After the Barns

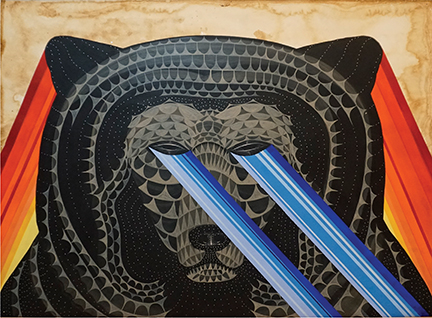

The art of David Ellis

By Jim Moriarty

The painted barns of Cameron are mostly overgrown, tumbled-down boxes — tar paper and old boards defying gravity by the grace of a rusty nail. In some cases, it seems as though all that’s holding them up is the paint. Well, the paint and the idea that made them something more than old barns outside a tiny town that grew up over a century ago at the end of an ancient railroad. Twenty years have passed since David Ellis gathered up a bunch of his friends, artists from New York to Tokyo, to come to his hometown to do what they do, make art. Described in those days as a “street artist,” Ellis brought Brooklyn and the Bronx to the barns Earl and Juanita Harbour offered up as canvases.

“There were two massive trips with like 30 people each time, and then there were several trips when it would be me and a couple of people,” says Ellis of the group that became known as the Barnstormers. He’s sitting at the kitchen counter in his small Brooklyn apartment, having a toasted bagel for breakfast. Fresh paintings lean against the wall behind him. His architect wife, Kouki Mojadidi, tends to the plants on the porch. He’s working on his next one-man show, still two years over the horizon.

When Ellis talks, he looks off to the side, not because the answer’s out there, but because that’s where he sees all the questions. He’s interested in the questions.

“A lot of those barns we kind of patched up a bit. The roofs were blowing off. There were vines covering them. Oftentimes, there’s a sweet spot. The vines start to overtake something. It fades, it peels. It’s like the patina of time itself. It may be faster on the exterior of a weathered barn, but the fact of the matter is all of this fades — every bit of it — even in the most climate-controlled space. The elements will take it all at some point. Might be a thousand years, might be a 100 years.”

Significant as it was in the moment, what Ellis left behind in Cameron turns out to be far less than what he took with him. “When I do return to Cameron, when I did paint those barns, there’s a cadence and a spirit in the people from Cameron that’s a big part of me,” says Ellis. “It’s who I am. It folds into everything I do and everywhere I go. Cameron people are special people. Real soulful people.”

Ellis and his younger brother, John, are the sons of a Presbyterian minister, Stewart, and his wife, Grace. Stewart nurtured the flock in a small town church. Grace nurtured the art. David has had solo exhibitions in places as far-flung as Texas, California, New York, New Zealand, Ohio, Japan. Two of his pieces have been on display in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The main gallery representing him is Joshua Liner Gallery in New York, but his work can be found in London, Paris and L.A., too.

John is a musician who also lives in New York. His main instrument is the tenor saxophone, and he has appeared with Ellis Marsalis, Charlie Hunter, Dr. Lonnie Smith, Kendrick Scott Oracle, Helen Sung and Lionel Loueke, among others. With all due respect to N.C. 24/27, there are apparently two roads leading out of Cameron: professional wrestling (Shannon Moore, the Prince of Punk; Trevor Lee, the 2017 Impact X Division Champion; and the Hardy Boyz, Matt and Jeff); and art.

In Cameron, a boy’s rite of passage included time in the tobacco fields. “I must have been like 12, 13, 14 — that age,” says David Ellis. “Two or three summers. It was tough but you really appreciated getting to the end of the row. I think the reward was a Pepsi and a little pack of Nabs. You’re just so drained and you’re covered in the resin that sort of seeps out of the little hairs on the leaves. It really cuts through your skin. You take Dramamine and that kind of helps with the sickness you get. I got so sick my last summer, I couldn’t do it anymore. But I love that smell. When it’s curing in the barns, when it turns that golden brown and they truck it through town, that smell that permeates the air is just one of my favorite smells in the world.”

