True Chip Off the Old Block

Passing along the lessons of the short game

By Jim Moriarty

Like a juvenile Jeeves-in-training, 10-year-old Doug Ford Jr. carried a folding chair around Meadowbrook Country Club in the staggering July heat of the 36-hole final match of the 1955 PGA Championship. Six decades and change down the road, he might occasionally need one for himself. It would come in handy.

Doug Ford Jr. moved to Pinehurst from South Florida a few months after the passing of his father, Doug Ford Sr., in May 2018. Having had his fifth vertebrae replaced with a piece of space-age plastic a little over a year ago, Doug Jr.’s sessions sharing short game wisdom at the practice area of Seven Lakes Country Club — a lot of that wisdom having trickled down from dad — can make finding a place to sit for a spell something of a necessity. In 1955, his father may have needed it even more.

That year two future members of the World Golf Hall of Fame were in the 36-hole final of the PGA Championship, conducted at match play in those days. Dr. Cary Middlecoff, who had dispatched Tommy Bolt in the semis, was set to play Doug Ford Sr., who had been the tournament’s qualifying medalist. Ford Sr.’s father was the one who rechristened the family name from the original Fortunato. Doug Sr. matriculated in the pool halls of the Inwood section of Manhattan. “I grew up in sort of a rough neighborhood,” he once told Golf Digest. “I ran with a gang of about 10 other guys, and it was funny how we all turned out. Of the 10, six became FBI agents, and the other four went with the mob. I was the only one who didn’t end up carrying a gun as an adult.”

If the fidgety Middlecoff, who trained to be a dentist but spent less time over a patient than Steve Martin did in Little Shop of Horrors, was inarguably the slowest player on tour, Ford was just as indisputably one of the fastest. The chair was the idea of Doug Jr.’s mother, Marilyn. “She didn’t want my dad pacing and waiting to hit. That was the strategy,” he says. “When it was Middlecoff’s turn, sit down. And he did.”

Played at Meadowbrook Country Club west of Detroit, Ford squared the tight match on the 26th hole, then birdied the 29th, 30th and 32nd holes to go 3 up. “On what became the last hole,” says Ford Jr., “the pin was tucked left. Middlecoff in the morning round had missed in the bunker left. He hit it out stiff, 6 inches from the hole. In the afternoon Middlecoff is down now. Going for the pin he hits it in the same bunker and my dad says to me, ‘Dougie, there’s no way he can get it up and down twice in the same day from that bunker. I’m going to the middle of the green.’ He hits a 4-iron about 40 feet and he’s away. He putts it down to 2 or 3 inches. Middlecoff gets in the bunker, takes a swing, the ball doesn’t come out. PGA’s over with.”

Ford won his second major championship in the 1957 Masters, overtaking Sam Snead with a final round of 66 to Snead’s even par 72. At the 18th Ford plugged his approach into the face of the bunker short and left of the green. Appearing about as apprehensive as Ted Williams staring at a hanging curveball, he strolled into the bunker and holed the shot. The next year, as the defending champion, he would finish tied for second and slip the green jacket onto first-time Masters champion Arnold Palmer.

That was the year Palmer was allowed to play a provisional ball on the 12th hole, a ruling that rankled Ken Venturi (who had been playing alongside Palmer) the rest of his life. Though Venturi never let it go, Ford never took it up. At the time, Fred Hawkins, who was second with Ford, was encouraged to protest the Palmer ruling. He sought out Ford, but the response he got was that Clifford Roberts and Bobby Jones had made the decision, and that was that. Ford already had a green jacket and with it came an added responsibility to the tournament. Besides, Ford reasoned, he’d missed birdie putts on both the 17th and 18th holes that, had he holed them, would have made the entire episode nothing more than a rules footnote.

Years later, after Venturi wrote about Palmer’s plugged lie and the provisional ball, Ford was asked yet again for his opinion. “My dad just said, basically, he’d known and played with and against Arnold Palmer many years and he was an honorable man and he left it at that,” says Doug Jr.

