could live up to 500 years, grow to 3 feet in diameter and reach a height of 120 feet.

Soon, this region’s harsh but beautiful landscape was under pressure. The tall, straight, longleaf timber did not go unnoticed by the steady stream of European settlers. They followed the Cape Fear River and its tributaries to the pine barrens of Moore and Richmond counties to find land for intensive high-yield farming. But the sandy soil was unsuitable, so they turned to the pine forests for their livelihood.

The vital longleaf ecosystem was devastated, the target of exploitation: first for its lumber, to build homes, buildings and masts for ships. Later its resin was used to make tar and turpentine, essential naval store products that supported shipbuilding efforts. With the arrival of trains in the 1800s, the trees were felled to build railroad tracks. Ultimately, those railroads were essential to Moore County’s development and Tufts’ arrival.

James Walker Tufts, a successful and wealthy entrepreneur from Massachusetts, was captivated by the area’s warm climate and therapeutic pine-scented air. He used his considerable wealth to locate and purchase nearly 6,000 acres to build a winter retreat in an area laid waste by decades of timbering operations.

The project, seen as essentially benevolent, would provide respite and recreation for “the betterment of his fellow humans.” In particular, he focused on ailing individuals — including those with early stage tuberculosis who were mistakenly, and commonly, believed not to be contagious — seeking a warm, dry climate while recovering. Learning quickly that all stages of the disease were contagious, he rebranded his retreat into an outdoor sporting venue, with recreation as its primary business.