Ellis incorporated more than the barns into his art. He took the tobacco with him, too, using it to prepare the paper he drew and painted on. “I brought back like a whole burlap sheet of tobacco from Cameron on one of those barn trips. I used that for years to stain the paper,” he says. “I’d lay a whole floor of paper out with as many sheets as I could fit in the footprint of the studio. I’d brush and pour the stain on and let it evaporate overnight, really soak in. These amazing pools and forms would show up the next day. They’re not so much backgrounds as they are foundations. I like having something to react to, to riff against. It activates different memories. Just the smell I remember growing up — that time period, 13, 14, when you really start to find the impulses you chase your whole life.”

When Ellis couldn’t stomach priming tobacco anymore, he turned to Earl Harbour’s car wash, where the hiss of soapy water and the flapping of soft brushes danced to hip hop tunes. He’d stay up late with the volume turned down to listen to DJ Gilbert Baez on D103 FM out of Fort Bragg. The whole notion of percussion, beat, rhythm, seeped into his work as deeply as a day in the fields. He talks about his love of music in a statement on his website, davidellisstudio.

“The first nine months of your development you were listening to one of the best bass drums in the world until yours kicked in with it and you heard the best polyrhythms ever . . . I think everybody’s got a lot of music in ’em. I think that’s why you find marching bands and percussion in every form in every corner of the planet.”

That music, those rhythms, melded with one of his earliest childhood memories to form another of Ellis’ expressions, his kinetic sculptures. “Maybe I was 3,” he says, just months before his family moved to Cameron. “I remember seeing this piano play by itself.” The player piano was at an uncle’s house in Raleigh, the home of another jazz enthusiast. “It really went back to trying to figure out how these things work. I went online and I found all these discussion boards for people who restore these things. I made all the machines and bellows and stuff from scratch.”

The sculptures are collections of everyday objects, paint cans, empty bottles, stuff. View them here. Using a scroll, almost identical to the one in a player piano, he pulls tones and rhythms from the sculpture. “A painting, essentially, is a drum. It’s a membrane stretched over a frame. We think of them for the visual resonance but when you’re preparing a panel you often tap it. The under layers of rabbit skin glue dries, it tightens up the pores of the canvas, and you get a drum sound. And I wanted to go more in the sonic direction.” Examples like The Message, True Value and Trash Talk — some done in collaboration with Roberto Lange — can be viewed on his website.

Not long after abandoning the car wash, at 16 Ellis was off to the North Carolina School of the Arts. “It was clear to me and to everyone around me at a very young age that I was totally absorbed in making things. I didn’t have a lot of patience for a lot of things, but making things, painting things, drawing things, sculpting things — I’d just spend days on them,” Ellis says.

“I think you would call him a prodigy,” John Ellis says of his older brother. “He might resist that characterization, but it’s certainly what it seems like to me.” John, in fact, followed David to the School of the Arts, where both brothers blossomed.

“In terms of formal education I’d say maybe that school added the most fuel to what I was already working with,” says David. “The dean of the art school was Clyde Fowler. He was the drawing teacher, but the drawing class was way more than just drawing. He was showing us film and painting techniques. He just blew everybody’s mind. If you wanted to have your mind blown, it was blown. He passed away not to long ago. He helped a lot of people with their dreams.”

With their boys at the School of Arts, the parents moved to Winston-Salem. Stewart, now retired, aligned with Trinity Presbyterian Church there, and Grace wrote poetry (Sam Ragan published some of her work in The Pilot in their Moore County days) and plays, something she’d begun doing in Cameron when she penned Through the Depot Door to celebrate Cameron’s centennial. She’s been a member of Greensboro’s Playwright’s Forum for more than 20 years and has started a group called the Triad Playwright’s Theater, which recently performed one of her works, Rhonda’s Rites of Passage. David Ellis finished his formal education in New York at the School of Visual Arts and then The Cooper Union.

