Time and weather take their toll on Addor’s Rosenwald School

By Jim Moriarty

You have to step carefully. There’s a massive hole in the roof directly over what was once the kitchen, just inside the back door. The floor still supports your weight. At least for now. An old sign on the wall left over from when it was the community center says “Welcome Addor Friends” but lays down the rules to a vacant building: No Alcohol or Drugs; No Arguing; No Gambling; No Fighting; No Profanity; No Weapons of Any Kind; No Smoking.

Over one door it says “Library/Classroom.” There are still books on the shelves, an Encyclopedia Britannica and a set of World Books so old the Soviet Union still exists. Chairs small enough that a child’s toes can brush the floor are stacked on equally tiny desks built three abreast.

In the “Auditorium,” a glass case shields old photos and scrapbooks of newspaper articles. There’s a dusty ping-pong table and a piano with notes that clunk off the walls of the empty room if you happen to plunk the right key, leaving little behind but the echo.

The Lincoln Park School was built in 1922 on South Currant Street in Addor, the African-American town on the southern edge of Pinebluff where lumber and turpentine workers scratched out an existence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1890 it was the second largest town in Moore County, with a population of 295. Once called Keyser, a phonetically unpopular name in America in the midst of a world war, the town was renamed in October 1918 in honor of Felix Addor, a local man who died on the troopship SS Leviathan — formerly the German passenger liner Vaterland, itself renamed by Woodrow Wilson — during its second Atlantic crossing delivering doughboys to the trenches.

The school was one of 16 Rosenwald schools built in Moore County. The only other documented school remaining is Southern Pines Primary. “The Rosenwald school building effort, structured as a matching grant program, began with a $25,000 gift of Julius Rosenwald [part owner of Sears, Roebuck and Company] made in 1912 to Tuskegee in support of teacher training. At the behest of Booker T. Washington and Clinton J. Calloway, Rosenwald allowed $2,800 of that money to be used in a pilot program to help communities build small rural schools,” writes Claudia Stack, a filmmaker and educator in the New Hanover Schools.

Her documentary about Rosenwald schools, Under the Kudzu, a project nine years in the making, was released in 2012. During the 20 years of the program’s existence, 4,977 schools were built in rural areas across the South and “constitute the most numerous and easily recognizable type of school built by African-American communities during the segregation era,” Stack writes. Until recently the Lincoln Park school had one of the original portraits of Rosenwald himself — a rarity in what remains of the schoolhouses. It has since been removed for safekeeping.

The building is on the National Register of Historic Places, a designation that comes with a firm handshake and hearty pat on the back — but not a penny to keep a 98-year-old wooden structure from collapsing in on itself. “After its construction in 1922 through the cooperative efforts of parents, the Moore County School Board, and the Julius Rosenwald Fund, the Lincoln Park School rapidly became the center of the African-American community located in the Keyser area,” says the registration form of the National Register of Historic Places.

Local involvement was particularly crucial. “Without a local drive to build a school, the project did not move forward,” writes Stack. “This self-help aspect of the school building projects, which bound communities tightly to their new schools, was part of the extraordinary vision shared by Rosenwald, Washington and Calloway.”

After Albert S. Gaston became the school’s first principal in 1921, “he and his wife began to raise funds for the new Lincoln Park School. They visited towns on Friday nights with a program by the school children. Their success was profound: they raised $26 at the first meeting, and at subsequent ones raised $100 dollars in 10 minutes. In total they raised a sum of $1,000,” says the National Register filing.

“I think there is something to be said for them architecturally,” says Stack of the schools. “They represent a progressive architecture. Some of the early buildings were designed by Robert Rochon Taylor, the first African-American architect to graduate MIT. He worked out of Tuskegee. Regardless, in the landscape, they’re a testament to the determination of African-American families to obtain education for their children.”

Lorine McCants, having edged into her 90s, lives a block or so away from the old wooden building where she attended school. “I went there from the first grade to the sixth grade,” says McCants. “It was wonderful. Wonderful. The only thing I didn’t like, we lived up that railroad track, and when it got cold we had to walk from up there. The teachers took care of us, and tried to warm us up the best they could. I remember one teacher. We called him Professor Gray. And Lillian Harris, she was one of the teachers. It was very important. That was the only livelihood we had. The school would have programs, different kinds of activities. It was the center of Addor.”