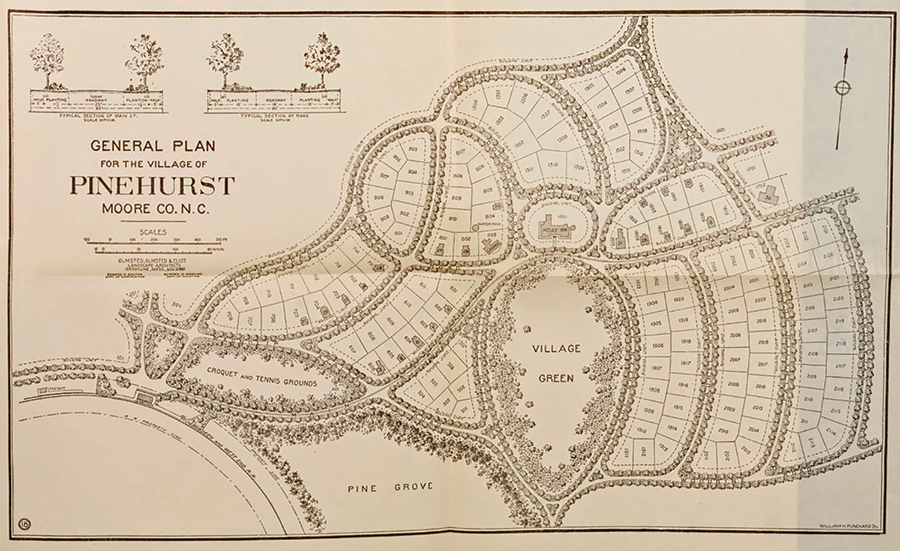

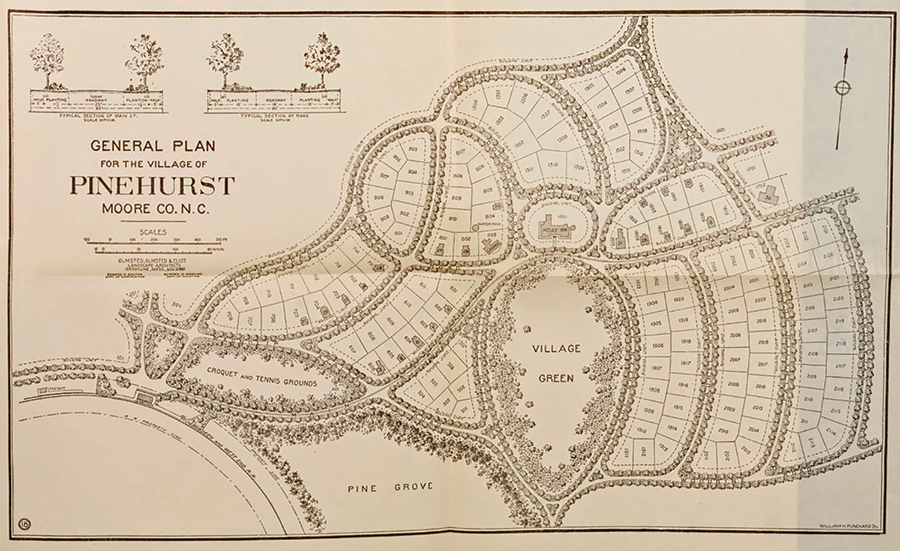

Tufts envisioned a charming New England-style village set in the 100-acre core of his land holdings. Armed with Deaton’s survey denoting the town’s center, and immediately after acquiring the land contracts, Tufts turned to the most prestigious landscape architecture and design firm in the country — Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot — to design the town he imagined.

Olmsted’s plans were renowned for the role that landscape architecture played in improving quality of life. His concept was that nature not only lifts the human spirit, but strengthens and restores it. He also believed that every human being, regardless of social or economic status, had a right to that experience. Tufts’ principles and Olmsted’s were synchronized.

Olmsted, however, was in his 60s and affected by mounting health problems, including dementia, which soon sidelined him. During the summer of 1895, just as Tufts’ project was underway, Olmsted retired. That year, his stepson John Charles (“J.C.”) Olmsted and architect Charles Eliot carried the firm’s workload. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was busy with George W. Vanderbilt’s Biltmore estate project.

Olmsted’s catalog lists Pinehurst village, but it was small compared to other projects. A visit report dated June 20, 1895, provided by J.C. Olmsted, indicates that Tufts initially spoke by phone with another member of the firm’s staff and provided his conceptual overview for the village.

A general plan would cost $300, including supervision, planting that year, and time for a planting assistant. “Traveling expenses were extra. No visits were to be made by the firm, only by W.H. Manning that fall,” noted the proposal.

On July 3, 1895, Tufts met with Fredrick Law Olmsted Sr. and J.C. Olmsted at their offices in New York, and within days the firm provided a plan for the town drawn in ink on linen paper. Tufts quickly accepted it and then, eager to see his vision move ahead, ordered 200 water oaks.

The project’s 1895 promotional brochure said, “It is understood, of course, that the extensive plans that have been made for beautifying the village with greenery will require considerable time before they are carried out to completion. The wilderness cannot be made into a garden in a day, even with the most liberal expenditure of money, energy, and skill.”

Warren H. Manning had joined the Olmsted firm in 1888 as its planting supervisor, where his extensive horticultural knowledge quickly expanded his responsibilities. Mentored by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. in his early years with the firm, he oversaw over 100 projects, including planning the metropolitan park systems for Boston, Louisville and Milwaukee. In addition, he supervised the acquisition of thousands of acres for Vanderbilt’s Biltmore estate and, beginning in 1893, became involved in planning its arboretum.

Manning’s vocation had its roots in his New England childhood. He credited his father, an esteemed horticulturist and nurseryman, for his appreciation of nature. He absorbed his father’s fascination with plants of all types, particularly the newly fashionable American native plants. Though he did not have formal training in landscape design, he traveled extensively with his father to commercial greenhouses and gained experience as the manager of his father’s plant nursery.

When Manning was 27, he wrote Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. seeking work and stressing his horticultural skills, particularly his success moving large trees. He wrote of his “knowledge of hardy trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants & the treatment & the effects produced by them.” He underscored his literacy in common and botanical names and botanical relationships.