Though the Barnstormers took on something of a life of their own, there aren’t any card-carrying members. It was never meant to be a “thing,” a traveling carnival of artists. There have been projects since Cameron, but they’ve been few. In 2004 a group of them came together to do a project for the Southeast Center for Contemporary Art in Winston-Salem.

“We took one of the Harbours barns apart piece by piece, put it on a flatbed, drove it to Winston, rebuilt it in the museum and we shot time lapse (video) of it coming down and coming back up,” says Ellis. “Over the course of two months we’d fly artists down from New York, Tokyo, some other places, to paint the barn. That was filmed. Then the next person would come in and paint over that thing. That was filmed. Then we took the barn apart and put it back up in Cameron and covered it with tar paper.”

There was one other Barnstormer family reunion, at the Joshua Linear Gallery — a Barnstormers version of The Band’s The Last Waltz. “It was never really meant to be all that formal,” says Ellis of the group. If an invitation for another collaborative project was to come down the road, Ellis isn’t even sure he’d want to call it Barnstormers “out of respect for what we’ve all done together.”

The kind of time-lapse painting he brought to Winston-Salem is another of his core expressions, what he calls his motion paintings. They can be viewed here. “It was a way for me to look back and be like, ‘Oh, man, I wish I’d stopped there,’ or ‘It’s interesting I changed that.’ And then it became this fluid, creation, destruction, creation, destruction sort of moment. It wasn’t, for me, about a start-to-finish thing. It was about this thing is constantly changing. I still return to that. I think it taps into the improvisational kind of music side of the brain. I go back to that Tibetan idea that no condition is permanent. Like the mandalas that are painted with sand, then the wind blows them away and you make it again.”

Walter Robinson, an editor of Artnet Magazine, wrote, “Whatever Ellis makes in one moment is erased in the next. What was just done is gone before you can even see what it is. The stop-action is mesmerizing and magical but at the same time it’s no mystery, anyone can see how it’s done, just pictures, pictures, pictures, painted one after the other step by step. But it adds up to a perfect art film . . . .” It was one of his motion paintings, this time of a moving van in Osaka, Japan, that found its way to MOMA. Some of his motion paintings, sometimes solo, sometimes in collaboration, can be viewed on his website, as well.

When the Barnstormers were in Cameron doing what they do best, Cameron did what it does best — it threw a pig pickin’. “You get one artist making something, there’s a lot of energy generated,” says Ellis. “You get like 20, 30 artists all working in a compressed amount of time with a community where it’s a little bit out of the ordinary for that to happen, the energy that was generated between the artists and the people of Cameron, that was amazing. The feedback we had, the sitting down and having a pig pickin’ covered in paint. . . it was electric.”

It was the sweet spot. PS

Jim Moriarty is senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.

The kitchen garden

September Pears

Yard decoration or just plain delicious

By Jan Leitschuh

Tough to grow on a commercial basis, local Sandhills homeowners can still enjoy home-grown pears and spring bloom in their landscapes.

Now is the harvest season for pears, so get ready to enjoy this sweet fall fruit, whether you’ve grown it or purchased it at the grocery as prices drop.

The cute little “Honeysweet” pear tree I planted six years ago has at least half a dozen little pears on it this year. Way to amortize a $50 investment, eh? That’s about $6 a pear, this year.

In the Honeysweet’s defense, it has borne a few good fruits in the last few years, and is planted in a very hot, dry and sandy section of the property — so props for even surviving, much less bearing sweet little treats. It adds pretty spring blossoms to our edible landscape and keeps a trim size, so the sweet treats are a bonus. Let’s see your crabapple or dogwood do all that.

In North Carolina, pears are not a big commercial crop, mostly due to the disease called “fire blight,” a bacterial withering many pear varieties are susceptible to. The affected young tips look as if they were blasted with a flame-thrower. The browned ends curl into a characteristic “shepherd’s hook” shape. If you do find fresh pears at roadside stands, it will likely be more toward the mountains in apple-growing areas.