Doug Ford Sr. was underrated as a ball-striker mostly because his short game was so profoundly admired. “The swing was three-quarter but it was very wide,” says Doug Jr. “My dad was very strong. He had great lower body motion, similar to what Hogan did. His ball-striking was never recognized as much because he was so good around the greens. He would laugh today when they talk about short-siding. He would go right at the pin, no matter what. He was so good because he had pure roll on the ball. When he would be around the green before a round, chipping, the guys would be watching him hit shots.”

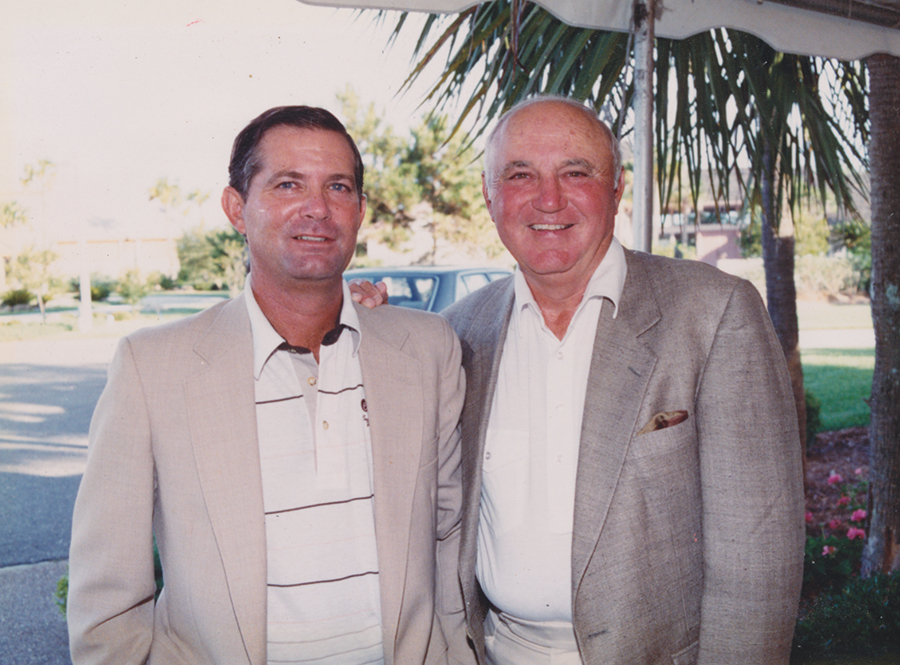

Following his one-day stint as his father’s chair Sherpa, Doug Jr. spent most of his golf life in South Florida. He played the PGA Tour briefly in the middle ’70s, prior to the all-exempt days. “I wasn’t good enough to stick out there. I was a rabbit,” he says of the Monday qualifiers days. “One year I went to the Canadian Open they had about 120 guys for four spots. That was the way it was.” He taught at Sherbrooke Golf and CC and Harder Hall Golf Resort, both in South Florida. Later, with his father and younger brother, Mike, he was part owner of Lacuna Golf Club from 1991 to 2004 in Lake Worth. After that he taught at Deer Creek Golf Club in Deerfield Beach before moving to Pinehurst. Doug’s brother owns Jack O’Lantern Resort and Golf Course in Woodstock, New Hampshire, and his son, Scott, is also a golf pro.

After back surgery and hip replacement, Ford pretty much confines his teaching to the short game. And if you don’t think the knowledge of the father can be passed to the son, here are two words to remember: Butch Harmon. If you have trouble convincing yourself that there isn’t much to learn from someone who has a cane in their hand from time to time, try Googling pictures of Harvey Penick. “What I learned from my dad, just watching and playing, was club selection,” says Doug Jr. “You don’t always grab the sand iron when you miss the green. He believed in not changing the swinging motion but changing the club to fit the shot. The more green you have to work with, the less loft you use. You want to get the ball on the green and get it rolling. As far as the execution of the shot, you’ve got a short shot so you shorten the grip on the club. You have to get in position so your body is still. Things like that. Obviously, everybody’s a little different.”

Almost any teacher will tell almost any golfer that the quickest route to better scores is through the art of the short game, Ford’s specialty. “I’m going to give it a shot,” he says. “See if I can develop a clientele.” PS

Jim Moriarty is PineStraw’s Senior Editor and a former writer for Golf Digest.