The Pinehurst village project progressed with J.C. Olmsted the lead partner. Designing the landscape without inspecting the site wasn’t feasible, so in September Manning was sent to meet Tufts and explore the property. He and Tufts traversed the 100-acre town site taking in the views from atop ridges and gaining knowledge of its topography as well as the natural scenery.

When he returned from his visit with Tufts, he described the area as “largely sand hills laid to waste” from timbering. But he added with enthusiasm that it also held “long valleys with springs, streams, and narrow wetlands” with small trees, shrubs and herbs.

The moist valley areas and wetlands were the most exciting and attractive for plants, birds and other wildlife. “The bottoms of the wet valleys are the natural winter and summer garden spots of the region and a constant source of delight to one who appreciates varied forms of plant life,” he wrote.

The dry upland was less appealing. Here, scrubby and stunted oaks and spindly pine trees, either dead or deeply gashed, littered the area marked by tufty grasses and bare sand. It is “a ghastly ruin of fallen trunks, blackened stumps, and decayed branches, all testifying to the devastating methods of the turpentine distiller and the lumberman,” Manning said in the Pinehurst Outlook in December of 1897.

“It became at once evident that an artificial means must be resorted to if an attractive evergreen landscape is to be provided during winter, and an abundance of flowers during early spring, the most active season of visiting guests and residents, most of whom being from the colder states expect very different and more attractive conditions than those prevailing at their northern homes, conditions which would not be presented by the original landscape,” he wrote.

Delivered Oct. 30, 1895, the landscape plan offered lushness in exchange for the dreary and monotonous landscape. “It will be replaced by a varied and interesting local scenery in which green foliage will form all the foregrounds, drape the buildings, afford shade on sunny days, and conceal the raw earth . . . with perennial verdure,” the plan noted. The comprehensive proposal recommended a heavy use of evergreen plants — preferably broad-leafed evergreens.

An oval-shaped “Village Green” meant for active use was the plan’s central feature. Located in a broad, shallow amphitheater-like valley, it was surrounded by winding roads that hugged the natural grades, radiating outward from the green. Charming New-England style cottages, most with porches, were sited on uniformly sized lots along roads often named for trees — Magnolia, Dogwood, Laurel, Maple, Orange and Palmetto. The town’s layout provided an enhanced sense of space with the boundaries opening to new views.

Near the railroad tracks, to the south, stood a dense grove of longleaf pines that offered a glimpse of the forest that once covered the land. The hotel, town office, a store and community casino were placed in the center of the village. Evenly spaced trees and dense plantings would offer a naturalized effect throughout all of this.

To achieve the lush setting for the town, Manning specified and located the trees, shrubs and ground covers based upon the location, carefully framing the views from cottage windows and the hotel to provide a verdant appearance in every season.

The planting scheme recommended 222,600 plants in nearly 90 varieties, importing 48,000 plants from France and 1,500 from nine American nurseries. The balance of the plants would be purchased, collected later, or propagated at a nursery in Pinehurst.

Realizing the initial cost would be great, the architects justified it by saying that the cost would be insignificant once the plants established themselves. “It is absolutely essential to making the vicinity of a village of the sort you are building agreeable and homelike in the winter,” the landscape plan argued.

Evergreen shrubbery was primarily local and native material. “It was recognized . . . that native plants must be depended upon chiefly for the results we wished to secure, for they only could be procured in sufficiently large quantities to do, at a reasonable cost, the immense amount of planting that was required in the town,” Manning wrote later in the Pinehurst Outlook. He preferred native material because it was fully adapted to the local soil and weather conditions, and needed less water, fertilizer and overall maintenance to thrive. As an added incentive, they remained balanced with nearby plants instead of overtaking the landscape like invasive species.

The plan included dozens of native plants collected from private property or the swamps within about 100 miles of Pinehurst, but the effort became costly.

“You better depend upon your greenhouse men to do your propagating from seed instead of attempting to root from cuttings, which would be very difficult if not impractical,” Manning suggested of the local native plants. “You will get more plants at less cost,” he added, offering an unconventional and less time-consuming method for preparing the seeds for germination.