But a homeowner without a financial stake can plant a decorative, blight-resistant tree or two and reap the benefits in good years, as well as enjoy the lovely spring bloom.

The other pear issue is their tendency to bloom early and get whacked by a late hard frost. This is a disaster for a commercial operation, but a homeowner can toss a quilt over a small tree, or find other temporary means to keep the cold night temperatures at bay, removing the covers in the morning so the bees can pollinate the blossoms.

Pears are one of the world’s best known and favored fruits. And while a homeowner can plant a pear tree or two for successful fun — our Southern Pines neighbor has a very prolific bearer — the good news is that the supermarkets are full of the seasonal fruit right now, and for the next few months.

My husband and I love to combine two fruits that peak about now. Come the end of August and into September we love to pick our backyard figs and simmer them with pears and a little lemon juice into a delectable pear/fig sauce we then freeze in little tubs and serve all fall with pork chops, or on sweet potatoes. The leftover pears go into salads with different creamy cheeses, or into a pear crumble.

So even if the little Honeysweet fails, we have plenty of backup for our favorite annual fruit sauce, fresh eating, pear tarts and salads — and so do you. Beautiful varieties such as Anjou (red and green), Bosc (an artistic tan), Seckel (the “sugar” pear), Bartlett, Comice and more — your favorite market will have them on special this month as the harvests in California and the Northwest come in.

Let’s say you want to try your hand at a little edible landscaping. Your best bet is to plant a fire blight-resistant variety. There are several. The old Kieffer variety gives a pretty reliable harvest. (I’ve noticed several homes in the Sandhills with Kieffer pear trees.) The fruit is a bit coarse, and not the smooth quality of the highly fire blight-susceptible Bartlett, but I’ve eaten it fresh and it makes a great pear/fig sauce, as well as jams, preserves and canning. Also look for newer, more blight-tolerant varieties such as Moonglow and Magness. The teeny but quite delicious Seckel variety is also somewhat fire blight resistant and puts out lots of fruits, ripening in late August.

New varieties are being released and might be worth an experiment. Some North Carolina folks give up on conventional pears and plant the fairly blight-resistant Asian pear, enjoying its unusual apple-like crunch. You can buy these in stores now, too, to decide if you like them.

Luckily, the Sandhills has a few pluses for kitchen-garden pear production, even if our humidity and dew encourage fire blight. Cold air flows downhill, so a higher Sandhills site might offer better frost protection and airflow than at the bottom of a slope. Our deep sandy soils make the pear’s vigorous root system happy. They don’t like a tight clay. Like apples, they detest “wet feet,” poorly drained sites. Plant your tree in November and water well. Don’t use fertilizer in the hole, as it will burn roots.

High nitrogen fertilizers are also a no-no, since that encourages rapid growth of the juicy green new growth so susceptible to fire blight. Simple compost or a low nitrogen fertilizer should do the trick. Google fire blight to recognize the browned tips, and prune them off well into healthy tissue, dipping your clippers in alcohol after each cut to avoid spreading the bacteria. Also, keep the weed eater away from the sprouts that form at the base of a pear — prune those in winter. Follow simple shaping advice. It’s easy to find it online. Whatever you do, don’t whack your tree back to prune it. The vigorous root system will send up useless, vertical shoots from every branch. Prune judiciously.

Pear-picking timing is a little different from many fruit harvests. Pears should be harvested when fully formed, but not ripe. If you have a tree with fruit, start looking closely in early August.

When to actually pick a pear takes some trial and error. The size and shape should look like a ripe pear, and the pear’s color should have a slight yellow undertone. The squeezing texture morphs slightly from rock-hard to just firm, and it should pick easily, twisting off. Don’t be afraid to pick a few to experiment with and make a mistake because the changes are subtle.

