By Romey Petite

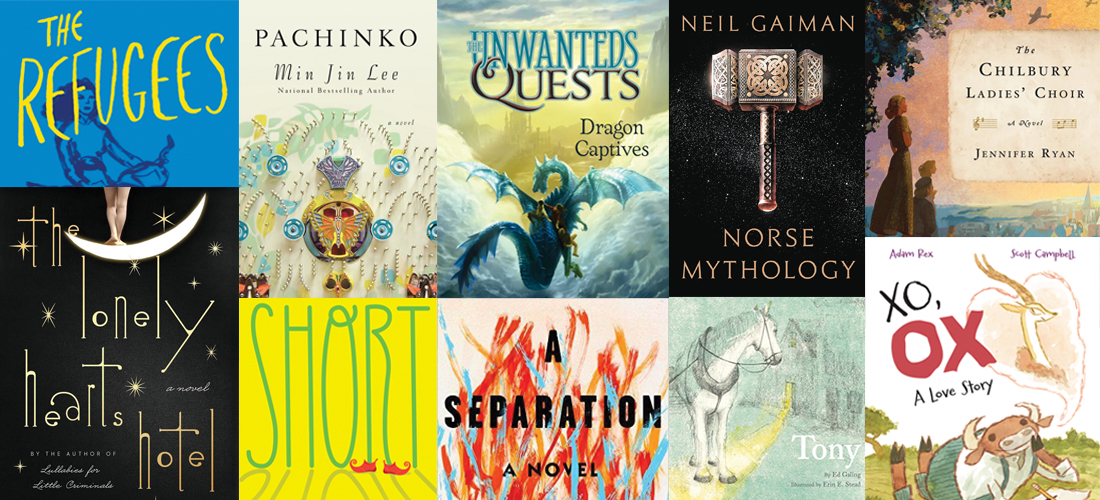

Norse Mythology, by Neil Gaiman

The Norse pantheon has never received equal love in America as say, Edith Hamilton’s compendium of the Greek myths or the fairy tales compiled long ago by the Brothers Grimm. How fortunate then that these Scandinavian epics have New York Times best-selling and treasured storyteller Neil Gaiman, who now tasks himself with retellings from the few myths that have survived the test of time. In doing so, Gaiman has created a singularly comprehensive volume for readers both young and old while recounting these obscure stories with an evident deep, formative love (he’s oft-referenced them both in his award-winning Sandman series and his Hugo and Nebula winning American Gods). In the hands of the author’s capable, beloved and familiar voice, curl up by the hearth-fire with Norse Mythology and read of the war between the Aesir vs. the Vanir, the strange self-sacrifice of Odin, the misadventures of thundering Thor, wits of the wily Loki, and the battle at world’s end to come in Ragnarok.

The Lonely Hearts Hotel, by Heather O’Neill

The year is 1910, the setting: a Catholic orphanage in Montreal. This locus becomes the meet cute of two talented prodigies, Pierrot, a virtuoso vaudevillian with a Chaplinesque flair, and Rose, a talented terpsichorean known to break out into her own oddball improvised routines. As Anna Freud said, “Creative minds have always been known to survive any kind of bad training.” The Lonely Hearts Hotel is the tale of two such souls that manages to be, all at once, whimsical, tragic and ribald. Despite nearly succumbing to the fierce Canadian cold, regular thrashings and questionable punishments from the orphanage’s nuns, these two souls cannot be kept apart, nor will their spirits be broken. Fans of Erin Morgenstern’s The Night Circus and the works of Michael Chabon will instantly fall for O’Neill’s charm, flowery language, use of metaphor and vignette-like chapters.

A Separation, by Katie Kitamura

A young woman and her husband, the unfaithful Christopher, make the responsible decision to go separate ways after acknowledging their irreconcilable differences. Prior to the formal divorce and the signing of any legal documents, the couple take a sojourn from each other, if only to delay the inevitable. When the woman receives news that Christopher has gone missing sometime during his research trip in Greece, she finds herself impelled by the mystery of his disappearance. Leaving the comfort of her new lover’s arms, she travels abroad to the remote region of Peloponnese in an effort find her estranged husband. The voice Kitamura employs is detached, sparse, direct, divulging analytical details in an almost clinical way, but still subjective. Appropriately, A Separation is a novel of the nature of secrets, intimacy, and how an abundance of the former can affect relationships.

Shadowbahn, by Steve Erickson

Invoking the lucid dream style of the American road trip novel with a touch of the absurd, Shadowbahn tells of a near future in which icons thought forever lost will reappear, just as a memory can — without warning. In this case, the Twin Towers make an unannounced return in the middle of the South Dakota badlands. This cleverly dubbed “American Stonehenge” begins drawing scores and scores of people to marvel at the sight and pay vigil. Like any inexplicable phenomenon, there are those that come to revere this spontaneous apparition. Meanwhile, Elvis’ stillborn (and little known) brother awakes, possessing a fragmented mirror of his brother’s memories driving him half mad. In keeping with this theme of doubles, two siblings, Parker and Zema, travel together through this territory on their way to visit their mother in Michigan. Despite its experimental nature — Erickson’s prose is part poetry — it’s delightful to read and puts one in mind of Ron Currie Jr.’s Flimsy Little Plastic Miracles. Readers will slowly piece together this dreamlike dystopia a page at a time as though sampling snippets of micro-fiction.