To help implement his plan, Manning brought in Otto Katzenstein, a German seedman who worked for the Olmsted firm and was enamored with native plants. Katzenstein would develop and manage the town’s nursery and crews who gathered plant material to use in Pinehurst.

With the planting proposal approved, Manning shifted his attention to installation and began with the Village Green, which provided the central recreational setting for the community.

Planted with rich layers — groundcovers, shrubs, and trees above — the Village Green provided an area for restful recreation and the study of nature. Selected for their growth habit and the various tints of green and texture they offered to the foreground, the trees and shrubs provided an indistinct border.

Multiple “plantations” were set upon the Village Green and anchored by evergreen (not coniferous) native trees — Southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), evergreen oaks and Carolina cherry laurels (Prunus caroliniana). Then, the smaller groups of single trees and shrubs would spill out from the larger tree groups and blend into the foreground, creating a constantly changing play of light and shadow.

The understory featured non-native camellia, boxwood, pyracantha, azaleas and cherry laurels (Prunus lauroceracus). These mingled in groupings with native sweet bay magnolia (Magnolia gluca), holly, gall-berry (Ilex glabra), wax myrtle (Morella cerifera), fetter bush (Lyonia lucida), and mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia). Wisteria would festoon the tall pines with its drooping clusters of flowers. Osmanthus, nandina, wisteria, elaeagnus and privets, all non-natives, would adapt and naturalize.

The transition to the sunny central area of the Village Green required 40,000 groundcover plants. In that time, landscape architects commonly used non-native species for their visual appeal and ability to colonize, often filling a derelict space. Here, non-native Japanese evergreen honeysuckle, English ivy and periwinkle covered the trunks and branches of the deciduous trees, keeping the areas green with foliage, even in the winter. The unruly honeysuckle required regular shearing to keep it within borders and at ground cover height.

Many experimental plots of grasses were grown from seeds secured from various parts of the county, but most failed to tolerate the conditions. Only winter rye grown from seed made a good start in the Village Green, but it finally drew Tufts’ ire.

“Winter rye was bravely endeavoring to cover the whiteness of the sand. Patches of rye growing on the village green served only as a mockery of the word green and of the deep lush turf of the New England commons after which this area was patterned. On every hand, there was white, infertile soil,” Tufts wrote.

Manning adjusted the plan and removed the unsuitable ground cover creepers and turf. Next, he recommended covering the bare sand with fresh pine straw and later planted dozens of longleaf pines.

In the 1800s, lovely shade trees were becoming rarities, and lovers of arboriculture would travel miles to see them. An evergreen canopy was essential for Pinehurst village and would lend much-needed shade and character, not typically found in the South.

Village streetscapes received 1,500 trees, and the homesites, 500. Native trees used throughout the plan included longleaf pines, red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), dogwoods (Cornus florida), eastern redbud (Cercis canadensis) and sourwood (Oxydendrum arboretum).

Oaks, the most essential of all native trees and known to sustain a critical and complex web of wildlife, were among Manning’s favorites. Drawn by their lofty canopies and color shifts throughout the seasons, he used willow oak (Quercus phellos), live oak (Quercus virginiana), and swamp laurel oak (Quercus laurifolia) as specimens to edge village streets and grace homesites.

Today, the village’s landscape is full of the towering oaks, Southern magnolias and cedars planted between 1895-1898. Thirty-four of those trees on the village of Pinehurst property and bordering the Village Green are protected and designated heritage trees including several magnolias and hollies along the walkway near Given Memorial Library. In addition, dozens of other majestic trees at Pinehurst Resort and on private land continue to provide intrinsic value to the community. Most of the Village Green’s longleaf pines are at least 100 years old.

At Pinehurst’s founding, the only remaining dense stand of longleaf pines in the area, known as the Pine Grove, became a favorite attraction. There, a friendly herd of deer shared their domain with gorgeous peacocks, attracting visitors with children in tow who enjoyed the teeter-totters and swings.