After picking, refrigerate your pears for a couple of days. You can also hold them for a while at this stage in the vegetable crisper of your fridge. To ripen them, remove and let stand four or five days at room temperature. Once you have a feel for your particular variety, you can chill pears and ripen them at your convenience.

Or, get thee to a supermarket pear special

this month.

Fall Balsamic Pear Salad with Walnuts and Gorgonzola

Balsamic Vinaigrette:

1/3 cup extra virgin olive oil

2 1/2 tablespoons balsamic vinegar

1 tablespoon honey

1 teaspoon Dijon mustard

1 1/2 tablespoons finely diced shallot

Salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste.

Salad:

2 pears, ripe, sliced thin

Lettuce/spinach blend

1/2 cup chopped walnuts (candied optional)

2 ounces Gorgonzola or other blue cheese, crumbled

(Optional: sprinkling of dried sweetened cherries or cranberries)

Whisk up the dressing. Slice ripe pears shortly before serving to avoid browning. Layer salad and pears. Top with walnuts, cheese and more pears (and dried fruit, if desired). Drizzle with dressing just before serving. PS

Jan Leitschuh is a local gardener, avid eater of fresh produce and co-founder of the Sandhills Farm to Table cooperative.

Golftown Journal

Down Highway

A gem sparkles in Aiken

By Lee Pace

Before Henry Flagler laid the first railroad tie or built the first ornate hotel room in South Florida, before James Walker Tufts scraped his first rudimentary golf hole out of the sandy loam around Pinehurst, there was Aiken, South Carolina, a small town built on a plain just 15 miles from Augusta, Georgia, and along a key intercontinental railroad stop connecting the major cities of the East to New Orleans.

At first they came in the summertime just after the Civil War from Charleston and surrounds to escape the threats of malaria and yellow fever. Then in the 1880s it became all about the horses — riding, breeding, playing polo, running steeplechases. Streets were named Ruffian and Saratoga. The clay-based soil was ideal for horses’ hooves and traction, the winter temperatures were mild, and the area’s mineral springs thought to be health-giving. There were tennis courts and ample wild game roaming the woods. The Vanderbilts, Goodyears, Appletons, Pinkertons, Graces and Astors wintered there. Kings and presidents visited.

Aiken was Palm Beach before there was a Palm Beach.

Golf followed as well, first at Palmetto Golf Club in 1892 with a four-hole course that expanded to a regulation 18 by 1895; and then at Highland Park Golf Club in 1912, that course built as an amenity to a new hotel and residential community that has an interesting connection to the Tufts family, Donald Ross and Pinehurst.

Pinehurst, Camden and Aiken shared the common heritage of being perfectly located circa 1900 to offer warmer winter weather within one day’s train ride from New York, Philadelphia, Boston and other northern climes. This was before Florida had evolved and certainly long before the advent of commercial air traffic. The train coming from the north passed through Raleigh, went to Southern Pines, and from there it was 90 miles to Camden and another 80 to Aiken.

The Kirkwood Hotel was located in Camden next to the train station and was a 200-room facility that boasted among its amenities in 1903 a nine-hole golf course. Walter Travis, a three-time U.S. Amateur champion who dabbled in course design in the early 1900s, redesigned the original course, and then Ross visited in 1938 to reconfigure the layout known today as Camden Country Club and convert the greens from sand to grass.

“Camden is one of the special places in the Carolinas,” says Charleston’s Frank Ford III, an accomplished Charleston golfer with multiple championships on state and regional levels. “I’ve had a love affair with that golf course since the first time I saw it. It’s just so much harder than it looks.”

Following James Tufts’ death in 1902, Leonard Tufts took over the operation of the village of Pinehurst. He knew that beyond the resort amenities themselves, convenient accessibility was paramount to being successful in the travel business. The planning, construction and maintenance of good highways became an interest and priority of Tufts, who led the resort until his retirement in 1929, when he turned the reins over to son Richard.