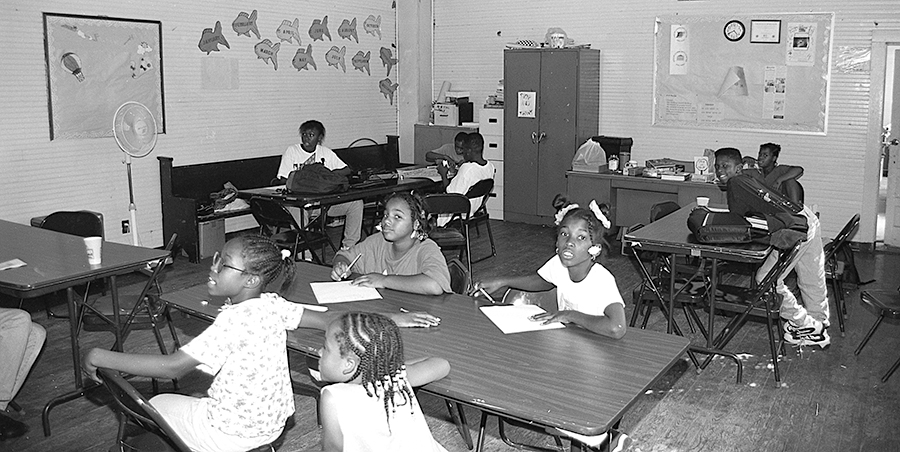

The Lincoln School was decommissioned in 1949 and became the Addor Community Center in 1952. By 2006, at the end of a series of renovations spanning decades, the building was a fully functional center with computers, a library and a kitchen. It was rental space for family reunions or worship services if one of the local churches couldn’t get its doors open.

McCants did stints at different times as both the president and the treasurer of the community center. “I worked there for I don’t know how long,” she says. “It was just my passion to help the community. I loved it.”

John Bright, who grew up in Addor and lives in Aberdeen, is the current treasurer of the Community Center Board. “It kind of came into disarray in 2008,” says Bright of the building, “and 2010 is when the center began to decline. There was no board then. It had a leak and it started to decay. In 2015 we had the community come together, and a new board was formed. Once we took it on, we saw we were facing something that was very challenging. We haven’t given up. Any way we can have an opportunity to try to sustain something for the Addor community, that’s what we want to do. I still believe there’s hope.”

By Bright’s calculations, roughly 60 percent of the homes in Addor don’t have access to city water or sewer. “The Southern Pines water facility is right there adjacent to Addor, right across U.S. 1. On the other end by the Poplar Springs Church is the Moore County sewer facility,” says Bright. “Why can’t we finish Addor out? The word says what you have done unto the least of my brothers you have done unto me, and Addor has been the least of these for a long time. We’re just trying to find a way, by the grace of God.”

Maybe that old wooden building, its cornices out of square, with the fireplaces for warmth and huge windows for light, “set with the points of the compass,” will somehow, almost miraculously, survive as an intact example of a Rosenwald Four Teacher Community School Floor Plan No. 400. “It would be wonderful if we could get it restored,” says Bright. “But the issue is, what can we do for the children and youth who are there now? Do they have 10 or 15 years to wait on the restoration of a building? What are you going to do for them in the meantime? Addor has a rich history and proud people, but the current state of Addor is not what its citizens want.”

There were 813 Rosenwald schools built in North Carolina, more than in any other state. “The way the educators and the families worked together to really push the students to a higher level of excellence, even though the schools were under-resourced, made a huge impact on North Carolina,” says Stack. “That motto of Winston-Salem State University — Enter to Learn, Depart to Serve — I’ve heard that with slight variations many times from people who attended the schools. That was really the ethic. They bettered their communities because of their experience in those small schools of that era built in black communities.”

It’s a melancholy thing when a bit of history falls into ruin, sadder yet when all that rises in its place is the faintest glimmer of hope. PS

Jim Moriarty is the senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.