The Refugees, by Viet Thanh Nguyen

The Pulitzer-winning author of the recent New York Times best-seller The Sympathizer debuts a collection of short stories compiled over a span of 20 years. This long-awaited result is a series of unique purgative experiences of the consequences when long-suppressed memories resurface. In the eponymous tale, for example, a ghostwriter is visited by a ghost of her own — the incorporeal kind. Such spirits are mere shadows — never so malevolent as they are imagined to be. Under Nguyen’s scintillating eye and keen ear for chilling detail, readers experience exorcisms and learn lives left behind are never so far away — though they may take some time in the remembering.

The Book of American Martyrs, by Joyce Carol Oates

Tragedy strikes as a tiny town becomes host to an act of senseless, yet calculating, violence when aspiring martyr Luther Dunphy decides to shoot Augustus Voorhees, a doctor at an abortion clinic. The event becomes the catalyst throwing the respective families, the surrounding community and the nation as a whole into turmoil. Still, Oates paints thorough portrait-like narratives of these two men — managing to transmute them into far more than simple stock characters of murderer and victim. Like a body snatcher climbing behind the face and peering through the eyes of each of these men, the author displays her shocking versatility as she weaves from language of the fanatic to the analytical fishbowl lens of the doctor. Beginning in 1999, recent tragedies have only made this gripping story all the more relevant.

The Chilbury Ladies’ Choir, by Jennifer Ryan

Whisk yourself back to 1940 in Ryan’s debut historical novel. The Chilbury folk have just received the tragic news of their first local loss in the casualties to come — the only son of the Winthrop family. While it’s true he wasn’t exactly well-liked, it only adds insult to injury, as the war has taken another toll on the town: swept away the tenor, bass and baritone sections entirely from the local choir. The vicar doesn’t find the five remaining member’s half-hearted performance terribly promising. Things look grim until Miss Primrose “Prim” Trent, an eccentric music teacher, arrives, managing to reassemble them into the eponymous women’s choir. Inspired by her grandmother’s stories of growing up in a tiny village in Kent, Ryan’s novel is told through epistolary musings — the scathing wit of journal entries and letters written by of Edwina, Venetia, Mrs. Tillings, Silvie (a Jewish refugee from what was then Czechoslovakia) and other local characters that come to life under the author’s pen. Fans of Hannah Kristen’s The Nightingale will want to watch out for this one.

Pachinko, by Min Jin Lee

Told in fluid prose, Pachinko charts a course from the 1930s onward. In Korea, as a young girl, Sunja, the only hope for a poor family, is abandoned by her lover, Hansu, when he receives word she is pregnant with his child. Fearing the disgrace of life as his mistress, Sunja takes refuge in an offer from a Presbyterian minister named Isak, whom she agrees to marry and accompany to Japan to begin life anew. Despite escaping shame in her local community, in following the pastor, Sunja enters into an entirely different kind of exile — that of being a stranger. Residing in Japan during a tumultuous period in history, she faces the incumbent cultural differences, nationalism and prejudice characteristic of the turbulent years to come, while both rearing a family and finding a true friend in her sister-in-law.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS By Angie Tally

Tony, by Ed Galing

Caldecott-winning artist Erin Stead’s lovely soft illustrations bring to life this quiet, gentle poem about Tony, a beloved horse with wide, gentle eyes and a ton of love. Sure to be a treasured favorite of horse lovers young and old, Tony is a nostalgic look back at simpler days when animals and quiet hours were an integral part of everyday life. Ages 3-6.

XO, Ox: A Love Story, by Adam Rex and

Scott Campbell

Clumsy as, well, an ox, Ox finds himself absolutely silly in love with a graceful diva, Gazelle. In letter after letter, Ox declares his undying love for the uninterested Gazelle until . . . Cute and clever, XO, Ox is perfect for Valentine’s Day shelves and will bring a smile to lovelorn readers of all ages. Ages 3-6.

The Unwanteds Quests: Dragon Captives, by Lisa McMann

This is book No. 1 in the new middle-grade fantasy series sequel to the best-selling and award-winning The Unwanteds series, about kids whose creative abilities give them magical powers. Identical twins Fifer and Thisbe Stowe are naturally gifted magicians yet unable to control their amazing powers. When they enter Artime’s magical jungle, they accidentally cause chaos, leading to their possible expulsion from the realm. Called “Hunger Games meets Harry Potter,” it’s the perfect adventure series for book hounds. Ages 10-14. Lisa McMann will visit the Country Bookshop on Thursday, February 9 at 4 p.m. to read from and sign copies of her books.

Short, by Holly Goldberg Sloan

Julia is short. So short, in fact that when she is cast for a summer stock production of The Wizard of Oz, Julia is given the role of a munchkin. By the beloved author of Counting by 7s, this heartwarming and funny novel is a story of passion, kindness, self-discovery, and the importance of those special role models who change us forever. Ages 10-14. PS