Leonard was the moving force in building what became Midland Road, connecting the train station in Southern Pines to Pinehurst. At various junctures he would serve as president of the Capital Highway Association and the U.S. Good Roads Association. He was also chairman of the Moore County Good Roads Committee.

The Atlantic Highway was part of the original National Highways Association created by the federal government in 1911 to create and maintain some 50,000 miles of public highways. The Atlantic linked Maine to Miami and was the precursor to U.S. Highway 1. The road ran from the north through Southern Pines and turned southwest toward Camden, Aiken and Augusta before veering south toward Savannah.

Tufts by virtue of his perch on these important highway boards could see where opportunities lie. And one area of exploration he thought was to have a series of resort hotels along this key highway running into South Carolina.

A group of Aiken businessmen in 1912 launched a company to build a hotel, golf club and real estate project on the site of the original Highland Park Hotel, a grand destination with 125 rooms operating from the late 1860s until burning down in 1898. They did so with some unknown degree of consultation, encouragement and perhaps even financial investment from Tufts. The course opened with 11 holes in 1912 and expanded to 18 three years later as Highland Park Golf Club, and remains in business today as Aiken Golf Club.

“Building hotels and golf courses along Highway 1 was big business in the early 1900s,” says course owner Jim McNair Jr., who inherited the course from his father and personally led a restoration and rebuilding effort in the late 1990s. “We found old newspaper stories talking about Leonard Tufts visiting and helping put a deal together. At the time, no one thought the South was good for anything but resorts — getting people down from the North out of the cold.”

Donald Ross by 1910 was devoting his time almost exclusively to designing golf courses across the eastern United States and apparently was going to route and build the course at Aiken. But his schedule was too jammed, so a fellow Scottish golf pro who had immigrated to the United States named John Inglis did the work with input from Ross. The fortunes of the Highland Park Hotel and its golf course followed that of many enterprises in the Roaring ’20s — success out of the gate and then a devastating collapse in the early 1930s. The town of Aiken eventually took the property over, tore down the hotel and sold the golf course to Jim McNair, a top amateur golfer of the mid-1900s and winner of the Carolinas Amateur in 1946 and ’48.

McNair Jr. took the operation over in 1986 following his father’s retirement and spent a decade noodling ideas of how to improve the facility and bring back some of the early design features from Inglis and Ross. He pursued Bill Coore and Ben Crenshaw in the mid-1990s to visit the course and consider a restoration job, and Coore looked at the course in 1997 when in town to visit Palmetto Golf Club, which sits just a mile and a half away. McNair took Coore’s advice and suggestions to renovate the course “in-house,” and over two years, McNair and his crew removed some 10,000 trees, rebuilt the greens, put in a new irrigation system, and crafted some broad swaths of sand and assorted vegetation.

“We’ve got more than a century of tradition and have a fun, accessible golf course,” McNair says of his daily fee operation. “But we’re still not the oldest club in town.”

Today AGC is a terrific experience with a $27 weekend green fee, its 5,800-yard, par-70 measurements belying the challenge of hitting off uneven lies all day and navigating the small and quirky greens (there is even a links-style double green for the first and 17th holes) and the twists and turns through the surrounding neighborhood. It’s on the National Register of Historic Places and is replete with stories like the stone and grass staircase leading from the tee of the par-3 16th down to the green. The curious dimensions of the staircase — requiring at least one or two extra steps at each level before going down the next riser — prompted dancing virtuoso Fred Astaire to navigate them with a makeshift tap dance when he played there during the winter entertainment season.

The evolution of Florida in the first half of the 1900s certainly changed the winter resort business in the South. But fortunately both Palmetto and Aiken Golf Club have survived all manner of economic and wartime obstacles and remain viable today, each with its own niche in a golf-rich environment that includes the shadow of Augusta National down Interstate 20 and another ultra-private club just outside of Aiken, the Tom Fazio-designed Sage Valley.