Manning specified the addition of 50,000 trees, mostly longleaf pines, for the Pine Grove site and the borders of the village. He also included exotic conifers known for their shape, texture and color in the landscape. Adapted well in the South, the graceful deodara cedar (Cedrus deodara), Japanese cedar (Cryptomerias japonica) and cypress augmented the native growth.

The workforce completed the village center’s buildings, necessary infrastructure and 14 residences within about six months. With each area’s completion, Manning’s workers began installing the landscape.

The updated general plan drawn in November 1895 for Tuft’s promotional efforts reveals the enormous scope of work required to connect passages full of scenery for the village, its roads, walkways, and finally, the homesites — where visitors observed the details more closely. The initial homesites were small and set back 36 feet from the street. Manning wanted to ensure that “each home then appeared to be set in its own private forest.” So, 13,400 evergreen ornamental shrubs, in addition to 500 homesite-designated trees, provided generous coverage, plant diversity and individuality to each lot.

The early streets were 16 feet wide and built using sand and clay from a local pit. A sloped 16-foot shrubbery bed and 5 feet wide sand and clay sidewalks bordered each side of the road. The shrubbery beds absorbed stormwater runoff from the road and sidewalks, benefitting the ornamental trees, shrubs, and flowers planted there.

The streets and sidewalk areas received 1,500 trees and 17,000 plants. Many of the evergreens used on the Village Green would be repeated for these areas but softened by clusters of mahonia and winter jasmine (Jasminum nudiflorum). Low evergreen groundcovers, including St. John’s wort (Hypericum calcycinum), wintercreeper (Euonymus radicans) and many types of roses, covered the edges of the planting strips providing seasonal interest.

After working throughout 1895-96, Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot ended their contract with Tufts. The firm recommended Manning to assume the project, which he did with vision and energy. He quickly established a farm with a large barn housing a herd of Holsteins and Jerseys cows, then in 1898, started Pinehurst Nurseries.

Otto Katzenstein, who tended the town’s nursery during its founding, became superintendent. He propagated and grew nearly 100 varieties of native trees, shrubs and herbs that succeeded under the challenging growing conditions of the longleaf pine region and offered them to a broader community through a catalog.

The catalog also offered a variety of non-native “thrifty” plants, including pansies, pinks, roses and a hardy form of the English violet, discovered in an old Southern garden. Those plants adorned the landscape of the Carolina Hotel on its opening day, Jan. 1, 1901.

A winter resident wrote in the Pinehurst Outlook, “Looking out my window . . . I see planting spaces filled with native evergreen shrubbery — magnolias, holly, gall berry, bay flower, yucca, honeysuckle, ground roses, pansies and violets and the whole surrounded by a vast green lawn. Think of it — a pretty green lawn with violets in profusion right out in the open in January — as pretty as our own New England lawns in June.”

While the involvement of Frederick Law Olmstead, Sr., in the village plan has often been a matter of conjecture, in a 1922 letter to Leonard Tufts, Manning wrote, “I know Mr. Olmstead’s personal interest in Pinehurst was a keen one, because of his sympathy with your father’s desire to establish conditions that would make it possible for people who were not well to come to Pinehurst and live for moderate costs . . . and I remember very well his keen interest in my report on conditions that I found there.”

Over the next three decades, Manning continued to work with the Tufts family to extend their vision of the Sandhills. His national practice included more than 1,600 landscape projects throughout North America. One of the 11 founders of the American Society of Landscape Architects, he is considered one of the most significant landscape architects of the 20th century and its first environmental engineer.

Tufts’ vision and collaboration with the Olmsted firm and Manning’s ability to visualize the true nature of the place restored life to a land of nothingness — giving it, and us, a land of unexpected beauty. PS

Claudia Watson is a frequent contributor to PineStraw and The Pilot and finds joy in each day, often in a garden.