Less than a quarter of a mile to the east of the first tee of Aiken Golf Club is U.S. Highway 1, and tracing the left side of the first five holes is the railroad, keeping the Pinehurst-Camden-Aiken connection viable today. PS

Lee Pace’s adventures exploring many of the interesting old golf courses of the Carolinas will be included in a forthcoming book from UNC Press, Good Walks—Strolling Across the Carolinas Golf Landscape, due out in 2020.

Bookshelf

September Books

FICTION

The Edge of America, by Jon Sealy

As chief financial officer for a Miami holding company and CIA front, Bobby West is on the edge. In the go-go ’80s financial culture, he’s over-leveraged his business and turned to a deal-with-the-devil money laundering operation with a local gangster in the high-stakes world of South Florida’s drug culture. When the operation goes south and $3 million goes missing, West must reckon with the fallout. With echoes of Iran-Contra and the Orwellian surveillance state, The Edge of America is a stunning thriller about greed, power and the limits of the American dream.

The Dutch House, by Ann Patchett

Once upon a time, there was a house, an impossibly lavish house, in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania. Generations of two families would come and go, but there would always be the house. The Dutch House. Cyril Conroy was a man with a vision following WWII, buying and selling real estate. He bought the house and all the belongings of the former family as a surprise for his young wife. Unfortunately, the house and the lifestyle were too ostentatious for her, so she fled, entering a life of nun-like service while leaving her husband and two small children behind. The story skillfully navigates back and forth in time through the honest and, often humorous, voice of the son, Danny, who was primarily raised by his steadfast older sister, Maeve, and the household staff. Life changes drastically the day their father introduces a conniving young stepmother and her two daughters. Through love, loyalty, loss, treachery and wit, Patchett spins a tale impossible to put down.

The Water Dancer, by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Tobacco has finally leeched the lands of the Virginia plantations, and the “Quality” people are facing desperate times, leading them to even more horrific acts upon their “Tasked.” Hiram Walker is a young slave whose voice rises from the pages. His father is his owner, his mother a slave. Early on, it becomes apparent that he has certain abilities and even powers of “Conduction,” which lend a fantastical element to the story. These strengths will serve Hiram well as he enters the world of the Underground, joining Harriet Tubman and countless others in the quest to free all those entrapped in the maw of slavery. A powerful story by the essayist and literary force behind The Black Panther, the words that pour from Coates are pure magic. The Water Dancer is nothing short of brilliant.

Cold Storage, by David Koepp

Meet Cordyceps Novus, a highly adaptable fungus that wants just one thing, to take over the world. After being contained underground for 40 years, conditions are finally perfect for a comeback. Several floors above, two young night-shift security guards decide to track down the source of the mysterious alarm below. Koepp’s debut novel is both terrifying and humorous, a thrilling combination. After getting an inside look at the growth and spread of this fungus, you might never look at a mushroom the same way again.

This Tender Land, by William Kent Krueger

In Minnesota in 1932, the Lincoln School is a pitiless place where hundreds of Native American children, forcibly separated from their parents, are sent to be educated. It is also home to an orphan named Odie O’Banion, a lively boy whose exploits earn him the superintendent’s wrath. Forced to flee, he and his brother Albert, along with their best friend, Mose, and a brokenhearted little girl named Emmy, steal away in a canoe, heading for the mighty Mississippi and a place to call their own.

The Testaments, by Margaret Atwood

When the van door slammed on Offred’s future at the end of The Handmaid’s Tale, readers had no way of telling what lay ahead for her — freedom, prison or death. With The Testaments, the wait is over. Atwood’s sequel picks up the story 15 years after Offred stepped into the unknown, with the explosive testaments of three female narrators from Gilead. “Dear Readers: Everything you’ve ever asked me about Gilead and its inner workings is the inspiration for this book. Well, almost everything! The other inspiration is the world we’ve been living in,” writes Atwood.

NONFICTION

Yale Needs Women: How The First Group of Girls Rewrote the Rules of an Ivy League Giant,

by Anne Gardiner Perkins

The experience the first undergraduate women found when they stepped onto Yale’s imposing campus was not the same one their male peers enjoyed. Isolated from one another, singled out as oddities and sexual objects, and barred from many of the privileges an elite education was supposed to offer, many of the first girls found themselves immersed in an overwhelmingly male culture they were unprepared to face. Yale Needs Women is the story of how these young women fought against the backward-leaning traditions of a centuries-old institution and created the opportunities that would carry them into the future. Perkins’ unflinching account of a group of young women striving for change is an inspiring story of strength, resilience and courage that resonates today.

Talking to Strangers: What We Should Know about the People We Don’t Know, by Malcolm Gladwell

The host of the podcast Revisionist History and best-selling author of The Tipping Point, Blink, Outliers, What the Dog Saw and David and Goliath, offers a powerful examination of our interactions with strangers — and why they often go wrong. Talking to Strangers is a classically Gladwellian intellectual adventure, a challenging and controversial excursion through history, psychology and scandals taken straight from the news. He revisits the deceptions of Bernie Madoff, the trial of Amanda Knox, the suicide of Sylvia Plath, the Jerry Sandusky pedophilia scandal at Penn State University, and the death of Sandra Bland — throwing our understanding of these and other stories into doubt. Something is very wrong, Gladwell argues, with the tools and strategies we use to make sense of people we don’t know. And because we don’t know how to talk to strangers, we are inviting conflict and misunderstanding in ways that have a profound effect on our lives and our world. In his first book since David and Goliath, Gladwell has written a gripping guidebook for troubled times.

How to Raise a Reader, by Pamela Paul and Maria Russo

An indispensable guide to welcoming children — from babies to teens — to a lifelong love of reading, written by two editors of The New York Times Book Review. Combining clear, practical advice with inspiration, wisdom, tips and curated reading lists, How to Raise a Reader shows you how to instill the joy and time-stopping pleasure of reading. Divided into four sections, from baby through teen, each section illustrated by a different artist, this book offers something useful on every page, whether it’s how to develop rituals around reading or build a family library, or ways to engage a reluctant reader. A fifth section, “More Books to Love: By Theme and Reading Level,” is chockfull of expert recommendations.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

I Love My Glam-Ma,

by Samantha Berger

Why would anyone want a plain old Grandma, when they could have a Glam-Ma! From fort building to rocking and rolling to hosting the event of the season, there’s not much a Glam-Ma cannot do. Celebrate Grandparents Day Sunday, Sept. 8. (Ages 3-6.)

Stormy: A Story About Finding a Forever Home, by Guojing

Readers (and non-readers) of all ages will fall in love with this stunning picture book that explores trust, patience and kindness through the eyes of a lonely young woman and a homeless dog. This little book is sure to be a big hit with animal lovers everywhere. (Ages 3-6.)

Stay, by Bobbie Pyron

“Everyone loves a good story, especially one with a dog in it,” says Piper Trudeau’s mom as Piper steps on stage at school to share the story of Jewel, a homeless woman, her dog, Baby, and their incredibly difficult situation. The author of A Dog’s Way Home and A Pup Called Trouble brings a captivating story of hope, determination and just plain compassion that is just perfect for animal-loving middle-schoolers. (Ages 8-12.)

Last Kids on Earth and the Midnight Blade, by Max Brallier and Douglas Holgate

Zombies! Monsters! Adventure! Laughs! The Last Kids on Earth series has it all and it comes to life Saturday, Sept. 21, at 2 p.m., when author Max Brallier brings his tricked-out Last Kids on Earth truck to The Country Bookshop. This free event will feature the fifth book in the New York Times best-selling series about a group of kids who defend themselves and their treehouse against the monster apocalypse. The book is available beginning Sept. 17. (Ages 9-13) PS

Compiled by Kimberly Daniels Taws and Angie Tally